IDR Blog

Why Bangladesh feared Indian invasion after 1975 coup

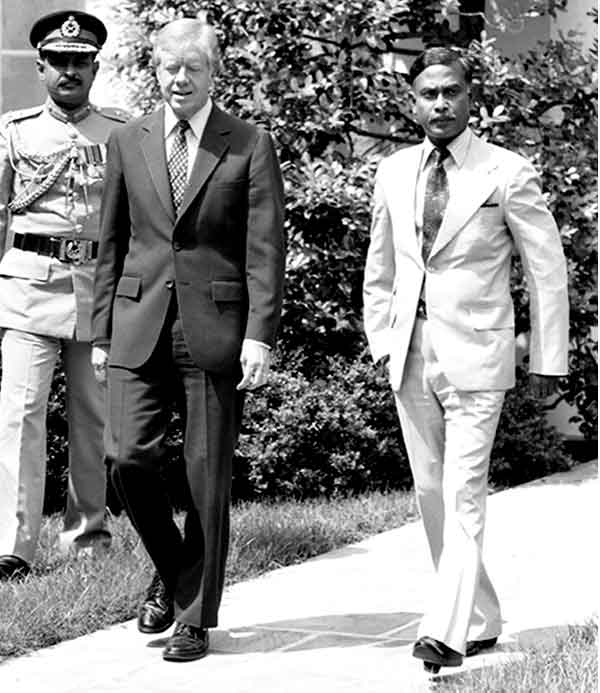

Bangladesh President Ziaur Rahman with U.S. President Jimmy Carter on the White House grounds in August 1980. On 26 November 1975, Zia told U.S envoy Irving G. Cheslaw that he feared an Indian military invasion in a few days and asked that America put pressure on India to stop this madness. India “should be made to realize that this is not 1971. This is 1975 and they will find a military force of sixty thousand and a population of seventy-five million that will present enormous problems for” for New Delhi.

When Gen. Ziaur Rahman became Bangladesh’s virtual ruler following several bloody military coups in 1975, he told the United States that India intended to invade its small neighbor to install a puppet regime.

Fearing a direct Indian intervention, the new regime instructed Nazrul Islam, acting foreign secretary of Bangladesh, to seek U.S. support to discourage New Delhi.

So intense was Zia’s fear of an Indian invasion that on 7 November 1975 he made a call on the radio for national unity to face the attack. His call triggered more processions in Dhaka, initially sparked by the news of his release from detention by the officers who had mounted a failed coup earlier. The processions were laced with anti-Indian slogans.

This public mood in Dhaka reflected a total reversal of the sentiment at the end of the Bangladesh war in 1971 when the sentiment was explicitly anti-Pakistani and secular. Following the November 1975 events, the attitude turned explicitly pro-Pakistani, pro-Islamic, pro-American and pro-West.

Fearing a direct Indian intervention, the new regime instructed Nazrul Islam, acting foreign secretary of Bangladesh, to seek U.S. support to discourage New Delhi. He was to request that America convey Bangladesh’s feelings regarding the possible Indian move to China and Pakistan so that they could mobilize support from the Muslim countries. Accordingly, Islam asked Irving G. Cheslaw, U.S. Chargé d’Affaires in Dhaka, for support to checkmate any Indian invasion.

As Islam talked with Cheslaw in Dhaka, the U.S. consul general in Kolkata discussed the events in Bangladesh with Ashok Gupta, West Bengal chief secretary, and Gen. J.F. R. Jacob, Eastern Command deputy chief, at a Soviet reception. Gupta described the Bangladesh situation as worrisome. Fighting was still going on there, and Dhaka’s air was thick with anti-Indian slogans.

Indian general predicts Zia’s peril

Jacob spent at least an hour at the reception. He was evidently in high spirits, obviously enjoying the host’s vodka. He told Consul General David Korn that the Bangladesh situation was “very bad.” He predicted Zia would not last very long.

The Bangladesh deputy high commissioner in Kolkata told O’Neill that he did not expect “outside interference,” because the current leadership in Dhaka was very reasonable and intelligent.

When Korn asked if the fighting had ended, Jacob said it was continuing. Jacob knew this from monitoring of the Bangladesh army internal network. Korn asked what Jacob was going to do. Jacob replied, with a smile, “Nothing. I don’t give a damn about Bangladesh.”

Meanwhile, U.S. Consular Officer Joseph O’Neill spoke with a senior Indian Air Force officer and a Navy officer. He found both relaxed and unconcerned. A senior police officer told him the West Bengal-Bangladesh land border remained open.

The Bangladesh deputy high commissioner in Kolkata told O’Neill that he did not expect “outside interference,” because the current leadership in Dhaka was very reasonable and intelligent. However, his deputy, in a separate conversation, told Korn he was quite worried about the possibility of an Indian military intervention.

Indeed, Bangladesh was worried.

Mahbubul Alam Chashi, principal secretary to Bangladesh President A. M. Sayem, telephoned Davis E. Boster, U.S. ambassador in Dhaka, to seek assurance from the United States with respect to any external threat.

Boster informed the State Department that “although Chashi’s formulation was vague, what he clearly had in mind was assurance from us that we would help deter India from intervening in the current situation.”

U.S. pledges support for Bangladesh

Responding to Bangladesh’s request, the State Department instructed the U.S. Embassy in Dhaka on 8 November 1975 to deliver a message pledging American support. The message said the Bangladesh government’s “requests for our support during this unsettled period have received urgent and careful attention in Washington. We support the independence of Bangladesh and want to carry on the close and cooperative relations we have had with previous governments in Dacca. We will continue to be sympathetic to Bangladesh’s needs and concerns.”

However, the United States faced “the practical question of how best to proceed in order to achieve what both our governments desire – to stabilize the present situation and avoid the possibility of outside intervention.”

To calm the situation down, America urged Bangladesh to “take immediate steps to reassure” India that Dhaka intended to pursue good relations with New Delhi and to live up to its obligations to protect the foreign community and the Hindu minority.

America was worried that any external pressure on India, particularly if it appeared to be organized by the United States, as suggested by Bangladesh, would only serve to confirm Delhi’s suspicions and might well increase the possibility of Indian intervention. However, in line with Bangladesh’s requests, Washington decided to keep in close touch with Pakistan to exchange views and to make clear America’s “support for the restoration of stability in Bangladesh free from outside interference.”

To calm the situation down, America urged Bangladesh to “take immediate steps to reassure” India that Dhaka intended to pursue good relations with New Delhi and to live up to its obligations to protect the foreign community and the Hindu minority. “In our judgment, this is the best way for the new regime to support our efforts in New Delhi to reduce the likelihood of Indian intervention.”

On 8 November, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger told the U.S. ambassador in New Delhi to meet with External Affairs Minister Y.B. Chavan or Foreign Secretary Kewal Singh to seek a high-level Indian assessment of the situation in Bangladesh and convey the message that the United States supported an independent Bangladesh.

Singh assured the American that New Delhi had no intention of interfering in Bangladesh affairs. How Bangladesh ran its government was its affair. But if its policies created problems or hurt Indian interests, then “India must express its concern.”

He believed Zia knew of India’s views.

Zia panics again

Zia panicked for the second time on the night of 23 November when he feared India was about to attack Bangladesh. At 0:30 a.m., he went on the radio appealing for the nation’s unity in “this fateful hour.”

The military regime took the threat so seriously that it sent a secret envoy to Pakistan to seek Prime Minister Z. A. Bhutto’s help to fend off the Indian attack.

The military regime took the threat so seriously that it sent a secret envoy to Pakistan to seek Prime Minister Z. A. Bhutto’s help to fend off the Indian attack.

Immediately after receiving the news from Bangladesh, on 25 November Bhutto ordered Agha Shahi, Pakistan’s foreign secretary, to ask the U.S. ambassador to see him, saying he was doing so at the prime minister’s order.

Shahi had received a message hours earlier from the Pakistani ambassador in Rangoon, who had just had a meeting with Bangladesh Ambassador K.M. Kaiser. Kaiser was in Bangkok when he received telephonic instructions from the Bangladesh president to proceed immediately to Pakistan on a secret visit as a special presidential envoy.

He was to inform Bhutto of an alarming situation that had arisen for the security and independence of Bangladesh by actions of the Indians, who had already marched in and occupied certain areas of Bangladesh, an assertion the Americans later disputed.

Pakistan was less than pleased with Kaiser’s proposed visit. The Pakistan foreign office preferred a “somewhat more reliable emissary.” Kaiser asked for Pakistani visas for himself and an assistant.

As things grew tense, India sent its foreign secretary to Moscow for consultation.

Dhaka sends secret envoy to Islamabad

Henry Byroade, the U.S. ambassador in Islamabad, questioned Shahi on the timing of the reported Indian movement into Bangladesh, and specifically whether this might relate to reports a few days ago, which mentioned trench diggings along the border inside Bangladesh, or whether this was a new event. Shahi did not know. Byroade asked if he was concerned that India might try to make something big out of such a visit. Shahi said Bhutto had carefully considered that factor in deciding to go along with Kaiser’s urgent plea to visit Pakistan.

Byroade in a cable to Washington downplayed Bangladesh’s plea. He said “Kaiser is a bit of a self-starter, who gets involved in many, many things.” Shahi described the visit as a “top secret.” Bhutto agreed to see Kaiser because he feared that if he refused and his refusal became public there would be a strong negative public reaction against him for refusing to receive an envoy of the Bangladesh president.

Meanwhile, on 26 November, Bangladesh Foreign Secretary Tabarak Husain called Irving Cheslaw, U.S. Chargé d’Affaires in Dhaka, at home at 8 p.m. for a discussion, especially with Zia on Bangladesh’s concern that India could invade Bangladesh. Husain asked Cheslaw to go at once to the presidential palace.

Husain’s meeting with Cheslaw took place after an attack on Samar Sen, India’s high commissioner in Dhaka, by some armed elements of the Jatiyo Samajtantrik Dal, a militant political group. An Indian aircraft was coming to take him back to India for medical treatment. Husain believed that the high commissioner’s departure under dramatic circumstances would only further heat up the existing situation, whereas his agreement to remain would help cool it down. Sen agreed and the Indian aircraft was turned around without landing in Dhaka.

After briefing Cheslaw of the situation, the foreign secretary called in Zia and Navy chief Admiral M.H. Khan, who wanted to pursue the discussion in greater detail. Zia described India’s possible military invasion as an attempt to create instability in Bangladesh to bring into power a government completely under New Delhi’s control.

India funded JSD?

Zia claimed that Bangladesh had evidence of military movements on the border. India also established training centers and even refugee camps in many of the same locations used in 1971. He felt that the incident at the Indian High Commission compound was no coincidence. The two men caught in connection with the incident were Jatiyo Samajtantrik Dal members. JSD had been receiving money from the Indian government – directly from the Indian High Commission in Dhaka, Zia told Cheslaw.

Zia described India’s possible military invasion as an attempt to create instability in Bangladesh to bring into power a government completely under New Delhi’s control.

He expected the Indians to move into Bangladesh very soon, even possibly in the next few days. Zia asked that America put pressure on India not to follow through with this madness. He said India “should be made to realize that this is not 1971. This is 1975 and they will find a military force of sixty thousand and a population of seventy-five million that will present enormous problems for” for New Delhi. Zia believed that the Indian military needed to control the area – Bangladesh – that stood between India’s eastern territories and the rest of the country. He inferred that the Indians believed this would be an easier move to carry out because they could hold off the Pakistanis and the Himalayan passes were snowbound.

Both Zia and Husain requested that the American envoy immediately convey their tremendous anxiety to Washington – and particularly their request that the U.S. government provide all possible assistance in making India realize that this situation must be cooled down immediately.

“Walking with me to my car, the foreign secretary said he would have no objection if I conveyed the general sense of this discussion to other missions in Dacca, such as the British, even the Australians, in hope they could also be of assistance,” Cheslaw informed Washington.

As things grew tense, India sent its foreign secretary to Moscow for consultation. On 26 November, the Soviet political counselor in New Delhi told an American diplomat that he had just heard on All India Radio that Kewal Singh, India’s foreign secretary, had been received by Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. The Soviet officer expressed some surprise at this development. Singh’s meeting with Premier Alexi Kosygin had only been arranged at the strong urging of the Indian government. The Soviet Embassy had recommended appointments with Defense Minister Andrei Grechko and Kosygin.

In Washington, the State Department did not consider Kaiser credible. It advised the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad to tell the Pakistanis that the Bangladesh situation was not exactly what Kaiser told them. Accordingly, the U.S. political counselor told Hyat Mehdi, director general for South Asia at the Pakistan Foreign Ministry, “that contrary to Kaiser’s allegation in Rangoon, we had no evidence that Indian forces have occupied any portions of Bangladesh territory.”

This is an excerpt from B.Z. Khasru’s new book, The Bangladesh Military Coup and the CIA Link, which will be published shortly by Rupa & Co. in New Delhi.

Post your Comment

11 thoughts on “Why Bangladesh feared Indian invasion after 1975 coup”

Loading Comments

Loading Comments

Zia and the Ziaites were pro-Pakistanis. Zia in fact was a Pakistani agent and for very obvius reasons he hid behind a hype of probable Indian invasion and used all his might to colour Khaled Musarrefs as pro Indian. Bangladeshis after kicking out the Yazidite Pakistanis did not want Indian domination. An invasion by India was not a popular Idea. Therefore, Zia could use a probable Indian invasion threat to his benefit.

That he was not accepted by the pro independece people of Bangladesh is evident enough from his total dependence on anti-liberation forces. The writer has conviniently forgotten the several km long procession supporting Khaled Mosarref takeover shouting Joy Bangla our clarion call of Independence.

Zia did everything from awarding benefits, posts, power, bribe and threats to perpetuate in power. He ruthlessly persecuted pro-liberation forces. It became Hell for the Freedom Fighters, Awami Leaguers and their supportes. Razakars now regained their power as they had during the liberation war. He did everything possible to turn Bangladesh into Pakistan only he could not declare Bangladesh a part of Pakistan for opposition from within his own constituency the armed forces.

To obliterate any mention of our glorious independence war Zia brought Zindabad on the pretext of its being Islamic though there is nothing Islamic about it. Likewise, he intruduced ‘Bismillah’ to hoodwink the guillible people of Bangladesh. It glaringly evident in his removing restrictions on alcohol and gambling. He removed “a historic struggle for national liberation” from the constitution and turned Historic Ramna into a park to erase all traces of history of independence as much as he could. He reversed the economy just when it fell into gear, erased historic memorabilia, documents and records and even debarred Muktijoddha and Bangabandhu from books and media. He indemnified the killers of the Father of the Nation, rehabilitated and nurtured them with a purpose to Pakistanize.

Very informative article. Unfortunately despite it’s size and strength, it’s India that is being bullied by its neighbours and not the other way.

What i feel Bangladesh should not worry from Indian side, Bangladesh has no enemy There is no need of spending $2.1 billion 2014-15.You can spend this money for your own development. India should assures his neighbor Nepal, Bhutan,Shrilanka, Bangladesh that any attack on these country will be considered as attack on India. Wasting money on Military.

Yes. But recently we noticed a wild dog as our neighbor. Mayanmar. And in this equation India is a neutral country. So we need to be ready for anything.

I think, Gen. Zia-ur-rehman himself created this paranoia to pacify his opponents and masses. He was able to subvert his population into intoxicating a nationalistic feeling in the same way Pakistan used to do and still does by invoking India and Islam. Such a propaganda was smartly designed and enacted by diplomatic offensive to confuse all stake holders. It confused military commanders who might be contemplating coup against him. External threat confused the bangladeshis who thought it better to strengthen the hands of whoever was in command. It confused India so that she did not influence any pressure on Gen Zia. Having no longer any threat from Pakistan since it was thousand miles away, it gave Gen Zia and opportunity to strengthen army and by weapons.

By the way its fashionable in south asia to demonize India as india’s foreign policy principles of Panchsheel and Gujral doctrine gives them a real long leash.

bloody stinky india

Yeah, Your last name reflects your identity, Don’t worry India is not like you stinking towelhead with blood of women and children in your hands.

Interesting report and analysis. However, you fail to discuss the context of the previous three years internally in Bangladesh, especially the Bangladesh Army’s relationship with the Indian Army post 1971. You also do not mention India’s internal political situation of the time.

You have to admit, that prior to 1975, Sheikh Mujib’s biggest propping up support externally came from Indira Gandhi’s government. In the context of his then increasing unstable leadership within Bangladesh and the subsequent coups and upheavals in Bangladesh between August and November 1975, I would think a military regime of the highly bureaucratic and paranoid type had an understandable concern over Indian interference, especially given what happened to Sikkim that very year.

This would all have been better addressed if you follow the academic line that “Democracies don’t fight each other” assuming there would be greater transparency and clarity of communication from India. Instead India itself was going through the Emergencies at the time and was similarly authoritarian at the time.

I hope the book is better referenced than this excerpt. Such articles cannot be termed any other than anecdotal and speculative without verifiable documentation of sources. It is certainly the first time I hear someone try to say that the 7th November speech regarding national unity was in anticipation of an Indian invasion. There were certainly other much more evident and compelling domestic reasons to express the same sentiments.

This is what both leeches on either side have been doing since their creation – blaming India and creating a Islamic furore in order to bail themselves out of the mess they dug themselves. Ayub Kahn, Z.A. Bhutto and their successors did it in Pakistan and Ziaur Rahman and his successors did it in Bangladesh. And all along the Congress here was busy building its own votebank.

Unfortunately if this scenario would have come up now, our esteemed MPs would have done what Bangladeshi leader did, gone begging around the world