IDR Blog

The Balance of Power of early 18th Century India

Summary

This article is the first of the two articles which concerns the balance of power in early 18th century India. The first article will discuss events preceding 1700 AD followed by the death of Aurangzeb induced chaos at Delhi. It will also detail the rise of Marathas from Sahyadri mountain ranges to making a mark at Delhi. The last section of this article will give detail of the Maratha campaign against the Portuguese and British at sea.

The second part of the article will discuss the Maratha dealings with Nizam of Hyderabad and Bajirao’s stratagem at Palkhed and Amjhera in 1728 and Dabhaoi in 1731. It will also reveal the dealings of marathas with Siddhis of Janjira including a failed attempt of 1732-33. The internal power structures and fault lines which hindered Maratha capabilities will also be discussed in the second part.

Historically BOP has been discussed in the context of Europe with very little efforts made to find the similar pattern in Indian military history. The subcontinent barring a few centuries of rule in its thousands of years of existence has remained a divided house. Hence, it is worth unravelling the military history of this ancient and sacred geography.

In the year 1700 AD, India was under the rule of the Mughals, who were led by Emperor Aurangzeb, known for his brutal tactics. The empire’s vast territory extended from Kabul to Decca (now known as Dhaka) and from Gilgit to parts of modern-day Tamil Nadu. Despite this, there was a small kingdom situated in the Sahyadri range along the Konkan coast known as Shivaji’s Swarajya, which eventually rose up to challenge the Mughals and even manipulated them at the heart of their empire in Delhi.

Nevertheless, over the course of the following two decades, events took a turn for the worse, resulting in significant territories seceding from Mughal control and turning the kingdom upside down. The genesis of this massive secession can be traced back to the death of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1707. However, it’s crucial to examine and analyse the events that led up to Aurangzeb’s demise.

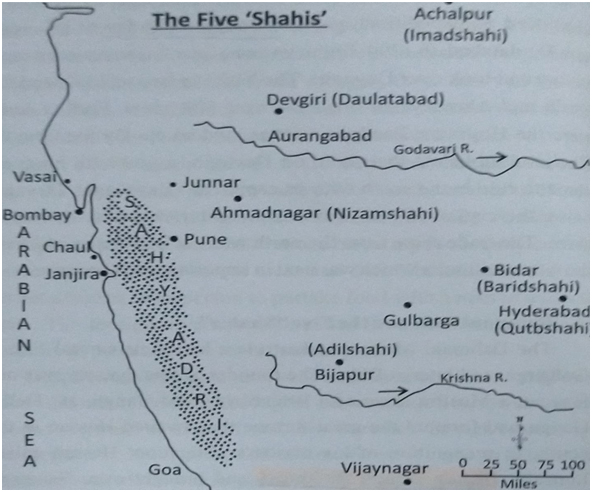

A brief introduction to the geopolitical scenario of Deccan at the end of 17th century

For a long time, the southern region of India was protected from Islamic invasions by its favourable geography. However, the floodgates were opened by Alauddin Khilji, leading to a Muslim domination of Deccan. The Bahmani Kingdom, established by Hassan Gangu Brahmani in 1347, marked the beginning of this domination. Interestingly, Hassan was a slave to a Hindu Brahmin named Gangu in Delhi, who supposedly predicted that his slave would find fortune in Southern India. When Hassan became king, he named his kingdom after his former master and remained favourable to Hindus. He even entrusted important departments like the revenue department to Deshastha Brahmins and later to Maratha Prabhus. When the Bahmani Kingdom ended in 1526, it fragmented into five Shahis in Deccan – Nizamshahi of Ahmednagar (1489-1633), Adil Shahi of Bijapur (1489-1686), Qutb Shahi of Golconda (1489-1687), Barid Shahi of Bidar (1492-1592), and Imadshahi of Berar (1484-1573). The ethnic origins of these Shahis were complex and diverse, with Adils being Turks, Berid from Georgia, Qutb from Iran, and both Nizam and Imad born as Brahmins before converting to Islam. Despite these complex ethnic compositions, a somewhat workable relationship was established between Hindus and Muslims.

[Image source: Bajirao 1: An Outstanding Cavalry General written by Col. R. D. Palsokar, M.C., published by United Service Institution of India and Merven Technologies.]

The rise and fall of the Bahmani Kingdom and the subsequent fragmentation into five Shahis, as well as the defeat of the Vijayanagar Kingdom by the Deccan Sultanates, illustrate the constant power struggles and conflicts that characterised the region during this period.

It is also notable how the Deccan sultans recruited and employed Hindus as statesmen and soldiers, despite the religious divide.

The Deccan, although, was under Mughal control but they didn’t have control on ground and as a result multiple sirdars rose up in the region. These sirdars didn’t have ideological leanings in most cases and were willing to fight for any one in return of Jagir. One such individual was Shivaji’s grandfather Maloji Bhosale, who fought for Nizam Shah of Ahmadnagar and received the Jagir of Pune and Supe areas along with control over the forts of Shivneri and Chakan. Following the death of Maloji, Shahji, father of Shivaji went ahead and claimed the Jagir. However, in 1624, the Mughals and Adil Shah attacked the Nizam Shah leading to the battle of Bhatavadi but were repulsed by the outstanding generalship of Malik Amber, the prime minister of Nizam. In the aftermath of this battle Nizam and Shahji fall out with one another leading to snatching of Shahji’s Jagir of Pune. Hence, Shahji jumped ships and joined the court of Adil Shah at Bijapur. The course of events in Deccan was moving with godspeed as after the death of Ibrahim Adil Shah, Shahji again joined the Nizam court and led a successful repulsion against the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan. Shah Jahan in 1636, bestowed Shahji his old Jagir along with a suitable position at Adil Shah’s court on the condition that that Shahji will leave the deccan. The Nizam’s were quashed around time. This also shows signs of realpolitik in Shahji’s engagement with his adversaries. In following years, Aurangzeb was appointed as the Subedar of Deccan and he built a new HQ at Khadki and named it Aurangabad. Shahji, on the other hand, left for Bangalore and quashed several Hindu rulers for the Adil Shahi Sultanate.

However, in 1642, the most trusted men of Shahji, Dadoji Konddeo, who protected young Shivaji and Jijabai when Shahji was fighting to regain his Jagir, and acted as a guru to future chattrapati, raised a battalion-equivalent infantry force along with a small cavalry for the young Shivaji. He also built Pune as headquarters of Shahji’s little kingdom. This battalion was used by Shivaji when he captured the fort of Singhgad in 16471. Konddeo recruited trusted men and paid them regular salaries, instead of giving land and vetans or hereditary rights of collecting revenue. This policy of regular salary was later mastered by Shivaji only to be liquidated by his successors who gave Jagir leading to a semi-independent Kingdom.

The internal mess of Marathas

Shivaji due to outstanding ability was able to carve out a small Kingdom for himself which he called Swarajya. However, following his death in 1680 even this small Kingdom was about to evaporate as the Mughals under Aurangzeb were hell bent on wiping out any resistance. But, first the tenure of Rajaram, who is known as the father of guerrilla tactics in Maratha military history and later of his formidable wife Tarabai, who not just kept the Kingdom intact but also strengthened its capabilities. Tarabai was an outstanding lady, as in 1700 she offered Aurangzeb a truce but he declined but her tactics of sizing fort after fort and leaving them before the onset of rain, forced Aurangzeb to seek a truce in 1707, as he failed to make any gain in Swarajya, but this time Tarabai declined.

In 1707, Aurangzeb also released Shahu from his captivity leading to a power struggle in Marathas as Tarabai, claimed that her son named as Shivaji is the legal heir to the Kingdom and on the other hand Shahu claimed the Kingdom for himself. This power struggle led to the battle of Khed in 1707, as commanders changed sides. Shahu won the battle as Tarabai was forced to leave for Kolhapur. However, the biggest gain of the battle was the future Peshwa, Balaji Vishawanath. Peshwa Balaji and later his son Bajirao, who also became Peshwa at the young age of 20 in 1720, manipulated Delhi like no one. They will install their favourables at Delhi and snatch Chath and Sardashmukhi from Mughals and Nizam of Hyderabad, which at one moment was inconceivable. The military and political achievement of the deo will far exceed that of any other Maratha.

Maratha campaign to Delhi, Rajput rulers and rise of Nizam

Delhi following the death of Auragzeb in 1707 was in an unprecedented turmoil. New kings were killed, and backchannel power brokers – Sayyad brothers- rose up. Aurangzeb was succeeded by Bahadur Shah who died in 1712 in Lahore. He was succeeded by his son Jhander Shah, who was killed in 1713 and then another ruler Farrukhsaiyer lasted till 1719. Sayyad brothers – Hussain and Abdulla – negotiated with Balaji Vishwanath, Shahu’s Peshwa and concluded in 1718 that marathas will march to Delhi and in return all territory of swarajya will be handed back to Marathas along with Khandesh, Vibarbha, Hyderabad, Gondvan and Karnataka. In return Marathas were supposed to pay Rs. Ten Lakhs every year as tribute to Mughals. These fierce Marathas imbibed with new spirit changed the rulers of Delhi as Farukhsaiyer was murdered by Sayyads and they installed a lackey Rafiuddarajah as new emperor. He too died in September 1719, now sayyads installed Roshan Akhtar a.k.a. Mohammad Shah Rangella, grandson of Bahadur shah. Marathas gained Rs. 30 lakhs along with revenue rights and lands far greater than they had controlled till then in their months-long campaign of Delhi. It is important to note here that this alliance between Sayyads and Marathas was only tactical which suited both parties, as the Marathas gained land, money and made a mark at Delhi and for sayyads the domination of Delhi was enough to seek peace. Neither side trusted each other.

The northern India was as divided as the southern part of the country with Rajputs controlling modern day Rajasthan. This region ever since the fall of Chittorgarh and olive branch of Akbar became a mughal stronghold with Rajputs working on most occasions with Mughals. Around 1700 AD, Rajputs were led by three major leaders Sawai Jai singh of Jaipur, Ajit Singh of Jodhpur and Amar Singh of Udaipur. However, Rajputs were fed up with their allegiance with the Mughals. The three leaders, in 1708, decided against marrying their daughters and serving mughals. However, Amar Singh lost to Sayyad Hussain and was forced to marry his daughter to Mohammad Shah in 1714 along with presenting Rs. 50 lakh, 50 horses, 10 elephants and jewellery worth 50 lakhs. This was a brutal humiliation induced by mughals over the warrior clans pride and thence Rajputs started to contemplate to work with the Marathas, as under the new Peshwa they were acquiring new lands and earning a lot more revenue. However, the new position offered by sayyads in the 1710s changed their minds and they continued to serve the Mughals under fresh positions as Jai singh was made subedar of Jaipur with extra land to govern, Ajit Singh was given Gujrat and Ajmer and son of Amar Singh, Abhai Singh was kept in Delhi to serve the emperor.

The political volatility in the mughal empire was huge as in deccan two battles were fought at Khandwa and Balapur in 1720 amongst subedars of mughal empire and in which the 20 years old Peshwa Bajirao also participated. These two battles propelled the rise of Chin qilich Khan, known to Indian history as Nizam of Hyderabad. At Khandwa, just south of Narmada, Sayyad stooge Dilawar Ali lost his life and at Balapur Alam Ali waged a war against Nizam, against Bajirao’s advice, and met the same fate as Dilawar. These two battles consolidated then little slice of Nizam’s empire and made him an extremely potent force which will remain at loggerheads with the Marathas.

Conflict at the sea

On the other side a new conflict was brewing. The Portuguese in the early 1700s were having a significant presence at the western coast of India with the British holding fringes. However, it was the Siddhis of Janjira who were the dominant power on the west coast. Siddhis were originally Abyssians who entered the fort – quite similar to the Acheans entry in Troy in the Trojan war – with baggage to seek refuge. These baggage were filled with armed men leading to extermination of the Koli kings who had ruled the fort of Janjira till 1490. Siddhi’s control of these vintage forts didn’t go unchallenged as initially Shivaji and later on his Peshwas tried to conquer these forts but failed in gaining the majority of the region. On multiple occasions the Marathas fought Siddhi’s, Portuguese and English, individually and combined. For Instance in 1718, English declared war on Kanhoji Angre, the Maratha naval commander, the Peshwa intervened and the Portuguese withdrew. But, then the English backed and supported by Portuguese atacked Angre in 1720 as he had captured British Ship Charlotte. This was also the time of the passing of Balaji creating void in the Maratha empire. However, the next Peshwa, Bajirao proved to be better statesmen even when compared to the high standards of his great father. Angre, on his part, is quite an ambiguous figure, he was often on loggerheads with the Marathas. On one occasion he even imprisoned Shahu’s first peshwa Bahiro Moreshwar in 1713. Later under Balaji and Bajirao, Angre and his sons became trusted partners of the Marathas. The British and Portuguese decided to capture Angre and send 65 ships in 1720 to Kulaba but Angre destroyed 52 ships destroying British will to fight2. But, the two European powers came together again in 1721 and sent 6000 armed sailors to defeat Angre. He had by then already informed the young Peshwa who personally led his troops with Pilaji Jadhav. Peshwa led troops not just defeated the combined troops but also captured European guns and ammunition.

After this battle the portuguese accepted maratha preeminence in the region. They agreed to pay chauth and Sardeshmukhi to marathas but hostilities often broke out between the two.

Conclusion

The political powers of the subcontinent during Aurangzeb’s reign barring Shivaji’s little kingdom Swarajya have accepted Mughal suzerainty. After his death his kingdom fell apart with the rise of Marathas in Deccan and in 1720s Nizam, whose ancestors were loyal servants of mughal emperors carved out a kingdom for himself. This succession was decried by mughals but they couldn’t do anything given their depleting capabilities. However, the Nizam’s Kingdom managed to ensure a balance of power in peninsular India with neither marathas having enough to comprehensively defeat Nizam nor Nizam having enough to defeat Marathas particularly when marathas were led by Peshwa Bajirao.

Before Bajirao, Peshwa Balaji Vishwanath meonovered with all factions to retrieve maximum for the Marathas. His dealings with Sayyads provided the much needed succour as Deccan was gripped with war for centuries which had impacted the farmers disproportionately leading to destitution. With a deal which brought money and land to the empire, the locals rejoiced as they could avert war and were not supposed to pay taxes to local sirdars.

A defining element of early 18th century India was that all powers depended on one another for the survival of everyone. The marathas wanted Mughals to stay as that would put check on Nizam and Nizam wanted Mughals so maratha rise can be managed, as it was mughals who till 1750s used to issue the revenue rights to both nizam and marathas. This equilibrium of power worked both ways as none would ever be able to dominate the whole geopolitical space of India and each power mostly prying upon the possible shortcomings of the other.

When such balance or equilibrium among powers existed in Europe it led to a great deal of innovations and technological development. However, in the Indian case unfortunately it wasn’t the case. Indian kings remained inward looking, similar to Napoleonic France, and acted in an ossified manner. Indians also failed to develop economic structures as the British started the bank of England in 1694 and the Indian war economy was based mostly on loot and plunder. This mistake of Indians in not investing in institutions goes on to become the biggest reason for Indian enslavement as we never had any steady source of money to continue the struggle against Islamic and British invasions. On most occasions the struggle was led by local grievances and thus failed to make a dent on the imperial powers.

The power structure in India at the turn of 18th century was monopolised by mughals but in just two decades the marathas not just eroded the mughal control but became a force to reckon with. The future military campaigns of Peshwa Bajirao, as we shall see in the next part, will further consolidate the maratha control in Deccan, Vidharbha, doab region, bundelkhand, northern India and in parts of modern day Pakistan.

Endnotes

-

Colonel R.D. Palsokar, M.C., Bajirao 1: an outstanding Cavalry General, (United Services Institution of India third edition 2020) page no. 51,52,53

-

page no. 133

Post your Comment

One thought on “The Balance of Power of early 18th Century India”

Loading Comments

Loading Comments

Beautifully written. It is a pleasure to read such a detailed piece from young! Waiting for the next part.