In 1913, war in Europe appeared imminent for the British; they finally realized that the treaties regarding Tibet signed with China (and Russia) had no relevance as they could not be implemented in practice. In these circumstances, London decided to call China and Tibet for a tripartite Convention to solve the Tibetan problem, secure a buffer zone between British India and China and ensure peace and stability in the region. Simla was selected as the venue of the Conference1 and Sir Henry McMahon2 was to chair the tripartite talks.

It was not an easy proposal; for months the Chinese were rather reluctant to sit at the negotiating table on an equal footing with the Tibetans. But diverse factors were putting pressure on them. They knew that the Dalai Lama was close to some British officers such as Charles Bell. They could fear another Lhasa Convention where they would perhaps not even be asked to participate.

In Kham, the military situation was not favourable to the Chinese as most of the territory captured by Zhao Erfeng had been recovered by the Tibetan troops. The Tibetan army was now better organised and arms and weapons were imported. After the Dalai Lama’s return, the Tibetan army was given a British type of training.

This fact worried the Chinese who were also apprehensive after Mongolia had been passed over to Russian control. Would the Tibetans join the British sphere of influence if they refused to participate in the Conference?

Hence the Chinese felt they had no alternative but to accept the British conditions and attend the Convention.

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama chose Lonchen Shatra Paljor Dorje, his old and experienced Prime Minister as his representative. He had dared to suggest negotiations with the Younghusband Mission ten years earlier. His assistant was Trimon, who had prepared detailed documentation on the legal status of Tibet, especially of the eastern border areas.

It was certainly one of the great surprises of the conference: the Tibetans had come so well prepared with volumes and volumes of original documents,3 while the Chinese had no documents to prove their allegations.

The Chinese were represented by Ivan Chen while the British Plenipotentiary, Sir Henry McMahon4 was assisted by Charles Bell, the Dalai Lama’s old acquaintance from his Darjeeling days.

The brief given to Lonchen Shatra by the Dalai Lama was clear:

- Tibet was to look after its own internal affairs;

- Her foreign affairs were to be managed for important matters in consultation with the British;

- No Chinese Amban or official should be posted in Tibet;

- Tibetan territory should include all the Tibetan-speaking areas up to Dartsedo in the east and Kokonor in the north-east.

When the Conference assembled it became immediately obvious that the positions of the Tibetan and Chinese delegates were diametrically opposite.

In his presentation, Lonchen Shatra reiterated the Dalai Lama’s points and asked for recognition of the independence of Tibet. He also wanted the Dalai Lama to be acknowledged as the temporal and spiritual leader of Tibet. He claimed that the Tibetan territory should include all the Tibetan-speaking areas of Kham and Amdo. Lonchen Shatra also requested that the Conference declare the Conventions of 1906 and 1908 invalid, as Tibet had not been a party to them. Further, an indemnity from the Chinese was claimed for the damage and destruction in Lhasa and in Kham following Zhao Erfeng’s invasion a few years earlier.

The Chinese stand was very different. Ivan Chen claimed Tibet as a part of China. He explained that due to the conquest of Genggis Khan, Tibet had become a part of the Chinese Empire. This was further confirmed when the Fifth Dalai Lama accepted some titles from the Chinese Emperor.

Another argument he used was that the Tibetans had called upon the Manchus for military assistance many times and each time the Emperor had come to provide support. He gave the examples of the invasions of the Dzungar Mongols in the 18th and the Gurkhas in the 19th century.

Regarding Zhao Erfeng, Ivan Chen explained that his government had only acted in accordance with the Treaty of 1906 and his troops were sent to protect the Trade Marts. Another ‘proof’ advanced by the Chinese Plenipotentiary to show that Tibet was part of China, was that the compensation under the Convention of 1904 had been paid by China to the British Government on behalf of the Tibetan Government.

He further claimed that the Amban had the right to have an escort of 2,600 men to control the internal and foreign affairs of Tibet. He requested that a thousand men be stationed in Lhasa and the rest in other places to be decided by the Ambans.

For the Chinese, the status of Tibet had to be restored as per the 1906 Agreement and the border between China and Tibet was to be in Gyamda, some 150 miles east of Lhasa.

The Tibetan delegate managed to counter the Chinese point by point, especially on the issue of demarcation of the territory, by tabling revenue documents.

Regarding the payment of compensation for the Younghusband expedition, the Tibetans declared that they had never asked the Chinese to pay the amount of 25 lakhs of rupees to the British and that they were not even aware of the payment.

The British Plenipotentiary was caught between two opposing viewpoints, and on behalf of His Majesty’s government, McMahon had to harmonize the two sides.

He found a way out by dividing Tibet into two parts with consequences which can still be felt today.5 McMahon thought that he could impose on both parties a ‘fair deal’ which would also have advantages for Great Britain. Tibet would be divided into two parts:

- ‘Outer Tibet’ which corresponded roughly to Central and Western Tibet including the sections skirting the Indian frontier, Lhasa, Shigatse, Chamdo; and

- ‘Inner Tibet’ including Amdo Province and part of Kham.

The arrangement was as follows: ‘Outer Tibet’ was to be recognised as autonomous. China would not interfere in the administration of Outer Tibet, nor with the selection of the Dalai Lama. No troops or Ambans would be stationed there. It would not be converted into a Chinese Province. Maps were also prepared showing the boundaries of Inner and Outer Tibet. In the interest of settling the dispute, Lonchen Shatra reluctantly agreed to McMahon’s proposal. This was in February 1914.

The Indo-Tibetan Border: the McMahon Line

But then the Chinese delegate started delaying tactics. This gave the opportunity and the time to the Tibetan and the British delegates to discuss their own borders. The object of the talks was India’s North-eastern areas, between what the British called the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA) and Tibet.

The Chinese were not invited to discuss the question of the border between India and Tibet and their acceptance of the McMahon Line was never sought; nor did they ask anything about the final demarcation. At the same time, it was not a ‘secret’ negotiation as alleged by the Chinese today.

Through an exchange of notes between the British and Tibetan Plenipotentiaries, the Indo-Tibet frontier was fixed in March 1914. It is worthwhile to quote these letters that would have important consequences for the future of both nations, especially India which, 48 years later, would fight a war along the McMahon Line.

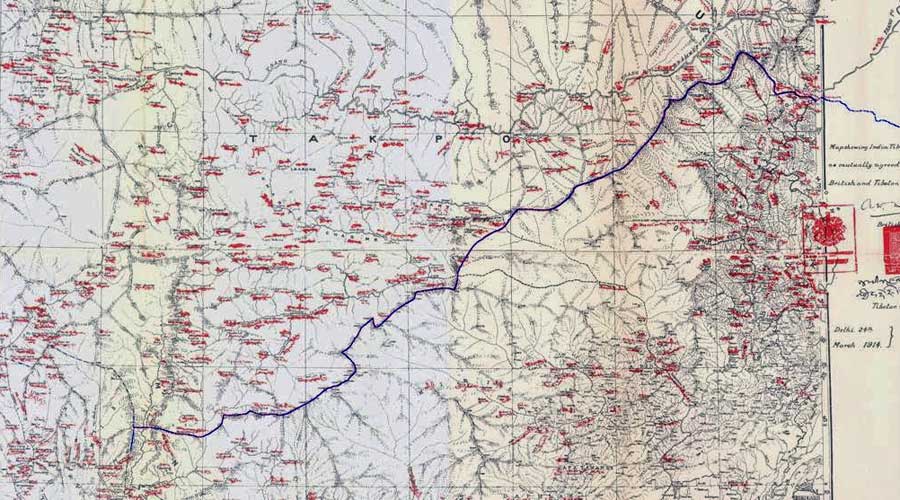

The British Plenipotentiary wrote to Lonchen Shatra on March 24 attaching a rough map (1 inch for 8 miles).

In the first letter dated 24 March 1914, McMahon writes:

To Lonchen Shatra, Tibetan Plenipotentiary,

In February last you accepted the India-Tibet frontier from the Isu Razi Pass to the Bhutan frontier, as given in the map6 (two sheets), of which two copies are herewith attached, subject to the confirmation of your government and the following conditions:

- The Tibetan ownership in private estates on the British side of the frontier will not be disturbed.

- The sacred places of Tso Karpo and Tsari Sarpa fall within a day’s march of the British side of the frontier, they will be included in Tibetan territory and the frontier modified accordingly.7

I understand that your Government has now agreed to this frontier subject to the above two conditions. I shall be glad to learn definitely from you that this is the case.

You wished to know whether certain dues now collected by the Tibetan Government at Tsona Jong (Dzong) and in Kongbu and Kham from the Monpas and Lopas for articles sold may still be collected. Mr. Bell has informed you that such details will be settled in a friendly spirit, when you have furnished him the further information, which you have promised.

The final settlement of this India-Tibet frontier will help to prevent causes of future dispute and thus cannot fail to be of great advantage to both Governments.8

The main problem is it was never demarcated( delineated) on the ground, so the …….

The point is chinese dilly dallying and india ignoring the threat and surrendering when it was feasible to bargain.

We seem to forget that the old adage which alluded to possession being accounted for as three fifth’s of the law. The rest is all verbiage! Throw the illegal occupants out if you can or keep quiet and carry on with your photo op protests till the cows come home. As Indians, we were then colonial subordinates to the British- they did what ever suited the English interest. We slumbered through 1947 & till 01 October 1949 when the PRC was formed. We may now say that we were in the throes of our partition pangs and foreign affairs was the least of the then Government’s concerns. What prevented us from resolving the issue to our advantage in the 50s when the PRC was still consolidating?. It went nuclear only in 1964. Our military incompetence gave us a bloody nose in 1962 for the world to see. Now we trot out all manner of insinuations marshalling what we feel are arguments that prove our point when the facts are otherwise.China grabbed Tibet in the 50s when it was not very strong in a military sense- they had just wrought a stand still on the Western borders along Yalu river before they pushed further further SW to the 38th parallel and could use battle hardened veterans against a nimby pamby pest to their East to annex Tibet. Negotiations or talks won’t get us back what we have lost. There is a lot of pragmatism & real speak in diplomacy. We have yet to learn that.