It had to happen – the political and military absurdity that was East Pakistan was never a viable proposition. No country made of two halves so geographically separated and culturally alienated like Pakistan was, could possibly survive as one entity, no matter what the religious sentiments dictated. Britain’s last Viceroy of India had predicted it to last, at best, a quarter of a century; the events overtook the prediction by a year. But what turned out to be pathetic was that Pakistan, headed by Yahya Khan’s military junta, messed up things so very badly, that in the end the matter was settled under such humiliating circumstances for that country. They just refused to see the writing on the wall; and instead of granting the Bengalis their legitimate democratic rights, went on to crush the aspirations of an entire people in the most ruthless manner possible. A revolution was inevitable.

By any reckoning, given the magnitude of influx of refugees into the country, India had no other option but go to war, notwithstanding the fact that there was nothing better India would have liked to see than Pakistan truncated as it happened due to the war. It was an unprecedented victory for Indian arms, one which has been hailed by military experts the world over as one of the most successful operations ever conducted after the Second World War. Over 90,000 officers and men of Pakistan’s armed forces surrendered unconditionally to the Indian Army at the end of the war. A new country, Bangladesh, was created. An achievement of that magnitude couldn’t have been possible but for India’s bold and sensible political leadership, complemented by a brilliant military strategy. The Pakistani junta’s arrogance and stupidity came as a bonus, with a shamefully defeatist attitude of the country’s armed forces in its eastern wing.

India, which started off being a sympathetic party to the Bengali cause, soon found itself covertly involved in training Mukti Bahini, the army of their freedom fighters, and was to finally go in for an all out invasion of East Pakistan. The success of the operations owed a lot to the fact that the Chief of Army Staff refused to be browbeaten to take hasty or unwise steps, and conducted the war in the time and manner as dictated by sound professional reasoning (at the time of the year when the weather and ground conditions were favourable, and after the army had had adequate time for planning and preparations). And the Pakistani establishment naively missed out on the one chance it had to avert the catastrophe – it failed to preempt the war, and force India to take the field before she was ready and under unfavourable conditions for an offensive.

Thus to start with, India had all the advantages. But then advantages alone do not add up to such a total and decisive victory. Pakistan still could have salvaged its reputation, by smartly exploiting the one inherent advantage it had – the riverine terrain of Bengal. There are few better defender-friendly terrains anywhere in the subcontinent. And India did not have the 2:1 superiority in numbers, conventionally required for an offensive to succeed. A determined and well-organized defence could have slowed down the Indian offensive and made the victory far more costly, probably offering Pakistan the bargaining power for a face saving formula. But the Pakistani army in the east had long ceased to be a professional force. The indulgence of the officer corps had abysmally eroded the morale of the men. And in the end when it came to the fighting, excepting for odd instances, most of their army just put up a token resistance for the first few days, and then fled even when they had a fighting chance. Demoralized and feeling betrayed by their own government, their only concern was to get to Dacca somehow from where they hoped to be extricated, from what they perceived to be the trap that East Pakistan had become, with the Indian Navy blockading its ports and the Indian Army formations closing in on them from every direction. (Even then, they lost over 2000 killed and some 4000 wounded in the operations, not counting an equal number of casualties they suffered during the build-up to the war since March that year.)

In contrast, the morale of the Indian troops, ready and raring to go, was on an all time high. Ultimately it was their dash and determination that reaped the glory. 1500 of them perished doing that, and another 4000 were wounded. That toll could have been far lesser and the victory far speedier, had it not been for the unfortunate – and the inherent – timidity of some of our commanders at unit as well as formation levels, who remained bogged down with their archaic textbook notions of warfare, while they should have used their imagination to unleash the younger men on a blazing blitzkrieg that the operation should have been. In fact, that was how it had been planned – brilliantly so – by the Eastern Command. And our air force had ensured – by knocking out whatever air power Pakistan had in the east within the first few hours of fighting – that the army could advance with absolutely no hindrance from the air. Yet we were often found vacillating, obsessed with an exaggerated perception of enemy strength. Our advance on many instances was held up by ‘enemy strongpoints’, which ridiculously enough, when ‘attacked and captured’ contained no enemy at all. And when it came to genuinely strong positions held by the enemy, more often than not, we went for blunt frontal assaults with disastrous results, instead of smart outflanking manoeuvres that would have threatened their rear. The lessons from the war of ’65 did not seem to have sunk in on many of the field commanders.

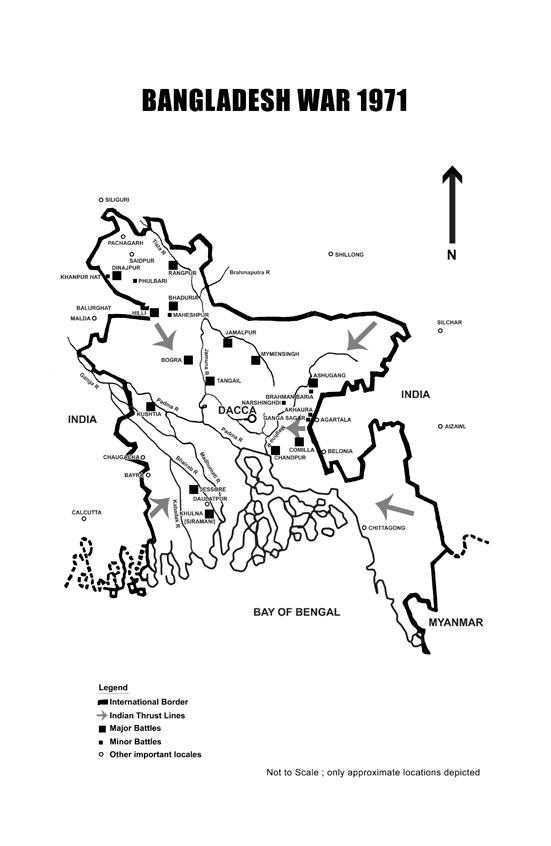

The credit for the grant victory thus must primarily go to the indefatigable fighting spirit of the officers and men in general, and the sound strategy employed by the Eastern Command. Codenamed ‘Operation Cactus Lily’, the grand plan envisaged an invasion of East Pakistan simultaneously from four directions in a swift, enveloping move. The newly raised 2 Corps made up of two infantry divisions was to move in from the Southwest; the Siliguri-based 33 Corps with two divisions and some additional brigades was to move in from the Northwest; and the Tripura-based 4 Corps with three divisions was to advance from the Southeast, while an ad hoc formation under command the Shillong-based HQ 101 Communication Zone Area, with a brigade group that was to be supplemented by a brigade or two and a parachute battalion, was to move in from the Northeast and eventually head for Dacca.

Although a full-fledged war commenced only on 3 December, sparked off by the preemptive air strikes by Pakistan in the Western Sector that afternoon, in the East the Indian troops had occupied enemy territory up to 10 kilometres across the border during November itself, in preparation for the offensive. The main operation that followed was conducted generally according to the plan. A 3-pronged advance by 2 Corps from the Southwest swarmed the entire part of East Pakistan which fell south and southwest of the river Padma (Meghna, downriver), by investing Khulna down south, and pushing eastward up to Faridpur by the banks of Meghna and northward up to Kushtia and beyond to the Hardinge Bridge on the river. Similarly a pincer movement by 33 Corps from the Northwest invested Dinajpur and Rangpur in the north, and eventually converged to capture Bogra to the south, overwhelming the enemy in the whole area that side bound to the east and south by the two rivers, Jamuna and Padma. 4 Corps, moving in from the Southeast, invested Sylhet to the north, and captured Ashugang and Chandpur, before effecting a crossing over the Meghna, to threaten Dacca. The Corps also dispatched a subsidiary force to invest the port town of Chittagong far south. Meanwhile the ad hoc force under 101 Communication Zone Area invested Mymensingh and Jamalpur in a pincer move from the Northeast, and converging further south, para dropped a battalion ahead in Tangail area and raced forward to hit the outskirts of Dacca, which, more than anything else, drove home the point to Pakistan’s Eastern Army Command that surrender was their only option.

The historic surrender, by Lieutenant General Amir Abdul Khan Niazi, Martial Law Administrator Zone B and the Commander Eastern Command (PAKISTAN), to Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora, General Officer Commanding in Chief, Indian and BANGLA DESH forces in the Eastern Theatre, took place at 16311 hours IST on 16 December 1971, at the Dacca Race Course. East Pakistan was no more, and Bangladesh was born. The Indian soldiers had made it happen; but as it is their lot always, no monument in the new nation-state commemorates their role in it.

The Indian Army’s moment of glory was deservedly shared by the Madras Regiment and the MEG, who both played their roles to the hilt in the operations. Three battalions of the Madras Regiment, 4, 8, and 26, took the field, all of them with formations which moved in from the West Bengal border.

4 Madras, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel SL Malhotra, which formed part of 340 Mountain Brigade under 20 Mountain Division of 33 Corps (Northwestern Sector), went into action as early as 12 November, and was one of the first units to be engaged. They began with the capture of a Pak border outpost, Khanpur Hat, some 12 miles south of Dinajpur, in a preemptive move to secure a bridgehead for the eventual advance of the brigade. The attack, mounted before dawn on the 13th after moving up during the night, turned out to be a nasty bit of action, with the enemy – a couple of platoons and some Razakars well-fortified with quite a few machineguns – holding out rather stubbornly. The battalion had gone in two companies short, but supplemented by a company of BSF and two companies of Mukti Bahini, the last more or less dissolving once under fire. Artillery and tank support were at hand, but with the war yet to be declared, couldn’t be brought to bear. In the end a blistering assault by the battalion took the objective by daybreak. In less than two hours the enemy launched a counterattack supported by tanks, only to be beaten back by a spirited defence, aided this time by artillery and mortar fire. The bridgehead had been established. At least 12 dead bodies of the enemy were counted after the battle.

The brief engagement saw exceptional acts of gallantry by the officers and men of the battalion. Naib Subedar PO Cherian, the JCO Adjutant of the battalion, was knocked down by a machinegun burst 40 yards from the objective. He pulled himself up, and bleeding but undeterred, led his men in the charge until the objective was taken. He was awarded the Vir Chakra. During the counterattack, the Commander of the Recoilless Gun Detachment, Naik LR Joseph, was shot up by tank fire. Severely wounded but with great presence of mind he popped off two rounds in quick succession and managed to relocate the gun, before permitting himself to be evacuated.

The actual war was still three weeks away, and the battalion meanwhile went on to expand its hold on to some 26 square kilometres of the enemy territory; a factor which was to prove of immense tactical benefit when the operations commenced on 3 December. This often called for small-scale but sharp engagements. In a gallant piece of action, a single platoon commanded by Second Lieutenant Bandyopadyay overran the Ghughudanga Bridge over Gouripur Canal. The officer was decorated with a Sena Medal; so was his leading Section Commander, Lance Naik Chinnathambi, the latter posthumously. The NCO had silenced a Light Machine Gun which was holding up the advance by crawling right up to it, falling prey to the enemy fire in the act.

Once the operation commenced, the far-flung forward companies began to come under enemy attacks. On 6 December, D Company under Major Phul Singh withstood and fought off an exceptionally powerful attack supported by tanks. Subedar Perumal of the company was killed trying to take on the tanks with a rocket launcher. Major Phul Singh himself was wounded and taken prisoner with three of his men when the enemy overran a portion of the company position; but the company held out. (In an interesting turn of events, the major and his three men were to be liberated from the enemy by men of 4 Madras themselves on 16 December, after the battle of Bogra wherein the battalion partook.)

While 4 Madras kept the enemy so engaged, the rest of the brigade began moving south, isolating Dinajpur for good. With the enemy resistance fading in a couple of days the battalion was also on the move to catch up with the brigade, which had traversed 100-odd kilometres southeastward by then. Meanwhile a stalemate had developed at Hilli to the south, where 202 Mountain Brigade had launched an abortive attack on 22 November. On 10 December the Divisional Headquarters assigned a special mission to 4 Madras, to capture an enemy strongpoint to the rear of Hilli so as to threaten its defences. It turned out to be a brilliant piece of tactics, and is best chronicled by the man who conceived it and had it executed, Major General Lachhman Singh Lehl, GOC 20 Infantry Division. The General wrote in his book on the war, Indian Sword strikes in East Pakistan:

I ordered 4 MADRAS to move from Dinajpur area to Nawabganj and placed them under 66 Mountain Brigade……..At this stage, Malhotra, an energetic and bold Commanding Officer, reported to me. His battalion had arrived in Nawabganj area in the afternoon. I ordered him to capture Maheshpur on 10 December and destroy enemy guns and Brigade Headquarters in the area. This operation would have automatically threatened Hilli from the area. I had information that the enemy had one artillery battery, one Infantry Company and Tajjamul’s Brigade Headquarters in the area. I placed 63 Cavalry less two squadrons under Malhotra, and Subha Rao arranged artillery support for him from guns deployed in Nawabganj area. Malhotra moved cross country during night and surprised the enemy in Maheshpur. The tanks shot up a number of vehicles and destroyed two enemy guns and captured another two. There was panic in the enemy Headquarters where they started burning documents as they were afraid our tanks would overrun their Headquarters. However, our tanks did not know about the exact location and were content to capture enemy guns and shooting up vehicles. The raid created chaos in the enemy’s rear and Brigade Headquarters and denied artillery support to the defenders of Bhaduria in the subsequent battle. (‘Tajjamul’ referred here is Brigadier Tajjamul Hussain, the Commander of Pakistan’s 205 Brigade which was defending the area.)

and not one word about Tibetans army from Special Frontier Force (SFF) or 22 establishment who fought gallantly but all credits under Mukti Bahni.