On the other hand, IAF first fought an independent war of counter-air action of its own, and later one of deep interdiction, but these did not influence the course of the land battles. IAF ground support for decision-making land battles was marginal and did not in any way affect their outcome. For example, in the crucial battle of Khemkaran, despite frantic demands from the formation pitted against Pakistan’s No 1 Armoured Division, not more than four to six sorties materialized although daily promises of massive support were made.

When queried, the usual answer was that because of higher priority the effort had been diverted to the Sialkot sector. On comparing notes after the war, it was discovered, much to the Army’s dismay, that a similar reply was given about the same time to the formations engaged in the Sialkot sector, namely that because of pressing tactical necessity the effort had been diverted to the Khemkaran sector. Such was the state of affairs in the higher direction of war as regards coordination of effort.

In our ground preparations, the southern sector was inade- quately covered by the airfield complex. As a result, no air support could be provided in the Rajasthan and Kutch sectors. Further, about a third of the available aircraft were committed against East Pakistan, knowing fully well that no action was envisaged in that region. It was ridiculous not to utilise the inherent characteristic of flexibility in aircraft to switch them from one sector to another to fit the tactical requirement of the time. It was argued that the maintenance facilities organised at air bases by type of aircraft did not make such swift switching over possible from one airfield to another. Surely this was due to bankruptcy of advance planning on the part of IAF.PAF had on the other hand organized itself well. By systematic establishment of air bases with satellite airfields and rear dispersal areas, and by organisation of duplicate maintenance facilities, it had endowed itself with flexibility and freedom of operations by a combination of options to meet both known and unforeseen contingencies. The early warning radar installations painstakingly organised to cover the entire border, with overlaps, enabled the detection of the Indian aircraft from the take off stage onwards. This gave the Pakistanis enough reaction time to dispose of their own aircraft and arrange interception. The Indian radar cover had wide gaps, and since the radars installed had mainly a high-looking capability the Pakistani pilots avoided detection by flying sorties at treetop level. They had perfected the art of low flying by day and night with precision, and much training must have gone into achieving this proficiency.

Also read: The Air Force in War-I

Indian pilots copied these tactics in the conflict itself, but proficiency took long to achieve. Arjan Singh had failed to foresee the need for such evasive tactics, and as such the Indian pilots were ill prepared to counter Pakistan’s air tactics in combat. The Pakistani Air Force, having foreseen the requirements and significance of decisions in land battles, had devoted great attention to developing procedures and techniques involved in demanding and hastening air response, recognising targets and their effective engagement, and had achieved a very high standard of proficiency and accuracy in this respect.

Click to buy: India’s wars since independence

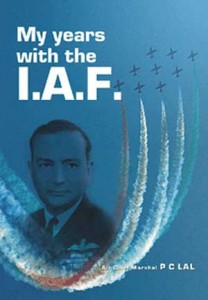

The Indian Air Force on the other hand was still paying lip service to close air support by following outmoded Second World War procedures and techniques when the jet age had overtaken the slow-speed piston aircraft for which these procedures had been evolved. Modern jet aircraft following the old techniques could not even take on ground targets. As a result IAF made very little contribution to the outcome of land battles. This prompted a Khemkaran battle veteran to remark to Air Chief Marshal PC Lal, when he took over from Arjan Singh: “Sir, you are taking over the highest-decorated air force in the world. But [it] did nothing to help the ground battle and we, the soldiers, are bitter about it. Let us hope under your stewardship amends are made and in the next conflict we do get some help.”

The performance of the units operating in Jammu and Kashmir was praiseworthy and won undying admiration from soldiers and senior officers alike.

In 1956 the Indian Government had concluded an agreement with Follands, a British aircraft manufacturing firm, to produce the Gnat under licence in India, and by mid-1959 this midget lightweight fighter aircraft was cleared for service. By the time war came in 1965 IAF had three frontline Gnat squadrons in service. The Gnat was at the time capable of outclimbing, out-turning and out-accelerating contemporary transonic-class fighters in South Asia. The Gnat squadrons were the mainstay of our air defence. They covered our air bases against sneak raids and also escorted Hunters and Mysteres on deep missions over Pakistani territory.

This diminutive fighter got to be popularly known as the “Sabre slayer”, for with its superior manoeuvrability it proved capable of outfighting both Sabre and Starfighter in combat. It was particularly effective at low altitudes, where its ability to manoeuvre enabled it to evade Sidewinder missiles. Because of its small size Pakistani pilots found it difficult to detect and follow in air action.

Indian pilots fared well, and where there was a matching chance in air combat they were not found wanting. They were however let down, firstly by the higher direction of the air war. IAF seemed to be fighting its own independent war. Its activities contributed only marginally to the course of the 1965 conflict. Secondly, committing obsolescent aircraft like the Toofani and Mystere in battle against superior performance aircraft like the American Sabre and Starfighter did not give the Indians an equal chance in air combat. The attrition rate was naturally high, and perforce the Air Force had to be liberal in dishing out awards to keep pilots in the air. Worst of all, the higher command failed to anticipate the requirements of a short war and evolve new concepts to suit Indian needs. For this Arjan Singh must squarely take blame as he was at the helm of affairs for almost six years before the conflict.

Although no official evaluation of IAF’s performance was made at the end of the conflict, its lessons were well imbibed by Lal. Well known for his managerial expertize, he set out with rare zeal to redress the shortfalls in basic concepts, infrastructure and organisational spheres. He changed the concept of the basic role of the service. Visualizing the need for optimum use of combat resources in arriving at decisions, he gave priority to the direct support of ground battle and insisted that re-equipping,, training and operational employment should be oriented towards this goal.He found that Air Headquarters itself as well as its command setup was organized on the Second World War pattern. Besides being top-heavy, the force functioned in watertight compartments and showed little concern for cost effectiveness. Lal proposed a complete overhaul of the organisation, and with his personality and sound arguments got the Government to accept his proposals. Broadly, the reorganisation reflected an emphasis on policy planning, while systems analysis introduced a progressive long-term outlook to keep the force in comparative combat trim. The days of hand-to-mouth existence were over.

Also read: Parameters for Indian Army 2020

In the field of logistics Ial reorganized the supplies and repair and maintenance organisation on a weapon-system basis so that the pipeline was not clogged by the intermeshing of conflicting requirements. In the operational field he insisted on speedier development of detection and communication systems so as to quicken the response to hostile action. An infrastructure of new airfields closer to the border and attendant servicing facilities were painstakingly created as a planned growth.

In training, the procedures and techniques for demanding air support for army formations and directing modern jet aircraft to targets was revised to cut down response time, and periodical exercises were undertaken in conjunction with the Army to perfect them further. Above all, Lal insisted on the immediate replacement of the obsolete inventory of Vampires, Toofanis and Mysteres and brought in more sophisticated aircraft. Although he was not able to achieve his planned goal, at the start of the Indo-Pak conflict in 1971, IAF had a definite superiority over PAF.

In 1971, India had 45 squadrons in all of combat and transport aircraft against Pakistan’s 13, compared with 34 and 12 respectively in 1965. The Vampire, Toofani and Mystere had been replaced by the Russian-built SU-7 to a large extent, and the 11 squadrons equipped with these aircraft had been reduced to only two. MIG-21 squadrons had simultaneously gone up from one to eight. PAF had acquired 90 Chinese MIG-19s, but their performance. was far inferior to the MIG-21, by then part manufactured in India. The MIG-21 could hold its own against Pakistan’s Starfighter, but it was no match for the recently acquired Mirage, of which Pakistan had about 24 by then.2

Notes:

- Asian Recorder, Vol I, p. 501.

- Asian Recorder, Vol XVIII, No 1, “Strength of Pakistani Air Force,” p. 10537.

The Mirage was superior in all respects including speed, sophisticated weapons system and manoeuvrability. Both sides were weak in deep-penetration bombing capability, but were near parity in bomber strength. India’s radar detection system, earlier interrupted by the US withdrawal of aid as a result of the 1965 conflict, was expanded with equipment acquired from other sources, and had considerably improved its effectiveness in the western sector by 1971 although some gaps existed in mountainous areas. The voids in low-looking fields were made up by raising an observer corps whose members, deployed close to the border, immediately reported whenever they saw or heard a plane passing overhead. Communications for speedy passage of this information were based on VHF wireless sets and by patching existing telegraph circuits.

Click to buy: India’s wars since independence

Pakistan had a good detection system in 1965, and India strove to improve its own through skilful employment of a combination of radar and observers. This detection system was completed just before the start of hostilities. It was an improvisation, but nonetheless an effective substitute for the more sophisticated electronic system under procurement according to a longterm plan. Air bases had been created in Kutch and Rajasthan so as to provide overlapping coverage of the entire western front to a great extent. Well camouflaged concrete pens had been provided for dispersing aircraft at forward airfields as a protection against a pre-emptive strike.

There was however a wide gap in the eastern theatre, where there was only one air base at Kumbhigram in the area east of East Pakistan. Fighters operating from this airfield could not adequately cover the Chittagong sea coast in the south. There was a civil airfield at Agartala which could be activated for military use if required, but because of its proximity to the East Pakistan border it was under machine gun and artillery fire and was therefore unusable till some territory in depth could be secured to eliminate this threat. An effort was made to construct another airfield on the Karimganj-Agartala road about 20 miles inside Indian territory in Tripura, but the project was conceived much too late to fructify in time. Responsibility for the uncovered southeastern coastline was accordingly taken over by the air arm of the Indian Navy.The division of air operational responsibility was rationalized. Western Air Command, with headquarters at Palam, was to be responsible for air defence and tactical air support for the entire western theatre, Eastern Air Command, with headquarters at Shillong, for the eastern theatre, and Central Air Command, with headquarters at Allahabad, for deep strategic bombing in its entirety and maritime reconnaissance. For close liaison and joint planning with the Army, Advance Air Command Headquarters were established with the Army’s Western and Eastern Commands at Simla and Calcutta respectively. Each corps and independent division headquarters was provided with a Tactical Air Centre Organisation so that close air support could be integrated in planning and day-to-day conduct of ground operations.Replacement and re-equipment would perhaps have proceeded in a leisurely fashion but for the start of US aid to Pakistan the same year.

A combined team of the Air Force and Army officers was positioned with formations down to brigades for control of and guidance to aircraft on targets. Signal communications were established for speedy and exclusive transmission of air support demands from the unit in contact with the Air Force wings allotted in support of land battles. Procedures for demand, screening and execution of a mission were streamlined and rehearsed during training so that when war came they were in a state of near perfection.

Lal fully appreciated the basic characteristic of flexibility in the air arm and felt that this could be fully exploited by switching aircraft at will from one task to another, and similarly from a dormant sector to more threatened areas, with ease. This necessitated interceptors, ground support, fighter and fighter-bomber aircraft functioning as composite teams, helping each other to achieve the ultimate aim in combat. It was common to see a mixture of Gnat, Hunter, MIG-21, SU-7 and Marut aircraft at forward bases. Aircraft like the Mystere, of comparatively poor performance value, were relegated to areas where the air situation was more favourable.

This aircraft mix created complex problems of maintenance and other service backing in the way of armament and so on, but these were solved under Lal’s able guidance. As a result, any combination of aircraft could be switched from one theatre to another, and within a theatre from one sector to another, and could function from any air base without upsetting the infrastructure or the pipeline. This endowed IAF with tremendous capability, which was exploited to the full.

Also read: IAF: The strategic force of choice

In addition, being a super-manager himself, Lal strove to make the optimum use of the available aircraft by harnessing any machine on the Air Force inventory which was airworthy. All training establishments were closed and trainer aircraft, along with instructors, functioned as combat units. In the event even Harvards, Vampires, Toofanis and Hunter trainers did their bit in war. There was some initial resistance to the use of mixes from ground engineers and operational men, but this was overcome by the persuasive Air Chief with patience and tact. He inspected each Air Force base personally to find an answer to the problems encountered with practical suggestions. To his credit, by the time war came every pilot and airman had developed full confidence in the concept.

On the eve of the Chinese invasion in 1962 IAF constituted the largest and most effective air power in the region.

The Chinese invasion in 1962 resulted in rethinking on air defence, both tactical and strategic. It was accordingly decided to divide the responsibility for air defence by ground weaponry against attacks at high and low levels. The responsibility for defence below 5,000 feet remained with the Army, while the Air Force took over the responsibility for dealing with aircraft and missiles flying above that level.

Although negotiations were conducted with Britain on the purchase of Bloodhound SAMs, the final choice fell on the Russian V-75 SAM system. A few of these were acquired and installed around vulnerable points before the 1965 conflict but their meagre number and lack of proper integration with other weaponry left wide gaps in the air umbrella. The mainstay of low-level defence was the anti-aircraft L-60 Bofor gun of the Second World War. It depended on visual engagement by day and sought to trap flying aircraft in an extensive barrage at night. Manually operated, it had difficulty in tracking supersonic aircraft, especially at low altitudes. Although many claims, like that of Subedar Kunju, were made of downing Pakistan Sabres the hits must have been scored more by accident than design. At best the weaponry India possessed in this field could only act as a deterrent.

Chinese policies in the Himalayas, the growing menace of insurgency and civil wars in Southeast Asia, and even more the acquisition of supersonic Starfighters by Pakistan, sent India in frantic search for similar aircraft for IAF.

Having learnt a lesson, India set about overhauling its air defence organisation. To replace the outdated L-60, some L-70s were procured and arrangements made for its indigenous production. The L-70 was radar-controlled and could track aircraft effectively both by day and night. The replacement programme was well underway, and by the start of the 1971 conflict the bulk of the sensitive areas had the protection of the new gun against low-level attack. On the whole, a workable integration had been achieved between the detection system, the Air Force SAMs and air defence guns both in the tactical and strategic zones.

On the other hand, the Pakistani Air Force which took to the skies in 1971 was totally different from that of 1965. It could field a total of 250 frontline aircraft, and these were organised into about eleven and a half squadrons comprising F-86 Sabres, a few F-104 Starfighters received under US military aid, some Chinese MIG-19s, Mirages, B-56 bombers and T-33 jet trainers. One squadron was deployed in East Pakistan and the remainder in the western wing. After September 1965 the US had stopped the supply of spares, and as a result Pakistan had to keep its fleet of American-built aircraft in the air by obtaining spares from third countries. In this regard Iran, Jordan and Turkey proved of great help, to the extent that they even loaned fully assembled aircraft to tide over Pakistan’s difficulties in war.

This polygon collection of weapons systems, representing technologies of both the East and the West, had its attendant logistic problems, especially the sluggish flow of spares. The worst affliction however was the defection of some personnel of Fast Pakistan origin early in April 1971 which led to grounding the remaining airmen from that province. It embraced about 25 pilots and, worse still, 25 per cent of the ground technicians. This seriously affected the serviceability of aircraft and the war potential of PAF.

Even more serious was the crisis in leadership of the force. Air Marshal Nur Khan, who had painstakingly raised it to new heights of efficiency in 1965, was finding it difficult to get along with the power-intoxicated Yahya Khan. Nur Khan was eased out of office with the bait of governorship of a province to make room for a more pliable air chief. Air Marshal Abdul Rahim Khan, who succeeded him, lacked the daring and foresight of his predecessor and did not inspire confidence among the younger pilots. All this and much more air intelligence gathered through defectors was used very effectively by IAF as the drama unfolded.It appears from the PAF deployment in East Pakistan that they had already given up the struggle before war came to Bangladesh. Apart from army aviation flights of MI-4 helicopters Abdul Rahim Khan had some 16 F-86 Sabres operating from two airfields in Dacca. Although East Pakistan had a network of civilian and military airfields covering the entire province, none of the other airfields was activated, and this deprived the operating air force of the inherent flexibility of dispersal and forward fighting at the very outset.

Click to buy: India’s wars since independence

The observer group, which had been earlier deployed on the periphery of the border for early warning, had to be withdrawn in view of the activities of the Mukti Bahini. It was impossible for isolated parties like this group to sustain themselves in hostile surroundings. The mainstay of early warning having been eliminated, the low-looking radar at Dacca was also dismantled and moved to West Pakistan to cover higher-priority gaps.

IAFs growth was so haphazard that by October 1962 it possessed an extraordinary mix of aircraft, some 30-odd types of British, American, Canadian, French, Russian and Indian manufacture, with their attendant problems, especially of logistics.

The lone Sabre squadron was not only blind but had no place to go to in case it was hunted down in its lair, and was facing far superior Indian air strength operating from all directions. The fatigue of sustained counterinsurgency operations from April 1971 and the feeling of isolation and prospects of an unequal fight was having its effect both on men and machines. IAF had some six to eight squadrons of Hunters, MIG-21s and Gnats pitted against the Pakistani loner.

The first skirmish between the two forces took place in the East on 22 November,1 when Sabres attacking the Indian positions opposite Boyra, in the Jessore sector, were intercepted by Gnats at a low level. In the ensuing dogfight two Sabres were shot down, and maybe a third, with the possible loss of one Gnat Pakistan claimed. On the outbreak of open war in the eastern theatre, the first offensive raid was carried out by MIG-21s against Tejgaon and Kurmitola air bases near Dacca. In ceaseless attacks for the next two days, both by day and night, these airfields were rendered non-operational by heavy cratering of the runways and complete disruption of maintenance facilities.

In the 20 odd attacks by MIGs on this complex, three inter-cepting Sabres were shot down over Dacca. The Pakistanis claimed to have destroyed nine Indian aircraft. Whatever the count in aircraft casualties, IAF established complete mastery of the East Pakistan skies within 48 hours of war.2 Whatever remained of the Pakistani squadron was grounded, and was later destroyed on the ground by the Pakistanis themselves as part of their scorched-earth policy. Simultaneously, Chittagong airfield was raided by Hunters approaching the target over the sea in to-hi profile. The airfield was bombed, installations strafed and some ships anchored in the harbour sunk, but the gain in military terms was small because the airfield was not in use. This action however brought credit to the Indian Navy’s Seahawks operating from the aircraft carrier Vikrant.

Enjoying freedom of the skies, IAF operated with impunity, except for occasional groundfire, and supported the Army’s blitzkrieg by relentless attacks on the Pakistani fortresses and other strongpoints. In addition, it completely disrupted all movement along roads and waterways serving Pakistani forward formations. According to Niazi and his formation commanders, the movement of troops and vehicles had become impossible in daylight. The fast-advancing Indian columns received supply drops, ammunition and POL when surface means of transport could not keep up with the Indian thrust lines.Apart from this close conventional air support to the land forces, IAF made a significant contribution by certain innovative actions which altered the course of the war in Bangladesh and are therefore worth highlighting. The first was the use of 12 MI- 4 helicopters for airhopping troops, guns and equipment over the formidable river obstacle Meghna in support of the IV Corps race to Dacca. On the night of 9/10 December these helicopters lifted 1,270 men, nine guns and 40 tons of material across the river from Brahmanbaria to Raipur. On the next two days and nights they lifted the bulk of 57 Mountain Division’s leading brigade comprising 2,791 men and 3,200 kilograms of equipment and stores in the same region, thus earning the appellation Air Bridge. It proved that, given bigger helicopters, possibly fitted with armament, heliborne capability could add new dimensions to land and air warfare in the way of flexibility of employment with enhanced mobility across natural and artificial barriers.

Enjoying freedom of the skies, IAF operated with impunity, except for occasional groundfire, and supported the Army’s blitzkrieg by relentless attacks on the Pakistani fortresses and other strongpoints. In addition, it completely disrupted all movement along roads and waterways serving Pakistani forward formations. According to Niazi and his formation commanders, the movement of troops and vehicles had become impossible in daylight. The fast-advancing Indian columns received supply drops, ammunition and POL when surface means of transport could not keep up with the Indian thrust lines.Apart from this close conventional air support to the land forces, IAF made a significant contribution by certain innovative actions which altered the course of the war in Bangladesh and are therefore worth highlighting. The first was the use of 12 MI- 4 helicopters for airhopping troops, guns and equipment over the formidable river obstacle Meghna in support of the IV Corps race to Dacca. On the night of 9/10 December these helicopters lifted 1,270 men, nine guns and 40 tons of material across the river from Brahmanbaria to Raipur. On the next two days and nights they lifted the bulk of 57 Mountain Division’s leading brigade comprising 2,791 men and 3,200 kilograms of equipment and stores in the same region, thus earning the appellation Air Bridge. It proved that, given bigger helicopters, possibly fitted with armament, heliborne capability could add new dimensions to land and air warfare in the way of flexibility of employment with enhanced mobility across natural and artificial barriers.

Also read: India’s quest for Anti-Ballistic Missile Defence

The next was the raid on Government House, Dacca, where, as a signal intercept revealed, a historic cabinet meeting was to be convened to decide the course of the war. Within an hour or so of the interception of the message by Indian intelligence six MIG-21s were airborne,3 and with only a tourist map of Dacca as a guide they made such an accurate rocket attack on the meeting room that the shaken Governor scribbled his resignation in great haste. A similiar precision attack on Pakistani troops holed up on Dacca University campus for a last ditch stand followed. The quick response and the precision of the attack indicated the skill of the pilots and the power of the weaponry IAF wielded in battle, and this still remains to be fully exploited.

Bureaucratic failure to produce timely and accurate lists of spares and the strange behaviour of the Government, which spent freely on buying aircraft but displayed miserliness in providing spares, brought about a sharp decline in the serviceability curve of our frontline aircraft.

PAF started the war in the western theatre late on the afternoon of 3 December with air strikes on the Indian forward air-fields at Pathankot, Amritsar, Srinagar and Avantipur. More raids followed late at night under a full moon on airfields covering the entire Air Force complexes along the border- Amritsar, Halwara, Ambala, Pathankot, Sirsa, Jodhpur, Uttarlai, Jamnagar and Srinagar. For a pre-emptive this was a rather tame affair, for at no time did Pakistan employ more than a total force of 18 to 26 aircraft for the task, and this meant only two to four aircraft raiding a particular airfield at a time. With this much effort the main aim of the Pakistani attack seemed to be to diminish IAF capability to operate from its forward bases, thereby forcing it back to its rear fields and thus decreasing the range of penetration into Pakistani territory. The main methods of attack were 750-pound bombs on runways and strafing and rocketing radar installations.

These attacks damaged some airfields, but the damage was small. With the repair organisation set up at each airfield, IAF was able to effect repairs with modern materials like quick’ setting cement in a matter of hours. The runways were fully serviceable throughout the war. Anticipating such an attack on the part of Pakistan, the Air Force dispersed its planes among rnany airfields and kept them well protected in concrete pens. As a result not a single Indian plane was destroyed on the ground in these strikes.

IAF took four to six hours to retaliate. There was much adverse comment about this delay in reaction in the Indian press the next day. Some apologists then advanced the theory that this was meant to tire Pakistani interceptors flying patrol over their air bases and expecting instant Indian retaliation. This lame excuse did not hold water as interceptors get airborne on receiving warning of an approaching raid, and there was no question of a modern air force constantly patrolling air bases, especially in rear areas, when the reaction time was adequate to be airborne before it materialised.

The real reason was that in anticipation of a pre-emptive attack IAF had dispersed its aircraft among rear bases outside the range of the Pakistani F-84 and F-104. It took some time to collect and group them before launching a counter-offensive. The first raid on the Pakistani air bases took place about 2300 hours on 3 December. The Indian Canberras struck at the air bases at Chander, Sargodha, Mianwali, Rafiqui, Murid and Risalwala. Early next day about 200 sorties were flown by Hunters and SU-7s against these bases and the radar installations at Sakesar and Badin. Later in the day Hunters penetrated as deep as Kohat, Peshawar and Chaklala. These attacks continued on 5 December as well with renewed vigour.

Also read: The Madhesis of Nepal

Raids by Hunters and SU-7s flying low were invariably escorted by MIG-21s at a higher level. This not only facilitated swooping on the Pakistani interceptors from positions ofadvant- age but was also a line of sight for the VHF relay link between low-flying raiders and their control stations at forward bases. Coded Sparrow, these MIG-21 standing patrols were later declared Russian-manned TU-20 AWACS (airborne warning and control system) aircraft by Pakistani evaluators. Nothing was farther from the truth.

The two-day onslaught on the Pakistani air bases was meant to cause crushing attrition by destroying aircraft on the ground and damaging runways, radar and attendant maintenance facilities to cripple the airworthiness of PAF. The ordnance used varied from 400-pound blockbusters to anti-tyre steel tripods. Some of these bombs were supposed to penetrate deep into concrete before exploding, thus causing irretrievable damage to runways. The Indian press published claims of 30-odd Pakistani aircraft destroyed in the counteroffensive, out of which five or six transports were destroyed at Chaklala and one at Mianwali. In addition, fuel dumps at Karachi and Attock were destroyed. The vital radar centre at Sakesar was damaged and remained unserviceable throughout the war, thus creating a gap in the early warning system which India exploited in subsequent air operations.

Notes:

- Asian Recorder, Vol VVII, No 51, “Three Pakistani Jets Shot Down,” p. 10511.

- Ibid., pp. 10538-10539.

- Asian Recorder, Vol XVIII, No 3, pp. 10562-10563.

Pakistan claimed the destruction of three Canberras and 17 other aircraft in air combat and by ground fire from the anti- aircraft guns of the heavily defended Pakistani air bases. Irrespective of claims and counterclaims, it may be said that IAF found this type of counteroffensive costlier in attrition, and the results achieved were certainly not commensurate with the effort involved. PAF interceptors operated in home air space with a slight edge over raiding Indian aircraft. But this offensive was of immense value indirectly to the conduct of the war in that PAF got so involved in defensive operations that it was unable to support the Pakistani Navy when it was under attack both from sea and air in and around Karachi. It also saw the total disruption of Pakistan 18 Division’s offensive in the Rajasthan Desert by a couple of Hunters operating in Pakistani skies without fear of interference.

Click to buy: India’s wars since independence

Lal soon grasped the futility of pursuing the counteroffensive and switched over to the strategy of interdiction, embracing the destruction of lines of communication and industrial targets affecting the immediate land battle. These targets were systematically tackled all along the front. In the north a detachment of four Vampire trainers, besides bombing Skardu airfield, disrupted narrow valley roads leading to Kargil, Tithwal, Lipa, Uri and Poonch in addition to destroying dumps providing logistic support to these fronts. The railway system connecting Karachi- Lahore-Rawalpindi was ceaselessly pounded in the Sialkot and Lahore sectors to prevent any significant military movement. Railway sidings and marshalling yards housing what looked like oil tankers and installations were rocketed and straffed.

In the later stages of the war no train could ply on this route unless covered by continuous air patrols. Burning trains, damaged locomotives and marshalling yards in shambles were a common sight. The strike on the Attock oil refinery, resulting in a “beautiful blaze,” combined with destruction of the oil instal- lations at Keamari and elsewhere on the west coast, almost dried up the oil backing of the Pakistani Army. But the most significant contribution of IAF in this regard was frustrating. Tikka Khan’s offensive in the Ganganagar sector with Pakistan Strike Force South, comprising 1 Armoured Division and an infantry division.Fearful of the deployment of such a thrust line towards Bhatinda, Manekshaw had asked for surveillance of the area opposite. On such a mission four Mysteres operating from Nal and Sirsa forward airfields to take photographs were destroyed by anti-aircraft fire from innocent-looking sand dunes. Taking a tip from this Pakistani reaction, IAF flew about 300 missions against expected launching areas for the offensive in Pakpattan,. Fort Abbas, Haveli, Mandi Sadiq Ganj and Bahawalnagar. According to some defecting Bengali officers from 1 Armoured Division, IAF destroyed the divisional petrol dump at Chistian Mandi, the power house in Bahawalpur, 27 tanks loaded on a train, five guns and 13 vehicles. This damage in itself could not amount to very much, but what was significant was the damage to bridges and other crossings over the Sutlej and the canals. south of it.The entire resources of Indian Airlines were employed along with the IAF transport fleet to fly formations from the plains of Punjab and elsewhere to Tezpur, Gauhati and Dibrugarh to reinforce NEFA, and to Bagdogra for induction in Sikkim.

This retarded the force’s buildup for the offensive for 48 hours or so, by which time developments in the Rajasthan sector forced the Pakistan higher command to split 33 Infantry Division and divert two brigades north and south towards 1 Corps and 18 Infantry Division respectively. This depletion of the infantry component of the strike force nullified Tikka,. Khan’s offensive for good. The offensive, scheduled to start on. 7 December or so, was postponed because of the slow buildup and was later scuttled because Pakistan’s higher command panicked. IAF undoubtedly helped in frustrating Pakistan’s counteroffensive, which might have altered the course of the war-in the west.

PAF did not usually interfere with these interdiction missions. The reasons for this are many and have been enumerated earlier. The Pakistanis generally got to know of the raids, only after the intruders had gone across the border. Moreover, the shorter range of interdiction did not allow PAF enough reaction time for interception, especially when operating from rear areas in depth. Another reason Mugeem gives in defence of the operational pilots is that Pakistan’s Air Chief had so centralized control that for mounting a single mission permission had to be obtained from the Chief himself. This cramped the style of the local commanders and hampered flexibility in the use of air power. As a result IAF had complete freedom of the skies in the forward Pakistan communication zone, while PAF continued to dominate its own air bases, and neither side later interfered with each other’s spheres, to the great advantage of India.

Before Pakistan could redress its shortfalls in strategy and deployment the fortunes of war had been made and unmade. The losses suffered by the Pakistani Navy in the way of shipping and tanks by 18 Infantry Division at Longenwala were directly attributed to PAF inability to intervene because of faulty and timid handling. Nevertheless, PAF did attempt close interdiction on the western front. It went for the ammunition dumps at Akhnur and Ferozepur, but without much effect. The halfhearted attempts at Bhatinda, Gurdaspur, Mukerian and Barmer railway stations caused some damage, but more to civilian traffic. An ammunition train was however destroyed at Mukerian.

Also read: Anti-India mindset entrenched in Pakistan

On the other hand, IAF was very much in evidence in direct support of land operations, and its significant contribution to some of them needs to be highlighted. When the Poonch sector was under heavy attack and its fate was for a while in the balance, IAF was asked to attack the Pakistani gun areas and rear administrative installations. As these were outside the range of fighters, Canberras and modified AN-12s were mustered to execute the task. Night bombing of the Kahuta area, south of Haji Pir Pass, was carried out on a large scale.

“¦IAF had no serious training in tactical support of land battles in the rugged and mountainous terrain of NEFA and Sikkim.

According to prisoners who were interrogated as well as authentic reports from a defector, our carpet bombing generated a great deal of noise without causing much damage to the Pakistani organisations. The guns had been deployed close to the ceasefire line on the reverse slopes of high hills, and the logistic dumps were well protected by the hills. As a result, bombing did not materially alter the course of the battle, but all the same it was heartening to see the Air Force come to the aid of the Army in rugged hilly terrain, and with a big bang.

The Indian Army was caught unawares by the Pakistani offensive in the Chhamb sector. Pressing home the advantage of surprise achieved, the Pakistanis captured Chhamb town on 6 December. The next day they secured the line of Manawar Wali Tawi, and efforts were afoot to pursue the withdrawing 10 Infantry Division across the river. PAF, despite its preoccupation with Indian air attacks on its bases, was providing intimate support to the advancing troops with an average 30 to 40 sorties a day. In this period IAF was conspicuous by its absence.

“¦primarily oriented to meet the Chinese threat, the exercise indirectly brought out the weaknesses against Pakistan as well.

The army was told that it had been diverted to achieve freedom of operation in the tactical area by knocking out Pakistan’s forward airfields in accordance with the overall plans of the Air Force. Till then the ground support effort could only be marginal and the Army should be content with this. Army Headquarters protested and got the Air Force employment reversed at the instance of Manekshaw. Lal ordered all efforts to be concentrated in the Chhamb sector to help the Army recover its positions. On the night of 7 December Pakistan had established a bridgehead across the Manawar Wali Tawi and managed to induct some armour into it.

On the morning of 8 December IAF joined the battle, flying 200 sorties. With Hunters, SU-7s and Canberras it struck with rockets by day and bombs at night at Pakistani tanks, guns, vehicles and troop concentrations. These attacks were kept up on the same scale for two days, claiming the destruction of 60 tanks and 20 guns. The success of the Army counter-attack on the night of 9 December was attributed mainly to the destruction caused by the air attack across the river in the Pakistani rear areas. The Pakistani decision to withdraw from east of the river, as indicated in Muqeem’s book, was due to the accidential death of the general in command and the pressing need to divert troops from this sector elsewhere.

Whatever the reason, this amply demonstrated the inherent flexibility of the Air Force and its ability to concentrate efforts wherever required in a tactical area and set the pattern for its future use. Similarly, in the Hussainiwala and Fazilka sectors the Air Force helped prevent Pakistan from taking advantage of local setbacks. The question is not what was achieved, which is indeed creditable, but how the Indian advance to Rahim Yar Khan was planned on the support of a meagre force of four Hunters stationed at Jaisalmer, out of which two were unserviceable. What would have happened if the Pakistani Air Force, operating from the nearby airfield at Jacohabad, had decided to support the armoured thrust on a large scale. The fate of the battle in reverse was made possible more by bankruptcy of joint planning at the level of the Pakistani higher command than good planning on the part of IAF.Operating from Uttarlai in the Thar Desert, Maruts supported 11 Infantry Division’s advance towards Nayachor. The border post Ghazi on the way to Khokhrapar was attacked with rockets which softened the way for the advancing troops to the extent that it was taken without a fight. The advancing columns reached the outer Nayachor defences over the trackless desert virtually without opposition. Since the construction of vehicle tracks had not caught up with the advancing troops the help of the Air Force was sought to drop drinking water, food and ammunition. IAF refused, saying that at that range Maruts could not provide adequate escort for unarmed transports. Even at night it did not take a chance, fearful of Pakistani inter- ference. Nor could it stop daily forays by Pakistani aircraft on trains transporting much-needed water and other supplies. The Maruts found it hard to operate without MIG-21 cover although in the later stages of the war they did claim one F-86 over Nayachor.

Click to buy: India’s wars since independence

The air operations in support of the naval action in and around Karachi were well executed both in terms of synchronisation and effectiveness of strikes, and unqualified success was thus achieved against the Pakistan Navy. For this IAF deserves all credit.In the sphere of trar sport support a battalion group was paradropped at Tangail in Bangladesh, and an infantry brigade group was later flown out from Bagdogra to reinforce the Fazilka sector. This was in addition to routine maintenance of the posts in Ladakh and NEFA facing the Chinese.IAF’s performance in 1971 was a remarkable improvement on its showing in 1965, mainly because the emphasis this time in applying air power shifted from a private air war to supporting land and sea battles where decisions were at stake. Moreover, the direct participation of the force in crucial battles in-close cooperation with the Army and Navy made its contribu- 4ion more visible. Frustration of Pakistan’s Cbhamb offensive, disruption of Tikka Khan’s planned thrusts towards Bhatinda, destruction of Pakistani armour at Longenwala, and the raids on installations in Karachi port in conjuction with the Navy were notable contributions to ending the short war on favourable terms for India. The credit for this must go to Air Chief Marshal PC Lal for the overall conduct of operations and to the gallant air units which executed his plan with verve and daring.

After much debate, the Government accepted a target of 45 operational squadrons, thus making IAF the fifth largest standing air force in the world.

At the same time it is prudent to evaluate the shortfalls in the performance of the Air Force and find remedial measures for preparation in the next conflict, whenever it comes. IAF claimed that some 7,300 sorties were flown in both fronts in the 14-day war, averaging more than 500 sorties a day. Superficially, this appeared an effort of significant magnitude in the sub-continent in the era after the Second World War. But in fact it was not. Considering that India fielded some 38 frontline squadrons, this daily average works out at less than one sortie per aircraft per day although each squadron was fully subscribed for authorised aircraft and personnel. With efficient management this average could have easily been trebled without undue strain on men and machines. The Israelis are known to have averag- ed eight to ten sorties per aircraft per day in the earlier Sinai campaigns. Such optimum utilisation should be aimed at, but the mere increase in air effort will not be of much use if it is not advantageous in decision-making tactical battles.

The favoured status IAF enjoys has created the erroneous impression in the minds of those running this service that it is independent. They tend to forget that it is essentially a supporting service. It cannot win or lose a war on its own. Its contribution lies in supporting land and sea battles where the real decisive actions take place. Its support may be direct and tangible, in the form of close support for land sea actions, or indirect in terms of creating a favourable air situation or disrupting the adversary’s build-up by interdiction, and the transportation of men and material. Since gains on land and sea have to be taken over physically, the Air Force can do no more than support the agencies waging war in these spheres.

On 6 September, when full-fledged fighting began on the western front, Air Marshal Arjan Singh concentrated on destroying the PAF air bases, mounting facilities and aircraft canght on the ground and in the air. He employed mainly Hunter Canberras for the purpose.

This is unfortunately not understood at the higher levels of command. In an informal gathering after the last conflict, an Air Marshal responsible for the conduct of operations in the west made it appear as if IAF had singlehandedly won the war. When a responsible Army officer respectfully pointed out that the Air Force had played only a supporting role, which however it had played well, the Air Marshal lost his shirt. He threatened to report him to the Army Chief for actions amounting to spoiling interservice relations and warned him that in the next conflict the Air Marshal would see that whichever formation the Army officer commanded would be starved of air support.

This was a typical instance of the fact that IAF had become a highly personalized service. The Air Marshal felt that in allotting air support he was bestowing a personal favour, and this was more evident in the allocation of communication or reconnaissance helicopter sorties at all levels. This led quite unnecessarily to friction in working arrangements among the services, Although IAF is a separate service, allotment of effort, assigning priorities and their efficient application should remain a joint service decision if optimum utilisation of the effort is to be achieved.

The existing system and procedures for close air support were devised in the Second World War and basically related to handling a piston-driven, slow-speed aircraft with old-style radio and line communications functioning between units demanding support to Air Force wings executing a mission through intermediate formation headquarters. Classical close air support applies. to targets in contact with forward troops, where a groundbased forward air controller (FAC) can direct aircraft to the target under his observation.

In plain country the zone of observation does not usually extend beyond 3,000 to 4,000 yards. In such terrain supporting artillery and other ground weaponry can be brought to bear much more speedily than air support. From statistics of the 1971 war the time-lag between demand and actual execution varied from one to one and a half hours. This is operationally unacceptable, especially when dealing with mobile targets like tanks or those temporarily stationary, as within this time they would have either caused damage or moved away because of ground fire.

Despite his (Arjan Singh) claim at the end of the war that he had destroyed nearly half of Pakistans air fleet, he failed to achieve freedom of the Pakistani skies and was unable to prevent Pakistani raids on sensitive Indian areas up to the last day of war.

Acquisition of targets by high-speed jetcraft presents a serious problem. Jets find it difficult to pick up a stationary target and have to be directed by FAC, at times by smoke indication. This however may be difficult if artillery is in action in the area at the same time. With the ever-increasing speed of modern aircraft and improved methods of target concealment and defence it is becoming exceedingly difficult to pinpoint ground targets in the tactical area from the air.

This problem becomes more pronounced when adversaries face each other from well-camouflaged fortifications. These factors have rendered air-delivery weapons less effective and have resulted in a higher attrition rate of ground-attack aircraft. Neither the efforts of a skilled FAC, ground-based or airborne, nor highly sophisticated sensors from infra-red to the “people sniffer” introduced in Vietnam have helped overcome this difficulty, and our susceptibility to this limitation is steadily increasing.

There is a case for using comparatively slow aircraft in ground attack. These aircraft should have greater endurance and ordnance carrying capability than present-day jetfighters. They should be specially designed for this task on the lines of the A-10 developed by the USAF-for ground attack purposes. For us this would mean having a separate high-speed aircraft for defence and long-range interdiction and slower aircraft for ground attack, especially for targets close to the positions of our troops. Even armed helicopters could be used in such a role, reinforced with protective armour against small arms fire. Incidentally, introduction of helicopters in this role might well result in bringing close support to ground troops deployed in mountains within the realm of possibility.

Both in defensive and offensive operations the requirement of close air support in the tactical area pertains to opportunity targets in close contact and under observation of forward troops. These targets are invariably within the capability of ground weapons and warrant air engagement only where greater and more effective weight of fire is required. This type of engagement uses only a fraction of the total availability of close air support effort. Since short wars are sustained from forward dumps, an effective way of utilizing the-air effort would be interdiction at a short and intermediate range.Short-range interdiction visualizes the isolation of battle zones so as to disrupt movement between the administrative areas of the formation in contact and the forward troops and thus prevent the movement of reinforcements and reserves into the battle area. If effectively carried out, it should affect the war potential of the forward troops adversely within 24 hours.Similarly, isolation of battlefield at greater depth amounts to intermediate-range interdiction and should be effective within 48 to 72 hours. In the context of a short war it would be more pro- fitable to carry out short and intermediate interdiction by close air support rather than dissipate the effort in winning the air war and in long-range interdiction tasks which do not materially influence the course of the war.

Click to buy: India’s wars since independence

The existing procedures sub-allot the available effort in the form of a number of sorties to field formations at corps level. Inadvertently, the present system of suballotment of air effort and the tendency of formations to make demands from each sector fritters away the inherent air force flexibility of concentration and its capability of switching quickly from one target to another. This effort remains dispersed at present, though there is a definite need to concentrate on sensitive areas based on tactical priorities at the cost of squeezing dormant sectors.

In 1971, India had 45 squadrons in all of combat and transport aircraft against Pakistans 13, compared with 34 and 12 respectively in 1965.

The projected concept visualizes the air effort to be concentrated at a chosen point, and such concentration shifts from one area to another, depending on the tactical demands of the, time. Close interdiction and engagement of targets near forward troops are undertaken by armed helicopters and slowmoving, fixed-wing aircraft while faster jetplanes carry out intermediate interdiction and provide air cover to slow ground-support air- craft. The system calling for air support should enable a response within ten to 15 minutes. This would be possible as slower aircraft and helicopters would operate from advance landing strips and helipads located near the battle front.

High-endurance aircraft can also maintain an airborne alert. The army should not get bogged down with enormous logistic support in terms of fuel and armament loads, servicing facilities and repair organisation if air operations from two landing strips are to be carried out. There will be more disadvantages than gains.

Also read: Military Power: The Task Ahead

IAF has reached the optimum level of 45 squadrons the country can afford to sustain at least for some time to come. The aim should therefore be to increase war potential within the force level rather than seek expansion. Improvements sought should be in weaponry, delivery systems, concepts, response formulations and crisis management. The basic consideration in our concepts should be to serve the immediate requirements of a short war rather than systematically destroy the adversary’s war potential to get an edge over him in a protracted war.

The Mirage was superior in all respects including speed, sophisticated weapons system and manoeuvrability.

This focuses attention on the requirements of the immediate battle zone. Winning a favourable situation over our air space and that of the tactical area should receive priority over all other air operations. This environment would allow interdiction, both short and intermediate, and close support in the classical form to be provided without interference, and would prevent the adversary from operating against our forward troops. This situation would also enable us to use our air and heliborne strike forces with added three-dimensional involvement capability.

The prime consideration should be to sharpen the teeth of the air arm within the force level. This can be easily achieved by, firstly, shedding certain roles which rightfully belong to other services and, secondly, by discarding the obsolete inventory, which has only a marginal use in the present context. The decision to hand. over the role of maritime reconnaissance to the Navy is therefore a progressive step and should be carried forward by giving heliborne tasks to the Army.

Also read: Space: the emerging battleground

An Army aviation corps may be created, as in most foreign armies, for this purpose out of the nucleus of Army pilots already handling air observation post helicopters. The medium transport Packet fleet, no longer required for airborne tasks in view of its replacement by an equivalent helilift, should be discarded. The saving thus accruing in crew and ground personnel may be used to increase the teeth element.

Pakistan had a good detection system in 1965, and India strove to improve its own through skilful employment of a combination of radar and observers.

As for the future Air Force inventory, there is need, as has been stressed earlier, for a close support aircraft slow in speed but highly lethal in weaponry. Thus a low-cost and relatively unsophisticated aircraft may have to be developed for this role. In addition, the development of the existing helicopter fleet with the capability of firing cannon, rockets and air-to-ground missiles is indicated. To win the air war and for deep interdiction very sophisticated, high-speed, multipurpose aircrafts are necessary.

The MIG-21 is the standard interceptor, and has also been employed in a strike role with limited weapon loads. The improved version under production is expected to have a greater range and payload. It is likely to fill the role of multi-purpose combat aircraft and may replace the Hunter and the Gnat as and when they are phased out. An Indian advanced-strike aircraft is expected to be inducted in the 1980s, but from the experience of the Marut this may prove a futile exercise. So India should look round for a suitable replacement, especially in view of the projected acquisition of better performance aircraft of the Phantom class from the US and the Mirage-F1 and the Jaguar from Western Europe.

For long-range interdiction the Canberra will need to be re-placed by a better version of a bomber in this decade. It may be seen that by shedding some roles legitimately belonging to the other services and by a rational equipping policy IAF can increase its punch considerably. Any increase in force level as a trade off of an equivalent decrease in the other services, as advocated by some armchair strategists, is not warranted. There is however further room to increase its output efficiency by sustaining more sorties per day through good management. The trail PC Lal blazed must be pursued with vigour.

There are shortfalls in the location of forward airfields where the depth of offensive thrusts is limited by the range of fighter cover operating from them. It is therefore essential to construct new airfields closer to the border to meet the present dimensions of thrusts by both armies. But in the future, when mobility is restored on the battlefield by superior generalship and equipment and deeper thrusts are possible, it will be necessary to capture enemy airfields and rehabilitate them speedily to support our operations where possible or devise some method of laying temporary airfields quickly. Failing either, there is scope for using vertical take off aircraft of the Harrier class. IAF had better learn to look for this capability for use in the next war.

In air defence, better integration, possibly computerized, between the early warning systems and communication networks connecting AD weaponry and air bases, especially in the tactical area, is indicated, and existing gaps need to be expeditiously closed.