On the other hand, IAF first fought an independent war of counter-air action of its own, and later one of deep interdiction, but these did not influence the course of the land battles. IAF ground support for decision-making land battles was marginal and did not in any way affect their outcome. For example, in the crucial battle of Khemkaran, despite frantic demands from the formation pitted against Pakistan’s No 1 Armoured Division, not more than four to six sorties materialized although daily promises of massive support were made.

When queried, the usual answer was that because of higher priority the effort had been diverted to the Sialkot sector. On comparing notes after the war, it was discovered, much to the Army’s dismay, that a similar reply was given about the same time to the formations engaged in the Sialkot sector, namely that because of pressing tactical necessity the effort had been diverted to the Khemkaran sector. Such was the state of affairs in the higher direction of war as regards coordination of effort.

In our ground preparations, the southern sector was inade- quately covered by the airfield complex. As a result, no air support could be provided in the Rajasthan and Kutch sectors. Further, about a third of the available aircraft were committed against East Pakistan, knowing fully well that no action was envisaged in that region. It was ridiculous not to utilise the inherent characteristic of flexibility in aircraft to switch them from one sector to another to fit the tactical requirement of the time. It was argued that the maintenance facilities organised at air bases by type of aircraft did not make such swift switching over possible from one airfield to another. Surely this was due to bankruptcy of advance planning on the part of IAF.PAF had on the other hand organized itself well. By systematic establishment of air bases with satellite airfields and rear dispersal areas, and by organisation of duplicate maintenance facilities, it had endowed itself with flexibility and freedom of operations by a combination of options to meet both known and unforeseen contingencies. The early warning radar installations painstakingly organised to cover the entire border, with overlaps, enabled the detection of the Indian aircraft from the take off stage onwards. This gave the Pakistanis enough reaction time to dispose of their own aircraft and arrange interception. The Indian radar cover had wide gaps, and since the radars installed had mainly a high-looking capability the Pakistani pilots avoided detection by flying sorties at treetop level. They had perfected the art of low flying by day and night with precision, and much training must have gone into achieving this proficiency.

Also read: The Air Force in War-I

Indian pilots copied these tactics in the conflict itself, but proficiency took long to achieve. Arjan Singh had failed to foresee the need for such evasive tactics, and as such the Indian pilots were ill prepared to counter Pakistan’s air tactics in combat. The Pakistani Air Force, having foreseen the requirements and significance of decisions in land battles, had devoted great attention to developing procedures and techniques involved in demanding and hastening air response, recognising targets and their effective engagement, and had achieved a very high standard of proficiency and accuracy in this respect.

Click to buy: India’s wars since independence

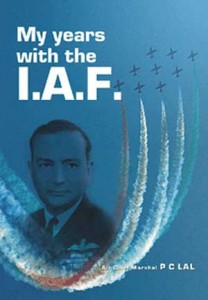

The Indian Air Force on the other hand was still paying lip service to close air support by following outmoded Second World War procedures and techniques when the jet age had overtaken the slow-speed piston aircraft for which these procedures had been evolved. Modern jet aircraft following the old techniques could not even take on ground targets. As a result IAF made very little contribution to the outcome of land battles. This prompted a Khemkaran battle veteran to remark to Air Chief Marshal PC Lal, when he took over from Arjan Singh: “Sir, you are taking over the highest-decorated air force in the world. But [it] did nothing to help the ground battle and we, the soldiers, are bitter about it. Let us hope under your stewardship amends are made and in the next conflict we do get some help.”

The performance of the units operating in Jammu and Kashmir was praiseworthy and won undying admiration from soldiers and senior officers alike.

In 1956 the Indian Government had concluded an agreement with Follands, a British aircraft manufacturing firm, to produce the Gnat under licence in India, and by mid-1959 this midget lightweight fighter aircraft was cleared for service. By the time war came in 1965 IAF had three frontline Gnat squadrons in service. The Gnat was at the time capable of outclimbing, out-turning and out-accelerating contemporary transonic-class fighters in South Asia. The Gnat squadrons were the mainstay of our air defence. They covered our air bases against sneak raids and also escorted Hunters and Mysteres on deep missions over Pakistani territory.

This diminutive fighter got to be popularly known as the “Sabre slayer”, for with its superior manoeuvrability it proved capable of outfighting both Sabre and Starfighter in combat. It was particularly effective at low altitudes, where its ability to manoeuvre enabled it to evade Sidewinder missiles. Because of its small size Pakistani pilots found it difficult to detect and follow in air action.

Indian pilots fared well, and where there was a matching chance in air combat they were not found wanting. They were however let down, firstly by the higher direction of the air war. IAF seemed to be fighting its own independent war. Its activities contributed only marginally to the course of the 1965 conflict. Secondly, committing obsolescent aircraft like the Toofani and Mystere in battle against superior performance aircraft like the American Sabre and Starfighter did not give the Indians an equal chance in air combat. The attrition rate was naturally high, and perforce the Air Force had to be liberal in dishing out awards to keep pilots in the air. Worst of all, the higher command failed to anticipate the requirements of a short war and evolve new concepts to suit Indian needs. For this Arjan Singh must squarely take blame as he was at the helm of affairs for almost six years before the conflict.

Although no official evaluation of IAF’s performance was made at the end of the conflict, its lessons were well imbibed by Lal. Well known for his managerial expertize, he set out with rare zeal to redress the shortfalls in basic concepts, infrastructure and organisational spheres. He changed the concept of the basic role of the service. Visualizing the need for optimum use of combat resources in arriving at decisions, he gave priority to the direct support of ground battle and insisted that re-equipping,, training and operational employment should be oriented towards this goal.He found that Air Headquarters itself as well as its command setup was organized on the Second World War pattern. Besides being top-heavy, the force functioned in watertight compartments and showed little concern for cost effectiveness. Lal proposed a complete overhaul of the organisation, and with his personality and sound arguments got the Government to accept his proposals. Broadly, the reorganisation reflected an emphasis on policy planning, while systems analysis introduced a progressive long-term outlook to keep the force in comparative combat trim. The days of hand-to-mouth existence were over.

Also read: Parameters for Indian Army 2020

In the field of logistics Ial reorganized the supplies and repair and maintenance organisation on a weapon-system basis so that the pipeline was not clogged by the intermeshing of conflicting requirements. In the operational field he insisted on speedier development of detection and communication systems so as to quicken the response to hostile action. An infrastructure of new airfields closer to the border and attendant servicing facilities were painstakingly created as a planned growth.

In training, the procedures and techniques for demanding air support for army formations and directing modern jet aircraft to targets was revised to cut down response time, and periodical exercises were undertaken in conjunction with the Army to perfect them further. Above all, Lal insisted on the immediate replacement of the obsolete inventory of Vampires, Toofanis and Mysteres and brought in more sophisticated aircraft. Although he was not able to achieve his planned goal, at the start of the Indo-Pak conflict in 1971, IAF had a definite superiority over PAF.

In 1971, India had 45 squadrons in all of combat and transport aircraft against Pakistan’s 13, compared with 34 and 12 respectively in 1965. The Vampire, Toofani and Mystere had been replaced by the Russian-built SU-7 to a large extent, and the 11 squadrons equipped with these aircraft had been reduced to only two. MIG-21 squadrons had simultaneously gone up from one to eight. PAF had acquired 90 Chinese MIG-19s, but their performance. was far inferior to the MIG-21, by then part manufactured in India. The MIG-21 could hold its own against Pakistan’s Starfighter, but it was no match for the recently acquired Mirage, of which Pakistan had about 24 by then.2

Notes:

- Asian Recorder, Vol I, p. 501.

- Asian Recorder, Vol XVIII, No 1, “Strength of Pakistani Air Force,” p. 10537.

The Mirage was superior in all respects including speed, sophisticated weapons system and manoeuvrability. Both sides were weak in deep-penetration bombing capability, but were near parity in bomber strength. India’s radar detection system, earlier interrupted by the US withdrawal of aid as a result of the 1965 conflict, was expanded with equipment acquired from other sources, and had considerably improved its effectiveness in the western sector by 1971 although some gaps existed in mountainous areas. The voids in low-looking fields were made up by raising an observer corps whose members, deployed close to the border, immediately reported whenever they saw or heard a plane passing overhead. Communications for speedy passage of this information were based on VHF wireless sets and by patching existing telegraph circuits.

Click to buy: India’s wars since independence

Pakistan had a good detection system in 1965, and India strove to improve its own through skilful employment of a combination of radar and observers. This detection system was completed just before the start of hostilities. It was an improvisation, but nonetheless an effective substitute for the more sophisticated electronic system under procurement according to a longterm plan. Air bases had been created in Kutch and Rajasthan so as to provide overlapping coverage of the entire western front to a great extent. Well camouflaged concrete pens had been provided for dispersing aircraft at forward airfields as a protection against a pre-emptive strike.

There was however a wide gap in the eastern theatre, where there was only one air base at Kumbhigram in the area east of East Pakistan. Fighters operating from this airfield could not adequately cover the Chittagong sea coast in the south. There was a civil airfield at Agartala which could be activated for military use if required, but because of its proximity to the East Pakistan border it was under machine gun and artillery fire and was therefore unusable till some territory in depth could be secured to eliminate this threat. An effort was made to construct another airfield on the Karimganj-Agartala road about 20 miles inside Indian territory in Tripura, but the project was conceived much too late to fructify in time. Responsibility for the uncovered southeastern coastline was accordingly taken over by the air arm of the Indian Navy.The division of air operational responsibility was rationalized. Western Air Command, with headquarters at Palam, was to be responsible for air defence and tactical air support for the entire western theatre, Eastern Air Command, with headquarters at Shillong, for the eastern theatre, and Central Air Command, with headquarters at Allahabad, for deep strategic bombing in its entirety and maritime reconnaissance. For close liaison and joint planning with the Army, Advance Air Command Headquarters were established with the Army’s Western and Eastern Commands at Simla and Calcutta respectively. Each corps and independent division headquarters was provided with a Tactical Air Centre Organisation so that close air support could be integrated in planning and day-to-day conduct of ground operations.Replacement and re-equipment would perhaps have proceeded in a leisurely fashion but for the start of US aid to Pakistan the same year.

A combined team of the Air Force and Army officers was positioned with formations down to brigades for control of and guidance to aircraft on targets. Signal communications were established for speedy and exclusive transmission of air support demands from the unit in contact with the Air Force wings allotted in support of land battles. Procedures for demand, screening and execution of a mission were streamlined and rehearsed during training so that when war came they were in a state of near perfection.

Lal fully appreciated the basic characteristic of flexibility in the air arm and felt that this could be fully exploited by switching aircraft at will from one task to another, and similarly from a dormant sector to more threatened areas, with ease. This necessitated interceptors, ground support, fighter and fighter-bomber aircraft functioning as composite teams, helping each other to achieve the ultimate aim in combat. It was common to see a mixture of Gnat, Hunter, MIG-21, SU-7 and Marut aircraft at forward bases. Aircraft like the Mystere, of comparatively poor performance value, were relegated to areas where the air situation was more favourable.

This aircraft mix created complex problems of maintenance and other service backing in the way of armament and so on, but these were solved under Lal’s able guidance. As a result, any combination of aircraft could be switched from one theatre to another, and within a theatre from one sector to another, and could function from any air base without upsetting the infrastructure or the pipeline. This endowed IAF with tremendous capability, which was exploited to the full.

Also read: IAF: The strategic force of choice

In addition, being a super-manager himself, Lal strove to make the optimum use of the available aircraft by harnessing any machine on the Air Force inventory which was airworthy. All training establishments were closed and trainer aircraft, along with instructors, functioned as combat units. In the event even Harvards, Vampires, Toofanis and Hunter trainers did their bit in war. There was some initial resistance to the use of mixes from ground engineers and operational men, but this was overcome by the persuasive Air Chief with patience and tact. He inspected each Air Force base personally to find an answer to the problems encountered with practical suggestions. To his credit, by the time war came every pilot and airman had developed full confidence in the concept.

On the eve of the Chinese invasion in 1962 IAF constituted the largest and most effective air power in the region.

The Chinese invasion in 1962 resulted in rethinking on air defence, both tactical and strategic. It was accordingly decided to divide the responsibility for air defence by ground weaponry against attacks at high and low levels. The responsibility for defence below 5,000 feet remained with the Army, while the Air Force took over the responsibility for dealing with aircraft and missiles flying above that level.