Perception is all too often reality. Add to the Afghan debacle syndrome that 31 out of 50 U.S. states are seen as insolvent. Some local governments are readying bankruptcy proceedings. State governments can only default; California is on the verge of taking up the option. State and local governments have unfunded retirement obligations of at least $2 trillion. But the United States still spends more on defence (Iraq and Afghanistan included) than the rest of the world put together. Paul Krugman, a Nobel Prize winner in economics, writes, “We are now, I fear, in the early stages of a third depression. It will probably look more like the Long Depression than the much more severe Great Depression. But the cost – to the world economy and, above all, to the millions of lives blighted by the absence of jobs – will nonetheless be immense.”1

In Afghanistan, the U.S. has violated the first principle of war, “Selection and maintenance of aim,” thereby axing any possibility of bringing the Afghan War to a successful conclusion.

Policies concerning Afghanistan cannot be viewed in a geostrategic vacuum but must be analysed within the framework of the prevailing global geopolitical mosaic, wherein the interactive ripple effect of actions and reactions induced by distinct policy decisions have direct bearing on the outcome of other unrelated geopolitical issues. More so in the case of the United States, whose interactions in the global sphere are much greater than other states. International and domestic policies are intricately meshed.

“Scarcely a day goes by without a major story about Afghanistan in mainstream newspapers and TV channels in Britain and America. The tone of these reports is increasingly sombre. More and more journalists and politicians are now convinced that the quicker western forces pull out, the better.”2

The writing on the wall is clear. Washington’s Afghanistan strategy is in a nearly irretrievable mess while there are many ongoing global and domestic policies that are in delicate circumstances and have a bearing on whatever decision President Obama may take.

The Afghanistan Development

To start with, it is pertinent to note that in the 8 years and 10 months that the American coalition forces have been fighting the so-called war against terrorism in Afghanistan, the chief executive in Washington, be it George W. Bush (Republican) or Barrack Obama (Democrat), has failed to enunciate a precise political or military objective,3 resulting in the launch of massive military forces into a political and strategic void. The result is best epitomised by an Indian phrase hawa maen lath marna. Military commanders with massive air and ground forces are waging a directionless war with no specific mission to achieve—consequently depleting human, material and monetary resources meaninglessly and weakening perceptions of American infallibility in the eyes of the world. In Afghanistan, the U.S. has violated the first principle of war, “Selection and maintenance of aim,” thereby axing any possibility of bringing the Afghan War to a successful conclusion.

“¦the occupation of Afghanistan and Iraq was the first step required to propel this larger strategic template.

This flaw was further compounded in March 2009, when President Obama attempted to spell out the objective for the ongoing war in Afghanistan through a white paper, “Affirming that the core goal of the US must be to disrupt, dismantle, and defeat al-Qaeda and its safe havens in Pakistan, and to prevent their return to Pakistan or Afghanistan.”4 Of note is the shift of the focus away from Afghanistan, further south, to Pakistan, thus introducing new, and hitherto unplanned for, mission objectives in the prevailing military operations.

The cause of this debilitating situation is the inability of the U.S. administration, which has many axes to grind, to fit the Afghanistan policy homogeneously into the larger national strategic matrix,5 which included occupying Iraq for access to its oil resources6 and military-basing facilities to stabilise the Middle East,7 creating a launch pad to restrain perceived Iranian aspirations to develop a nuclear weapons capability, gaining unfettered access to central Asian oil and gas resources8 by exercising influence/control over the central Asian states, extending the centre of gravity of the U.S. security matrix into Asia by subverting the southern states of the Russian federation by extending the NATO footprint eastward9, containing the extension of Chinese influence westward10, and so on. Actually, the occupation of Afghanistan and Iraq was the first step required to propel this larger strategic template. However, the belief, amongst the Bush administration in general, and the Rumsfeld-led Pentagon in particular, of the absoluteness of the American military power led to discordant initiatives that ate into the resources required to coherently apply all political, military and economic might into completing the very first phase of its strategic programme, i.e. total subjugation of Afghanistan.

In its tenth year, the American war against terrorism in Afghanistan is a grievously threatened operation, with dwindling military resources, domestic political pressures demanding termination and troop withdrawal, and increasing human and fiscal costs of supporting logistics to sustain the military operation bordering on the unaffordable.

| Editor’s Pick |

The recent collapse of the Dutch government was brought about by a dispute over demands to withdraw the country’s troops in Afghanistan11. Consequently the 2,000 Dutch soldiers fighting in the southern Afghan province of Uruzgan look certain to be pulled out this year after the prime minister, Jan Peter Balkenende, a Christian Democrat, failed to persuade his coalition partners in the Labour Party to extend the mission beyond August, when it is due to end. This has reinforced fears that NATO’s front is crumbling and that other Western nations may bow to mounting domestic public pressure to withdraw their forces. Current indicators are that Canada intends to commence withdrawing its forces with effect from 1 July 2011,12 and Germany is to begin its pullout from Afghanistan in 2011, gradually, which is expected to last through 2013.13 Even the British prime minister indicates that he wants all British soldiers to return home before the next general election, in 2015.14 The rats appear to be leaving the sinking ship. A simple addition shows that this will result in the larger portion of NATO troops being withdrawn, leaving the United States holding the baby it had conceived.

“¦reinforced fears that NATOs front is crumbling and that other Western nations may bow to mounting domestic public pressure to withdraw their forces.

Added to this, domestic resistance to Washington’s war is also mounting to the point that it is no longer a tenable policy. According to an Agence France-Presse report, a group of U.S. lawmakers, led by representative John Conyers, allied with the White House, has joined the “Out of Afghanistan Caucus” opposing continued combat and called for an end to the Afghan War, labelling it an unwinnable drain on U.S. “blood and treasure” and comparing it to Vietnam.15

“On 01 December 2009, President Obama laid out his Afghanistan war strategy in an address at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. The President, while giving out his policy for a surge in US troops also gave out a time line of 18 months for withdrawal of US forces. A few days later, in their testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Hillary Clinton, Admiral Mullen and Robert Gates stated that they would execute this transition responsibly, taking into account conditions on the ground and that a review of the Afghanistan strategy would be carried out at the end of 2010. When contacted to resolve this apparent contradiction, the White House spokesperson reiterated that the US would withdraw in 18 months. The contradiction remains, for while the intent to withdraw is clear, it may perhaps be contingent on the situation existing at that time.”16

The writing on the wall is clear. Washingtons Afghanistan strategy is in a nearly irretrievable mess while there are many ongoing global and domestic policies that are in delicate circumstances and have a bearing on whatever decision President Obama may take.

So, the situation as it is on the ground in July 2010 is as follows:

The U.S. is:

In the unenviable position of trying to extricate its military from Iraq, which in time would erode its strategy to establish its foothold in the Middle East

- Under pressure to open a front against Iran in response to its non-proliferation strategy and the need to demonstrate its will to support its closest ally, Israel, thereby having to contain Iran by deploying military forces in Azerbaijan, the Persian Gulf and Afghanistan

- Struggling to maintain a meaningful military and political presence in the Caucasus and the Black Sea and on the threshold of being deserted by its NATO allies in Afghanistan and shouldering the military, economic and political costs of sustaining its war to occupy Afghanistan

- Taking incremental military and economic initiatives to suppress Pakistani-based militancy and stifling any possibility of that country’s nuclear capabilities falling into the hands of terrorist organisations

- Coping with piracy in the Arabian Sea off the Coast of Somalia

- In the process of establishing a military footprint in Africa with the recently created United States African Command (USAFRICOM)

- Struggling with the political dynamics of military basing in Japan to secure its East Asian assets and add to the credibility to guarantee a nuclear umbrella

- Trying to contain growing Chinese maritime potential, which threatens to neutralise America’s hitherto unchallenged capabilities to go to the defence of its allies in the Asia Pacific region.

There are numerous debilitating domestic economic, political and security issues that further erode the existing comprehensive power potential of the United States that are not being enumerated here. Suffice it to say that these issues are exacerbated by the economic17 and political strains of executing the military posture enunciated above and play a major role in Washington’s decision-making process vis-à-vis the future of its involvement in the war in Afghanistan, i.e. the fifth Afghan war after the British and Soviet misadventures.

“The war, as every Afghan watcher knows, is going badly for the US and North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) forces. June was the worst month for foreign troops in that country with 102 combat deaths, which is the highest level of monthly casualties since the beginning of the war”¦”

In view of the above, it is safe to assume that President Obama will be taking some major decisions about the U.S. war in Afghanistan before the year is out that would have serious implications for the south, west and central Asian countries as also the foreign policies of the major powers. The process will entail clearly enunciating American objectives and prioritising the missions that need to be accomplished.

The possible options are to hunker down and continue the war till the U.S. suppresses the adversarial forces into submission, which may take 10 to 15 years, provided the U.S. has the economic, political and military staying power.18 In the prevailing situation, one can safely rule out this option.

The alternate is to cut losses and withdraw from Afghanistan, leaving the region to its devices. “The war, as every Afghan watcher knows, is going badly for the US and North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) forces. June was the worst month for foreign troops in that country with 102 combat deaths, which is the highest level of monthly casualties since the beginning of the war. Also, the Afghan war by end June had officially become America’s longest war in history, longer than even Vietnam”.19

But stepping away from the imbroglio the United States has produced in Afghanistan is easier said than done. If Washington were to abandon Kabul as it did Vietnam, without putting into place an Afghan entity, regional states will scramble to pick up the spoils. Washington’s credibility as a superpower will be irretrievably damaged, leaving it vulnerable to the vicissitudes of international community, sucking in other major powers to fill the vacuum so created. Therefore, Washington has to create a modicum of stability, thereby securing some, if not all, of United States’ interests in the region, enumerated earlier. Therefore, Washington needs to, before the end of the year, establish appropriate political and military structures and systems whereby its interests can best be salvaged through complete or partial withdrawal of its presence in Afghanistan.

Washington needs to, before the end of the year, establish appropriate political and military structures and systems whereby its interests can best be salvaged through complete or partial withdrawal of its presence in Afghanistan.

As the U.S.–NATO-led war in Afghanistan to cleanse that country of anti-West Islamic forces has come to a standstill, it is evident that those apparent objectives earlier stated by Washington, London and Brussels will not be met. The war in Afghanistan may end next year, or 10 years later, but the fact remains that the U.S.–NATO troops have no other option but to bring about an end to this war by putting in the seat of power Afghans who may or may not be hard core Taliban. But the process will be a complicated one, with various geopolitical, and regional, forces making their input.

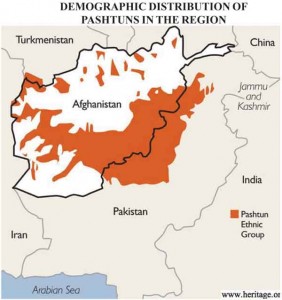

One such geopolitical option is to set in motion a process that will lead to the combining of the Pashtuns of the region and the formation of a Pashtunistan.20 “De facto partition is clearly not the best outcome one can imagine for the United States in Afghanistan. But it is now the best outcome that Washington can achieve consistent with vital national interests and U.S. domestic politics.”21

Greater Pashtunistan: To Who’s Benfit?

As it is, Afghanistan has never accepted the Durand Line23 as its international boundary with Pakistan.

Some “observers have contemplated, if the AfPak policy ends in failure, instead establishing a de facto, if not de jure, independent ‘Pashtunistan’, or Pakhtunkhwa as it is known in Pashto? This is a concept with a long history.

There are claims that nationalist sentiment is still bubbling just beneath the surface in the Pashtun areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan, and that whatever popular support there is for the Afghan and Pakistan Taliban among Pashtuns is based more on this sentiment than on a deep and abiding attraction to jihadi militancy.”24

Such a nation will not be born through negotiations across the table but would require a long-drawn-out uprising and bloodletting, which the Pakistani army, more than the Afghan National Army (ANA), will militarily oppose vigorously.

Such a nation will not be born through negotiations across the table but would require a long-drawn-out uprising and bloodletting, which the Pakistani army, more than the Afghan National Army (ANA), will militarily oppose vigorously.

That would then pitch the Islamic moderate-dominated powerful Punjabi faction of the Pakistani army against the less moderate and more fundamentalist Pashtuns living in Pakistan’s tribal areas and North West Frontier Province (NWFP).

Continued…: Salvaging Americans Botched Strategic Foray into Asia – II