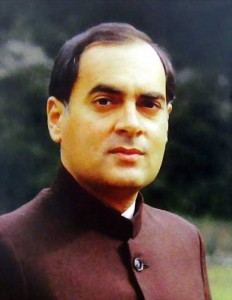

During the little over five years he was the Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi had three chiefs of the R&AW. G.C.Saxena, an IPS officer of the UP cadre,who had taken over as the chief in April, 1983 when Indira Gandhi was the Prime Minister, continued till his superannuation in March 1986. S.E.Joshi, an IPS officer of the Maharashtra cadre, who succeeded him, retired in June 1987, after having served as the chief for 15 months. Rajiv Gandhi was keen that he should continue so that he had a tenure of three years like his predecessor, but Joshi felt it would be unfair to his successor.

During the little over five years he was the Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi had three chiefs of the R&AW. G.C.Saxena, an IPS officer of the UP cadre,who had taken over as the chief in April, 1983 when Indira Gandhi was the Prime Minister, continued till his superannuation in March 1986. S.E.Joshi, an IPS officer of the Maharashtra cadre, who succeeded him, retired in June 1987, after having served as the chief for 15 months. Rajiv Gandhi was keen that he should continue so that he had a tenure of three years like his predecessor, but Joshi felt it would be unfair to his successor.

An officer of the Tamil Nadu cadre was to succeed him, but Rajiv Gandhi reportedly got annoyed with him because he was unaware of the Bofors scandal when it broke out in the Swedish electronic media. He had him shifted as the Chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee and designated A.K.Verma, an IPS officer of the Madhya Pradesh cadre, as the chief. He had a full tenure of three years—-partly under Rajiv Gandhi and partly under V.P.Singh.Saxena, like Kao and Suntook, was suave in his behaviour and gentle in his words, but hard-hitting in action. Joshi and Verma were more like Sankaran Nair—anything but suave, blunt in words and hard-hitting in action. Like Sankaran Nair, Saxena, Joshi and Verma were experts on Pakistan and political and militant Islam. Saxena, Joshi and Verma knew more about Pakistan than any other expert in India or abroad. Saxena had never served in the Islamic world, but he had been dealing with Pakistan right from the day he joined the R&AW shortly after its formation. He did not have much to do with Pakistan only during his posting in Rangoon in the 1970s. Joshi was the only chief of the R&AW to have served in Pakistan. Verma had served in Kabul and Ankara and had been dealing with Pakistan and the Islamic world during most of his postings in the headquarters.Sankaran Nair and Verma were held in awe and respect in Pakistan’s intelligence and policy-making communities.They knew of the active role played by Nair under Kao in the liberation of Bangladesh and of Verma’s reputation as a mirror image of Nair—-as an officer who would like nothing better than to break Pakistan again if he was given the go-ahead by India’s political leadership. During my posting in Geneva and subsequently in headquarters, I had much to do with Pakistan and with various sections of the Pakistani civil society and Government.

An officer of the Tamil Nadu cadre was to succeed him, but Rajiv Gandhi reportedly got annoyed with him because he was unaware of the Bofors scandal when it broke out in the Swedish electronic media.

I could see for myself that those, who had an opportunity of interacting with Verma, looked upon him as one of the very few Indians who had a really good understanding of the Pakistani psyche and of the Pakistani military mind-set. I have no doubt in my mind that if Rajiv Gandhi had not lost the elections in 1989 and if Verma had continued as the chief of the R&AW under Rajiv Gandhi for two or three years more, Pakistan would not be existing in its present form today and innocent civilians in our country would not be dying like rats at the hands of jihadi terrorists.

There was a strong convergence of views between Rajiv Gandhi and Verma that unless Pakistan was made to pay a heavy price for its use of terrorism against India, India would never be free of this problem. The process of re-activating the R&AW’s covert action capability, which had remained in a state of neglect under Morarji Desai, started after Indira Gandhi returned to power in 1980. Suntook, Saxena and Joshi played an active role in carrying forward this process, but it was Verma, who gave the R&AW once again the strong teeth, which it was missing since 1977, and made it bite again.

Well-deserved tributes have been paid to the Punjab Police under K.P.S.Gill, the IB under M.K.Narayanan, the National Security Guards under Ved Marwah, the other central para-military forces and the Army for their role in restoring normalcy in Punjab. But, the Indian public and the political leadership as a whole barring the Prime Minister of the day hardly knew of the stealth role played by Saxena, Joshi and Verma in making our counter-terrorism success in Punjab possible. While Saxena and Joshi laid the foundation for an active and strong liaison network and for improving the R&AW’s capability for the collection of terrorism-related HUMINT, Verma gave the R&AW the teeth which made Pakistan realize that its sponsorship of terrorism would not be cost-free.

All the three of them were fortunate in having Rajiv Gandhi as their Prime Minister. Rajiv Gandhi came to office as the Prime Minister with very little knowledge of the intelligence profession and of the Indian intelligence community. When Indira Gandhi was the Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi used to take an active interest in the physical security arrangements for her after Operation Blue Star. She used him often in her attempts to find a political solution to the problem in Punjab. Many of his clandestine meetings in this connection were organized by the R&AW when Saxena was the chief. Beyond that, he had very little interaction with the R&AW and very little knowledge of it before he became the Prime Minster.

Rajiv Gandhi came to office as the Prime Minister with very little knowledge of the intelligence profession and of the Indian intelligence community.

It used to be said that after he took over as the Prime Minister, he was amazed—–even somewhat disturbed—– when Saxena briefed him at a one-to-one meeting on the sensitive on-going operations and covert actions of the R&AW. It was also said that while he did not have the least hesitation in approving the continuance of all the R&AW operations relating to Pakistan, China and Bangladesh, he was somewhat confused in his mind regarding the wisdom of the operational policies followed under his mother in relation to Sri Lanka . He took some time to make up his mind on Sri Lanka. Ultimately, he decided to continue on the lines laid down by his mother in relation to Sri Lanka too.

It would be incorrect to characterize his operational policy towards Pakistan as a carbon copy of the policy followed by Indira Gandhi. There were nuances, which differed from those of his mother. Indira Gandhi came to office with a strong dislike and distrust of Gen.Zia-ul-Haq, which continued till her death. She was convinced in her mind that Zia was not a genuine person and that his expression of warmth and bonhomie towards Indians was contrived. And the fact that Zia and Morarji Desai got along comfortably with each other prejudiced her mind against him.

Rajiv Gandhi did not inherit his mother’s anti-Zia prejudices. He was fully aware of the role played by the ISI in supporting terrorism in Punjab. The suspicion that the ISI under Zia might have been behind the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her security guards was never proved, but it kept haunting the minds of some persons (including me) during the 1980s. Despite this, Rajiv was prepared to consider meaningful ideas for a co-operative relationship with Pakistan. His ready acceptance of the offer of the then Crown Prince Hassan of Jordan to arrange a dialogue between the chiefs of the ISI and the R&AW to which a reference had been made in an earlier chapter was a typical example of his open mind to such initiatives.

At the same time, Rajiv Gandhi was convinced—as strongly as his mother was—- that India’s preoccupation had to be not with individual Pakistani leaders, who are a passing phenomena, but with the Pakistani mindset, which was an enduring phenomenon right rom the day Pakistan was born in 1947. In India, there is no such thing as an enduring Indian mindset towards Pakistan. The mindsets keep changing with leaders and circumstances. It is not so in Pakistan.

The compulsive urge to keep India weak, bleeding and destabilized influences policy-making in Pakistan— whoever be the leader, civilian or military. It has nothing to do with its humiliation in Bangladesh in 1971. It was there before 1971 and it has been there since 1971. Some leaders such as those of the fundamentalist parties openly exhibit it, but others manage to conceal it behind seeming warmth in their behaviour. Till that mindset changes, India has to adopt a mix of incentives and disincentives in its operational policies towards Pakistan—incentives towards a co-operative relationship and disincentives to discourage hostile actions.On the need for a mix of incentives and disincentives, Rajiv Gandhi, Saxena, Joshi and Verma were on the same wavelength. Rajiv Gandhi’s ready acceptance of Crown Prince Hassan’s offer was an example of such an incentive. It was fully backed by the R&AW without any mental reservations, though it did not ultimately produce the desired results. As examples of disincentives, one could mention the timely and effective pre-emption of Pakistani designs to use the Siachen glacier to weaken the Indian position in the Kargil and Ladakh areas and the use of the R&AW’s covert action capability to make Pakistan realize that it would have to pay a heavy price for its use of terrorism against India in Punjab.Another component of the operational policy followed under Rajiv Gandhi was to frustrate Pakistan’s goal of a strategic depth in Afghanistan.

The policy of frustrating Pakistan’s goal in Afghanistan was actually initiated under Indira Gandhi by Kao immediately after the formation of the R&AW in 1968. Strong relationships at various levels—-open as well as clandestine— were established not only with the people and the rulers of Afghanistan, but also with the Pashtuns of Pakistan. India’s desire for close relations were readily reciprocated by the Afghan people and rulers and by large sections of the Pashtun leadership. The networks established in the 1970s continued to function even after the occupation of Afghanistan by the Soviet troops and the installation in power of a succession of pro-Soviet regimes in Kabul.

When Indira Gandhi was the Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi used to take an active interest in the physical security arrangements for her after Operation Blue Star. She used him often in her attempts to find a political solution to the problem in Punjab.

The Soviet Union blessed and welcomed this networking and helped it grow in strength in whatever way it could. This networking created misunderstanding in India’s relations with the Afghan Mujahideen leaders. They were hurt and disappointed by India’s reluctance to support their struggle against the Soviet occupation, but these feelings of hurt and disappointment did not turn them hostile to India. Many Afghan Mujahideen leaders—Pashtun as well as Tajik— maintained secret contacts with the R&AW even while co-operating with the ISI and the CIA against the Soviet troops in Afghanistan. Rajiv Gandhi fully supported this policy.

Thus, Saxena, Joshi and Verma under Rajiv Gandhi’s leadership followed a triangular strategy towards Pakistan—-co-operative relations where possible, hard-hitting covert actions where necessary and close networking with Afghanistan.

This policy started paying dividens in Punjab even when Rajiv Gandhi was the Prime Minister in the form of reduced ISI support for the Khalistanis, but this did not prevent the ISI from interfering in a big way in J&K from 1989. The successors of Rajiv Gandhi as the Prime Minister had the good sense to realize that this was an argument not for discontinuing Rajiv Gandhi’s policy, but for further strengthening it. This triangular strategy was continued with varying intensity under the successors to Rajiv Gandhi, but, unfortunately, Inder Gujral, who was the Prime Minister in 1997, discontinued it under his Gujral Doctrine. He ordered the R&AW to wind up its covert action division as an act of unilateral gesture towards Pakistan. His hopes that this gesture would be reciprocated by Pakistan were belied. His policy towards Pakistan became one of unilateral incentives with no disincentives.

However, he had the good sense not to change the operational policy in respect of Afghanistan as laid down by Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi. It continued to pay dividends. So far as dealing with Pakistan is concerned, we have had no coherent strategy since 1997. The innocent civilians of India are paying a heavy price for this at the hands of the jihadi terrorists trained, armed and used by the ISI to keep India bleeding.

He (Rajiv Gandhi) was fully aware of the role played by the ISI in supporting terrorism in Punjab.

The PSYWAR division of the R&AW, which had been wound up under the budgetary cut imposed by Morarji Desai, was revived after the return of Indira Gandhi to power and further strengthened under Rajiv Gandhi. An officer of the Indian Information Service, who had worked in the R&AW before 1977, was re-inducted to revive the PSYWAR Division. The work of this Division was largely focused on countering the ISI’s disinformation campaign against India and providing the dissident elements in Pakistan with the means of having their views disseminated inside and outside Pakistan. This revived PSYWAR Division was to do very good work when jihadi terrorism broke out in a big way in J&K in 1989, when V.P.Singh was the Prime Minister. This would be discussed later.

Rajiv Gandhi took great interest in the modernization and computerization of the R&AW. Under the modernization programme, its TECHINT capability was considerably increased. This was made possible through adequate investments for strengthening its capability for satellite communications monitoring, for aerial surveillance through the ARC and for the use of technical means in the collection of HUMINT. Prior to 1980, the R&AW’s capability for the collection of communications intelligence (COMINT) was largely confined to tapping landline telephones, which needed a human intervention to get access to the line. Before and during the 1971 war, its Monitoring Division was also able to intercept telephone conversations between the two wings of Pakistan. However, its capability for the interception of Pakistan’s overseas telephone communications was limited. The investments in satellite monitoring in the 1980s overcame these limitations to a considerable extent.

While the investments in the ARC improved the R&AW’s capability for the collection of electronic intelligence (ELINT), those in its technical laboratories added to its capability for the collection and dissemination of HUMINT. These investments were in fields such as secret writing, clandestine photography, wireless communications under hostile conditions, clandestine recording of communications and scrambling of telephone communications. Its Science and Technology Division continued to do good work in the collection of intelligence regarding Pakistan’s nuclear and missile programmes.

When Indira Gandhi was the Prime Minister, Kao was able to see that any differences between the R&AW and the Armed Forces regarding their respective roles in the collection of military intelligence were always sorted out in favour of the R&AW.

The R&AW’s Pakistan Division was the main beneficiary of the improvements brought about by the fresh investments under Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi. Morarji Desai’s budget freeze had resulted in a stagnation of the organization’s TECHINT capability. This process was reversed and then the capabilities further improved. However, the Armed Forces continued to voice dissatisfaction over the gaps in the collection of military intelligence relating to Pakistan. Their constant complaint was that while the R&AW was able to collect Pakistani military intelligence relating to overseas procurement, new raisings, deployments etc, its ability to collect intelligence regarding the future plans of the Pakistani Armed Forces, their military exercises, the deficiencies noticed during those exercises, their war games, their future intentions etc remained inadequate.

Our Armed Forces—particularly the Army—therefore started demanding that they should also be permitted to collect external intelligence outside the Indian territory through human sources and to make similar investments for strengthening their TECHINT capability.

When Indira Gandhi set up the R&AW in 1968, she had laid down that it would be exclusively responsible for the collection of external intelligence. Kao and those, who followed him as the chief, interpreted this to mean HUMINT as well as TECHINT. In respect of HUMINT, they took up the stand that while the Army could collect tactical military intelligence upto a limited depth across India’s international borders through intelligence collection posts set up along the borders, it could not run clandestine source operations outside Indian territory through military officers posted under cover outside the country. They insisted that any military officer posted outside the country for clandestine intelligence collection had to be from the R&AW.

A practice also grew up under which all proposals from the Armed Forces for substantial investments for improving their TECHINT capability were referred to the head of the R&AW for his concurrence. The R&AW particularly was adamant in its refusal to let the Army develop its own capability for satellite monitoring to supplement that of the R&AW. These issues, which were a source of dissatisfaction to the Armed Forces, were agitated upon by them much more vigorously under Rajiv Gandhi than they were able to do under his mother. When Indira Gandhi was the Prime Minister, Kao was able to see that any differences between the R&AW and the Armed Forces regarding their respective roles in the collection of military intelligence were always sorted out in favour of the R&AW.

While the R&AW continued to maintain its monopoly approved by Indira Gandhi in respect of HUMINT, the process of weakening its monopoly in respect of TECHINT started under Rajiv Gandhi.

After her assassination and the final exit of Kao from the intelligence community, the R&AW did not have the same kind of clout with Rajiv Gandhi as it had with Indira Gandhi. As a result, while Rajiv Gandhi ruled in favour of the R&AW in respect of HUMINT, he was more open to the arguments of the Armed Forces in respect of TECHINT. Proposals from the Armed Forces for substantial investments for improving their TECHINT capability—particularly in the field of satellite monitoring— received a sympathetic consideration from Rajiv Gandhi.

While the R&AW continued to maintain its monopoly —approved by Indira Gandhi— in respect of HUMINT, the process of weakening its monopoly in respect of TECHINT started under Rajiv Gandhi. But its progress was slow and reached its culmination only after the Kargil conflict of 1999 when a decision was taken to set up a separate agency for future investments in TECHINT and to allow not only the Armed Forces, but also the IB to improve their TECHINT capabilities without making their proposals subject to a veto by the R&AW.

After the exit of Kao, not only the Army, but also the IB started questioning the exclusive authority for the collection of external intelligence—HUMINT as well as TECHINT— entrusted by Indira Gandhi to the R&AW in 1968. The IB expressed dissatisfaction over the R&AW’s coverage of external intelligence having a bearing on India’s internal security. It was particularly critical of what it projected as the inadequate intelligence flow from the R&AW on the activities and plans of the Khalistani terrorists. Some officers of the IB, who were unhappy over the bifurcation of the IB by Indira Gandhi in 1968, now started insisting that the Government should have a second look at the orders passed by her in 1968. They even questioned the wisdom of her orders that the R&AW would be responsible for liaison with foreign intelligence agencies and that all contacts of other agencies such as the IB with foreign intelligence agencies would be only through the R&AW. Their argument was that since many of India’s internal security problems had external linkages, the IB, which was responsible for internal intelligence, should also be in a position to collect independently intelligence about the external linkages—-either through its own source operations or through liaison with foreign security agencies. They felt that the IB should not be solely dependent on the R&AW for this purpose.

To start with, the IB was keen to have its own officers posted in the Indian High Commission in London and in the Indian Embassy in Washington DC to monitor the activities of the Khalistani elements in the UK and the US and to liaise with the local security agencies on this subject. The R&AW agreed to this when Saxena was the chief. Since then, the IB has been raising from time to time the question of their having their own officers in all our neighbouring countries to collect intelligence having a bearing on our internal security.

This is in addition to the posts in our important diplomatic missions abroad, which have been created for looking after the physical security of the missions and which have been filled up either by IPS officers from the IB or by IPS officers taken directly from the States. Thus, two parallel set-ups have come up abroad defeating the ideas and intentions of Indira Gandhi—–the R&AW set-up and the IB set-up. Can the Indian tax-payer afford this luxury? Has this resulted in an improvement in the intelligence flow? Has this reduced the threats to our internal security? These are questions, which need to be objectively considered.For the IB, which is responsible for counter-intelligence, the ISI and its officers posted under diplomatic cover in the Pakistani High Commission in New Delhi, are the most important targets. For the ISI, the R&AW and its officers posted in the Indian High Commission in Islamabad and before 1994 in the Indian Consulate-General in Karachi under diplomatic cover are the most important targets.

This was so even before 1968 when IB officers used to be posted in Karachi and Islamabad under diplomatic cover. The intelligence agencies of all countries post their officers under diplomatic cover in foreign countries to collect intelligence. There is nothing unusual about this.

On many occasions, the IB had caught intelligence agencies of the US and other Western countries trying to penetrate us through their officers in Delhi.

The counter-intelligence agencies keep a careful eye on them and if they find that they are trying to penetrate the host Government, its intelligence agencies and security forces, they catch them and quietly expel them without ill-treating them. A certain civility is observed even in counter-intelligence. The same is the case in India and Pakistan also in respect of all intelligence officers except those of each other. On many occasions, the IB had caught intelligence agencies of the US and other Western countries trying to penetrate us through their officers in Delhi. It asked the MEA to quietly expel them without sensationalizing their activities.

However, these ground rules do not apply to the intelligence officers of India and Pakistan. The ISI does not allow suspected Indian intelligence officers to function and lead a normal life. It keeps them under permanent surveillance and taps their telephones all the time. There is nothing secret about the surveillance. I used to call it bumper-to-bumper surveillance. If the ISI caught any R&AW officer under suspicious circumstances, it beat him up and even administered electric shocks to him before expelling him from Pakistan despite the fact that he enjoyed diplomatic immunity from arrest and ill-treatment. If criminals are subjected to third degree methods, they can at least approach a court or a human rights organization for justice. When intelligence officers are subjected to third degree methods, they have to grin and bear it.

The IB is not a saint. It does almost the same thing to suspected ISI officers posted in New Delhi. The only difference is that the IB does not administer electric shock. At least, it never used to when I was in service. Considering the brutal manner in which the IB and the ISI treat the suspected intelligence officers when caught, it is a wonder how R&AW officers volunteer for posting in Pakistan and those of the ISI volunteer for posting in India. It is equally a wonder how they manage to collect intelligence when posted to each other’s country.

…the ISI issued a secret circular to all public servants warning that the R&AW had started using attractive women for honey traps and asking them to report to it if any Indian woman approached them. It also said that about 50 attractive Indian women had been infiltrated by the R&AW into Punjab to organize honey traps.

When I joined the IB in 1967, a senior officer of the Ministry of Home affairs (MHA) narrated to me a funny incident (he swore it was true) which illustrated the way the IB and the ISI treated each other. The IB used to maintain a permanent bumper-to-bumper surveillance on a suspected ISI officer posted in the Pakistani High Commission in New Delhi. Once, in winter, there was a heavy fog reducing visibility. The suspected ISI officer was returning home after a dinner outside. The IB’s surveillance car followed him very closely. After he had driven for some time, the suspected ISI officer stopped his car. The IB’s car also stopped. The ISI officer got out, walked to the IB’s car and asked the head of the IB’s surveillance team: “Care to come in for tea?” Only then, the IB team realised that while following the ISI officer’s car bumper-to-bumper in poor visibility, they had entered his house without noticing it. The embarrassed IB team apologized, declined the invitation and drove back.

One can write a humorous book on the way IB/R&AW and ISI officers operate in each other’s country and try to discourage the local people from interacting with the intelligence officers of the adversary. Once (before 1968) the source of an IB officer in the Pakistan Army headquarters told him he had managed to get hold of a classified document of the Army, but said he would not be able to let him take it to the mission for photostating. He said he would have to return it to him on the spot after perusal. The officer fixed his meeting with the source in a public park. He took with him his Personal Assistant along with a portable type-writer. He took the document from his source and his PA started typing it. The ISI surveillance team caught the officer and his PA and expelled them. Shocking, but true.

When Narasimha Rao was the Prime Minister, there were rumours in Pakistan that Nawaz Sharif, the then Prime Minister, had developed a romantic relationship with the sister of a well-known Bollywood actor. Worried over this, the ISI issued a secret circular to all public servants warning that the R&AW had started using attractive women for honey traps and asking them to report to it if any Indian woman approached them. It also said that about 50 attractive Indian women had been infiltrated by the R&AW into Punjab to organize honey traps. The news of this circular leaked out.

The “Frontier Post” of Peshawar came out with a humorous editorial which made the following appeal to the R&AW: “ Why this partiality to the Punjabis? Why send your attractive women only to them? We Pashtuns also like attractive women. Send us at least 10. Many of us are dying to be honey-trapped by attractive Indian women.”

Sharad Pawar, who was then the Defence Minister, told a woman journalist working for a Delhi paper that the R&AW was tapping the telephone conversations of Nawaz Sharif with the sister of the actor and that it had secret recordings of Nawaz sharif singing love songs to her over telephone.

Sharad Pawar, who was then the Defence Minister, told a woman journalist working for a Delhi paper that the R&AW was tapping the telephone conversations of Nawaz Sharif with the sister of the actor and that it had secret recordings of Nawaz sharif singing love songs to her over telephone. Greatly excited that she got a scoop, she promptly carried it in her paper. A couple of days later, she got a defamation notice from the sister of the actor. She rushed to Sharad Pawar and sought his assistance for challenging the defamation notice. She wanted somebody in the Government of India to give her a letter that what she reported was correct. Sharad Pawar totally denied ever having told her anything about the relationship of this woman with Nawaz Sharif. “ I don’t even know who she is. Where is the question of my talking to you about her?”

In utter panic, she approached the late Amitabha Chakravarthi of the Indian Information Service, who was then on deputation to the R&AW, and sought our help to enable her to reply to the defamation notice. I asked Amitabha to tell her that the question did not arise since we were not aware of any relationship between the sister of the actor and Nawaz Sharif.

Such lighter moments were more an exception than the rule. Most of the time, the Indian and Pakistani agencies were brutal towards each other. Very often, it was the R&AW officers posted in Pakistan, who had to bear the brunt of the ISI’s brutality in retaliation for what they alleged was the IB’s brutality towards their diplomats in New Delhi. Such instances of mutual brutality increased under Zia-ul-Haq in Pakistan and Rajiv Gandhi in India.In 1988, the IB trapped Brig.Zaheer-ul-Islam Abbasi, a suspected ISI officer posted as Military Attache in the Pakistani High Commission in New Delhi, and had him thoroughly beaten up.

The ISI retaliated in their usual manner against an Indian diplomat in Islamabad whom they suspected to be from the R&AW. The R&AW strongly protested to the IB against such actions being taken in New Delhi without even alerting it beforehand. The IB rejected the protest. The practice of ill-treatment of suspected intelligence officers posted in the capital of each other has continued till today. This needs to be stopped since it serves no purpose. It only adds to the mutual bitterness.

The R&AW played an important role in the normalization of relations between India and China for which it received high praise from Rajiv Gandhi. Before the assassination of Indira Gandhi, the Yugoslav intelligence, with which the R&AW had an excellent liaison relationship, had organized an invitation for Kao from China’s external intelligence agency, known as the Ministry of State Security (MSS). Kao flew to Beijing via Tokyo. He was accompanied by G.S.Mishra, one of the R&AW’s leading experts on China who had served in Beijing for some years, Dr.S.K.Chaturvedi, who used to be the head of the Economic Intelligence Division of the R&AW, and B.K.Ratnakar Rao, an IPS officer from the Tamil Nadu cadre, who had served for many years as the Staff Officer of Kao.The visit had two objectives— to lay the foundation for a liaison relationship between the R&AW and the MSS and to test the waters in China for a possible visit by Indira Gandhi to mark the normalization of the relations between the two countries. Two days after their arrival, as his talks with the Chinese political leaders as an emissary of Indira Gandhi and with senior Chinese intelligence officials were proceeding smoothly, Indira Gandhi was assassinated. He had to cut short the visit and return to Delhi via Hong Kong.

After Rajiv Gandhi took over as the Prime Minister, the R&AW briefed him on the visit of Kao to Beijing and its purpose. He was appreciative of the initiative taken by Kao and the R&AW and wanted the R&AW to pursue its efforts to set up a liaison relationship with the MSS and to pave the way for a visit by him to Beijing. The R&AW succeeded in establishing a liaison relationship with its Chinese counterpart. Not only that. Even a hotline was established between the chiefs of the two services so that not only the two chiefs, but also the Prime Ministers of the two countries could use this for the exchange of sensitive communications for which they wanted to avoid using the normal diplomatic channel between the Foreign Offices of the two countries.

The R&AW played an important role in the normalization of relations between India and China for which it received high praise from Rajiv Gandhi.

Rajiv Gandhi accepted an invitation from the Chinese leadership to visit China in 1988. Much of the preparatory work for this visit, including the mutual consultations on the joint statement on the border dispute between the two countries to be issued at the end of the visit, was done through this hotline. Rajiv Gandhi also sent A.K.Verma on a top secret visit to China to ensure that his own visit and talks with the Chinese leaders would be successful. Rajiv Gandhi prepared himself thoroughly for the visit. He read diligently all the background notes on Sino-Indian relations prepared by the MEA and the R&AW. He also had discussions with some of the Indian experts on China. At his request, the R&AW arranged a secret visit to New Delhi by two China experts of the UK’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) to brief Rajiv Gandhi on the Chinese negotiating techniques and other matters of relevance.

The visit of Rajiv Gandhi to China in December,1988, was highly successful and marked the culmination of the process of normalization of the diplomatic relations between the two countries. The high point of his visit was his very warm meeting with Deng Xiao-ping, which sent a significant message across to the people of the two countries and to the international community regarding the determination of the two countries to strengthen their mutual friendship and co-operation. On his return to India, Rajiv Gandhi had nothing but the highest praise for the role of the R&AW and Verma in contributing to the success of his visit.

When Narasimha Rao visited China as the Prime Minister in September,1993, his programme as drawn up by the Chinese was almost a carbon copy of the programme for the visit of Rajiv Gandhi except for one difference. It did not provide for a meeting with Deng. Rao felt disappointed and was very keen to have a meeting, however brief, with Deng. The Chinese authorities expressed their inability to accommodate his request on the ground that Deng was not well. Rao, who was aware of the role of the R&AW in connection with the visit of Rajiv Gandhi to China, sought its help in arranging a courtesy call by him on Deng. The R&AW took up the matter with the MSS through the hotline. It replied that Deng had not received Russian President Boris Yeltsin due to indisposition and that if they made an exception in the case of Rao, their action could be misunderstood by Moscow. It was apparent that the Chinese treated the meeting between Rajiv Gandhi and Deng as a special gesture to the son of Indira Gandhi. They were not prepared to extend the same gesture to Rao.

The visit of Rajiv Gandhi to China in December,1988, was highly successful and marked the culmination of the process of normalization of the diplomatic relations between the two countries”¦On his return to India, Rajiv Gandhi had nothing but the highest praise for the role of the R&AW…

In a gesture to India at the time of the first Gulf war of 1991, when Chandra Shekhar was the Prime Minister with the support of the Rajiv Gandhi-led Congress (I), Chinese intelligence officials through the R&AW’s liaison representative in Beijing offered to recommend to their leadership the supply of oil to India to enable it to meet any shortages it might face due to the war. The Government of India did not avail of the offer.

During the periodic meetings of the officers of the R&AW and the MSS in New Delhi and Beijing, R&AW officers used to raise without fail China’s nuclear, missile and military supply relationship with Pakistan and point out how this was standing in the way of the full flowering of the bilateral relations, but their standard reply was that they were supplying only defensive equipment to Pakistan which would not pose a threat to India and that they would be happy to consider any request from India for the supply of defensive equipment, which would not pose a threat to Pakistan.

Developments in South-East and East Asia, the US relations with Japan and China’s relations with Pakistan used to figure on the agenda of all these discussions. In addition, they would invariably ask for a briefing on the activities of the Dalai Lama and his followers from the Indian territory. Despite our repeated assurances that the Tibetans living in the Indian territory would not be allowed to pose a threat to China and to Chinese leaders visiting India, they continued to express concern over their presence and activities in the Indian territory. However, they did not allow this to come in the way of the development of the bilateral relations.

While the liaison relationship between the R&AW and the MSS thus continued to develop satisfactorily and made an important contribution to the success of Rajiv Gandhi’s visit to China, the R&AW’s reporting on China—particularly in respect of military intelligence— was frequently criticized by the Indian Army. The R&AW had only two main sources of military intelligence about China—its Western liaison contacts and the trans-border sources from Tibet. Both these sources tended to exaggerate the over-all Chinese military capability and military deployments in Tibet. The Military Intelligence repeatedly challenged the R&AW’s estimate of the Chinese military deployments in Tibet as inflated. After having refuted the MI’s challenge for a long time, the R&AW had to admit that its estimate needed to be revised downwards.

There was similar criticism from the MEA of its political coverage as based largely, if not totally, on open information. Not only the MEA, but even some liaison agencies expressed the view that the weekly reports of the R&AW were nothing but a collation of open information from the Chinese media. Some of the liaison agencies even asked the R&AW to discontinue sharing such open information since it was of no use to them. The analytical reports and assessments prepared by the R&AW also came in for criticism that they lacked depth and insights.

Only the R&AW’s reports on the state of the Chinese economy came in for high praise from the Ministry of Finance and the Planning Commission. Though these were also based largely on open information, they found the reports more analytical. Moreover, in the 1980s, when the Chinese leadership had started opening up its economy, the R&AW was the only agency or department of the Government of India, which was systematically monitoring economic developments in China.

Continuity with innovative change was Rajiv Gandhis contribution to the operational policies of the R&AW relating to Pakistan, Afghanistan and China. These policies had been laid down by Indira Gandhi.

The sizable increase in investments for improving the intelligence collection capabilities of the R&AW under Rajiv Gandhi did not produce the same beneficial results in respect of China as they did in respect of Pakistan. The R&AW’s post-1968 renowned experts on China such as G.S.Mishra, S.N.Warty, Deepankar Sanyal, N.Narasimhan, etc were all of IB vintage hand-picked and got trained by Mallik. He also got trained a number of excellent linguists in India itself, Hong Kong and China. They served the organization with great distinction. The last of the IB-trained experts retired in January,2003. The China experts produced by the R&AW after its formation in 1968 were good, but the general impression was that they were not comparable to those of the IB vintage.

Unfortunately, human and material resources provided for strengthening the China expertise of the R&AW were not on par with those provided for the Pakistan division. The R&AW has had 16 chiefs since its formation in 1968. Of these, only one (N.Narasimhan—1991 to 93) could be described as a real China expert. This deficiency in respect of China continues. The Special Task Force for the Revamping of the Intelligence Apparatus set up by the Government of India in 2000 on the recommendation of the Kargil Review Committee (KRC) focused essentially on our intelligence capabilities relating to Pakistan and counter-terrorism. It also briefly dealt with economic intelligence and the security implications of the Internet. But, it paid inadequate attention to an examination of our intelligence collection and analysis capabilities with regard to China. It is time to have a comprehensive examination of our China-related inadequacies.

Continuity with innovative change was Rajiv Gandhi’s contribution to the operational policies of the R&AW relating to Pakistan, Afghanistan and China. These policies had been laid down by Indira Gandhi. After inheriting them, he imparted to them a vigour,a laser-sharp focus and a new dynamism, which they lacked before his taking-over as the Prime Minister. The biting power of the R&AW, which had weakened between 1977 and 1980, was restored. It once again became—as it was before 1977— an agency not only for the collection and analysis of intelligence, but also for the defence and enforcement of India’s national interests in its neighbourhood through covert non-diplomatic means, where diplomatic means were found inadequate or ineffective. While the covert action capability thus improved tremendously under Rajiv Gandhi, the improvement in its intelligence collection and analysis capability did not keep pace with the requirements of the nation and the time.

Rajiv Gandhi’s operational policy with regard to Sri Lanka was marked not by innovative change, but by bewildering confusion ultimately leading inexorably to his brutal assassination in May,1991, when he was the Leader of the Opposition. I call it his operational policy and not the R&AW’s policy because many of the twists and turns in the policy could not be attributed to a single agency of the Government of India. He was the source of much of the confusion, which came to charactetrize our operational policy. The way our operational policy with regard to Sri Lanka was mishandled by Rajiv Gandhi and his successor V.P.Singh has not been the subject of a detailed study in India. It was a typical example of how not to handle a sensitive operation.

As I had mentioned earlier, when Rajiv Gandhi took over as the Prime Minister, he was immediately convinced of the wisdom of the operational policies laid down by his mother in respect of Pakistan and Afghanistan. However, he was not clear in his mind about the policy of activism in support of the Sri Lankan Tamils laid down by her. This activism, which had initially remained secret, became public knowledge even when she was the Prime Minister when a well-known weekly of New Delhi came out with some of the alleged details of this covert activism.Some of these details were correct, but many wrong. Whatever might have been the merits of the policy of covert activism laid down by her, it must be said to her credit that she instinctively understood the importance of having a single nodal agency to pursue this covert option. And she had laid down two clear-cut objectives for this policy—- to make the Government of Sri Lanka responsive to the security concerns of India and to give the Sri Lankan Tamils a strong voice and a capability to find a negotiated political solution to their problems without the Government of India unduly getting involved in the process of finding a political solution.

Rajiv Gandhi, who was initially hesitant to pursue the policy of his mother, subsequently became—- for reasons which I was never able to understand—an over-enthusiastic follower of the policy.In his pursuit of the policy, he brought about changes which proved counter-productive and ultimately led to confusion and disaster. For the implementation of her operational policy, Indira Gandhi almost totally relied on the R&AW and on a triumvirate consisting of Kao, Saxena and the late G.Parthasarathi. While carrying out her instructions, they sought to exercise some caution and moderation in her thinking and actions. She valued their advice and listened to them.

Future generations of R&AW officers should know and should be proud of the role of the R&AW in this. It shows what good the R&AW can do for the country if it gets the right guidance and encouragement from the political leadership of the country.

Under Rajiv Gandhi, there was not a single nodal agency. In his over-enthusiasm to implement his policy, he inducted a multiplicity of agencies and dramatis personae into the scene—- the R&AW, the IB, the Tamil Nadu Police, the Directorate-General of Military Intelligence (DGMI), the Army and the MEA. These agencies kept stepping on each other’s toes. There was an awful lack of co-ordination. The chiefs and senior officers of these agencies—instead of exercising caution and moderation in his thinking and actions— vied with one another in egging him on into more and more unwise actions. There was a total lack of coherence in policy-making. The Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC), which was supposed to bring about such coherence in thinking and actions, failed in its duty to do so.

The plethora of Sri Lankan Tamil organizations, which came into being with the benediction of the Government of India, pursued their own narrow partisan interests rather than the over-all interests of the Sri Lankan Tamils as a whole. They took full advantage of the lack of coherence and co-ordination in New Delhi to take assistance from a variety of sources inside and outside India in order to strengthen themselves not only against the Sinhalese, but also against each other.

They took money from the R&AW without the IB and the DGMI being aware of it. They took money from the IB without the R&AW and the DGMI being aware of it. They took money from the DGMI without the IB and the R&AW being aware of it. They took money from the discretionary grant of the MEA without any of the intelligence agencies being aware of it. They took money from the Tamil Nadu Police without the Government of India being aware of it. They took assistance from the Indian intelligence agencies. At the same time, they had no qualms over seeking and accepting assistance from foreign terrorist organizations such as Pakistan’s Harkat-ul-Mujahideen with the blessings of the ISI, the Hezbollah, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) of Yasser Arafat and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) of George Habash.

When Prabakaran, the leader of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), was disinclined to accept the Indo-Sri Lankan Agreement of 1987, which led to the induction of the Indian Peace-Keeping Force (IPKF) into the Tamil areas of Sri Lanka, Arafat sent a message to Rajiv Gandhi offering his good offices for making Prabakaran accept the agreement. After politely declining his offer, Rajiv Gandhi asked the intelligence agencies to check up how Arafat claimed to have some influence over Prabakaran. Their enquiries brought out that the LTTE was in secret touch with the PLO’s so-called diplomatic mission in Delhi without the knowledge of the Government of India and that senior PLO representatives used to visit Chennai secretly to meet LTTE leaders.

There was not only a multiplicity of agencies and Departments of the Government maintaining contacts with the different Sri Lankan Tamil groups, but there was also a multiplicity of privileged interlocutors holding secret talks with Prabakaran and other Tamil leaders on behalf of Rajiv Gandhi—with one not knowing what the other was doing. The decision to induct the IPKF into Sri Lanka to restore normalcy and to make the LTTE amenable to accepting what it viewed as a dictated peace seemed to have been taken without a proper assessment of the ground realities in the Tamil areas of Sri Lanka and the likely difficulties in carrying out counter-insurgency tasks in a foreign territory.The Indian Army seemed to have imagined that since it was familiar with counter-insurgency operations in different areas of the Indian territory, the operations in the Tamil areas of Sri Lanka should be no different. One was told that an over-confident and over-enthusiastic Gen.Sunderji, the then Chief of the Army Staff, told Rajiv Gandhi that the IPKF would be able to accomplish its mission within a month. When this did not happen and the IPKF got involved in a quagmire, he put the blame on the intelligence agencies—particularly on the R&AW— for not warning him in advance of the capabilities, strength and motivation of the LTTE. As a Lt.Gen., he did the same thing in 1984 when he was put in charge of the military operation against the Khalistani terrorists, who had occupied the Golden Temple in Amritsar. When the operation took a longer time than expected and became messy due to a fierce resistance put up by the terrorists, he blamed the intelligence agencies for not providing adequate intelligence about the capability of the terrorists inside the Temple.

While not a single agency or department of the Government of India had a complete picture of what was being done by various agencies and departments in relation to Sri Lanka, there was one agency outside India, which must have had a complete picture. That was the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). It was getting from the French external intelligence agency copies of all reports being sent to the PMO by the IB and the R&AW which the French agency was getting from its source in the office of the then Principal Secretary to the PM. It was also getting a large number of sensitive documents and information from the office of the R&AW in Chennai through its head, who was allegedly being run as a source by a CIA officer posted in the US Consulate at Chennai.

While not a single agency or department of the Government of India had a complete picture of what was being done by various agencies and departments in relation to Sri Lanka, there was one agency outside India, which must have had a complete picture. That was the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

The IB’s surveillance team, which used to take video-recordings of the movements and meetings of this CIA officer, once reportedly noticed in one of its video clips the local R&AW chief jogging along with the CIA officer on the Marina beach. Further enquiries gave cause for suspicion that this officer had been won over and recruited by the CIA. He was called to Delhi ostensibly to attend a meeting with the head of the R&AW without making him aware that he was under suspicion. On his arrival, he was taken into custody and interrogated by a joint team of counter-intelligence experts from the IB and the R&AW. He reportedly confessed and was detained in the Tihar jail in Delhi for a year under the National Security Act. One was told that Rajiv Gandhi was against jailing him, but Joshi, the then chief of the R&AW (1986-87), insisted on his being sent to jail in order to convey a firm warning to other officers not to fall a prey to the temptations offered by foreign intelligence agencies.

When Indira Gandhi was the Prime Minister, an IPS officer of the R&AW, who used to deal with Sri Lanka and who had made a name as an upright and religious-minded officer, approached Kao and requested him to have his name recommended by the R&AW for the Indian Police Medal. At Kao’s request, the R&AW did so. The procedure was that the R&AW used to send the recommendation to the MHA, which would put it up to the Prime Minister along with the personal file on the officer kept in the MHA. This personal file used to contain all papers on the work and conduct of the officer ever since he joined the IPS. The MHA did so.

After some days, the file came back from Indira Gandhi with the following note: “Please see the report in his personal file at Flag X. I am surprised that an officer with such a background should have been recommended for the Police Medal.” In the personal file was a report sent 20 years earlier by the Chief Secretary of the State of the officer to the Home Secretary of the Government of India.

In his report, the Chief Secretary had stated as follows: After joining the State, the officer had got engaged to a girl and taken a dowry of Rs.one lakh from her parents. Before the marriage, his parents started demanding more money as dowry.When the girl’s parents expressed their inability to pay more, the officer cancelled his engagement to the girl and refused to return the amount paid initially.

It was this officer who was subsequently recruited by the CIA. The inherent defect in his character, which was unnoticed by the R&AW, had apparently been noticed by the CIA and he was targeted for recruitment.

In fact, he and his parents denied having taken any amount. The girl’s parents sent a written complaint to the Chief Secretary, who ordered an enquiry. The enquiry could not find provable evidence against the officer. The Chief Secretary personally interviewed the girl and her parents. While forwarding the enquiry report to the Home Secretary, the Chief Secretary had remarked that while no evidence could be found against the officer, he had no reason to disbelieve the allegations of the girl and her parents.It was this officer who was subsequently recruited by the CIA. The inherent defect in his character, which was unnoticed by the R&AW, had apparently been noticed by the CIA and he was targeted for recruitment.

Possibly by unintended coincidence, even as the penetration of the R&AW’s office by the CIA through this IPS officer was detected after he had caused some damage, another officer joined the R&AW’s headquarters when Rajiv Gandhi was the Prime Minister and managed to ingratiate himself with the senior officers to such an extent that he was considered a blue-eyed operative of the organization. He claimed to have access to the documents of a division of the US State Department, which dealt with external economic assistance, through his sister, who was a US Government servant working in that Division. He managed to get from her copies of a number of classified reports of her Division relating to South Asia.

The R&AW was priding itself on the fact that it had succeeded in penetrating the US State Department through a mole. Years later, in 2004, it came out that this officer was a mole of the CIA in the R&AW. He must have been of even a greater value to the CIA than the head of the R&AW office in Chennai because it had him whisked out of India and gave him shelter in the US after he came under suspicion. To enable him to escape from India without being caught, it reportedly issued to him and his wife US passports under different names. This extraordinary action of the CIA, which amounted to its admitting that he was its mole, gave an idea of what should have been his value to the CIA. It apparently wanted to prevent at any cost his interrogation by the Indian counter-intelligence experts. Even at the risk of a serious misunderstanding with the Government of India, it helped him to flee to the US and settle down there. His name is Major Rabinder Singh.

Shortly before his arrival, a dummy improvised explosive device (IED) was found in a corner of the Control Room. The person, who planted it, apparently did not want to cause any explosion. At the same time, he wanted to show that he had access to the Control Room. Who was he an insider or an outsider? What was his identity? It could not be established.

Shortly after the exit of Rajiv Gandhi as the Prime Minister, there was another worrisome incident in the R&AW headquarters. A conference of the Directors-General of Police and the heads of the central police organizations on security-related issues was held in the conference hall of the R&AW. Among those, who attended the conference was K.P.S.Gill. Shortly before his arrival, a dummy improvised explosive device (IED) was found in a corner of the Control Room of the organization. It was dummy in the sense that it had been properly assembled, but there was no explosive charge in the cavity meant for it. The person, who planted it, apparently did not want to cause any explosion. At the same time, he wanted to show that he had access to the Control Room. Who was he—an insider or an outsider? What was his identity? It could not be established.

In 1996, the IB was reported to have detected a penetration of their organization at the headquarters by the CIA at a very senior level. In 2006, there were reports of the penetration of the National Security Council Secretariat (NSCS), which is part of the PMO, by the CIA. These detections show serious weaknesses in the counter-intelligence and internal security set-ups of the IB and the R&AW. The IB and the R&AW act as watch-dogs of the internal security set-ups in other Government departments—-the IB internally and the R&AW externally— but who is to act as an independent watch-dog of the counter-intelligence and internal security set-ups of the IB and the R&AW so that our policy-makers are assured that they are competent enough to prevent a penetration of their own offices by foreign intelligence agencies. It is time to pay attention to this, if this has not already been done.

There are two options. The first is to appoint an IB officer as the head of the Counter-intelligence and internal security set-up of the R&AW and vice versa. The second option is to emulate the CIA and some other foreign agencies and create a post of Inspector-General in the intelligence agencies to act as an independent watch-dog of the performance of the intelligence agencies and the state of their internal security and counter-intelligence. In the US, only officers known for their independence, objectivity and personal integrity are considered for appointment to this post. Their reports go directly to the Congressional Oversight Committees with copies to the head of the agency. In India, till we set up the system of parliamentary oversight of the intelligence agencies, his reports can go directly to the Prime Minister, with copies to the head of the agency.

Rajiv Gandhi enthusiastically shared his mother’s interest in Africa and ensured that the requests from the African countries for training and other assistance and from the ANC and the SWAPO for any assistance were met. By the time apartheid came to an end in South Africa and Namibia became independent, Rajiv Gandhi had lost the elections. After his release from decades of detention, one of the first countries visited by Nelson Mandela, the ANC leader, was India when V.P.Singh was the Prime Minister. At the celebrations to mark the independence of Namibia—-again when V.P.Singh was the Prime Minister— the Congress (I) delegation led by Rajiv Gandhi as the Leader of the Opposition was accorded greater honours by the Namibian authorities than the delegation of the Government of India. It was their way of expressing their gratitude to India, the Congress (I), Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi for what they did to help the anti-apartheid movement and for the independence of Nambia.

Future generations of R&AW officers should know and should be proud of the role of the R&AW in this. It shows what good the R&AW can do for the country if it gets the right guidance and encouragement from the political leadership of the country. The R&AW has immense potential for promoting the national interests of the country.It is for the political leadership to be aware of this potential, to nurse it and make full use of it. Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi did. The other Prime Ministers didn’t.

No other Prime Minister of India—-not even Indira Gandhi— took such an active interest as Rajiv Gandhi did in the IB and the R&AW and its officers and in encouraging initiatives to improve their working. Rajiv Gandhi computerized the working of the R&AW, made the officers at all levels become computer-literate and made the level of computer-literacy of an officer an important quality to be reflected in his Annual Confidential Reports. He initiated proposals for improving the conditions of service of intelligence officers while in service and their quality of life after their retirement, keeping in view the harsh and almost anonymous life led by them. Despite his being an active and powerful Prime Minister, he could not push his proposals through due to opposition from the IAS officers. One understands that some of these proposals for serving officers have since been implemented by Dr.Manmohan Singh, the present Prime Minister, on the advice of M.K.Narayanan, the National Security Adviser.

If I recall B RAMAN who was from the MP Cadre is no more. He passed away a few years ago. Why are you referring to him in the ‘Present’ tense.

THIS WAS ALSO THE PERIOD WHEN ISI TRIED TO CAUSE MUTINY IN RAW WHEREIN THEY RECRUITED A LOW LEVEL FUNCTIONARY, ONE RK YADAV. HE WAS FINALLY DISMISSED FROM SERVICE ALONG WITH OTHERS. THAT IS WHY THIS CHARACTER CONTINUES TO SPIT VENOM AGAINST RAMAN