Study of military history is never complete. New aspects come to light every time one reviews a campaign or war. Often, the tales of valour, camaraderie, and success draw attention away from the picture at strategic and operational levels. Therefore, a deliberate study of the higher direction of war, becomes essential.

This article aims to examine the conduct of all Indian wars, post independence, at macro level, focussing attention on the achievements at formation level only. Details of tactical battles are well covered in various books, hence are not discussed here. Conduct of internal conflicts, Op Pawan and Op Cactus are also not covered as these require separate in-depth analysis.

The Kargil War, though smaller than other wars, is discussed in some detail because it is the most recent, brings out many lessons, and also indicates whether the Forces have been learning from previous wars.

Indo Pak War of 1947-1948

Despite the Standstill Agreement signed between Pakistan and J&K, Pakistan planned the invasion of J&K as early as 20 August 19471.

At the time of Independence, the effectiveness of most units was low, due to transfer of manpower and officers. Yet, the Army fought well and saved a considerable portion of J&K, supported by the IAF. They could have liberated more, had the Government (read PM) desired. On the contrary, in July 1948 the Government issued orders, restricting offensive actions2.

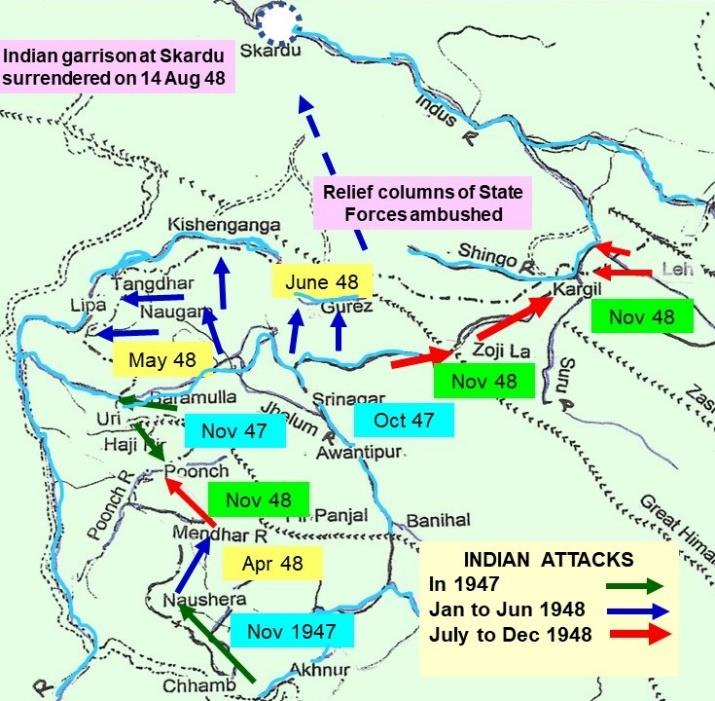

Indian Operations in 1947-48

Indian Operations in 1947-48

Since Skardu garrison (in Gilgit Baltistan) could not be resupplied by the IAF nor could it be reinforced by the State Forces relief columns that were sent, the garrison surrendered on 14 August 1948. Despite the order restricting offensive operations, the Army went on to save Mendhar, Poonch, Zojila, Kargil and Ladakh, in the last quarter of 1948, as shown on the map.

The UN resolution of 13 August 1948, calling for a ceasefire, was not accepted by Pakistan. Only when the Indian Army was on a winning spree in November, did Pakistan accept the ceasefire, which came into effect on 31 December 1948. In the war we lost 2,814 persons killed. A question often asked is: “could the Indian Army have achieved more”? Yes it could, had the Government so desired.

The Political leadership of Pakistan conducted the war far better than India. The Indian Government, in particular the PM, believed in peaceful resolution of differences and had great faith in the UN. These pacificthoughts must be appreciated, but in hindsight we realise these were not in the best interests of the Nation.

While the Pakistani Government fully exploited the expertise of stalwarts like Gen Sir Frank Messervy and Gen Gracey, the Indian Government kept the British Generals away from the war. It is astonishing that the C-in-C of a Nation did not contribute in the war. Then why were they appointed? But the worst decision of the PM was to halt offensive operations, even when the Nation was at war. This may well be a unique decision in the history of warfare worldwide! It is said that Shaikh Abdullah had a major say in this decision.

The China War in 1962

Throughout the 1950s, the politicians’ disdain of the Armed Forces impeded any modernization programme; but the greatest damage was by the defence minister, Shri Krishna Menon undermining the military chain of command. Unhappy with the minister, Gen KS Thimayya, COAS, resigned on 31 August 1959, but the PM persuaded him to withdraw his regnisation, which, as a upright soldier he did. However, the PM belittled him in the Parliament which was to affect the COAS’s functioning.

Mishandling of the border issue over many years soured relations between India and China. Assam Rifles and armed police commenced forward deployment,(the former under the aegis Ministry of Home in the East while the latter in the West under the Foreign Ministry)leading to clashes with the PLA in 1959. The Indian Army was then directed to deploy on the border and pursue a forward policy, which implied deploying in penny packets, disregarding tactical and logistic considerations. Gen Thimayya remained reluctant, but the policy was pursued vigorously by his successor, Gen Thapar and Lt Gen Kaul, the new CGS.

The clash forward of Namka Chu in Arunachal Pradesh, on 10 October 1962, followed by a report that the Indian PM had ‘ordered’the Army to throw the Chinese back was the last straw for the Chinese.

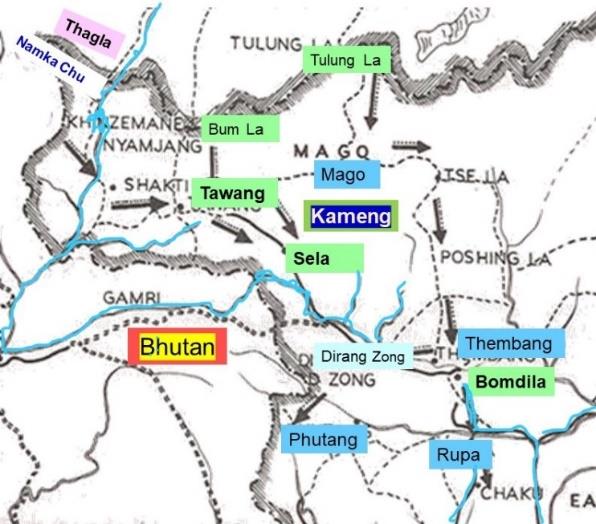

Kameng 1962

The PLA launched offensive operations on 20 October 1962 over the entire front and eliminated the isolated posts. 7 Infantry Brigade at Namka Chu ceased to exist. Indian formations redeployed in depth receiving reinforcements from the rear. Transport aircraft of the IAF kept the formations supplied.

Two additional brigades and an armoured regiment were moved to Kameng. Yet, when the Chinese advanced on 17 November, 4 Corps collapsed completely even with the COAS and the GOC-in-C Eastern Command present in the corps HQ at Tezpur.

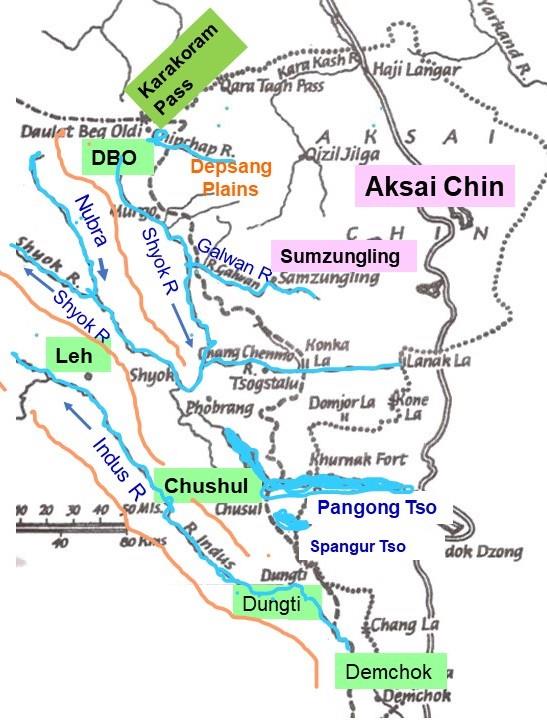

In Ladakh, one brigade was inducted and deployed to guard the Indus Valley, and two additional battalions were moved to Chushul. A troop of light tanks was airlifted to Chushul . The PLA captured two forward company positions by 18 November.

East Ladakh 1962

At this stage, although IAF combat aircraft had not been used in the war, Pandit Nehru requested President Kennedy to deploy 15 squadrons of USAF to attack the Chinese3. The request was not accepted. However, a great deal of military equipment and extreme cold area clothing was flown in from many countries.

There was panic in Delhi. The Government ordered a ‘scorched earth’ policy, to destroy maximum assets before withdrawing from Assam4; fortunately, the Chinese declared a unilateral ceasefire on 20 November, and withdrew to positions 20 km behind the 1959 line, asking India to do the same. The Indian Army lost 3,175 bravehearts.

The fairly successful conduct of defence in Ladakh was eclipsed by the debacle in 4 Corps. To ward off criticism, the PM found it expedient to explain the setback as treachery by China and inability of the Indian Army to guard the borders. Books written about the conflict were banned for many years, and the Henderson Brooks Report on this war is still classified.

At the Government level, the planning and conduct of affairs with China was pathetic. A question that begs an answer is, was the war necessary? Though India propagated Panchsheel, the Government did not practise it when the need arose. Instead of negotiating at the diplomatic level, the Government adopted a collision course which was bound to lead to war. By its actions, the Indian government presented China with not only a grand military victory but also a moral victory, with China declaring a unilateral ceasefire and vacating areas overrun during the war.

Further, by blaming China for deceit, the Indian Government saddled the Nation with a lasting problem, which will continue to drain our precious resources for many more decades. No Government can now renegotiate the issue or make concessions without political fallout at home.

Indo Pak War of 1965

After the 1962 Conflict, there was rapid expansion of the Indian armed forces. Pakistan too received Patton tanks and modern aircraft from the USA. This encouraged the Pakistani President to make a second attempt to seize J&K by force. Major events of 1965 are given below.

In February, tension increased in the Rann of Kutch. Pakistan moved one division and one squadron of F 86 Sabres, to the sector, where the Indian Army had one infantry brigade. 50 Para Brigade was inducted and both brigades placed under a newly raised Headquarters Kilo Sector. The terrain favoured Pakistan, which gained an upper hand in the skirmishes that followed. Why the disadvantages of terrain were disregarded by the Indian commanders, is not recorded. The alignment of the border was later delineated by an international tribunal5.

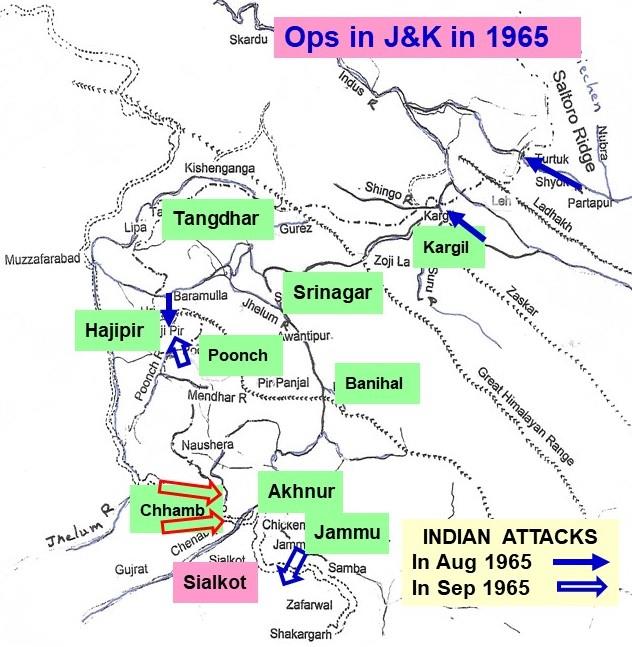

Thereafter, suddenly on 05 August 1965, Pakistan infiltrated Mujahids to create mayhem in J&K, and to incite the population to revolt. The operation, called Op Gibraltar, was decisively defeated by the Indian Army which also captured important heights in Kargil and Hajipir. IAF helicopters assisted the Army.

Ops in J&K in 1965

Thereafter, Pakistan launched Op Grand Slam on 01 September 1965, to capture Akhnur. IAF commenced operations over Chhamb, on the same day, but the Pakistanis continued to advance. After discussion with his cabinet on 03 September, the PM directed the Army and IAF Chiefs to defeat Pakistani attempts to seize Kashmir by force, destroy Pakistan’s offensive power, and to occupy Pakistani territory which would be vacated after the war.

Accordingly, commencing on the night 05/06 September, the Brigade at Poonch linked up with 68 Brigade at Hajipir. Early morning on 06 September, 11 Corps launched Op Riddle, to advance to the Ichhogil Canal, on a broad front. Two days later 1 Corps advanced towards Pasrur.

Though the air war had commenced over Chhamb on 01 September, Op Riddle was launched without air cover or air support6. Despite this, the divisions progressed and one battalion even crossed the IchhogilCanal to threaten Lahore. Pakistan halted the Chhamb offensive and redeployed forces south of Chenab River.

Air war commenced in full measure, on 06 September evening when PAF attacked several airbases7. 4 Infantry Division (this Division had been deployed in the Tawang Sector in 1962) of 11 Corps, occupied defences at Asal Uttar east of Khem Karan along with 3 Cav and 9 Horse. On 10 September, Pakistan launched her 1 Armoured Division in this sector. The Pakistani armoured division was mauled and forced to withdraw leaving 97 tanks, but 11 Corps could neither launch a riposte nor recapture Khem Karan during the war, despite receiving two additional brigades. After 10 September, all formations captured small areas but suffered heavy casualties since the Pakistanis had reinforced their positions. The Corps had seven armoured regiments8 but these were used peicemeal mainly for fire support.

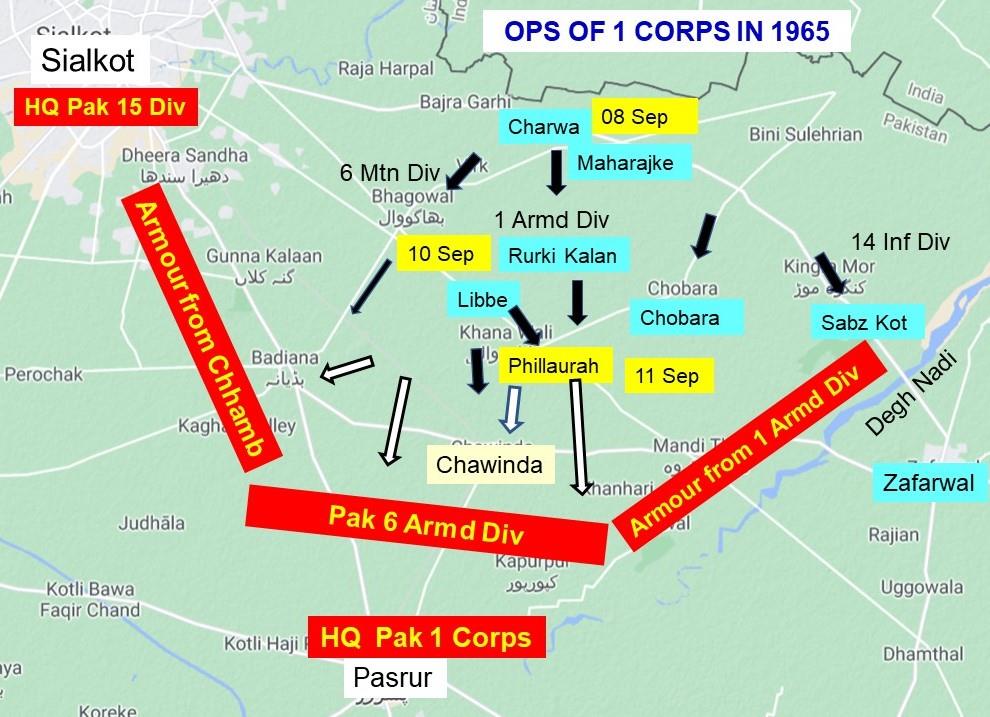

On 08 September 1965, Indian 1 Armoured Division, part of 1 Corps, advanced towards Sialkot but it was so slow that Pakistan deployed its 6 Armoured Division, even before the Indian armour could advance 10 km9. The Pakistanis reinforced the sector with armour sidestepped from Chhamb and from Pakistani 1 Armoured Division. As a result, there were heavy casualties with limited gains. Yet, 1 Corps retained the initiative and the war was kept on Pak territory.

1 Corps in Sialkot Sector in 1965

The IAF had 30 squadrons of combat aircraft of which 16 had modern aircraft, the other 14 had vintage planes. The high-performance aircraft were used mostly for air defence of the airbases and for escort of missions. Against them PAF had 11 squadrons, all of modern aircraft. Of these, one squadron was in East Pakistan. The IAF conducted operations in the West and in the East. Strangely though, the air war in the East was initiated by Central Air Command, on its own10. In the retaliatory air strikes by the PAF squadron, IAF lost 12 aircraft. The PAF Squadron too lost 6 Sabres. This highlights the need for joint planning, and to conduct operations to achieve an overall aim. Resources must not be frittered away, just because they are available.

The war also brought out the need to modernise. Pakistan had better tanks and aircraft, which gave them a distinct advantage, although their inability to handle the Patton tanks led to disaster.

The Indian Naval Chief’s earnest request to participate in the war, had been turned down due to their state of equipment, but the Navy safeguarded the coasts and maritime assets during the war, which ended on 23 September. Our fatal casualties were 3,375.

Mediated by the USSR, the Pakistani President and the Indian PM met at Tashkent, where an agreement was signed to return all captured territories.

At the political level, Indian handling of the war was far better than before. However, despite Pakistan committing unprovoked aggression, the Indian Government remained satisfied with restoration of status quo ante. Also, after the war, the PM was criticised for returning territory of strategic value to Pakistan, but whether the Army Chief advised the PM before the Tashkent Meet, is not known.

Overall the senior leadership in the Army and the IAF was found wanting in many ways. With obvious disadvantages of terrain, the Generals should have avoided fighting in the Rann of Kutch. If India had to accept the decision of an international tribunal eventually, this could have been done without fighting a losing war first.

Also, examination of the second half of the 22 Day war reveals that most formations fought small nibbling actions after 11 September but suffered heavy casualties. The question arises, would it not have been better to reorganise and plan two major attacks with say one division and one armoured brigade each at Chhamb and Khem Karan, with maximum support by the IAF? not only would the casualties have been fewer, the pay offs would have been tremendous.

Discord in senior ranks, within the Army and with the IAF, as well as ineptitude of many senior officers in the two services, limited military gains.

Indo Pak War of 1971

In the General Elections held in Pakistan in December 1970, though the Awami League won an absolute majority the Pakistani leaders refused to hand over power to the party. To control the agitations that erupted in their Eastern province, General Yahya Khan deployed the Pakistan Army, whose genocide forced 10 million people to flee across the border. Indian appeals to Pakistan and to world powers, to stop the genocide, fell on deaf ears.

India signed a treaty of peace and friendship with USSR. The Armed Forces prepared for war, though the PM directed that India would not initiate war. They also extended support to the freedom fighters.

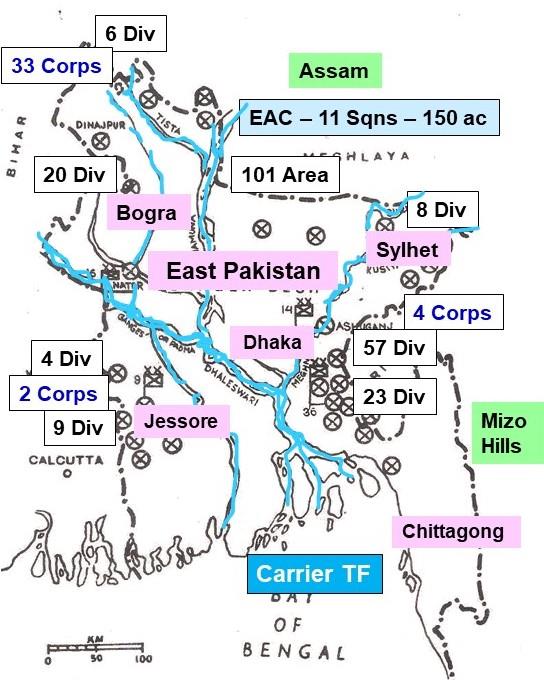

Liberation of Bangladesh in 1971

On 03 December 1971, PAF attacked Indian airbases in the west, followed by a few ground offensives by their Army.

The Eastern Fleet of the Indian Navy blockaded East Pakistan and struck the coastal areas. IAF gained air supremacy within two days. Eight divisions of the Indian Army, assisted by the Mukti Bahini advanced, bypassing strong opposition, and soon closed in on Dhaka.

On 16 December, Lt Gen JS Aurora accepted the unconditional surrender of all Pakistani forces in the East, accepting 93,000 prisoners. Dhaka was now the free capital of a new Nation!

In this campaign, it is surprising to find limited use of heliborne operations; although the IAF had 80 utility helicopters11 only 12 were used. Eastern Command had a Para brigade of which just one battalion was employed for an airborne assault though the conditions were ideal for more extensive use of heliborne troops.

War on the Western Front was far more challenging as the land and Naval forces were evenly matched, whereas the IAF enjoyed a superiority of 45:20 combat aircraft.

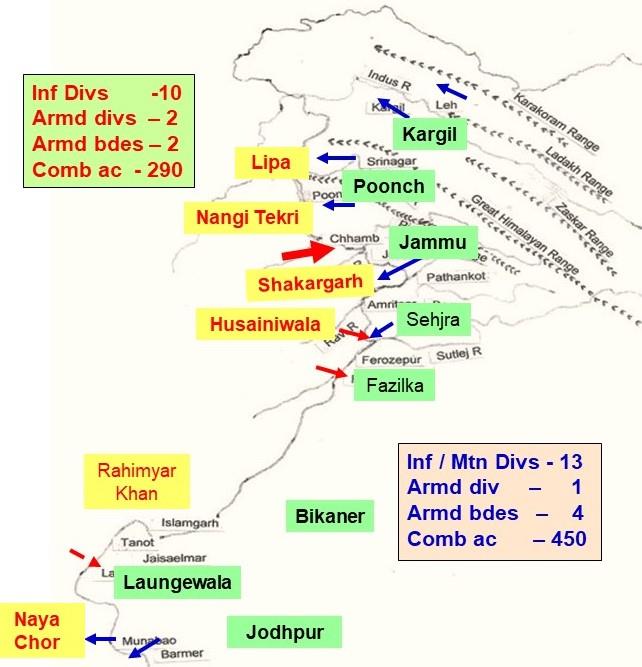

On the breakout of war, Indian 15 Corps captured important heights in high altitude and successfully defended Poonch. A strong offensive by the Pakistan Army, fully supported by the PAF, captured Chhamb, which was a major loss.

Strategic Defence on the Western Front in 1971

In the plains, 1 Corps kept the war on Pak territory in the Shakargarh Bulge, thus safeguarding the vulnerable highway to J&K. There were gains and losses in Punjab, where the Pakistanis captured Husainiwala and some area in Fazilka.

Though the Indian 11 Corps captured DBN and the Sehjra salient, which is north of Husainiwala, it did not attempt to recapture the latter. Nor could it clear the intrusion in Fazilka.

In the desert, 11 Division made steady progress fully supported by the IAF. 12 Division’s offensive plan was scuttled by the Pakistani 18 Division launching an armoured thrust towards Longewala, albeit without air support. As a result, IAF Hunters at Jaisalmer destroyed the Pakistani armour and vehicles, unhindered by the PAF.

The Indian Western Fleet dominated the Arabian Sea, denying its use to the Pakistanis. Two attacks on Karachi, by both, the Navy and the IAF, caused considerable destruction and forced the Pakistani ships to stay in harbour. The IAF carried out Maritime reconnaissance and provided air cover to the fleet. The Navy safeguarded offshore and on shore assets and kept the Indian merchant ships safe.

During the war, we lost approximately 3,836 soldiers killed. Western Command succeeded in its task of strategic defence, except in Chhamb, Husainiwala and Fazilka. Western Command had adequate time and resources to recapture all its territories, but it was not done. The air support was better than in the previous wars but still far from satisfactory. On one occasion the PM herself had to ask the Chief of Air Staff to provide more support to the Army12.

A great deal of Indian air effort was spent on attacking ground targets in depth, ostensibly in support of land battles. Had the Army formations been consulted, this effort would have been more useful. The effectiveness of counter air operations remained a moot point since the Army Commander continued to expect Pakistan to launch its 2 Corps in South Punjab, which implied that he considered the air situation favourable to Pakistan. Whether this was an error of judgement or excessive caution, is a matter of opinion, but PAF did execute attacks in Indian territory, till the last day. Better synergy and trust would have helped, but in the event, powerful reserves were kept idle and opportunities to annihilate the enemy, were lost. Indian political leadership may have been under international pressure which was generated when the fall of Dacca was eminent resulting in curbing further offensive military in this theatre.

At the politico military level, the key players deserve full credit for their part in the 1971 War. Both political and diplomatic actions were sound and timely. The PM’s firm stand against the US President was acknowledged by the New York Times on 18 December 1971, when they reported: “one major casualty of the War has been American Prestige”, when India completely ignored the approach of the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, USS Enterprise, into the Bay of Bengal.

At the military level there was greater synergy in the East than in the West. At Delhi better relations between the senior officers and with the RM would have furthered National interests.

One hears criticism about the return of 93,000 prisoners of war without seeking a permanent solution to J&K. This needs deeper examination against the provisions in the Geneva Conventions regarding prisoners of war. As it is, the prisoners and some families were held in India for well over two years after the war was over. Why the prisoners were held for so long, is not known.

Kargil 1999

After the elections in J&K in 1996, normalcy was returning to the State gradually under an elected government. This did not suit Pakistan whose new Army Chief decided to up the ante. Taking advantage of the ineffective surveillance grid of the Line of Control (LC)north of Zojila, Pakistan infiltrated specially trained Northern Light Infantry (NLI) troops to interdict the highway from Zojila to Kargil, and to occupy some additional area across the LC. Pak soldiers were well armed and well supported.

Indian commanders took time to grasp the magnitude of the incursions. A blame game commenced and panic in the minds of senior officers led to hasty, ill-planned attacks and unnecessary casualties. Notably, the three Services planned separate operations, Op Vijay, Op Safed Sagar and Op Talwar.

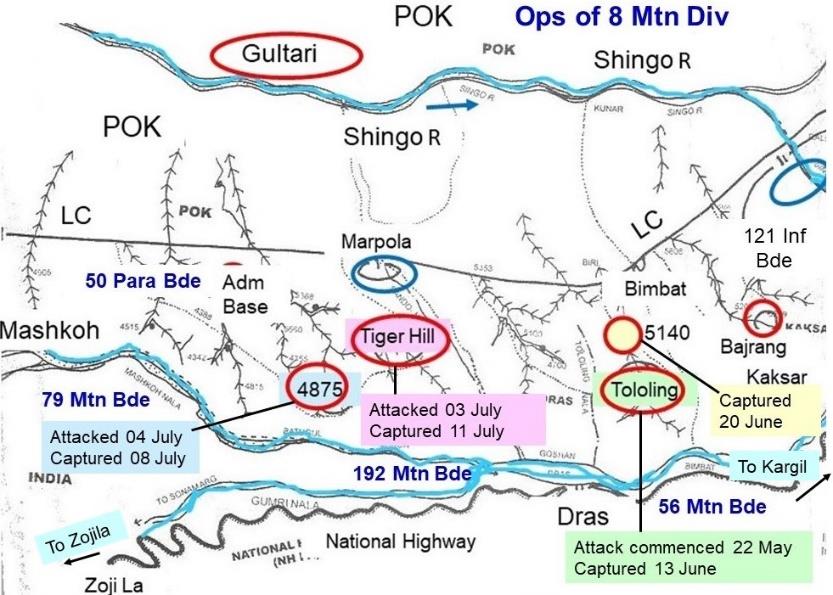

6 Mountain Division was trained for such an eventuality and was moved to J&K, but for some reason it was not employed. Instead, 8 Mountain Division was moved from the Kashmir Valley to Dras by 01 June 1999. After adequate recce and preparations, they commenced attacks on 12 June and recaptured the heights overlooking the National Highway, by 11 July 1999. 50 Para Brigade then cleared the area up to the LC; see map.

Dras Sector 1999

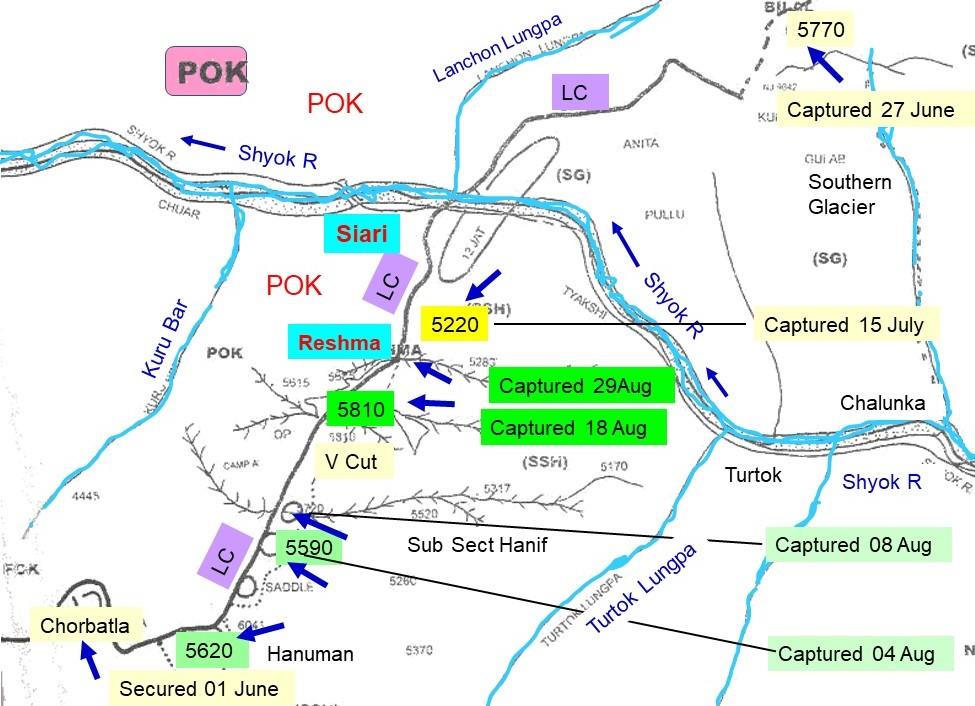

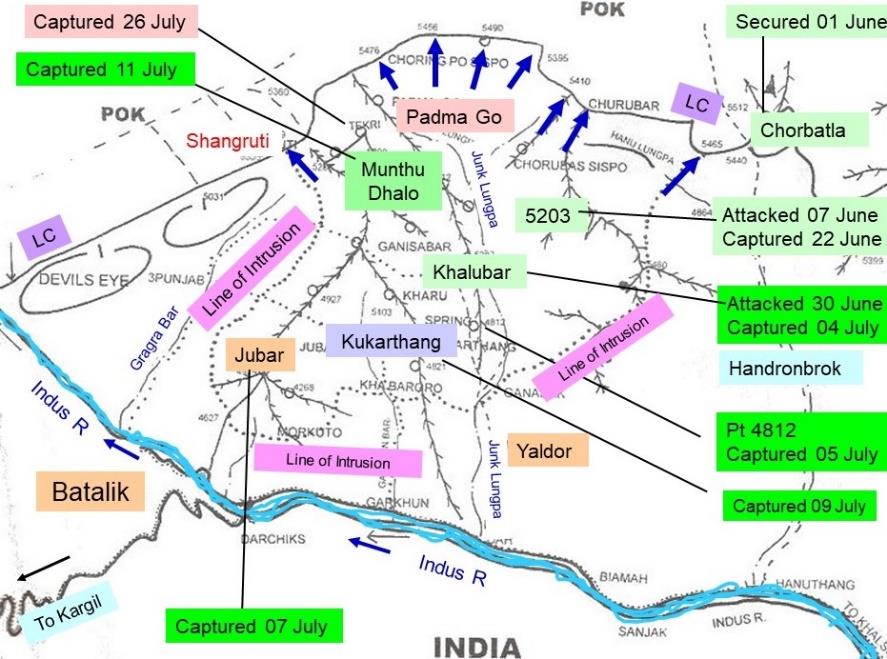

Meanwhile, 3 Infantry Division cleared the Batalik sector, followed by heights in Turtok sector (Sub Sector Hanif or SSH) in August. Trained personnel from HAWS (High Altitude Warfare School) assisted all formations. All attacks were multi directional, making best use of terrain. Skilled mountaineers executed cliff assaults wherever possible, to achieve surprise. Attempts were made to get behind the enemy positions wherever space permitted, but these were not successful, particularly in the Dras Sector.

Sub Sector Hanif 1999

Artillery provided effective support. 20 fire units were deployed in Dras and 15 in Batalik. While GOC 8 Mountain Division ensured fire support of minimum 18 fire units for each attack, in other sectors, some battalions had to attack with just two to four fire units13, which reflects on the formation commanders and artillery advisers. The system of ‘direct – indirect’ fire was applied in Dras with the Bofors guns firing direct and the fire being corrected by forward observation officers.

Batalik Sector 1999

The IAF took time to deploy and commence attacks. The delay enabled the Pakistanis to strengthen their defences even during May, which increased the difficulties for the ground attacks. The loss of two fighter aircraft and one helicopter by shoulder fired Surface to Air Missiles (SAMs), necessitated flying high, which affected accuracy14. Even the designators of the precision guided munitions (PGMs), had to be flown high, reducing accuracy. Pakistani gun areas and administrative bases were ideal targets for Air, but most of these remained beyond limits due to restrictions on crossing the LC, which was a government decision. Thus, despite skilful flying by the brave pilots , the IAF strikes were not effective on the peaks and razor-sharp ridges, though the psychological effect of air strikes was tremendous.

The rest of the Army, Navy and IAF deployed for possible escalation. The MEA (Ministry of External Affairs) explained our case abroad and swung international opinion in our favour. The combined effect of all these actions forced the Pakistani Government to withdraw their soldiers.

The Kargil war was conducted well by the Government. Questions have been raised about the decision not to cross the LC but that could have led to all-out war. This needs a debate keeping in mind all relevant factors that existed in mid-1999.

There has been discussion about responsibility for lackadaisical surveillance of the LC, which encouraged Pakistanis to plan the intrusions. There is unanimity of thought that all commanders in the chain of command were responsible in different measure but the fact is that no senior officer accepted moral responsibility.

Reflections and Recommendations

An overview of the wars indicates that the Indian Armed Forces have largely acquitted themselves well. The political direction of war was atrocious to begin with but picked up after 1962 and has not been found wanting thereafter. The strength of the Army has been its young officers, always and every time; but one does not hear the same comment about senior officers.

Although, compared to the American, British or Pakistanis, our Generals are much better, some of them have drawn adverse comments after operations. After Op Pawan the criticism was particularly severe (though this operation is not examined in this article). Therefore introspection is advisable.

In wars, professional competence of the Generals has been just satisfactory. Though they are masters in Operational Art in peace time, nowhere do we find this practised in war. Due to this lacuna, the Army has had to engage in many tactical battles that were unnecessary; capture at great human cost, objectives which had little importance; and fight under conditions of significant disadvantage. The political conservativeness results in a reactive defensive strategy which in turn constrains operational level operations. The statement, “We will fight with what we have” actually translates to the lack of political will to modernise the armed forces and employ hard power in securing and furthering national interests.

Be it in peace or during war, adversity has always led to panic followed by paralysis, from which senior officers take time to recover. Functioning in the ‘grey zone’ or the fog of war, the Generals have remained too confused to reorganise and utilise all their resources to advantage. There is a need to increase interoperability of formations to make these more versatile for employment in different environments and to facilitate multi-tasking for various contingencies.

This will also bring about considerable saving, which can be used for modernisation.

Another major lacuna has been little concern to minimise casualties. To recapitulate, number of fatal casualties in various wars have been, 2,814 in 1947-48; 3,175 in 1962; 3,375 in 1965; 3,836 in 1971 and 667 in 1999. These could be contrasted with Israeli casualties in three major wars in 1956 (231); 1967 (776); and in 1973 (2656). The Americans lost 149 soldiers in the Gulf War of 1991 though total casualties were 294.

We announce proudly that our young officers suffer disproportionately high casualties in wars; but then fail to do anything about it. Young officers are not cannon fodder! The Generals need to learn to execute tasks with fewer casualties.

Lack of synergy between the Services has resulted in limiting military gains in every war. The inability to work together is an undesirable weakness in senior officers and must be addressed. Similarly, senior officers must learn to function better with civil officials and political leaders, without compromising the interests of the Services.

A question arises: why do excellent officers, who make good COs, then go on to become mediocre senior officers? The excellence of the young officers indicates that the selection process and initial training are apt, but thereafter, the system develops leaders for peace, and not for war. In other words the officers have the potential to excel but the system encourages and promotes mediocrity. This deserves greater analysis, that is not possible in a review article, such as this one.

The Indian Nation is justifiably proud of its Indian armed forces, which enjoy the finest reputation in the world. it is up to the senior officers to carry out regular introspection to identify and eradicate weaknesses that creep into all organisations inevitably.

Notes

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Pakistani_War_of_1947–1948

- https://www.logically.ai/factchecks/library/dd11d968

- Neville Maxwell, India’s China War, Natraj Publisher, Dehradun, 1970, p 410

- Ibid, p 413

- SN Prasad and UP Thapliyal, The India-Pakistan War of 1965, p 23 to 38.

- ibid, p 151, 180.

- ibid, p 243

- In 1965, 11 Corps had seven armoured regiments and one motorised infantry battalion, excluding 61 Cav (horsed). These were 1 Horse, 3 Cav, 7 Lt Cav, 8 Lt Cav, 9 Horse, 14 Horse and CIH.

- Prasad and Thapliyal, p 190, Op Nepal.

- Ibid, pp 250, 251.

- SN Prasad and UP Thapliyal, The India – Pakistan War of 1971, p 206.

- ACM PC Lal, My Years with the IAF, Lancer Publication, New Delhi, 1986, pp 232 to 234

- Lt Gen YM Bammi, Kargil, the Impregnable Conquered, Gorkha Publishers, New Delhi, 2002, p 378, p 314 for 1 BIHAR two fire units, p 368 for 11 RAJRIF 4 fire units in Turtok Sector

- ibid, p 450

Fighting the war is the military’s job, but securing our rights after the war is the duty of the political and diplomatic machinery. As brought out by the author, India failed to press home the advantage which its military achieved.

The worst decision of 1948 was to halt offensive operations, when the Indian Army was better positioned to go all out to capture entire J&K. It must have been the aspirations of then PM Jawaharlal Nehru to play to the UN gallery to be a messiah of peace. Nehru again goofed it up with his Panchsheel in 1962.

Post 1965 war, it appeared that the Russians arm twisted Shastri to accept a peace deal brokered by them, resulting in India handing over most of the captured territories – including the most strategic Haji Pir pass.

Post 1971, Indian diplomats and politicians failed in securing a well defined deal when India had 93,000 prisoners of war.

Very well written article giving an abridged overview of Indian wars post independence, highlighting various shortcomings in planning and execution of operations at the macro level. Maps, particularly of the Western theatre, are illustrative and help understanding the progress of operations at a glance

A very well researched Article given iin a brief and concise manner. Simple language without jargon even to understand by non-military Personnel.. Lot of lessons have been brought out which need action by Politico Military heirarchy. Well done Gen KK Khanna.

5 Star Article.

Very well analysed and lessons at the strategic level brought out candidly. Let’s hope the senior leadership go in for a frank introspection to bring about more operational professionalism in services

Sir,

Wonderfully written article. Great learning for us. Thanks and Regards.

Wonderfully written article, well thought out and analysed. Unfortunately we haven’t even now not learnt our lessons. Still committing the same errors and hiding our shortcomings. There is no national policy. Strange but sad. Thanks and regards Gen Khanna. God bless

Exceptionally well written article with Extremely authentic information.

The narration of every war post independence is not only described in a vivid manner but in most military like manner.Truly a great pleasure reading the Article.