Background

Italy had joined the Second World War on 10 June 1940. Benito Mussolini, the Fascist dictator of Italy (Il Deuce-The Leader) appreciated that it was an ideal time to conquer the littoral area around the Mediterranean. Germany had overrun France during May-June 1940, and was in control of Western Europe. Thereafter, the Luftwaffe launched the air-offensive on Britain during August to October 1940 period, but contrary to expectations it did not succeed in wiping out the RAF. The heavy German losses in air assets (1977 attack aircrafts & 3510 trained aircrew) negated German plans for the envisaged follow-up amphibious invasion of England. The British stamped their supremacy at sea in the North Atlantic by hunting down and sinking the German capital ships Graf Spee and Bismarck. The German Navy then started the crippling U-boat campaign on the cross Atlantic supply convoys to England, which lasted for over three years.

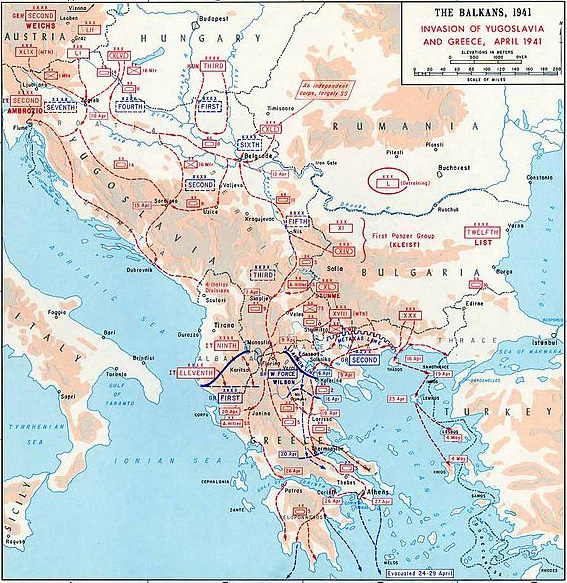

After Germany had invaded and annexed Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Fascist Italy attacked and annexed tiny Albania in April 1939 to bolster national prestige. The Italians further invaded Greece from Albania in end October 1940, but the Greeks put up a stout defence and repelled the invasion by February 1941, capturing considerable stretches of Albanian border territory. The Italians suffered combat losses of 89,696 personnel and 12,368 ‘frostbite’ cases. Coupled with the setbacks against British Commonwealth forces in North Africa, Il Duce’s regime in Italy had become very unpopular; and was seen as tottering in the eyes of the Fuhrer in Berlin. Further concern was caused by the buildup of the RAF in Greece following the Italian invasion. The British were able to mount upto 50 offensive sorties per day by February 1941, using 80 odd aircraft. In hindsight it can be said that the Italians had blundered by not capturing Malta after joining the War. The Germans were worried that the British Blenheim and Wellington bombers would subsequently mount an attack on the vital Ploesti oilfields in Rumania. So Hitler promised territorial gains, and pressurised Hungary (20 November 1940), Rumania (23 November 1940), and Bulgaria (1 March 1941) to join the Axis Camp. Yugoslavia followed (25 March 1941), as Regent Prince Paul wanted to stave off a German invasion. This decision was deeply unpopular in Serbia. Elements within the Yugoslav Army which was mainly officered by Serbians, engineered a coup de tat on 27 March 1941 and repudiated this capitulation. As a pressure tactic and contingency plan, Hitler had already moved sufficient forces into Rumania, Hungary and Bulgaria by April 1941. On 3 April 1941, Fuhrer issued Directive No. 26, ordering the invasion of Yugoslavia. Actual military invasion commenced on 6th April 1941 and Yugoslavia surrendered on 18 April 1941. Hitler had already made up his mind to invade Greece, after it had allowed British forces to be stationed at the islands of Lemnos and Crete. The German Wehrmat (Armed Forces High Command) issued Directive No. 20 on 13 December 1940, for “OPERATION MARITA”. This invasion also commenced from Bulgaria on 6 April 1941 through Southern Yugoslavia, and entered Greece proper on 8/10 April 1941. Mainland Greece was overrun by 30 April 1940!

Yugoslav Armed Forces

The Yugoslav forces when fully mobilised, consisted of 33 Divisions of the Royal Yugoslav Army (VKJ), four Air Brigades of the Royal Yugoslav Air Force (VVKJ) having about 400 aircrafts, and the small Royal Yugoslav Navy (KJRM) centred around four destroyers and two submarines based on the Adriatic coast. The VKJ was heavily reliant on animal-powered transport, and had only 50 modern tanks. The VVKJ was equipped with a range of aircraft of Yugoslav, German, Italian, French and British design, including 120 modern fighter aircrafts.

Equipment and Organization

The VKJ was equipped with weapons and material from WW I era, although some modernization with Czech equipment and vehicles had begun. About 1,700 artillery pieces were relatively modern. The modern mechanized units consisted of six motorized infantry battalions, six motorized artillery regiments, one tank battalion equipped with 54 modern French Renault R-35 tanks, plus an Independent Tank Company with eight Czech SI-D tank destroyers distributed in the three Cavalry Divisions. Some 1,000 trucks for military purposes had been imported from the USA in the months preceding the invasion. Of the permanently embodied Independent Regiments, 16 were in frontier fortifications and 19 were organized as Combined Regiments or ‘Odreds’, around the size of an Independent Reinforced Brigade. The Yugoslavs had delayed full mobilisation until 3 April, in order not to provoke Hitler. The German attack caught the Yugoslav Army still mobilizing, with only 11 divisions in their planned defensive positions. The Yugoslav Air Force (VVKJ)’s main aircraft types in operational use included 73 Messerschmitt Bf-109Es, 47 Hawker Hurricane-Is, and 30 Hawker Fury-IIs; plus 69 Dornier Do-17Ks, 61 Bristol Blenheim-Is and 40 Savoia Marchetti SM-79K bombers. Naval Aviation units had 12 German-built Dornier Do-22Ks and 15 indigenous Rogozarski SIM-XIV-H float-planes. The aircrafts of the Yugoslav-airline Aeroput, consisting of six Lockheed Model 10 Electras, three Spartan Cruisers, and one de Havilland Dragon provided transport services to the VVKJ. The Yugoslav Navy (KJRM) was equipped with one modern destroyer of British design, three modern destroyers of French design, two British-built submarines, 6 modern motor torpedo boats (MTBs), and six mine-layers.

Deployment

The Yugoslav Army was organized into three Army Groups and the Coastal Defense troops. The 3rd Army Group was the strongest with the 3rd, 5th and 6th Armies & the 3rd Territorial Army, defending the borders with Romania, Bulgaria and Albania. The 2nd Army Group with the 1st and 2nd Armies, defended the region between the ‘Iron Gates’ and the Drava River. The 1st Army Group with the 4th and 7th Armies, composed mainly of Croatian troops was in Croatia and Slovenia defending the Italian, Austrian (now German) and Hungarian frontiers. The strength of each “Army” amounted to that of a regular Army Corps, with their deployment as follows:

- 3rd Army Group’s 3rd Army had four Infantry Divisions and one Cavalry Odred; the 3rd Territorial Army had three Infantry Divisions; the 5th Army had four Infantry Divisions, one Cavalry Division and two Odreds; the 6th Army had three Infantry Divisions and five Odreds.

- 2nd Army Group’s 1st Army had one Infantry and one Cavalry Divisions, three Odreds and six Frontier Defence Regiments (FDR); the 2nd Army had three Infantry Divisions and one FDR.

- 1st Army Group consisted of the 4th Army, with three Infantry Divisions and one Odred; the 7th Army had two Infantry Divisions, one Cavalry Division, five Odreds, and nine FDRs.

- The Supreme Command Reserve was located in Bosnia and comprised four Infantry Divisions, four (I) Regiments and one tank battalion.

- Coastal Defence Force on the Adriatic comprised one Infantry Division and two Odreds, in addition to fortress brigades located at the Naval Bases of Šibenik and Kotor.

On the eve of invasion, proper clothing and footwear were available for only two-thirds of the front-line troops, and some of the essential supplies were in short supply. The Yugoslav Army also suffered badly from the Serbo-Croat schism in Yugoslav politics. Of the 165 generals in the Yugoslav, all but four were Serbs! Therefore the others did not feel motivated. Effective opposition to the German invasion was mainly displayed by Serbian Units.

Axis Order of Battle

The German invasion was spearheaded from the north by General Maximilian von Weichs’ 2nd Army with von Kleist’s 1st Panzer Group, and the SS 51 Panzer Corps; combined with overwhelming Luftwaffe support. After the unexpected coup d’état in Yugoslavia on 27 March, the objective of the 1st Panzer Group of 12th Army was changed to invading Yugoslavia, and capturing Zagreb. The 19 German divisions allotted for the Invasion of Yugoslavia included five Panzer Divisions, two Motorised Infantry Divisions and two Mountain Divisions. The German force also included – three well-equipped independent Motorised Infantry Regiments (Brigade-plus Groups), and was supported by over 750 aircraft. The Italian 2nd Army and 9th Army later joined in, and committed another 22 divisions and 666 aircraft. The Hungarian 3rd Army also later participated, with support from over 100 aircraft. Germany attacked Yugoslavia from bases in three countries besides itself: Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria.

German Deployment in Romania

King Carol II of Romania (who was of German descent), starting from the forced cession of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union, proposed in a letter to Adolf Hitler on 2 July 1940, that Germany send a Military Mission to Romania. The Romanian government on 7 September 1940 again asked that a Contingent be sent urgently, the day after Carol’s abdication. The decision to aid Romania was taken by Hitler on 19 September, and Hungary was asked to provide transit to these German soldiers on 30 September. The German Troops entered Bucharest on 12 October 1940 to shouts of Heil Hitler! Hitler’s directive to the troops had stated that “it is necessary to avoid even the slightest semblance of military occupation of Romania.” In the second half of October, the new Romanian leader, Ion Antonescu, asked that the military mission be expanded. The Germans happily obliged the request. Though, technically the presence of German troops in another country bordering Russia was a violation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop “Non-Aggression” Pact of 23 August 1939, Germany’s hostile intentions towards Yugoslavia & Greece acted as the perfect ‘cover-up’.

Deployment of Axis and Yugoslav Military Formations before the Invasion

By the middle of November 1940, the German 13th Motorised Infantry Division had been assembled in Romania, and was reinforced by the 4th Panzer Regiment, engineers and signal troops, as well as six fighter and two reconnaissance Luftwaffe squadrons, and some antiaircraft artillery. A total of seventy batteries of artillery were also moved into Romania. On 23 November 1940, Romania formally joined the Axis Pact Alliance. At that time Germany had informed Romania that she would not be expected to participate in an attack on Greece, but that Germany wanted to use Romanian territory to provide a base for the German attack. On 24 November, Antonescu met Wilhelm Keitel, chief of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, to discuss defence matters. Consequent to this meeting, the 16th Panzer Division was sent to Romania in late December. The German 12th Army and First Panzer Group, along with heavy bridging equipment for the planned crossing of the Danube, followed in January 1941. By January 1941 the total number of German effectives in Romania was 1,70,639. Those elements of the 12th Army that were to invade Yugoslavia from Romania assembled near Timișoara, opposite the Northern Serbian region of Yugoslavia. Between November 1940 and February 1941 the Luftwaffe gradually moved 135 fighters and reconnaissance aircraft into Romania. By early April 1941 they moved a further 600 aircraft from France, Africa, and Sicily into Romania and Bulgaria in a period of ten days. The fighter and reconnaissance aircrafts were sent to airfields in Arad, Deva, and Turnu Severin, bordering Serbia. On 12 February 1940, Britain broke off diplomatic relations with Romania, on the grounds that it was an enemy-supporting country.

German Deployment in Bulgaria

Two events in early November 1940 convinced Hitler of the need to station troops especially the Luftwaffe, in Bulgaria. The first was false reports that the British were constructing an airfield on Lemnos island in North Aegean, from which they could bomb Ploiești. The second was the beginning of British air raids originating from Greek bases against Italian shipping, on 6 November 1940. Planning for the German invasion of Greece from Bulgaria began on 12 November. On 18 November, Tsar Boris III of Bulgaria met Hitler and promised to participate in an attack on Greece, but only at the last moment. Shortly thereafter, a secret German Wehrmacht team under Colonel Kurt Zeitzler entered Bulgaria to establish fuel depots, arrange for troops billeting, and to scout the terrain. They were soon followed by hundreds of Luftwaffe personnel to establish Air Observation Stations. Bombers and dive-bombers were moved into Bulgaria, beginning in November. By the end of March 1941, the Luftwaffe had 355 aircraft. On 17 February 1941, Bulgaria signed a Non-Aggression Pact with Turkey paving the way for its accession to the Axis Pact, which was signed by PM Bogdan Filov in Vienna on 1 March 1941. The greater part of the German 12th Army, augmented by VIII Flieger-korps, crossed the Danube on 2 March. They were welcomed by the Russophile population, who believed that Germany and the Soviet Union were allied! The German 12th Army was originally deployed solely for an attack on Greece. After receiving the final Directive No. 25, which projected the invasion of Yugoslavia on 8 April, this force was redeployed in three groups: one along the Turkish border, one along the Greek border, and one along the Yugoslav border.

Deployment in Hungary

German Troops

Although German troops had been refused the right to transit Hungary for the invasion of Poland in 1939, due to the changed circumstances, they were secretly permitted to pass through Hungary as civilians on their way to Romania in September 1940. The British had declared that “If Hungary were to permit German troops to pass through Hungarian territory against Yugoslavia, Britain would break off diplomatic relations, and indeed declare War.” The first German troops began their passage through Hungary on 8 October. According to British intelligence, three divisions had passed through Hungary to Romania by 2 November. On 20 November, Hungarian Prime Minister Pál Teleki under great pressure, signed the Tripartite Pact after meeting Hitler in Berchtesgarden. At the meeting, Hitler spoke of his intention to aid Italy against Greece, thereby preparing the Hungarians for his future demands. On 13 December 1940 – the day after the Hungaro-Yugoslav Non-Aggression Pact was signed, Hitler issued Führer Directive No. 20 and major German troop movements began. On 18 January 1941 an agreement was reached to store German supplies in Hungarian warehouses under Hungarian guard.

Hungarian Troops

On the day of the coup in Belgrade, Hitler informed the Hungarian ambassador that events in Yugoslavia might necessitate intervention, and that Hungary’s help would in such a case be desired. An amenable Hungarian response was hammered out in-council and delivered the following day (28 March 1941). On 30 March, Gen Friedrich Paulus arrived in Budapest and met with Henrik Werth, chief of the Hungarian general staff. The Hungarians agreed to commit five divisions for the attack on Yugoslavia. Two were to be held in reserve, with the main attack was aimed on Subotica (Szabadka in Hungarian), with a secondary operation east of the river Tisza. Because of Romania’s request that Hungarian troops be not allowed to operate in the disputed Banat region, Paulus modified the Hungarian plan and kept their troops west of the Tisza. This final plan “was put down in map form” and incorporated into Operational Order No. 25 issued that same day. This Plan committed one Hungarian Corps of three brigades – west of the Danube from Lake Balaton to Barcs, and twelve brigades (nine on the front and three in reserve) for the offensive in Bačka (Bácska). The “Carpathian Group” composed of Eighth Corps, the 1st Mountain Brigade and the 8th Border Guards (Chasseur) Brigade was also mobilized, while the Mobile Corps was held in reserve. A meeting of the Hungarian Supreme Defense Council was convened on 1 April to discuss Werth’s request for approval of the War Plan. It approved his mobilization plan, but refused to place Hungarian troops under German command, and restricted Hungarian operations strictly to the occupation of territory abandoned by the Yugoslavs. On 2 April, the British informed Hungary that she would be treated as an Enemy State, if Germany made use of her territory or facilities for an attack on Yugoslavia. On 3 April, German military units bound for Romania openly passed through Budapest. Pál Teleki the Hungarian PM who opposed Hungary getting embroiled in WW II, then committed suicide; Horthy, who was the Regent immediately cancelled the Mobilization Order, which prompted the pro-German Werth to resign. Horthy then had to back-track and authorize the full mobilization, and Werth withdrew his resignation.

Deployment of Italian Armed Forces

The Italians assigned their 2nd and 9th Armies, consisting of 22 divisions for the invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece, comprising around 3,00,000 troops. The Italian 2nd Army (Italian: 2 Armata) was commanded by Generale Vittorio Ambrosio, and consisted of one Fast (Italian: Celere) Corps, one Motorised Corps and three Infantry Corps (V Corps, VI Corps, and XI Corps); this Grouping was assembled in north-eastern Italy, poised for attacking from Istria and the Julian March along the borders with Slovenia and Croatia. In Albania, the elements of the Italian 9th Army (Italian: 9 Armata) that were involved in the campaign there, was commanded by Generale Alessandro Pirzio Biroli, and consisted of XIV Corps, XVII Corps, Zara Sector troops, and the XVII Corps assembled in northern Albania.

Military Operations

Air Operations

The German Military Campaign against Yugoslavia: “OPERATION 25”

Following the Belgrade Coup on 25 March 1941, the Yugoslav armed forces were put on alert, although the Army was not fully mobilised for fear of provoking Hitler. At the beginning of the April War, the VVKJ was armed with some 60 German designed Do 17Ks purchased by Yugoslavia in the autumn of 1938, together with a manufacturing licence. Their sole operator was the 3rd Bomber Regiment composed of two Bomber Groups; the 63rd Bomber Group stationed at Petrovec airfield near Skopje and the 64th Bomber Group stationed at Milesevo airfield near Priština. The VVKJ command decided to disperse its forces away from their main bases to a system of 50 auxiliary airfields; that had previously been prepared. Many of these airfields lacked facilities and had inadequate drainage, which prevented continued operation of all but the very lightest aircraft, in the adverse weather conditions encountered in April 1941. On 6 April, Luftwaffe dive-bombers and ground-attack fighters destroyed 26 of the Yugoslav Dorniers in the initial assaults on their airfields. By the end of the campaign, 45 got destroyed on the ground. The Yugoslav bomber and maritime air-force hit targets in Italy, Germany (Austria), Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania and Greece, and engaged attacking German, Italian and Hungarian troops. Meanwhile, the fighter squadrons inflicted not insignificant losses on escorted Luftwaffe bomber raids on Belgrade and Serbia, as well as upon the Regia Aeronautica raids on Dalmatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina and Montenegro. Despite having a substantially stronger force of relatively modern aircraft than the combined British and Greek air forces to the south, the VVKJ could simply not match the overwhelming Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica superiority in terms of numbers, tactical deployment and combat experience. After a combination of air combat losses, losses on the ground, and the overrunning of airfields by enemy troops; after 11 days the VVKJ ceased to exist. On 14 and 15 April, the seven remaining Do 17K flew to Nikšić airfield in Montenegro and took part in the evacuation of the Yugoslav government to Paramitia airfield in Greece. Five of these Do 17Ks soon got destroyed, when Italians carried out a raid in strength.

Ground Operations

The Germans, thrusting north-west from Skopje (in Macedonia), were held up at the Kacanik Pass and lost several tanks. Yugoslavia’s defences were badly compromised on 10 April 1941, when the Croatian-manned 4th and 7th Armies mutinied and the newly formed “Independent-Croatia” government hailed the entry of the Germans into Zagreb. The invasion and resultant fighting can be divided into two phases. The First Phase encompasses the Luftwaffe‘s devastating air assault on Belgrade and other major airfields of the Yugoslav Air Force on 6 April, and the thrust of the German 40 Panzer Corps from Bulgaria towards Skopje that also commenced the same day. This was followed by the assault of the German 14 Panzer Corps from Bulgaria towards Niš on 8 April. The Second Phase commenced on 10 April and four more thrusts struck the Yugoslav Army; the SS 51 Panzer Corps from Romania towards Belgrade, the 46 Panzer Corps from Hungary across the Drava River, the German 51 Corps from Austria towards Zagreb, and the German 49 Mountain Corps from Austria towards Celje. By the end of that day, the Yugoslav Army started disintegrating, and was either in retreat or surrendering right across the country, with the exception of the forces on the Albanian frontier. The Yugoslav high command had intended to use Niš (facing the Bulgarian frontier) as the lynch-pin in their attempts to wear down the German forces. When the Germans broke through – the Yugoslav Supreme Command committed its Strategic Reserves, but these were successfully interdicted by the Luftwaffe. Having reached Niš from its initial attacks from Bulgaria and broken the Yugoslav defences, the German 14th Panzer Corps headed north in the direction of Belgrade. The German 46th Panzer Corps had simultaneously advanced across the Slavonian plain from Austria to attack Belgrade from the west, whilst the SS 41st Panzer Corps threatened the city from the north, after launching its offensive drive from Romania and Hungary. By 11 April, Yugoslavia was criss-crossed by German armoured columns and the only resistance that remained was a large nucleus of the Yugoslav Army around the capital. After a day of heavy fighting, German columns broke through these defences and Belgrade was physically occupied by the night of 12 April. Italy and Hungary joined the ground offensive on 11 April. The Italian part in the ground offensive began when their 2nd Army attacked from north-eastern Italy towards Ljubljana and swept down the Dalmatian coast, meeting virtually no resistance. On the same day, the Hungarian 3rd Army crossed the Yugoslav border and advanced toward Novi Sad, and like the Italians they too met no serious resistance. On 12 April, Ljubljana fell to the Italians. On 14 and 15 April, King Peter and the Yugoslavian government flew out of the country, and the Yugoslav Supreme Command near Sarajevo was overrun by the Germans. The Yugoslavs surrendered on 17 April.

Details of the Italian Offensive

On 11 April, the Italian 2nd Army launched its offensive, capturing Ljubljana, Sussak and Kraljevica. On 12 April, the 133rd Armoured Division (Littorio) and the 52nd Infantry Division (Torino) of the Italian Motorised Corps took Senj; on 13 April they occupied Otočac and Gradac. The garrison troops in the Italian enclave of Zara on the Dalmatian coast, then started to advance until they met the “Torino” Division near Knin, which was taken on 14 April. Split and Sibenik were taken on 15 and 16 April respectively, and by 17 April the Italian Motorized Corps took Dubrovnik, after covering 750 kilometers in six days. After repelling the Yugoslav offensive in Albania, the 18th Infantry Division (Messina) took Cetinje and Kotor on 17 April, meeting with the units of the Motorized Corps.

Details of the Hungarian Offensive

On 12 April the Hungarian Third Army crossed the border with one cavalry, two motorized and six infantry brigades. The Third Army faced the Yugoslav First Army. By the time the Hungarians crossed the border, the Germans had been attacking Yugoslavia for over a week. As a result, the Yugoslavian forces confronting them put up little resistance, except for the units in the frontier fortifications who held up the Hungarian advance for some time and inflicted some 350 casualties. Units of the Hungarian Third Army then advanced into southern Baranja, located between the rivers Danube and Drava, and occupied the disputed Bačka region in Vojvodina, which had a relative Hungarian majority. The Hungarians occupied only those areas which were part of it, before the post-WW I ‘un-equal’ Treaty of Trianon had ceded its territory.

Yugoslav Albanian Offensive

In accordance with the Yugoslav Army’s War Plan R-41, a strategy had been formulated that in the face of a massive German attack, a fighting retreat on all fronts except in the South be performed. Here the 3rd Yugoslav Army of the 3rd Army Group in cooperation with the Greek Army, was to launch an offensive against the Italian forces in Northern Albania. This was to secure space to enable the possible withdrawal of the main Yugoslav Army to the South/Greece. The Yugoslav Army together with the Greek and British Armies, would then form a new version of the ‘Salonika Front’ of WW I. On 8 April, the hard-pressed VVKJ even sent a squadron of fourteen Breguet 19 light bombers to the city of Florina in northern Greece. The 3rd Yugoslav Army had been assembled in the Montenegro and Kosovo regions, and composed of:

- 15th Infantry Division (Zetska)

- 13th Infantry Division (Hercegovačka)

- 31st Infantry Division (Kosovska)

- 25th Infantry Division (Vardarska)

- Cavalry Odred (Komski)

The Strategic Reserve of the 3rd Army Group, the 22nd Infantry Division (Ibarska), was situated around Uroševac in the Kosovo region. In addition, offensive operations against the Italian enclave of Zara (Zadar) on the Dalmatian coast, were to be undertaken by the 12th Infantry Division (Jadranska). The first elements of the 3rd Army launched their offensive operations in North Albania on 7 April 1941. The Zetska Division steadily advanced along the Podgorica – Shkodër road. The Komski Cavalry Odred crossed the Prokletije mountains and reached the Valjbone River Valley. South of them, the Kosovska Division broke through the Italian defences in the Drin River Valley. The Vardarska Division gained some local success at Debar, but due to the fall of Skopje on 9 April 1941, it was forced to stop its operations. There was little further progress for the Yugoslavs due to the appearance of German troops in Prizren. These advances had been supported by aircraft of the VVKJ’s 66th and 81st Bomber Groups, who attacked airfields and Italian troop concentrations around Shkodër, as well as the port of Durrës. The Servizio Informazioni Militare of the Italian Armed Forces contributed to the eventual failure of the Yugoslav offensive, as its Italian code breakers deciphered the Yugoslav codes and thereafter penetrated Yugoslav radio traffic, transmitting false orders. Between 11-13 April 1941, with German troops advancing on its rear areas, the Zetska Division was forced to retreat back to the Pronisat River, pressed on by the Italian 131st Armoured Division (Centauro). The Centauro Division then advanced upon Kotor, and also occupied Cettinje and Podgorica.

The Croats Uprising

Croats in the 40th Infantry Division (Slavonska) rebelled on the evening of 7–8 April near Grubišno Polje. The rebelling Croats then entered Bjelovar, where the city’s mayor proclaimed the “Independent State of Croatia”. With the deteriorating situation in the area, the Yugoslav 4th Army’s headquarters was moved from Bjelovar to Popovača. On 10 April, there were clashes between the Croat Ustaša supporters and Yugoslav troops in Mostar, with the former taking control of the city. Several VVKJ aircraft were damaged and disabled at the nearby Jasenica airfield. On 11 April, Croat Ustaša agents took power in Čapljina. They disarmed VKJ troops moving by rail. Loyal troops from Bileća retook the town, but Germans soon arrived.

Losses

The losses sustained by the German attack forces were unexpectedly light. During the twelve days of combat, their total casualty figures came to 558 men. The Luftwaffe lost approximately 60 aircraft shot down over Yugoslavia. Italian casualties on all fronts during the invasion amounted to some 3300, whilst the Italian Air Force lost approximately 10 aircraft shot down.

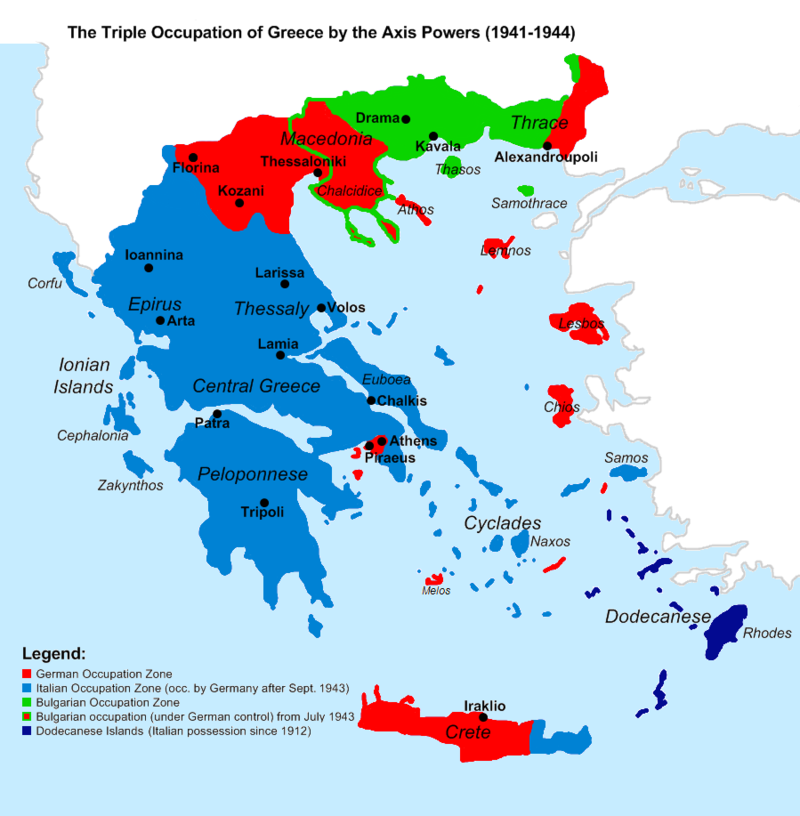

Occupation and Partition of Yugoslavia – end April 1941

Battle of Greece

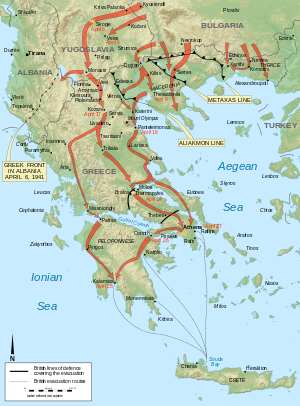

The Battle of Greece (known as Operation Marita, German: Unternehmen Marita) is the common name for the invasion of Allied Greece by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany in April 1941. These campaigns were part of the “Greater Balkan Strategy” of Germany. Following the Italian invasion on 28 October 1940, Greece was able to repulse the initial Italian attacks. When the German invasion began on 6 April 1941, the bulk of the Greek Army was on the Greek border with Albania, then a conquered protectorate of Italy, from which the Italian troops had attacked. The German troops invaded from Bulgaria, thus creating a Second Front for the Greeks. Greece received a British Empire Expeditionary Force in anticipation of the German attack. The Greek army found itself outnumbered in its efforts to defend against both Italian and German Forces. As a result, the Metaxas Defensive Line was overrun by the Germans, who then outflanked the Greek forces at the Albanian border, forcing their surrender. British, Australian and New Zealand forces were overwhelmed and forced to retreat. For several days, Allied troops played an important part in containing the German advance – on the Thermopylae position, allowing ships to be prepared to evacuate the Expeditionary Force in Greece. The German Army reached the capital, Athens, on 27 April and Greece’s southern shores on 30 April, capturing 7,000 British, Australian and New Zealand personnel, and ending the campaign with a decisive victory. The conquest of Greece was completed with the capture of Crete a month later.

At the outbreak of World War II, Ioannis Metaxas – the benign dictator of monarchist Greece and former general – had sought to maintain a position of neutrality. Italian leader Benito Mussolini hoped to match German military success by taking Greece, which he regarded as an easy opponent. On 15 October 1940, Mussolini and his closest advisers finalised their decision. In the early hours of 28 October, Italian troops invaded Greece through Albania. The principal Italian thrust was directed toward Epirus. Hostilities with the Greek army began at the Battle of Elaia-Kalamas, where they failed to break the defensive line. Within three weeks, the Greek army launched a counter-offensive, during which it marched into Albanian territory, capturing significant towns such as Korça and Sarandë. Neither a change in Italian command nor the arrival of substantial reinforcements improved the position of the Italian Army. On 13 February, the Greeks launched an offensive aiming to take Tepelenë and the port of Vlorë, which failed. After weeks of inconclusive winter warfare, the Italians launched another offensive on 9 March 1941. After one week and 12,000 casualties, Mussolini called off the operation. Modern analysts believe that the Italian campaign failed because Mussolini and his generals initially allocated insufficient resources to the campaign (an expeditionary force of 55,000 men), failed to reckon with the autumn weather, attacked without the advantage of surprise, and without forming a prior military alliance with Bulgaria. Elementary precautions such as issuing winter clothing had not been taken. Mussolini had not given heed to the warnings of the Italian Commissioner of War Production, that Italy would not be able to sustain a full year of warfare.

At the outbreak of World War II, Ioannis Metaxas – the benign dictator of monarchist Greece and former general – had sought to maintain a position of neutrality. Italian leader Benito Mussolini hoped to match German military success by taking Greece, which he regarded as an easy opponent. On 15 October 1940, Mussolini and his closest advisers finalised their decision. In the early hours of 28 October, Italian troops invaded Greece through Albania. The principal Italian thrust was directed toward Epirus. Hostilities with the Greek army began at the Battle of Elaia-Kalamas, where they failed to break the defensive line. Within three weeks, the Greek army launched a counter-offensive, during which it marched into Albanian territory, capturing significant towns such as Korça and Sarandë. Neither a change in Italian command nor the arrival of substantial reinforcements improved the position of the Italian Army. On 13 February, the Greeks launched an offensive aiming to take Tepelenë and the port of Vlorë, which failed. After weeks of inconclusive winter warfare, the Italians launched another offensive on 9 March 1941. After one week and 12,000 casualties, Mussolini called off the operation. Modern analysts believe that the Italian campaign failed because Mussolini and his generals initially allocated insufficient resources to the campaign (an expeditionary force of 55,000 men), failed to reckon with the autumn weather, attacked without the advantage of surprise, and without forming a prior military alliance with Bulgaria. Elementary precautions such as issuing winter clothing had not been taken. Mussolini had not given heed to the warnings of the Italian Commissioner of War Production, that Italy would not be able to sustain a full year of warfare.

On 12 November 1940, the German Wehrmacht issued Directive No. 18, in which they scheduled simultaneous operations against Gibraltar and Greece for the following January. In December 1940, Spain’s ‘Caudillo’ Franco rejected the Gibraltar Attack Plan. The Wehrmacht then issued Directive No. 20 on 13 December 1940, outlining the Greek campaign under the codename ‘Operation Marita’. Attacking Greece would require going through Yugoslavia/ Bulgaria. The Regent of Yugoslavia Prince Paul was married to a Greek princess, and he steadfastly refused the Germans transit rights to invade Greece. Bulgaria had territorial disputes with Greece and was far more amenable, in exchange for the promise to have the parts of Greece that it coveted. In January 1941, Bulgaria granted transit rights to the Wehrmacht. The lack of bridges on the Danube capable of carrying heavy supplies on the Romanian-Bulgarian frontier forced the Wehrmacht engineers to build the necessary bridges, causing delays. In February 1941 that the Wehrmacht’s Twelfth Army commanded by Wilhelm List joined by the Luftwaffe’s Fliegerkorps VIII crossed the Danube river into Bulgaria. By 9 March 1941, the 5th & 11th Panzer Divisions were concentrated in Bulgaria. Under heavy German threats, Prince Paul agreed to Yugoslavia joining the Axis Camp on 25 March 1941, but with the proviso that Yugoslavia would not grant transit rights to the Wehrmacht. As the Metaxas Line protected the Greek-Bulgarian border, the Wehrmacht generals preferred the idea of attacking Greece via Yugoslavia. After the unexpected 27 March Yugoslav coup d’état, new orders for the campaigns in Yugoslavia & Greece were drafted. The coup d’état in Belgrade greatly assisted German planning. On 6 April 1941, both Greece and Yugoslavia were to be attacked.

British Expeditionary Force

“We did not then know that he [Hitler] was already deeply set upon the gigantic enterprise of invasion of Russia. If we had, we would have felt more confidence in the success of our Policy. We could then have seen that he risked falling between two stools that might easily impair this supreme undertaking, for the sake of a Balkan Preliminary. Some may think we did not build up our forces in Greece rightly; at least we build them up better than we knew. It was our aim to animate and combine Yugoslavia, Greece and Turkey against the Axis might.” – Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill instructed Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden and CIGS Gen John Dill to thwart the German build-up. At a meeting in Athens on 22 February 1941, it was agreed to send a British Expeditionary Force from Egypt. On 2 March 1941, “Operation Lustre” – the transportation of troops and equipment to Greece began, and 26 troopships arrived at the port of Piraeus. On 3 April, during a meeting of British, Yugoslav and Greek military representatives, the Yugoslavs promised to block the Struma Valley in Vardar Macedonia, in case of a German attack. During this meeting, Papagos stressed a joint Greco-Yugoslavian offensive against the Italians, if war starts. 62,000 Empire troops had arrived in Greece, comprising the Australian 6th Division, the New Zealand 2nd Division and the British 1st Armoured Brigade. The three formations became known as ‘W’ Force, after their commander, Lt Gen Henry Maitland Wilson.

Topography

To enter Northern Greece from Bulgaria, the German Army had to cross the Rhodope Mountains, which offered few river valleys or mountain passes capable of accommodating the movement of large military units. Two invasion routes were selected west of Kyustendil; another was along the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border, via the Struma River valley. The Struma and Nestos rivers cut across the mountain range along the Greek-Bulgarian frontier, and both their valleys were protected by strong fortifications, as part of the larger Metaxas Line. Greece’s mountainous terrain favoured a defensive strategy. The Albanian frontier required smaller number of troops positioned in the high Pindus mountains, but the northeastern parts of Greece required more troops to defend. The British believed that they would combine with Greek forces to occupy the Haliacmon Line – a short front facing north-eastwards along the Vermion Mountains and the lower Haliacmon River. Papagos instead proposed to hold the Metaxas Line – by then a symbol of national security to the Greek populace – and secondly, not withdraw some of the required divisions from Albania, despite the awareness that the Metaxas Line was likely to collapse in the event of a German thrust from the Struma and Axios river valleys. Gen Wilson took up positions some 40 miles (64 kilometres) west of the Axios River, across the Haliacmon Line. The objectives in establishing this position were to maintain proximity with the Hellenic army in Albania, and to deny the Germans access to Central Greece. This line’s left flank however was susceptible to being turned by mobile forces operating through the Monastir Gap. The rapid collapse of the Yugoslav Army and a German thrust to the rear of the Mt. Vermion position was not anticipated. The German strategy was based on using “blitzkrieg” methods to make rapid drives into Greek territory. Once Thessaloniki was captured, Athens and the port of Piraeus became principal objectives. Piraeus was destroyed by mass German aerial bombing on the night of the 6/7 April.

To enter Northern Greece from Bulgaria, the German Army had to cross the Rhodope Mountains, which offered few river valleys or mountain passes capable of accommodating the movement of large military units. Two invasion routes were selected west of Kyustendil; another was along the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border, via the Struma River valley. The Struma and Nestos rivers cut across the mountain range along the Greek-Bulgarian frontier, and both their valleys were protected by strong fortifications, as part of the larger Metaxas Line. Greece’s mountainous terrain favoured a defensive strategy. The Albanian frontier required smaller number of troops positioned in the high Pindus mountains, but the northeastern parts of Greece required more troops to defend. The British believed that they would combine with Greek forces to occupy the Haliacmon Line – a short front facing north-eastwards along the Vermion Mountains and the lower Haliacmon River. Papagos instead proposed to hold the Metaxas Line – by then a symbol of national security to the Greek populace – and secondly, not withdraw some of the required divisions from Albania, despite the awareness that the Metaxas Line was likely to collapse in the event of a German thrust from the Struma and Axios river valleys. Gen Wilson took up positions some 40 miles (64 kilometres) west of the Axios River, across the Haliacmon Line. The objectives in establishing this position were to maintain proximity with the Hellenic army in Albania, and to deny the Germans access to Central Greece. This line’s left flank however was susceptible to being turned by mobile forces operating through the Monastir Gap. The rapid collapse of the Yugoslav Army and a German thrust to the rear of the Mt. Vermion position was not anticipated. The German strategy was based on using “blitzkrieg” methods to make rapid drives into Greek territory. Once Thessaloniki was captured, Athens and the port of Piraeus became principal objectives. Piraeus was destroyed by mass German aerial bombing on the night of the 6/7 April.

German Forces

The German forces were grouped under Wilhelm List‘s 12th Army, which comprised:

- 40 Panzer Corps (Georg Stumme), deployed against southern Yugoslavia (Vardar Macedonia)

-

-

- 9th Panzer Division

- 73rd Infantry Division

- LAH (Waffen-SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler) Motorized Regiment

-

- 18 Mountain Corps(Franz Böhme), deployed against the Greek forces along the Metaxas Line

- 50 Army Corps(Georg Lindemann), as Reserve, in Romania

- 16th Panzer Division, as Reserve, on the Bulgarian-Turkish border

Greek Forces

15 divisions of Greek forces was committed against the Italian Army, and within Albania. The remaining Greek forces were divided in the following two major groupings:

The Eastern Macedonia Army Section covered the pre-war fortifications of the Metaxas Line, between Mount Beles and the Nestos River. It mainly consisted of :

-

-

- 7th Infantry Division

- 14th Infantry Division

- 18th Infantry Division

- 21 Fortresses of the Metaxas Line

-

The Central Macedonia Army Section consisting of the 12th & 20th Infantry Divisions was assigned to ‘W’ Force on 28 March, to hold the Vermion Mountains -Haliacmon Line. General Wilson established his headquarters near Larissa. The New Zealand division took position north of Mount Olympus, while the Australian division blocked the Haliacmon Valley up to the Vermion Range. Greek troops defending Western Thrace less Border forces had been evacuated by March end. The 5th Yugoslav Army was deployed between Kriva Palanka and the Greek border.

German Plan of Attack and Assembly

By the evening of 5 April, the forces intended to enter southern Yugoslavia and Greece had been assembled. At dawn on 6 April 1941, the German armies invaded Greece. The 40 Panzer Corps pushed across the Bulgarian frontier into Yugoslavia at two separate points. By the evening of 8 April, the 73rd Infantry Division captured Prilep, severing the important rail line between Belgrade and Thessaloniki, and isolating Yugoslavia from its Allies. Once Southern Yugoslavia was overrun by German armour, the Metaxas Line could be outflanked by highly mobile forces thrusting southward from Yugoslavia. On the evening of 9 April, Stumme deployed his forces north of Monastir, in preparation for attack toward Florina. This thrust was designed to cut off the Greeks in Albania and ‘W Force’ elements in Florina, Edessa and Katerini. While some security detachments covered the rear against any surprise attack from central Yugoslavia, the 9th Panzer Division drove westward to link up with the Italians at the Albanian border. The 2nd Panzer Division (18 Mountain Corps) entered Yugoslavia from the east on 6 April and advanced westward through the Struma Valley. It encountered little resistance, but was delayed by road clearance demolitions, mines and mud. The division was able to reach the town of Strumica. On 7 April, a Yugoslav counter-attack against the division’s northern flank was repelled, and the following day (8 April), the division forced its way across the mountains and overran the thinly manned defensive line of the Greek 19th Mechanised Division, south of Doiran Lake. Despite many delays along the mountain roads, an armoured advance guard dispatched toward Thessaloniki succeeded in entering the city by 9 April. This was followed by the surrender of the Greek Eastern Macedonia Army Section, on 10 April. It took three days for the Germans to breach the Metaxas Line and reach Thessaloniki .

Fall of the Metaxas Line

The Metaxas Line was defended by the Greek Army’s Eastern Macedonia Army Section, comprising the 7th, 14th and 18th Infantry Divisions. The line ran for about 170 km (110 miles) along the river Nestos to the east, and thereafter followed the Bulgarian border as far as Mount Beles. The fortifications were manned by about 70,000 troops. The German attack started on 6 April with two divisions and one infantry regiment of the 18 Mountain Corps. Due to strong resistance, the first day of the attack yielded little progress. In the following days, the Germans pummelled the forts with artillery and dive bombers. Finally a 7,000 ft (2,100 m) high snow-covered mountainous passage considered inaccessible by the Greeks, was crossed by the German 6th Mountain Division, which reached the rail line to Thessaloniki on the evening of 7 April. The 5th Mountain Division, together with the reinforced 125th Infantry Regiment, crossed the Struma River under great hardship on 7 April. The 72nd Infantry Division also advanced from Nevrokop across the mountains, and on the evening of 9 April it reached the area north-east of Serres. Most fortresses held, until the Germans occupied Thessaloniki on 9 April.

Capitulation of the Greek Army in Macedonia

The 164th Infantry Division of German 30 Infantry Corps captured Xanthi on 8 April. The 50th Infantry Division advanced far beyond Komotini towards the Nestos River. On 9 April, the Greek forces defending the Metaxas Line capitulated unconditionally following the collapse of Greek resistance east of the Axios River. Field Marshal List judged that his 12th Army was in a favourable position to access central Greece, by breaking the Greek build-up behind the Axios River. He obtained the transfer of 5th Panzer Division from 1st Panzer Group to the 40 Panzer Corps. For the continuation of the campaign, he formed an Eastern Group under the command of 18 Mountain Corps and a Western Group led by 40 Panzer Corps.

Breakthrough to Kozani

By the morning of 10 April, the 40 Panzer Corps had finished its preparations for the continuation of the offensive and advanced in the direction of Kozani. The 5th Panzer Division, advancing from Skopje encountered a Greek division tasked with defending Monastir Gap, and rapidly defeated the defenders. First contact with Allied troops was made north of Vevi at 11:00 on 10 April. LAH seized Vevi on 11 April. During the next day, LAH took advantage of bad weather and launched a frontal attack against the Klidi Pass. The Germans broke through the defences. By the morning of 14 April, the spearheads of the 9th Panzer Division reached Kozani.

Battles of Olympus and Servia Passes

Wilson faced the prospect of being pinned by Germans operating from Thessaloniki, while being outflanked on the West by the German 40 Panzer Corps descending through the Monastir Gap. On 13 April, he withdrew all British forces to the Haliacmon River. This defence had three main components: the Platamon tunnel area between Olympus and the sea, the Olympus Pass itself and the Servia Pass to the south-east. By channelling the attack through these three defiles, the new line offered far greater defensive strength. These defences were manned by the 4th New Zealand Brigade, 5th New Zealand Brigade and the 16th Australian Brigade. On 14 April, the 9th Panzer Division established a bridgehead across the Haliacmon River, but an attempt to advance beyond was stopped for the next three days. The failure of the Greek Western Macedonia Army to defend the Albanian town of Korça that fell to the Italian 9th Army on 15 April, forced the British to abandon the Haliacmon River Defence Line. On 16 April, Wilson met Papagos at Lamia and informed him of his decision to withdraw to Thermopylae. Lt Gen Thomas Blamey divided responsibility between Mackay and Freyberg during the leapfrogging move to Thermopylae. Brig Harold Charrington’s 1st Armoured Brigade was placed under command of the Australian 6th Division. The British, Australian and New Zealand forces remained under attack throughout the withdrawal. On the morning of 18 April, the Battle of Tempe Gorge and the struggle for the Pineios Gorge ended when German armoured infantry crossed the Pineios river on floats, and German 6th Mountain Division expanded the crossing. On 19 April, German 18 Mountain Corps troops entered Larissa and took possession of the prominent airfield, where the hurriedly fleeing British had left their supply dump intact! The port of Volos, at which the British had evacuated numerous units fell on 21 April; there again, the Germans captured large quantities of FOL.

Withdrawal and Surrender of the Greek Epirus Army

As the invading Germans advanced deep into Greek territory, the Epirus Army Section of the Greek army operating in Albania was reluctant to retreat. General Wilson described this unwillingness to retreat as the fetishist doctrine, “that not a yard of ground should be yielded to the Enemy.” Stumme‘s 40 Panzer Corps captured the Florina-Vevi Pass on 11 April, but unseasonal snowy weather halted his advance. The next day was spent fighting Charrington’s 1st Armoured Brigade at Proastion. On 13 April the Greek elements in Albania began to withdraw toward the Pindus Mountains, with the Italians in hesitant pursuit. The Allies’ retreat to Thermopylae uncovered a route across the Pindus mountains, by which the Germans might flank the Hellenic army in a rearguard action. The LAH was assigned this mission of cutting off the Greek Epirus Army’s line of retreat, by driving westward to the Metsovon Pass, and from there to Ioannina. General Papagos rushed Greek units to the Metsovon Pass. On 14 April a pitched battle erupted between Greek units and the LAH Brigade – which had by then reached Grevena. The Greek 13th and Cavalry Divisions were overwhelmed by the LAH on 15 April. On 13 April the Greek 20th Division covering the Greek withdrawal, had delayed Stumme’s advance at the Kleisora Pass. On 15 April, Regia Aeronautica fighters attacked the airbase at Paramythia, destroying 17 of the VVKJ aircraft that had recently arrived. On 18 April, Wilson informed Papagos that the British and Commonwealth forces at Thermopylae would carry on fighting till the first week of May, provided that Greek forces from Albania could redeploy and cover the left flank. On 21 April, the German LAH advanced further and captured Ioannina, and cut the supply route of the Greek Epirus Army. On 20 April, the commander of Greek forces in Albania – Lt Gen Georgios Tsolakoglou – accepted the hopelessness of the situation and offered to surrender his Army which then consisted of fourteen divisions, to the Germans. The Greeks so hated the Italians that, Tsolakoglou was determined to deny them the satisfaction of a Victory! He opened an unauthorised parley with Sepp Dietrich the commander of the LAH. On strict orders from Hitler, negotiations were kept secret from the Italians, and the surrender was accepted on 21 April. Never in history, had such a large force surrendered to so few! Outraged by this decision, Mussolini ordered fierce attacks against the Greek forces, which were repulsed. It later took a personal representation from Mussolini to permit Italian participation in the armistice on 23 April, followed by the triumphant march of the Axis Troops into Athens!

Battle of the Thermopylae Position

As early as 16 April, the German command realised that the British were evacuating troops on ships at Volos and Piraeus ports. The 2nd and 5th Panzer Divisions, the LAH and both mountain divisions launched a pursuit of the Allied forces. To allow the evacuation of the main body of British forces, Wilson ordered the rearguard to make a last stand at the historic Thermopylae Pass, the gateway to Athens. On 23 April, it was decided that the 19th Australian Brigade will hold the Pass and 6th New Zealand Brigade will hold the coastal area around Brallos. The Germans attacked on 24 April and met fierce resistance. The Allies then retreated in the direction of the evacuation beaches. The Panzer units leading the pursuit along the road going down the Pass made slow progress, because of the steep gradient and difficult hairpin bends.

German Drive on Athens

After abandoning the Thermopylae area, the British rearguard withdrew to an improvised Delay Position south of Thebes, where they erected a last obstacle in front of Athens. The motorcycle battalion of the 2nd Panzer Division was given the mission of outflanking the British rearguard. The motorcycle troops encountered only slight resistance, and on the morning of 27 April 1941, the first Germans entered Athens, followed by armoured cars, tanks and infantry. They again captured intact large stocks of war material. General Archibald Wavell had authorised his Staff on 13 April to plan the evacuation of the Expeditionary Force. The following day, Papagos suggested to Wilson that ‘W Force’ be withdrawn. On 17 April, Rear Adm. Baillie-Grohman was sent to Greece to carry out the evacuations. That evening the Greek PM Koryzis like the Hungarian PM, committed suicide, taking moral responsibility for the defeat of his nation. On 21 April, the 5,200 men of the 5th New Zealand Brigade withdrew and were evacuated on the night of 24 April, from Porto Rafti in East Attica, while the 4th New Zealand Brigade remained to block the narrow road to Athens. On 25 April (Anzac Day), the RAF squadrons left the Greek mainland, with some elements redeployed to Heraklion in Crete. Some 10,200 Australian troops were evacuated from Nafplio and Megara Ports. 2,000 more men had to wait until 27 April, because their evacuation ship Ulster Prince ran aground in the shallow waters close to Nafplio, on the East coast of Peleponnese. This was noticed by the Germans. The Dutch ship Slamat was part of the last convoy, escorted by the destroyers HMS Diamond & HMS Wryneck evacuating about 3,000 troops from Nafplio. These three ships were sunk by the Luftwaffe. On 25 April the Germans staged an airborne operation to seize the bridge over the Corinth Canal, with the double aim of cutting off the British line of retreat, and securing their own way across the isthmus. A stray British shell however destroyed the bridge. The LAH, assembled at Ioannina, thrust along the western foothills of the Pindus Mountains via Arta to Missolonghi, and then crossed over to the Peloponnese at Patras. The construction of an assault bridge across the Corinth Canal permitted 5th Panzer Division units to pursue the Allied forces across the Peloponnese. Driving via Argos to Kalamata, from where most Allied units had already begun to be evacuated, they reached the south coast on 29 April, where they were joined by the LAH arriving from Pyrgos. This twin attack isolated the Australian 16th & 17th Brigades, and around 7,000 troops got captured. By 30 April the evacuation of about 50,000 soldiers was done but the Luftwaffe also inflicted serious damage, sinking 26 troop-laden ships.

Battle of Crete

Germans employed parachute forces on 20 May 1941 for an airborne invasion, and targeted the airfields at Maleme, Rethymno and Heraklion. After seven days of tough fighting, Allied forces were evacuated from Sfakia. Crete also came under German occupation on 1st June.

Assessment of the Balkan Operations

The British did not have the military resources to carry out big simultaneous operations both in North Africa and Greece. In enumerating the reasons for the complete Axis victory in the Balkans, the following factors are of greatest significance:

-

- German superiority in ground and air forces – organisation, operational art and equipment.

- Bulk of the Greek Army continued to be tasked to fight the Italians on the Albanian Front, ignoring the emerging greater German threat.

- Overall inadequacy of the British Empire Expeditionary Force.

- Poor condition of the Hellenic Army, and its shortages of modern equipment.

- No advance preparation made for smooth leap-frogging between successive Defensive Lines.

- Absence of practical and workable ‘Defensive Battle Plans’, by the Yugoslav, Greek & British militaries. Poor coordination and lack of contingency planning for placing strong mobile Reserves with dense AD capabilities close at hand, for launching of quick counter attacks.

- The ill-timed Yugoslav coup de tat. Its military’s officers cadre was not representative of all its Provinces, which grave failing should have been corrected in the years preceding WW II.

Criticism of British Actions

Many considered the intervention in Greece to be “a definite strategic blunder”, as it denied Wavell the necessary reserves to complete the timely conquest of Italian Libya, or to withstand Erwin Rommel‘s Afrika Korps’ March 1941 offensive. It thus prolonged the North African Campaign. The British strategy was also aimed to desist Turkey from joining the Axis block. The campaign caused a furore in Australia, and PM Robert Menzies had to step down. Australia and New Zealand withdrew their military Contingents from North Africa.

Impact on Operation Barbarossa

Seen in retrospect, the Battle of Greece delayed Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union. According to film-maker Leni Riefenstahl, Hitler had said that, “If the Italians hadn’t attacked Greece and needed our help, the War would have taken a different course. We could have avoided the Russian winter by weeks, and conquered Leningrad and Moscow. There would never have been a Stalingrad!” Experts conclude that although no single segment of the Balkan campaign forced the Germans to delay ‘Op Barbarossa’, obviously the entire campaign prompt them to wait. Basil Liddell Hart has pointed out that delaying of the German invasion of the Soviet Union was not then among Britain’s strategic goals, and Britain deliberately chose to commit forces, so as not to give Nazi Germany a free run in the Balkans. Most military historians agree that the main causes for deferring Barbarossa’s start from 15 May to 22 June 1941 were incomplete logistical arrangements, and coincidentally an unusually wet winter that kept rivers in Eastern Poland and Western USSR at full flood until late spring. The German invasion of the Balkans certainly “helped conceal Barbarossa” from the Soviet leadership, and contributed to the German success in achieving strategic surprise. The Panzer divisions and other Units which had participated in the Balkan Campaign, required 6 weeks to undergo refit and then redeployment to their fresh launch-pads.

Seen in retrospect, the Battle of Greece delayed Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union. According to film-maker Leni Riefenstahl, Hitler had said that, “If the Italians hadn’t attacked Greece and needed our help, the War would have taken a different course. We could have avoided the Russian winter by weeks, and conquered Leningrad and Moscow. There would never have been a Stalingrad!” Experts conclude that although no single segment of the Balkan campaign forced the Germans to delay ‘Op Barbarossa’, obviously the entire campaign prompt them to wait. Basil Liddell Hart has pointed out that delaying of the German invasion of the Soviet Union was not then among Britain’s strategic goals, and Britain deliberately chose to commit forces, so as not to give Nazi Germany a free run in the Balkans. Most military historians agree that the main causes for deferring Barbarossa’s start from 15 May to 22 June 1941 were incomplete logistical arrangements, and coincidentally an unusually wet winter that kept rivers in Eastern Poland and Western USSR at full flood until late spring. The German invasion of the Balkans certainly “helped conceal Barbarossa” from the Soviet leadership, and contributed to the German success in achieving strategic surprise. The Panzer divisions and other Units which had participated in the Balkan Campaign, required 6 weeks to undergo refit and then redeployment to their fresh launch-pads.

Conclusion

The German Balkan Campaign during WW II is one of the least studied military campaigns. Its close study would be useful for Indian military planners, as the terrain is similar to our border regions. Keeping close track of military and political developments, and thereafter swiftly modifying our equipment profile and war doctrine has to be constantly done by the country’s military leadership, otherwise the fate met by the brave Yugoslavs and Greeks would befall our nation too when confronted by a superior organised and ruthlessly efficient aggressor. It is no secret that the Israeli military are the best students of the German Wehrmacht, and their employment of forces and military techniques bear close resemblance. The Organisational structures and Operational Art techniques employed by the German Armed Forces can be further improved upon, as per the evolution in military thinking, technology and equipment. The fundamental principle to negate aggression by a powerful Enemy, is to first trap him into a ‘stalemate’. This requires having the main defensive line in depth; and by having mobile reserves well forward, both to block as well as to cut off the supply lines, of the Enemy penetrations.

References: Wikipedia and Other Open Sources.