There are many, particularly in the so-called development fraternity, who view defence as a wasteful expenditure that uses up precious resources at the cost of development. This guns vs butter debate is age old. Much of this stems from a legacy of over 50 years of treating defence as non-plan expenditure and therefore, viewed as something that does not contribute to national development. Hence, defence planning and defence expenditures have lacked a long-term strategic orientation and the lack of conviction that it contributes to economic and technological strength as well as national development. This also stems from a carefully cultivated national narrative that does not give any space or role to the Indian military in the history of India’s march to independence and development.

Early last month, the Indian Army announced that it was cutting down its projected requirement of 800,000 assault rifles to 250,000 rifles in view of the severe financial crunch. The Army said it will reprioritise its modernisation expenditures in view of the very limited funds allocated. In February this year, in his statement to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Defence, the former Vice Chief of the Army Staff (VCOAS), Lt Gen Sarath Chand, stated that the budgetary allocation for the financial year 2018-2019 had ‘dashed the hopes’ of the Indian Army for any meaningful modernisation. Poor budgetary allocation has been the major problem for the modernisation of the Indian Army over the last decade.

In October 2017, the Chief of the Army Staff indicated the scrapping of a major modernisation programme, the Battlefield Management System (BMS), in favour of more immediate and pressing routine requirements. That was an indication of how precarious the Army’s position is with respect to its equipment and weapons. The statement by the VCOAS to the Standing Committee was a clear indication of this situation that 68 per cent of its equipment is vintage, only 24 per cent is of current technology and eight per cent is fit enough to be displayed as museum pieces. So much for the Indian Army’s combat capability; the Indian Air Force and the Indian Navy would fare no better. There is no doubt that when it comes to a crunch, the Indian military will fight with whatever it has. It is also true that in times of crisis, the government will rush to friendly countries such as Israel, Sweden, France and Russia to procure the required ammunition and equipment on a war footing. This happened during the war in Kargil in 1999, and even earlier in 1987. But is this the way to ensure that the military is well equipped, particularly for a nation that aspires to be a great power?

Defence Budget – Victim of Guns vs Butter Lobby

There are many, particularly in the so-called development fraternity, who view defence as a wasteful expenditure that uses up precious resources at the cost of development. This guns vs butter debate is age old. Much of this stems from a legacy of over 50 years of treating Defence as non-plan expenditure and therefore, viewed as something that does not contribute to national development. Hence, defence planning and defence expenditures have lacked a long-term strategic orientation and the lack of conviction that it contributes to economic and technological strength as well as national development. This also stems from a carefully cultivated national narrative that does not give any space or role to the Indian military in the history of India’s march to independence and development. As new evidence emerges now, it becomes clear that this is a deeply flawed interpretation of the history of modern India. However, most will see the reason that defence is necessary to ensure a secure and a stable nation and as the first and foremost requirement for all other instruments of governance and development to function. Defence budget therefore, should have continuity and long-term strategy linked to national development and growth.

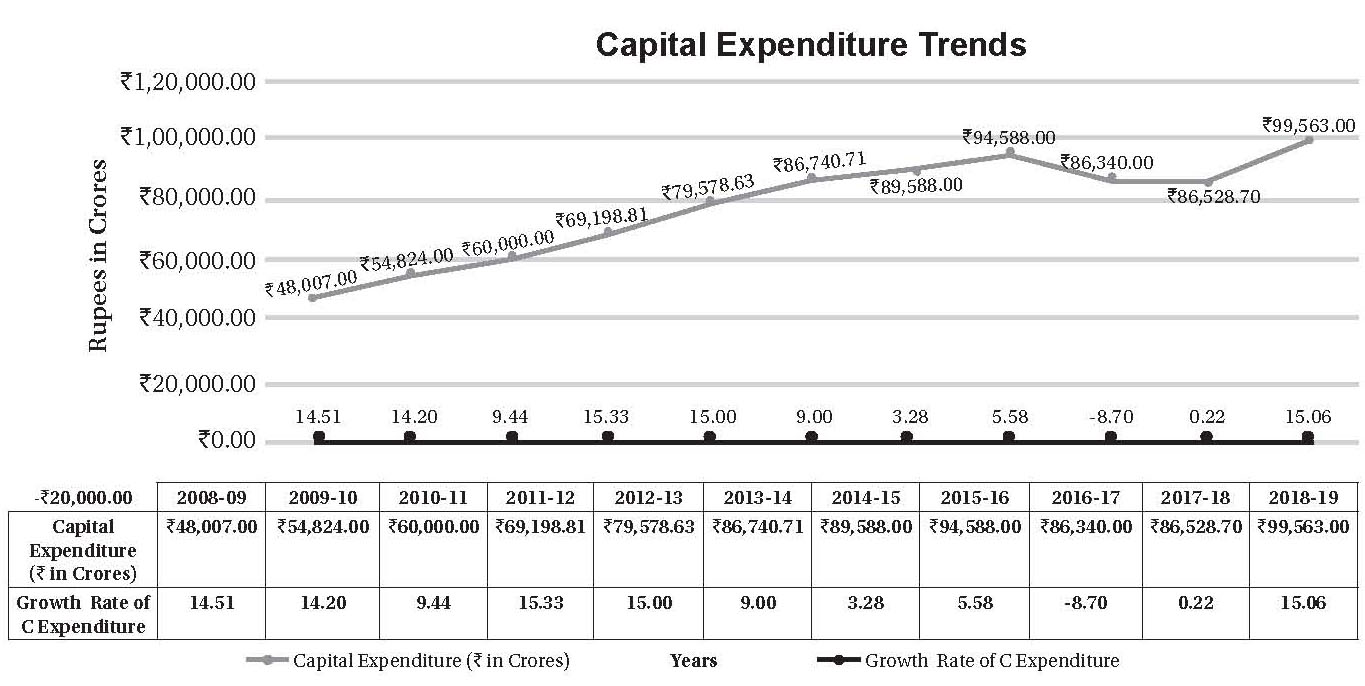

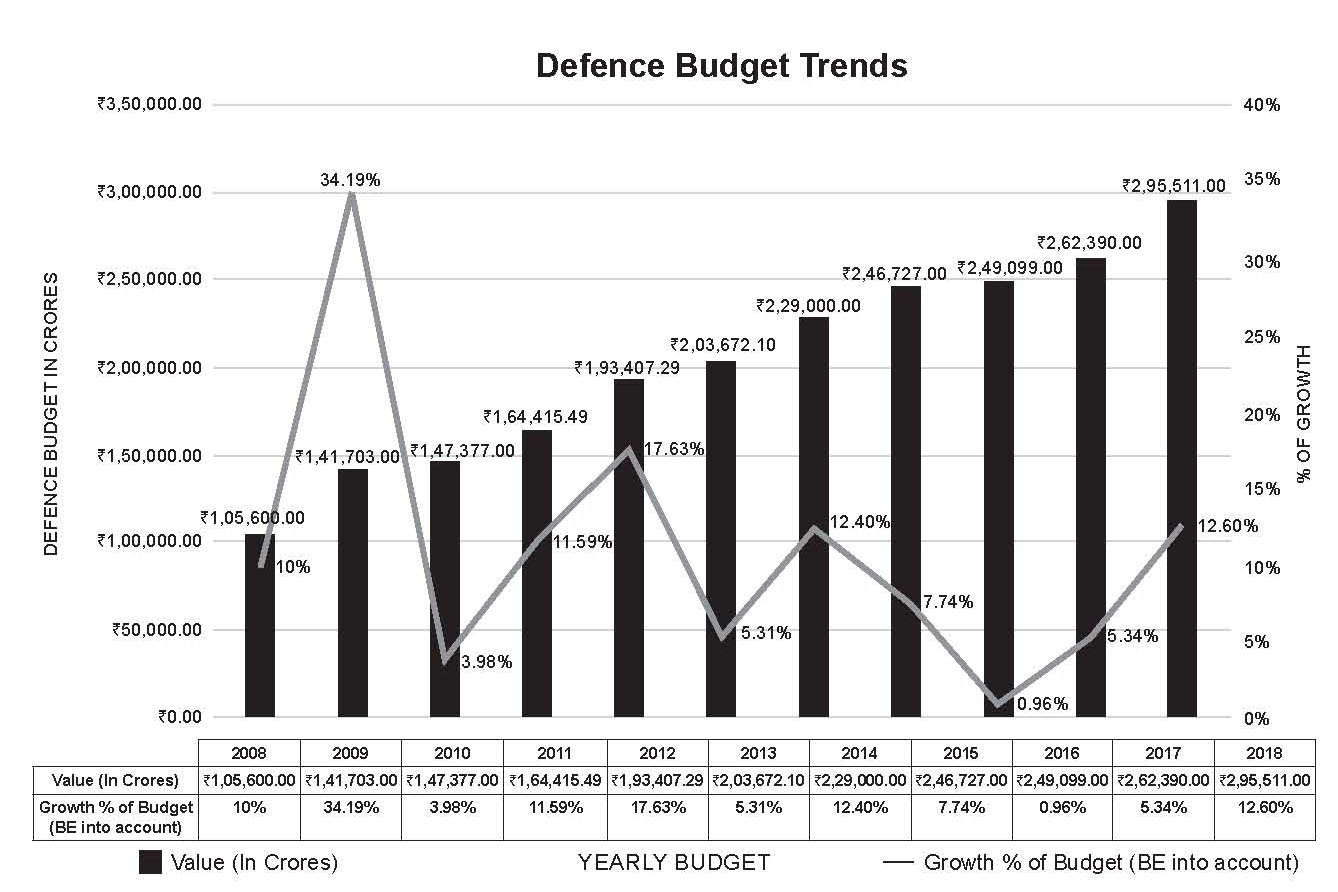

In the budget presentation for financial year 2018-2019, the Finance Minister mentioned an allocation of `4,04,365 crore for defence which is inclusive of defence pensions of `1,08,853 crore. This approach itself is misleading. The pension allocation must become part of overall central pension allocation, which is five per cent of overall expenditure and include the pension for all government employees. Although defence pension conditions may differ from others, which is policy and management related, it should be separated from the defence budget. In most countries such as in the US, defence pensions are managed by the department of veteran affairs and do not form part of the defence budget. Secondly, salaries and maintenance, which is the revenue outlay, are part of all government departments and ministries. These are mandatory expenditures of the government and hence to raise a hue and cry on the huge liability on salaries, obfuscates poor planning on the part of the government. Effectively, this year’s budget estimate is `2,95,511 crore, a marginal increase by 7.81 per cent over last year’s expenditure of `2,74,114 crore. Capital expenditure allocation of `99,563 crore, is barely sufficient for any meaningful modernisation. Hence, the pique from the Army leadership.

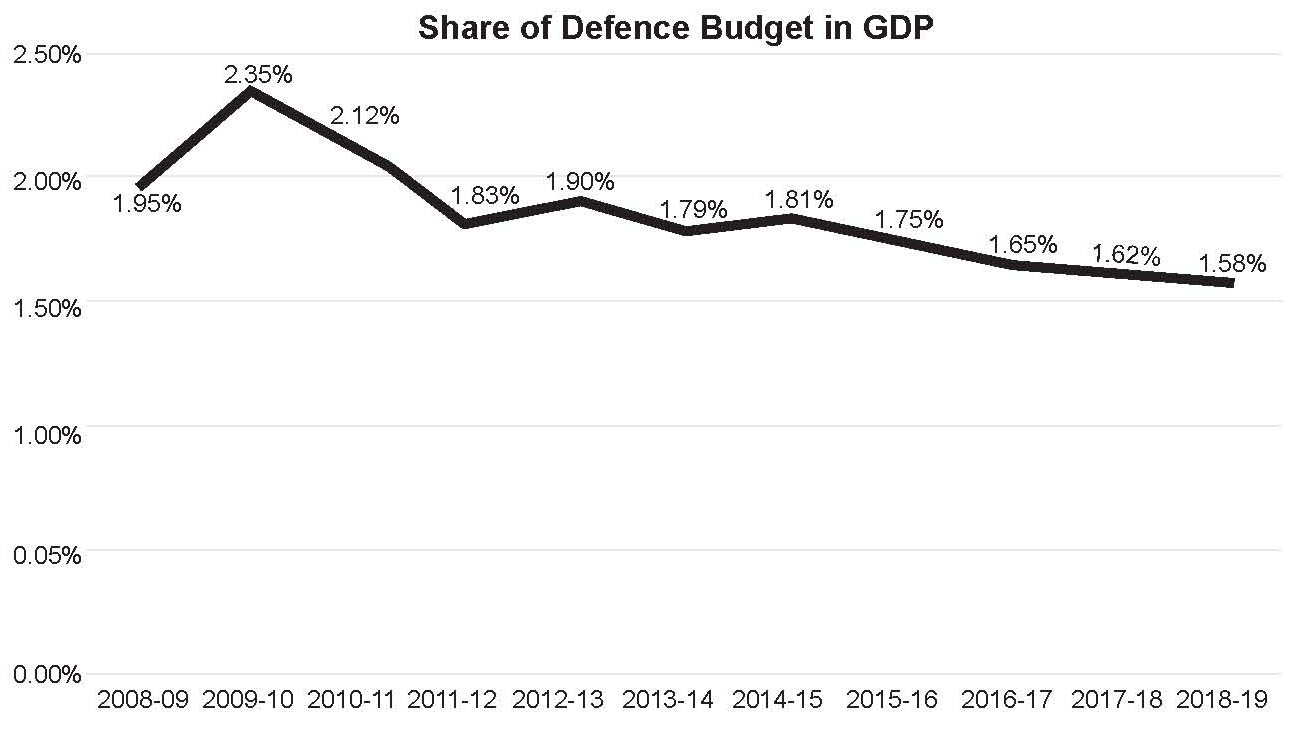

Indian defence budgeting needs a radical transformation. The oft repeated concern that we are heavily import dependent for defence equipment, will remain mere statements if the country does not address defence with a long-term perspective that needs continuity in its strategy and investments. ‘Make in India’ and other such announcements will remain mere slogans. This year’s budget is 1.58 per cent of GDP, the lowest since the 1962 India-China War. That war was the result of poor understanding of defence and security issues by Prime Minister Nehru and his fixed notion that defence was a wasteful expenditure. On November 19, 1962, Prime Minister Nehru wrote to the American President John F Kennedy, literally begging him to save India as the North East was falling into Chinese hands. Any self-respecting Indian would hang his head in shame when he reads that letter. More than 50 years later, while we are certainly in a far better position, our approach to defence planning and defence expenditure is still hampered by the lack of proper strategic analysis and long-term planning.

Capital Outlay – Lack of Continuity and Long-term Strategy

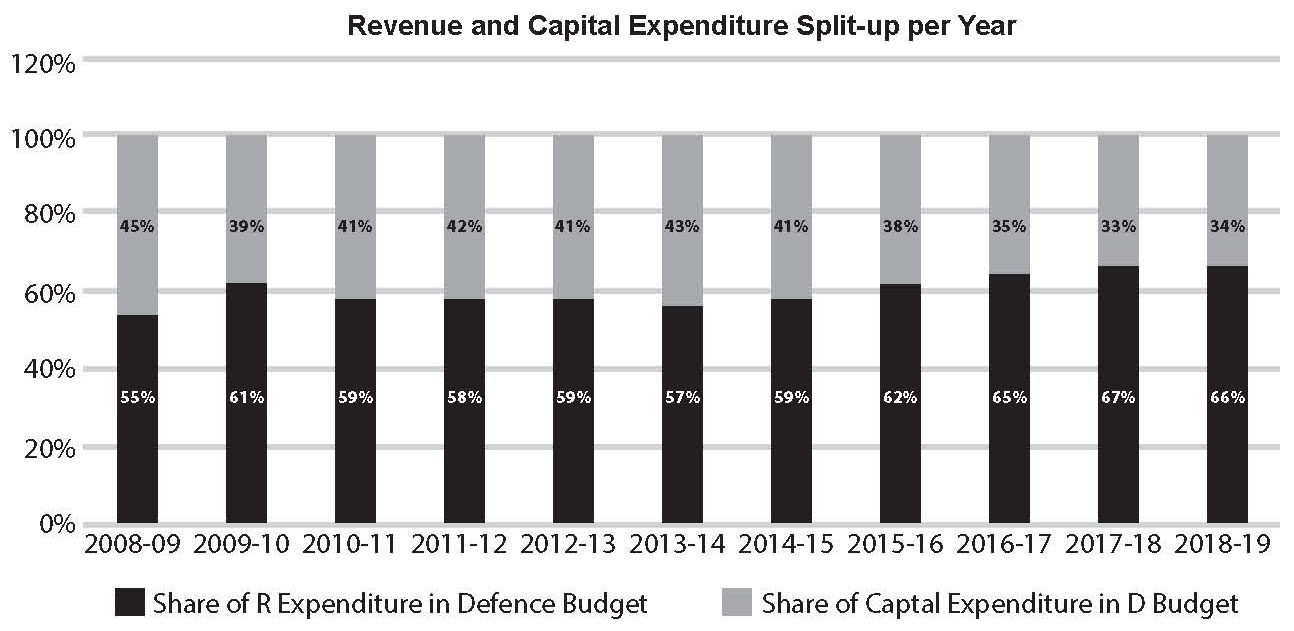

The major problem lies in the area of capital expenditure allocation which this year is barely 34 per cent of the overall budget while revenue expenditure is a high 66 per cent. Over the last ten years, capital outlay has consistently reduced from about 45 per cent to 34 per cent. If the miscellaneous expenses of the Ministry of Defence (MoD) are deducted, the effective capital outlay comes down to around 25 per cent. Over and above this issue, the committed liabilities have increased from 60 per cent to 92 per cent, thus leaving barely eight per cent for new procurements. Similarly, the shortfall in projected requirements has shot up from 11 per cent in 2011 to 36 per cent last year. Fundamentally, India’s procurement policies are crisis-managed, that is we delay or postpone our procurement till a crisis point is reached. When we finally do make the decision for procurement, it is at exorbitantly higher costs, besides the penalty of operational costs and opportunities lost. Indigenous manufacture has rarely moved beyond the licensed-production model. As a result, there are many occasions when the huge infrastructure of the Defence Public Sector Undertakings (DPSU) lie idle because we have not succeeded in putting in place a strategic continuity plan for defence industry beyond the licensed-production model. Production efficiencies are low and there are serious issues of lack of accountability resulting in the capital outlay being spent largely on imports. Considering the fact that the rupee has slipped from 40 to a US dollar in 2005 to 70 today, the increase in capital outlay has not kept pace with rupee depreciation. As a result, there has been a cascading effect of postponing or delaying most procurements due to the huge costs involved. The only way this can be addressed is a combined strategy of higher expenditure of not less than three per cent of GDP on defence and match it with a focussed strategy of indigenisation over the next 20 years.

|

Committed Liabilities Over the Years |

|||||

| Year | Service | Committed Liabilities (CRO RES) | % of Total Acquisition Budget | New Schemes (IN CR) | % of Total Acquisition Budget |

| 2009-10 | Total | 26,316.00 | 60% | 17,500.00 | 40% |

| 2013-14 | Total | 70,489.00 | 96% | 2,956.00 | 4% |

| 2014-15 | Army

Navy Air Force Total |

18,851.26

21,248.07 29,173.40 69,272.73 |

93% |

2,084.16

663.92 2,644.99 5,393.06 |

7% |

| 2015-16 | Army

Navy Air Force Total |

20,513.44

22,248.12 28,246.53 71,008.09 |

92% |

1,541.06

1,112.78 3,264.09 5,917.93 |

8% |

| 2016-17 | Army

Navy Air Force Total |

19,449.26

18,763.77 22,871.05 61,084.08 |

87% |

2,086.00

1,600.00 4,684.97 8,371.00 |

13% |

| 2017-18 | Army

Navy Air Force Total |

20,177.00

18,338.00 30,885.00 69,400.00 |

87% |

2,000.00

4,599.00 4,000.00 10,599.00 |

13% |

Capital expenditure trends have been erratic due to the serious deficiencies in the importance accorded to defence modernisation plans. In almost all years, the Ministry of Finance pays just lip service to the five-year and 15-year plans put together by the MoD after many years of deliberations. Because budget allocations are not carried forward and lapse at the end of the year, most acquisition plans rarely adhere to their original time schedules. This poor planning further complicates the issue with erratic committed liabilities that leaves little for new acquisitions.

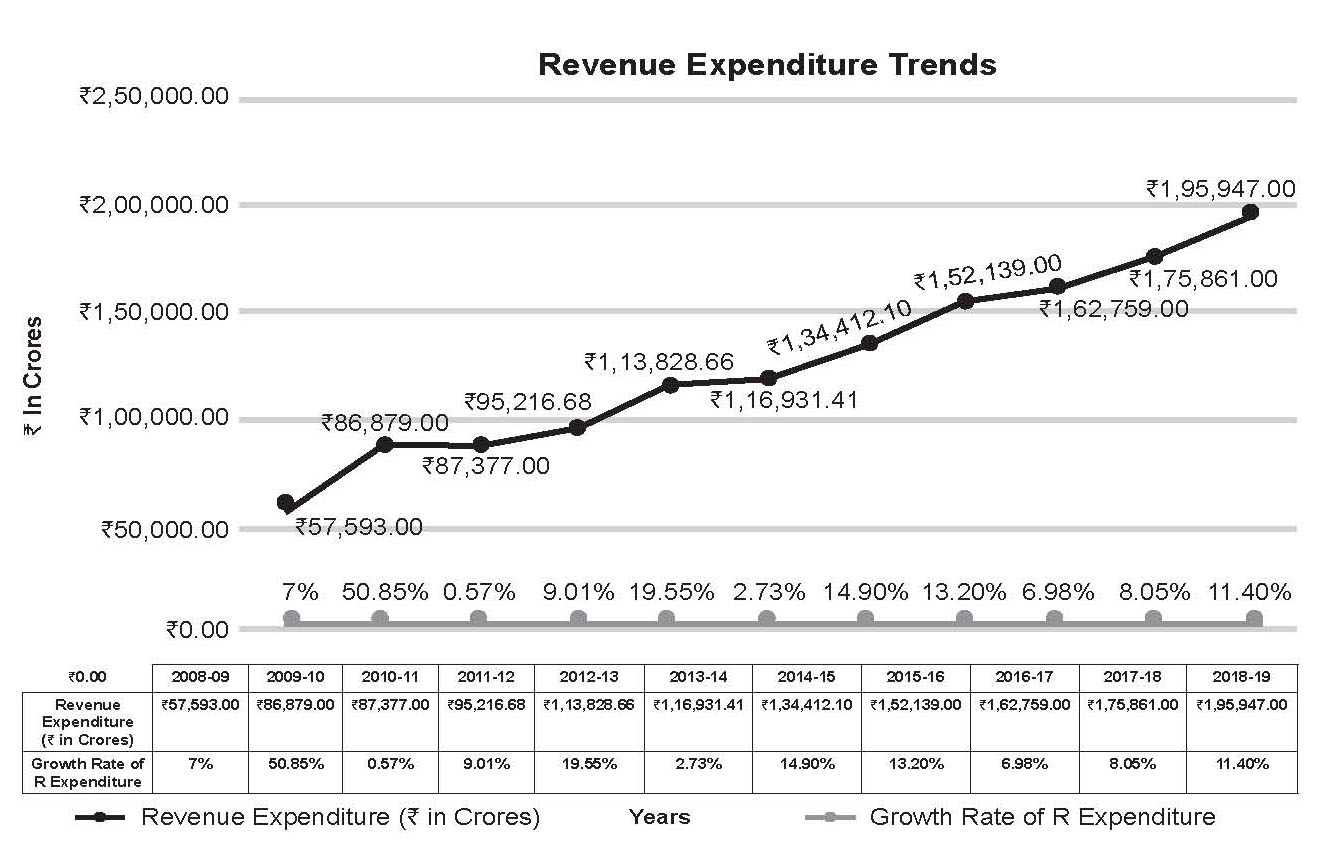

Revenue Expenditure

Revenue expenditures, which include pay and allowances, maintenance and stores, have become nearly 70 per cent of this year’s defence budget. This is a lopsided composition. Pay and allowances are mandatory expenses and periodic increase is mandatory, much like any other department of the government. Similarly, maintenance and stores expenses are routine requirements, which can become expensive if systems are not replaced in time and obsolescent systems are retained in service. Hence, the right approach would be to factor in the revenue component as the basis of defence budget allocation, wherein the revenue component does not exceed 45 to 50 per cent of the budget. Effectively, this would mean that if the revenue requirement of `1,95,947 crore forms 50 per cent of the defence budget, then the right allocation should have been `3,91,894 crore instead of `2,95,510 crore. A higher allocation of 50 per cent or more for capital outlay over a 15-year Long Term Integrated Perspective Plan (LTIPP) period would not only address the modernisation problem, but would put the indigenous industry development on a firm footing. Subsequently, this will lead to a reduction and stabilisation of the defence budget at 2.5 to three per cent. All this will need a change in perception that a well-planned defence expenditure strategy could turn out to be a critical component of the national economy.

Defence Budget Growth – Erratic and Inconsistent

Allocation for defence budget, year-on-year as statistics show, has been erratic. This impacts modernisation plans adversely which in turn has a serious impact on operational preparedness as well as capability projection and credibility. Besides, there has been inconsistency in including or excluding expenditures that quite often may be outside the ambit of the defence budget. For example, in the budget for the financial year 2017-2018, the Finance Minister allocated `2,74,114 crore for defence, whereas, the MoD figure was `2,62,390. The difference of `11,724 crore comes under civil estimates of `85,740 crore which does not form part of the defence budget. Inconsistent growth in defence allocations has indirect adverse impact on the defence industry as well. The pattern for the last ten years is shown in the graph next page.

The idea that defence is a drain on the national economy is a seriously flawed one, if not a traitorous concept. Military preparedness is not just about equipment, personnel and training alone, but more importantly, it needs to be seen from the perspective of defence economy which is a critical component of the national economy. The defence sector involves highly skilled manpower in the military, highly skilled workforce in the defence industry and can contribute significantly through focused R&D. All this will initially need high investments and consistency till we acquire a critical mass in terms of innovation and indigenous development.

On the other hand, piecemeal budgeting creates negative consequences of a stagnant industry and poor operational capability, besides high costs and economic inefficiency. France’s strategy for the development of its military capability and armament industry after the Second World War, serves as an excellent model. While it used imported American equipment and American financial assistance to rebuild its military capability in the late 1940s and early 1950s, it used subsequent ‘Offshore procurement assistance’ from the US to build its armament industries and buy its equipment from those industries. By the early 1960s, the French industry not only fully supported its military, but became a major export earner for the French economy.

The US follows a model of base budget for routine functioning of its Department of Defence (DoD) and the military to meet its operational objectives. It includes salaries, pay increase, maintenance and procurement while all other expenses are added on as inter-related departments’ works, contingencies and others such as nuclear security. The base budget is guaranteed while all others have to be approved as additional contingencies. For the financial year 2018-2019, President Trump has asked for the highest base budget of $597.1 billion, while the total defence expenditure is expected to be $886 billion, which is a whopping 5.1 per cent of its GDP. When pensions and paramilitary expenditures are included, India’s defence budget of $64 billion is still less than 2.5 per cent of its GDP.

Defence Expenditure as a Percentage of GDP

Defence expenditure as a percentage of GDP is more useful when comparing it with other expenditures of the government, provided each of those expenditures are assessed in terms of accountability, efficiency, net outcome and transparency. Using it to compare with the defence budgets of other countries or to say that India has the fifth largest defence budget in the world is meaningless. Defence expenditure must be seen in the context of the nation’s security needs and its larger tangible benefits rather than as a mere expenditure. It is the actual amount spent towards meeting our requirement that matters more than the percentage of GDP.

Much of our modernisation expenditure is still import-dependent. Even those that are manufactured within the country, largely under licence, have high import content. Quite naturally, this high import-dependence renders the Indian military modernisation far more expensive. This import dependency can be reduced only through a concerted long-term strategy through sustained high investments in the initial stages. Unfortunately, the defence budget has been kept at marginal levels and has been declining over the last decade.

China’s defence budget for 2018 is 1.9 per cent of its GDP but we must remember that its economy is five times bigger than ours. The real comparison is that China will spend $278 billion (as calculated by SIPRI) on its defence while India, with security commitments as much as that of China, will spend only $64 billion. Even if we take China’s official figure of $175 billion, it is way above India’s effective expenditure of $44 billion. Russia spends 4.5 per cent of its GDP, while countries like Israel and Saudi Arabia spend five and ten per cent respectively. Quite obviously, defence expenditures are determined not just by security environment alone, but more importantly, by national objectives related to its international role in its own perception. Therefore, defence budget, if it is crafted with a clearly defined long-term national strategy, will address the needs of national capability in terms of military power, technological control and strategic autonomy.

Geopolitics and Defence Expenditures – India & China

Geopolitics is an ever-present factor in the modern international system. With increasing importance of Asia and the Indian Ocean, accentuated by the rapid rise of China, realignment of great powers is a dynamic and continuous process, particularly in the context of rising economies of India and China. India’s defence budget of `2,95,510 crore also includes `18,000 crore for Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) projects. On the other hand, China’s official figure of $175 billion does not include its huge investments in R&D, paramilitary, nuclear, space weapons and other expenditures camouflaged under developmental schemes. SIPRI estimates that China’s defence expenditure is more in tune with its figure of $278 billion and probably even higher.

|

India’s and China’s Defence Budget |

||||||||

| Years | India (USD Billions) | Growth % | China (USD Billions) |

Growth % | Comparison Ratio of China’s and India’s Budget | China (Sipri Estimates in USD Billions) | Growth % | Comparison Ratio of China’s (Sipri) and India’s Budget |

| 2008 | 23.79 | 13.00 | 60.10 | 33.30 | 2.53 | 113.50 | 9.45 | 4.77 |

| 2009 | 31.93 | 34.22 | 70.00 | 16.47 | 2.19 | 137.40 | 21.06 | 4.30 |

| 2010 | 33.20 | 3.98 | 78.50 | 12.14 | 2.36 | 144.40 | 5.09 | 4.35 |

| 2011 | 36.03 | 8.52 | 91.50 | 16.56 | 2.54 | 155.90 | 7.96 | 4.33 |

| 2012 | 40.44 | 12.24 | 106.00 | 15.85 | 2.62 | 169.30 | 8.60 | 4.19 |

| 2013 | 37.40 | -7.52 | 119.50 | 12.74 | 3.20 | 182.90 | 8.03 | 4.89 |

| 2014 | 38.35 | 2.54 | 136.00 | 13.81 | 3.55 | 199.60 | 9.13 | 5.20 |

| 2015 | 40.40 | 5.35 | 141.50 | 4.04 | 3.50 | 214.50 | 7.46 | 5.31 |

| 2016 | 38.00 | -5.94 | 147.00 | 3.89 | 3.87 | 217.80 | 1.54 | 5.73 |

| 2017 | 42.00 | 10.53 | 152.00 | 3.40 | 3.62 | 228.00 | 4.68 | 5.43 |

| 2018 | 44.00 | 4.76 | 175.00 | 15.13 | 3.98 | 278.00 | 18.42 | 6.32 |

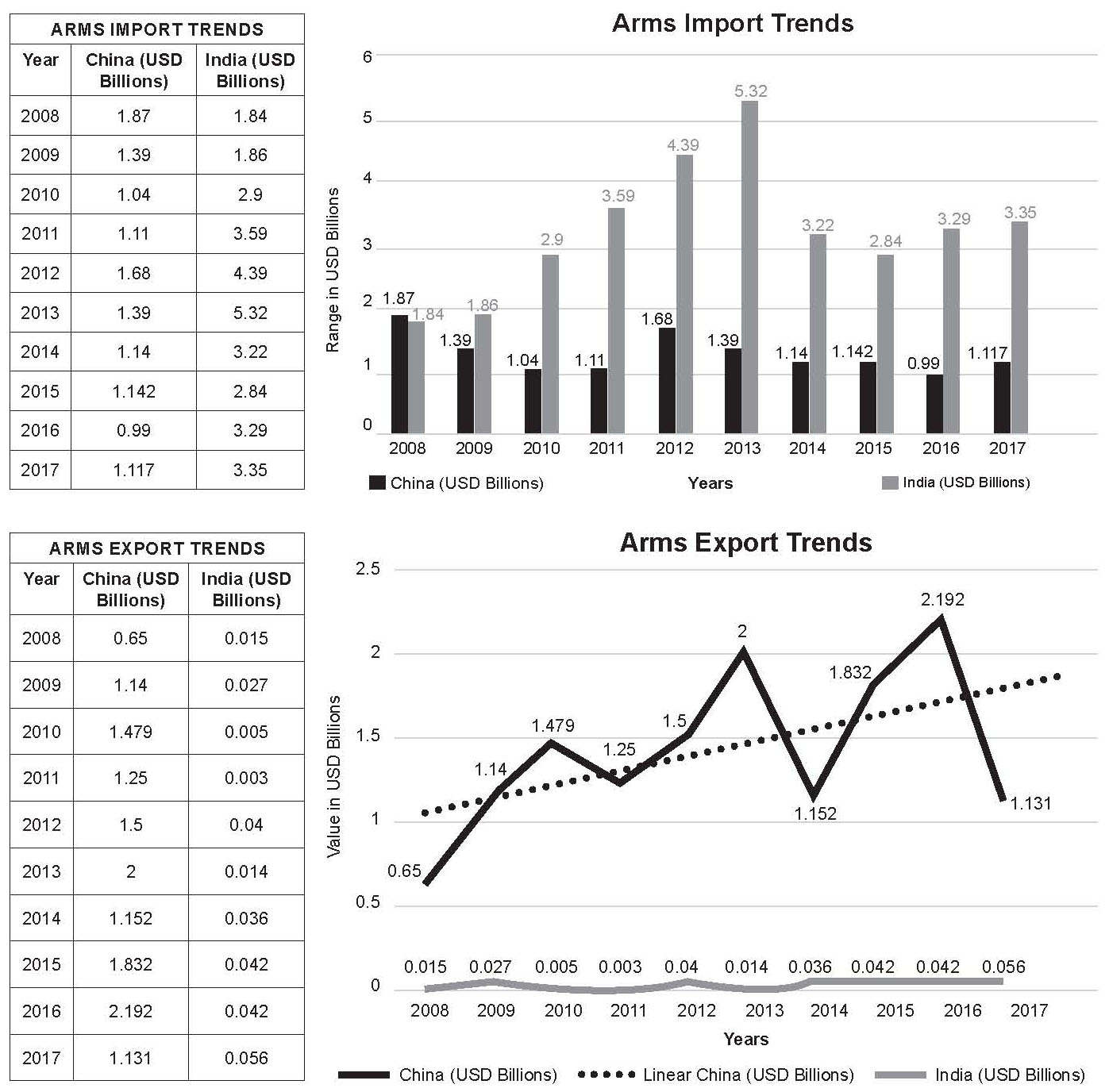

A comparison of India’s defence budget with that of China shows the expanding gap between the two sides. There is also the factor of China’s domestic defence industry that is growing rapidly in capability and scale to support its military modernisation effort. In India’s case, indigenous capability continues to be stagnant, unable to support its modernisation efforts effectively. This is reflected in the huge differentials in the import and export performances in armaments of the two nations. China has invested heavily in its technology and product related developments, with inter-linkages in to the civilian sectors more effectively. The best example is the coupling of its civil aviation R&D with that of military aviation. More importantly, China is quite aggressive in exporting its defence products which were mostly small arms in the past, but has now expanded aggressively with aircraft, ships, weapons and UAVs. Every major defence import of China has subsequently resulted in a significant development of its indigenous capability. The best example is that of the Su-27 which was contracted by China almost at the same time as India’s contract for the Su-30MKI. However, China has rapidly moved onto its indigenous (reverse engineered) J-11 series production, while India’s licenced-production run of Su-30MKI will come to an end in 2020. Export orientation and export performance have a major impact on the country’s defence modernisation.

The Wuhan summit has given fresh impetus to the India-China relationship. However, it must be clearly recognised that China has given nothing away. Its claims on Arunachal Pradesh and its occupation of Aksai Chin has not changed one bit. Similarly, it has got its way with respect to its desired construction in Doklam. Following its theatre command restructuring, China has commenced deployment of significant air assets in Tibet. China’s military modernisation is progressing quite rapidly. Its fighter aircraft and aircraft carrier development and building programmes are progressing at a fast pace. Similarly, China has not slowed down or compromised, in the face of India’s reservations, its implementation of CPEC with Pakistan.

Asia’s security environment is changing rapidly with China’s rise and influence in the Indian Ocean Region. While the new strategic convergence between India and the US is reflected in a series of announcements such as Indo-Pacific, Malabar exercises and the Quad, these will mean nothing if it is not backed by an effective and capable military force structure. The IAF’s rapidly dwindling force structure, the Indian Navy’s long delayed ship-building and submarine-building programmes and the Indian Army’s pathetic state with respect to even its basic weapons such as small arms and protective gear, leave alone long-delayed and never-ending ambitious programmes such as Future Infantry Combat Vehicle (FICV) and BMS do not seem to have alarmed the government sufficiently. No amount of diplomatic skills can become effective unless backed by credible military power. And military power cannot be built overnight as a crisis management. It needs long-term vision and sustained strategic orientation with financial commitment.

Reduction of India’s defence expenditure to an abysmal 1.58 per cent of GDP is the result of a flawed process by the Finance Commission. The 13th Finance Commission, in its endeavour to bring down the Current Account Deficit, did not even consult the stakeholders (MoD and the Services) when it decided to recommend the reduction in defence allocation. The logic that a lower percentage of GDP, in view of India’s economic growth, could meet defence needs is seriously flawed. The Commission decided to forego any efforts at understanding defence issues primarily because it could not cut down any of the politically sensitive subsidies and other so-called social security schemes. In its endeavour to achieve fiscal consolidation, the Committee recommended barely sustainable defence expenditure growth at an annual average of 8.33 per cent. It did not give sufficient thought to various aspects of industry development, import dependency, rupee depreciation and indigenisation strategy. Its objective was to reduce defence expenditure to 1.76 per cent of GDP by 2014-2015. It has now come down to 1.58 per cent of GDP, the lowest since the 1962 War.

Conclusion

Is there scope for India’s defence budget to be more effectively addressed – in short, can the Finance Minister find more funds for capital outlay? If we look at the break-up of the budget, we find that the major share of 24 per cent goes towards states’ share of taxes and duties. This is followed by interest payments at 18 per cent and central schemes at ten per cent. The remaining are the major budgeted expenditures, where defence, subsidies and centrally sponsored schemes are the highest at nine per cent each. The others are pensions at five per cent, finance commission and other transfers at eight per cent and other expenditures at eight per cent. Centrally sponsored schemes, subsidies and other expenditures constitute 26 per cent. Most of these schemes are politically driven and have significant levels of inefficiency and wasteful expenditure with no tangible results. For example, the MNREGA has been counterproductive in rural areas resulting in a death blow to agriculture. Most of these schemes are social security schemes but are afflicted by serious corruption and inefficiency because of which far less than 50 per cent of the allotted funds reach the targeted population. A more effective, transparent and accountable system will free up significant amount of funds.

Similarly, infrastructure development in border regions, though of high priority for the military, is really a development expenditure that should come from infrastructure departments of the States and the Centre. These could really free up significant levels of resources to meet defence expenditure. However, such a transformation in defence budgeting will need boldness and far-sighted vision on the part of the political leadership to take some hard decisions on the strength of their better understanding of the needs of the defence mechanism of the country.