More than a century ago, Alfred Mahan, an influential geo-political figure of the times and a close confidant of President Theodore Roosevelt, strongly advocated the efficacy of ‘seapower’. He viewed the sea in general and the Pacific Ocean in particular as a domain where America needed to exercise its influence. His vision of the Pacific was not only geopolitical but geo-economic as well, where “the convergence there of so many ships…will constitute a centre of commerce, inter-oceanic encounters (between states), one whose approaches will be watched jealously, and whose relations to other centres of the Pacific by the (maritime) lines joining it to them must be examined carefully.” Read Pacific Ocean for the Indian Ocean and one has India’s naval setting!

More than a century ago, Alfred Mahan, an influential geo-political figure of the times and a close confidant of President Theodore Roosevelt, strongly advocated the efficacy of ‘seapower’. He viewed the sea in general and the Pacific Ocean in particular as a domain where America needed to exercise its influence. His vision of the Pacific was not only geopolitical but geo-economic as well, where “the convergence there of so many ships…will constitute a centre of commerce, inter-oceanic encounters (between states), one whose approaches will be watched jealously, and whose relations to other centres of the Pacific by the (maritime) lines joining it to them must be examined carefully.” Read Pacific Ocean for the Indian Ocean and one has India’s naval setting!

The Indian Navy remains weakest in its submarine arm. With most of them being of the eighties vintage, this crucial element warrants immediate attention. Thankfully, even though after much delay, robust plans are in place to strengthen the underwater arm. in 2006, the Indian government cleared a 30-year submarine building program.

Mahan’s “control of a maritime region is insured primarily by a navy, secondarily, by positions, suitably chosen and spaced one from the other, upon which as bases the navy rests, and from which it exerts its strength.” India’s control of a maritime region is to focus on the Indian Ocean, with the waters between the Gulf of Aden and the Straits of Malacca being the immediate “area of interest”. A ‘blue water’ navy serves as India’s primary instrument to achieve Mahanist ‘seapower’. Even around the time India gained independence from British rule, great Indian contemporary scholars like Kavalam Panikker and Keshav Vaidya advocated the need for India to build and project naval power to not only defend her coast but her distant oceanic frontiers as well. In Vaidya’s own words, “the points which must be within India’s control are not merely coastal, but oceanic, and far from the coast itself…our ocean frontiers are stretched far and wide in all directions.” However in strategic terms a “continental mind set” held sway until the late nineties, with a consequent neglect and languishing of the Indian Navy.

Nevertheless, a strong strategic maritime build up has been evident since the late 1990s, with the first concrete initiatives being undertaken by the BJP government of the times which took strong policy decisions to increase funding for warship construction in order to build ‘blue water’ capability for the Indian Navy. This support has been maintained by the subsequent Congress led administrations and facilitated by India’s strong economic performance in the past decade. India’s emergence as an economic power not only ensures more sustainable funding for the Indian Navy but also strengthens concerns for defense of Indian economic interests on the high seas. This push for a ‘blue water’ navy by India is not only connected to establish an extension of the state’s presence but also due to it’s growing economic needs for trade and access to energy resource that necessitate protecting energy sealanes across deep waters. All in all, it means there is a much more overt military and political readiness to build ‘blue water’ capability.

The reasons for this build up are several. First, national prestige has become an important lever for the Indian Navy, the need to have a powerful three-dimensional long-range navy to reflect a Great Power status. Second, the ability of the indigenous shipbuilding industry to not only provide more but also “push” for more (orders). Third, to have a credible “second strike” nuclear deterrent, as a naval retaliatory action is considered least vulnerable and most effective in view of India’s self-declared “no-first-use” policy. Fourth, due to wider external factors concerning India’s various strategic needs and perceived threats. Last, the anxiety to remain competitive vis-à-vis other states, with this aspect being more China centric where geography clearly brings overlapping if not conflicting geopolitical imperatives. Infact, India’s own rise as a naval power has been in part a reaction to China’s ‘blue water’ aspirations where by it feels threatened over being encircled in and around the Indian Ocean. Hence, the “China factor” remains an important dimension in the Indian maritime thinking.

Naval deployments are a readily available and particularly public demonstration of diplomacy, of showing the flag, of showing support, more dramatically and more visually showing India’s presence in an immediate, flexible, and readily redeployable manner.

Stealthy state-of-the-art frigates and destroyers commit themselves to longrange diplomatic deployments, explicitly highlighting India’s naval capability and implicitly showcasing India as a high tech power. Port calls help strengthen diplomatic ties and even though such deployments remain swathed in general talks of ‘win win’ situations not aimed at any particular third party, yet very often the real objective of India’s naval diplomacy is the balancing of China’s influence, not through direct confrontation but by fostering cooperative ‘blue water’ frameworks with nations far and wide in the Indian Ocean and beyond. Central to India’s current strategic thinking is the Indian Ocean, the desire to make the Indian Ocean, ‘India’s Ocean’.

Like Vikramaditya, there might be some slippage in delivery, but not of the final outcome. Indias carrier force is intended to give the country both its flag and force, to show the former and use the latter, should the need arise.

The Indian Ocean is correctly described as part of India’s ‘extended neighbourhood’ and such a theatre where India’s diplomatic, security and economic interests need to be safeguarded by the Indian Navy.

Capability

A concerted building and purchasing program has reshaped the Indian Navy. The results are what the Indian Navy now officially claims “blue water capabilities”. From a service-share of the defense budget of 11.2% in 1992-93 to 18.26% in 2007-08, there has been a distinct momentum in terms of increasing naval expenditure. 20% seems feasible and reasonable in the allocations to come.

Like a true three-dimensional force, the Indian Navy can be divided into 3 components, on the water, under the water, and in the air. On water, India’s aircraft carrier program has been a particularly important high profile element in India’s drive towards ‘blue water’ status. The idea is to have atleast three carrier led battle groups by 2017, with fleets in Arabian Sea, Bay Of Bengal, and the Indian Ocean on same lines as the US Pacific, Atlantic and Mediterranean fleets.

This ‘on water’ element overlaps with the air component which is entitled for a big boost with the induction of the MiG 29K, and the naval variant of the LCA/ MMRCA. With a sea endurance of 30 days and a range of 22,500 km, INS Vikramaditya with its complement of MiG 29Ks (having a range of 2300 km) is going to lend a quantum leap to India’s ‘blue water’ capabilities. Added to this is the impending induction of two indigenous aircraft carriers (IAC I & II) by 2014 and 2017 respectively.

Like Vikramaditya, there might be some slippage in delivery, but not of the final outcome. India’s carrier force is intended to give the country both its flag and force, to show the former and use the latter, should the need arise. With growing indigenous designing and production, other ‘on water’ elements are also coming into their own with an impressive line up of coastal as well as oceanic vessels being added to the fleet. This includes fast-attack crafts, missile boats, patrol vessels, support/ replenishment tankers, landing crafts, minesweepers, and state-of-the-art stealth frigates and destroyers among others.

Maritime missile technology further enhances the Indian Navy’s potency. The 300 km BrahMos medium range cruise missile and the 350 km Dhanush (Prithvi II adapted) ballistic missile being particularly successful additions to India’s armoury. It may be noted here that the Dhanush is capable of being launched from both ‘on water’ as well as ‘under water’ assets.

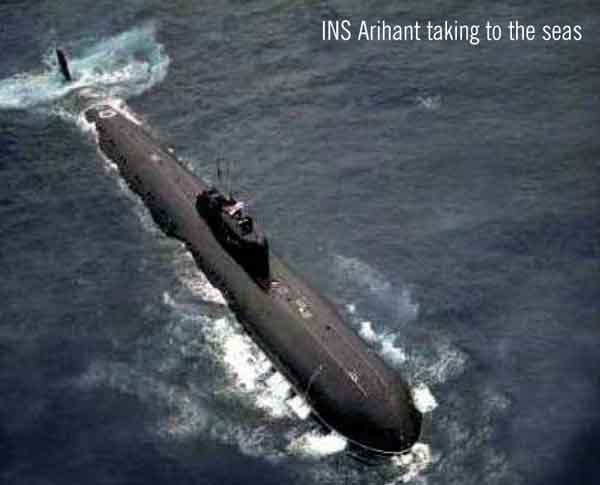

Of great importance is the successful testing and impending installation of 1500 km range Sagarika ‘Oceanic’ missile on the INS Arihant. Add to this India’s successful testing of the 3500 km range Agni III ballistic missile (with work underway for a submarine launched version) and it puts both Pakistan and China even more firmly within India’s nuclear sights. The most powerful leg of the triad is in the navy as it is hidden underwater and moving. All this more or less completes the nuclear triad and gives India a “credible second strike capability”.

The Indian Navy remains weakest in its submarine arm. With most of them being of the eighties vintage, this crucial element warrants immediate attention. Thankfully, even though after much delay, robust plans are in place to strengthen the underwater arm. In 2006, the Indian government cleared a 30-year submarine building program, with the project being kick-started with an agreement being finalized with France for the construction of 6 Scorpene attack submarines at Mazagoan docks, Mumbai. The first of these is expected to be delivered by 2012 with one vessel being delivered every year till 2017. RFPs have also been floated for a second range of submarines.

India’s blue water reach has been displayed by the active deployment of such assets. The Indian Navy’s vision of “Taking to the Blue Waters” has resulted in increased deployments both within and outside IOR, with Indian Navy ships and aircraft being increasingly visible at sea and in ports near and far.

The 4th generation Amur class Russian submarines with their vertically launched Klub-S missiles and the new generation German HDW submarines with their airindependent propulsion system being the leading contenders. The Indian Navy already operates one Russian Akula II class nuclear submarine on a 10 year lease with another one of the similar type to be inducted shortly. The INS Arihant (India’s indigenous nuclear submarine) has already been inducted and is currently undergoing advanced sea trials and should be declared fully operational in the near future.

The government has already given the go-ahead for the indigenous manufacture of atleast 2 more nuclear submarines. There are talks of further boosting the submarine fleet with the total number being placed around 30 by 2025, out of which atleast 6 are intended to be nuclear and the remaining conventional. There are other significant assets that the Navy has already acquired or is the verge of doing so. These include atleast 3 squadrons of the 300 km Israeli Heron II UAVs and 10 P8A spy planes to replace the ageing Tu-142Ms and boost long-range maritime surveillance. Meanwhile, there is also the drive for a satellite networked-force with maritime surveillance to keep tabs on the entire Indian Ocean.

In terms of bases and berthing facilities, traditionally, the command centres for the Indian Navy have been Mumbai for the Western Command and Vishakhapatnam for the Eastern Command, both more geared up for local operations. However, India’s strategic reach has been significantly enhanced by the activation of a deep-sea base at Karwar in Karnataka (INS Kadamba). This base opens the gateway to the depths of the Indian Ocean. This is further complemented by the development of a naval airbase at Uchipulli, near Rameshwaram, which enables better monitoring of the entire Indian Ocean Region (IOR). In the southern oceanic depths, the activation of a monitoring station by the Indian Navy, with some anchoring facilities, on the northern tip of Madagascar in 2007 was another symbol of India’s new found infrastructural reach.

There are also talks of developing maritime infrastructure for the Indian Navy on the Mauritian Island of Agalega. Meanwhile, the setting up of the Far Eastern Naval Command (FENC) at Port Blair further lends the Indian Navy with ‘blue water’ status as it enables longer range operations in the Bay of Bengal, Malacca Straits and further eastward. Plans have also been announced to construct another deep water base 50 kms south of Vishakhapatnam to further increase India’s naval presence in the Bay of Bengal and IOR and to counter China’s influence in the region. There is also news of delicate talks with Vietnam for naval berthing rights for Indian ships at Cam Ranh deep water bay.

Deployments

Bolstered by her growing capability, India’s ‘blue water’ reach has been displayed by the active deployment of such assets. The Indian Navy’s vision of “Taking to the Blue Waters” has resulted in increased deployments both within and outside IOR, with Indian Navy ships and aircraft being increasingly visible at sea and in ports near and far. Such deployments showcase to the world the maritime, economic and technological prowess of the nation with these modern and sophisticated ships projecting a brilliant picture of a militarily strong, vibrant and confident India. In other words, a ‘blue water’ navy that is firmly plugged into the security politics of the Indian Ocean.

In terms of deployments, IOR has seen long-range Indian surveillance and operations from the Gulf of Aden to the Straits of Malacca and even deep south towards the Mozambique channel. In the western reaches of the Indian Ocean, Indian ships operate far and wide in the Arabian Sea with countries like UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, Iran et al being a part of either joint exercises or port calls. This naval presence is an essential part of India’s ‘Look West’ policy announced in 2005. The Gulf of Aden has also seen ongoing Indian surveillance and joint exercises with friendly Russian and French flotillas near Socotra and Bab-el-Mandeb entrance to the Red Sea respectively. India’s presence around that choke point was again demonstrated with maritime patrols picking up Chinese ships soon as they emerged from Red Sea in March 2006, India keeping a vigilant eye some 2300 km away from its own mainland.

Further naval projection has also been witnessed in the distant Mediterranean with Indian destroyers and tankers visiting ports in Israel, Cyprus, Egypt and Turkey. In the southern reaches of the Indian Ocean, maritime links are evident with Mauritius with talks of basing rights at Agalega island. The Indian Navy is also responsible for monitoring Mauritius’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Towards the south-western tangent, Indian ships have ventured the African coast towards Mozambique and South Africa, with trilateral exercises being conducted along with Brazil and South Africa.

Although the Indian Navy has the governments approval to maintain certain force levels, they will steadily keep reducing till 2012 because of the ships being decommissioned will outnumber the new ones being inducted.

In the eastern reaches the FENC has been the ‘springboard’ for ‘blue water’ deployments with exercises being conducted with the navies of Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mayanmar, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Philippines, South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Singapore, New Zealand and even the Americans. India’s naval deployments have particularly gone far eastwards with the immediate gateway being the Malacca Straits with trade, energy access and balancing China being the main objectives.

Conclusion

Although the Indian Navy has the government’s approval to maintain certain force levels, they will steadily keep reducing till 2012 because of the ships being decommissioned will outnumber the new ones being inducted. However, the silver lining is that the new vessels that are being inducted are very sophisticated, much more stealthy and have considerably longer range of operations.

This is transforming the Indian Navy into a much leaner and meaner fighting machine and also correcting a force imbalance by replacing smaller ‘brown water’ ships of limited capability with much more capable ‘blue water’ assets. The trend is clear, with sustained longterm projects in place now delivering the required elements. Such purchases and constructions are giving India more and more tangible ‘blue water’ capacity and enabling the Indian Navy to fulfill its strategic purpose of ‘blue water’ power projection.

Consequently, India is set to be a significant player in the global maritime pecking order for the coming century, with a substantive ‘blue water’ navy now operating in various long range deep water settings.

Courtesy: Salute Magazine

Excellent article Sandeep Sethi.

Keep up your enlightening detailed articles like a layman , soft ware enginner , like me.

thank you so much.

~Sha