Till the liberation of Bangladesh, India never had a military victory in the previous ten centuries. Indian history is replete with repeated defeats, humiliations and subjugation by more enterprising invaders. Invariably, the Indian forces deployed in successive battles were numerically superior to the invaders, but despite that they never won. As a result the country remained under foreign rule, shackled for years in slavery. Against this background, Bhutto once remarked in one of his characteristic postures of bellicosity: “India should not forget centuries of her history.”

Why did India lose? Firstly, there was a lot of infighting which did not enable it to put up a united front against the invader. Secondly, Indian military leadership was always outwitted by the invader’s superior tactics and ability to manoeuvre. The Indians were committed to orthodoxy, while the invaders always brought about the unexpected in battle, and this swayed the fortunes of war in their favour. Thirdly, the Indians lacked staying power, which often turns apparently lost battles into victories. The invaders lasted a little longer to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat.

Since independence, India has seen three conflicts with Pakistan and one with China. Against Pakistan all three wars ended in stalemate, while India was humiliated by China. Within our short span as a free nation the Indian military leadership failed to bring these wars to a successful conclusion. Inconclusive wars have led to others, and will go on doing so till some decision is reached in battle with Pakistan.

Indian military leadership was always outwitted by the invaders superior tactics and ability to manoeuvre. It must be realised that if our political and economic leadership fails it can be replaced by the processes of democracy. But if our military leadership fails this results in defeat and humiliation. The difference between defeat and victory in battle is that between honour and insufferable dishonour, and there is no middle meeting ground between the two. It becomes imperative therefore for a nation to seek such military leadership as brings victory in battle.

In old wars of the type of World Wars I and II there was sufficient time for the problem of military leadership to sort itself out. It was found that the hierarchy created by the unsatisfactory peacetime selection system proved incapable of handling problems of any magnitude that arose in the crisis of war. Its members were generally replaced by more progressive leaders as the war progressed. In the end, the fittest survived and brought about the much-sought-after victory.

The outmoded selection system was thrown overboard in war as performance in battle became the sole criterion for advancement. When things went wrong, heads rolled ruthlessly. As a result, by the end of the war, the adversaries had the best available leaders in battle. Unfortunately, in the context of present-day short wars, it cannot be left to war to sort out the leadership problem.

In view of the intensity of war and the tight time schedules, usually those in the saddle ride the horse all the way. So if our initial placing is poor the result is disaster. No country, much less India, can afford to take this risk. It therefore becomes necessary for the very best available military talent to be kept at the top all the time to be ready instantly for coping with short wars. But where and how do we find such leaders?

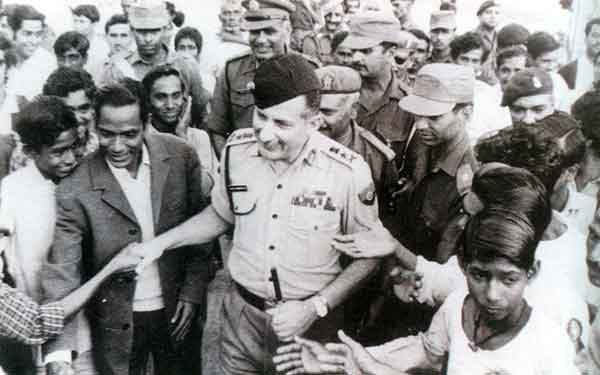

In a talk Manekshaw once said: “You can import the very best of weaponry and equipment, but you cannot import leadership.” What he meant was that the conduct of war is a serious business and needed dedicated professional soldiers at all levels to run it. This business cannot be left to a collection of incompetent and servile individuals who find their way to the top for considerations other than professional and genuine national interests. It is essential that avenues for higher command for such incompetent individuals should be barred by foolprocf systems of elimination and judicious means of selection.

Within our short span as a free nation the Indian military leadership failed to bring these wars to a successful conclusion. The services require three distinct levels of leadership. The first is the level of execution, which is confined to the unit command level. This is really a functional level, where platoon, company and unit commanders are in close touch with men and equipment, and it is on their performance in battle that the fate of an operational plan depends. This level calls for a sound-professional knowledge of weapons and skill in handling them, use of tactical ground and battle drills.

On the leadership side, a personal style which motivates a group to follow their commander in the face of death is required. Precept and example in facing the stresses and strains of crises, especially in physical courage and manpower management, assume great importance. The will to stick it out when things go wrong is necessary, and so is initiative, but at this level it is more essential to obey implicitly than to think for oneself.

Promotion up to this level is by a selection board based on annual confidential reports. Unless there are some disciplinary grounds, every officer should hope to make a unit commander or at least gain a lieutenant colonel’s rank. Most gallantry awards are won up to this level. But excellence in performance or winning awards does not automatically entitle an officer to aspire for higher rank. In World Wars I and II some of the best commanding officers never made brigadier ran. Promotion depends on potential and not just demonstrated performance. In the Indian Army decorations have paved the way for quite a few to attain higher command. Kaul suddenly called for replacement of the divisional and brigade commanders in NEFA after the initial debacle against the Chinese in the battle of Namka Chu. He bid for highly decorated soldiers, and the result was equally disastrous. The Indian formations ran helter skelter without giving the enemy a fight.

Little did Kaul realise that these officers were decorated as company or battalion commanders, and their level of competence ended there. As formation commanders, they had no concept of battle and amply proved that the qualities of leadership required at a higher level are quite different from those at the execution or functional level. The level between subaltern and lieutenant colonel is a nursery for higher command. At this stage, the officer is professionally educated and given an opportunity to handle responsibility appropriate to his rank and experience, and even beyond if found suitable. The young officer must go through a series of career courses of his own arm in his first five years of service so as to enhance his utility in handling subunits of the arm. More promising ones graduate to all arms courses, where an officer is made aware how his own arms, functions dovetail with others in battle. This knowledge enables him to seek the support of other arms and to assess the quantity and mode of such support in a particular situation.

It therefore becomes necessary for the very best available military talent to be kept at the top all the time to be ready instantly for coping with short wars. In the first ten years of his service, an officer has in addition to pass promotion examinations at various stages to entitle him to rise to the rank of captain or major. In the process of an officer’s professional education, the Defence Services Staff College course assumes great importance as it is there that he gains knowledge of inter-service cooperation besides learning staff duties and the logistic aspect of handling formations in war. Vacancies in each course are limited, and to give a chance only to the deserving a yearly competitive examination is held in which the first 20 or so vacancies are allotted on merit and the remainder by nomination from among qualified candidates. The system is a copy of that followed in most Western armies.

This method was satisfactory so long as the Indian Army followed it in letter and spirit. It gave a fair chance to candidates, in that the deserving secured a place through merit and there was no heart-burning in any quarter. It also gave the right to the authorities to nominate trainees on the basis of any criteria they deemed fit. Since these criteria were not made public, it gave leverage to the authorities and some room for manipulation. This was however accepted as a fair system as nomination had to be made from only those candidates who had qualified fully in-the competitive examination.

Sometime in 1963, Bewoor, on taking over as Director of Military Training, realised that by this method a greater percentage of officers belonging to other arms were securing vacancies in fair competition compared with infantry officers. He wanted to control the entry of other arms to the Staff College and make it easier for infantry officers to do so, albeit with artificial propping. He argued that if the avenues for qualifying for higher command were not blocked at this stage, a predominant number of non-infantry officers would in the. long run command infantry formations. He felt this should not be allowed in an army in which infantry predominated.

Since these criteria were not made public, it gave leverage to the authorities and some room for manipulation. This was however accepted as a fair system as nomination had to be made from only those candidates who had qualified fully in-the competitive examination.

To achieve this, he argued that the poor infantry officer remained on picquets perched on hilltops for two or three years in inhospitable areas without electricity and facilities for serious studies. As such, the infantry officer deserved consideration for his inherent inability to compete with officers of other arms in open competition. But the real problem lay elsewhere. Other arms officers, to learn their job of supporting infantry and armour, had to know the detailed characteristics of infantry weapons and their employment. For instance, an artillery battery commander, a major, has to deal with infantry problems at the battalion level with his OC, a lieutenant colonel, while a regimental commander has to deal with a commander at the brigade level, that is one level higher at each rank.

Thus the vision of an officer of another arm stretches beyond his own sub-unit to a higher plane of larger units and formations. By virtue of constantly working with infantry, the officers of other arms understand the handling of combined combat groups, comprising all arms, better than an infantry officer, whose vision never stretches beyond his immediate surroundings and thinking not beyond the range of small arms, which is very little. Not lack of facilities but just lack of comparative competence marred an infantry officer’s chances.

Unfortunately, Bewoor carried the Chief and some overzealous Army commanders with him, and it was decided ill advisedly that opportunities would be afforded to infantry officers by reserving Staff College vacancies on the basis of the overall numerical strength of the infantry. This virtually equated the infantry with the backward classes needing protection under the Indian Constitution.

This gained cheap popularity for self-appointed protagonists of the infantry, but it eventually did great harm to the service. It denied the Army and the nation the services of the best talent they could throw up. By giving unfair advantage to the infantry it blocked the career prospects of brighter officers of other arms.

This fellow Sukhwant Singh appears to be a boderline khalistani case. He has only derogatory articles and comments of the IA and its leadership ever since independence. He is also displaying his true nature which is unfortunately predominant in people of his community which in Army is called the Sardar networking. It does not take a rocket scientist to note that he makes only disparaging and derogatory comments to all the IA leadership EXCEPT those of his own community. He goes out of his way to either potray his own community as great leaders or ones that had great potential but couldnt make it to higher ranks due to victimisation.Sukhwant Singh firstly needs to have a self-reappraisal of his biased mindset and in fact needs to be put on a watchlist as a boderline khalistani case. He cuts and pastes incidents and modifies history to suit his own namakharam agenda for reasons best known to him. He certainly needs to be kept an eye upon to prevent spreading his biased negative propoganda of our respected armed forces and its leadership.

“…It would be fun to confront some higher commanders in our services about opinion about them….”

Are you for real, Major General???

– So are you in this for some sort of impish fun (very unbecoming of your rank) or was this article written in genuine inquisitive and critical spirit??

– As a senior officer, you will be well aware that the Armed Forces do not exactly function in the principles of a country club management that you seem to be so vociferously espousing.

– Very disappointed with this article – definitely not worthy of being hosted in this otherwise distinguished forum.