The usage of the term, ‘war’ when battling terrorism or insurgency raises several issues. An important one is the use of the term ‘victory’ to delineate the desired objective in this conflict. There are vital differences between terrorism and insurgency and they cannot be clubbed together. Nevertheless, security forces have to root out this menace to modern societies. Talk and discussion should not be couched in terms of victory but as objectives to be achieved, as there are always dissenters against societal norms, who need to be accommodated within the mainstream. The conflict is not a zero-sum game. It needs a deeper understanding of the nature of the problem, especially in the Indian context.

‘War’ comes in many shapes and forms, has many different contexts, and is subject to diverse cultural influences. A paradigm shift in the nature of conflict is underway. People fight when they feel that (a) they can accomplish their objectives by force; (b) they feel that there is no alternative to their cause except the use of force; or (c) religion has swayed their ideological thinking into the notion that their cause is just. This has given a rise to terrorism and insurgency, which are the dominant threats we face today and are likely to face over the coming decades. It is a conflict where no one conception of the enemy is accurate, and it is a campaign which sees no decisive battle or an unconditional surrender by the vanquished. The threats are non-traditional, asymmetrical, and insurgent-terrorist in character.

“Mans mind, once stretched by a new idea, never regains its original dimensions.” ““ Oliver Wendell Holmes, 1809-1894

The change in the nature of warfare has led to the idea that the concept of victory in such a scenario is elusive. We face an uncommon terror campaign, a jihad aimed at the national jugular, coupled with ongoing insurgency campaigns. We may have difficulty identifying our moment of victory, but our defeat would not go unnoticed. There is a problem in definition. When we define terrorism as a violent criminal activity done to further some ideological goal, we will never be rid of it. Criminals – with and without ideological pretensions – will always be with us.

Defeating an enemy on the battlefield and forcing it to accept political terms is the traditional way of winning a war. One almost always defines victory as the juncture when one party surrenders to the other. The extent of the victory depends on what the vanquished is willing to give up in order to getting the victor to stop fighting. Secondary objectives also help set the targets for what it means to attain victory, and establishing what victory will mean at a particular time.

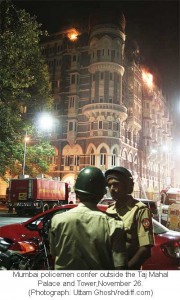

To try and define “victory” in the current struggle, we must understand why this is a war. The coordinated attacks at Mumbai on 26 November 2008 targeted our institutions of political, economic and financial power, and inflicted damage far beyond the loss of life or property. Beyond that, the scope of the malevolent purpose exceeded the objectives of the perpetrators of the violence. The real target of the attacks was the very infrastructure of Indian secular civilization. The nature of terrorism thus metastasizes into an ideology-driven assault on society.

Purpose always matters. As Oliver Wendell Holmes once said, ‘even a dog knows the difference between being stumbled over and being kicked’.1 Islamic terrorism is a coordinated and potentially effective series of attacks designed to destabilize, neutralize, demoralize, disrupt or destroy the support systems of the target civilization. What we are now experiencing is a major scale escalation of terrorism fueled by a single ideology with the goal of destabilizing India.This jihad is kept alive by passive or active state sponsorship, the infiltration of indigenous support systems within target states (including our own), and the establishment of stand-alone bases of operations, within the territory of nation-states hosting such groups and where they claim that they exert no effective authority. These terrorist groups have utilized, and still need facilities, finance, materiel, and logistical support of a kind and scale essentially unobtainable without the overt or covert cooperation of sponsor nation-states, which provide territory, funding and cover – and are part of the terrorist pipeline.

Purpose always matters. As Oliver Wendell Holmes once said, ‘even a dog knows the difference between being stumbled over and being kicked’.1 Islamic terrorism is a coordinated and potentially effective series of attacks designed to destabilize, neutralize, demoralize, disrupt or destroy the support systems of the target civilization. What we are now experiencing is a major scale escalation of terrorism fueled by a single ideology with the goal of destabilizing India.This jihad is kept alive by passive or active state sponsorship, the infiltration of indigenous support systems within target states (including our own), and the establishment of stand-alone bases of operations, within the territory of nation-states hosting such groups and where they claim that they exert no effective authority. These terrorist groups have utilized, and still need facilities, finance, materiel, and logistical support of a kind and scale essentially unobtainable without the overt or covert cooperation of sponsor nation-states, which provide territory, funding and cover – and are part of the terrorist pipeline.

The campaign against such a threat requires an unflinching willingness to inflict and to take casualties. In turn this calls for clarity of purpose, consistency and the capacity for occasional ruthlessness. A willingness to act boldly to punish terrorist cooperation, even on insufficient intelligence (and intelligence is always insufficient) is a very effective deterrent in itself.

Martin Van Creveld wrote as early as the late 1980s that inter-state war was a thing of the past, and that insurgencies and similar sorts of conflicts would constitute the future of warfare, and that militaries that ignored these facts were doomed to obsolescence.2 State failure and criminal instability rather than inter-state war poses the principal security risks of the future.3 A decisive victory is an indisputable military victory of a battle that determines or significantly influences the ultimate result of a conflict. It does not always coincide with the end of combat. There is, therefore, a need to define the concept of victory properly in terms of objectives to be achieved. “The guerrilla fights the war of the flea, and his military enemy suffers the dog’s disadvantages: too much to defend; too small, ubiquitous and agile an enemy to come to grips with.”4

The Existing Situation

South Asia is a key jihad theatre. Afghanistan was the principal Al Qaeda sanctuary until October 2001. A symbiosis developed between the Taliban government and numerous Islamist groups which shared facilities, and allied themselves, with Al Qaeda. Prominent among these was Lashkar-e-Toiba, which since the fall of the Taliban has become Al Qaeda’s principal South Asian ally. The Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP) and Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) on the Afghan-Pakistan border have become a haven for the Al Qaeda, who are cooperating with the Taliban remnants fighting as insurgents in the area. Pakistan itself has experienced Islamist subversion, agitation and terrorist activity, as has India. The ongoing insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir has been infiltrated by Islamist elements and Kashmir has become a major training and administrative area for Al Qaeda affiliates. The neighboring republics of former Soviet Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan) and the Xinjiang Uighur region of China have also seen Islamist subversion, terrorist activity and low-level insurgency.

A willingness to act boldly to punish terrorist cooperation, even on insufficient intelligence (and intelligence is always insufficient) is a very effective deterrent in itself.

It is now increasingly clear that a hard-line view of the Kashmir issue is ingrained increasingly in the religious as well as the political identity of Pakistan. Also, the Pakistani military considers the Kashmiri insurgent organizations to be a key asset, which they will not want to surrender.

The Muslim community in India is a huge group which, for the most part, is not talking about explicitly religious issues and is not a part of the international jihadi circuit. Most Indian Muslims primarily are concerned with local issues rather than Islamic world issues.

Several experts and analysts believe that conflict between two states can exist at lower levels indefinitely without much danger that such tensions will escalate into nuclear war. Many deterrence optimists suggest that third party intervention will always occur during a crisis and is consequently a major factor that will prevent escalation from getting out of hand. Therefore, while brinkmanship is ongoing in South Asia, every Indo-Pakistani war came as a surprise to one of the countries.