As a rising power that detests competition, China might continue to test India’s resolve and patience through pinpricks on the border issue while progressively enhancing the level of engagement on the economic front and cooperating over global environmental concerns. In all likelihood, China will continue to promote activities that militate against the security interests of India. It is in light of these developments that the capabilities of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) must be assessed. Is the PLAAF finally spreading its wings? Does its sustained modernisation drive over the last two decades pose new challenges for India?

Two recent statements by Indian political leaders reflect the current state of Sino-Indian relations. On November 30, 2011, the Indian Defence Minister AK Antony admitted that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had created some, “situations along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) that could have been avoided but which were due to different perceptions of the border.” Although the borders remain un-demarcated, disputes have been managed through established mechanisms such as hotlines, flag meetings and meetings of commanders of both sides. Consequently, the Sino-Indian border has been quiet and tranquil. On December 04, 2011, Omar Abdullah, the Chief Minister of Jammu & Kashmir expressed concern over Chinese involvement in the Kashmir region and urged India, “to show more spine” while dealing with China.

In the recent past, China has taken strong objection to oil exploration by India in collaboration with Vietnam in the South China Sea. The Indian Prime Minister has stated that this is purely a commercial activity in the ambit of international law and has clearly signalled India’s resolve to continue with the exercise.

It should be evident from the above that in the foreseeable future, Sino-Indian relations might be troubled and problematic. As a rising power that detests competition, China might continue to test India’s resolve and patience through pinpricks on the border issue while progressively enhancing the level of engagement on the economic front and cooperating over global environmental concerns. In all likelihood, China will continue to support Pakistan, a policy that would militate against the security interests of India. It is in light of these developments that the capabilities of the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) must be assessed. Is the PLAAF finally spreading its wings? Does its sustained modernisation drive over the last two decades pose new challenges for India?

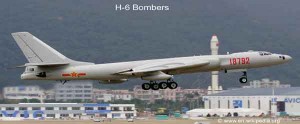

In September 2010, the PLAAF deployed six H-6 bombers escorted by two J-10 fighters to Kazakhstan during the Shanghai Cooperation Organisations (SCO) Peace Mission 2010 exercise. In October 2010, the PLAAF sent four J-11 (Chinese version of the Su-27) supported by one Il-76 aircraft to Konya in Turkey to participate in the Anatolian Eagle 2010, a bilateral exercise. The contingent staged through Iran which provided the required transit facilities. This was the first time that the PLAAF had deployed its air assets at such a distance from the Chinese mainland and engaged in an exercise with a NATO member nation. There were fears in the US about the potential of Transfer of Technology, particularly since Turkey operates F-16 fighters acquired from the US. Turkey, however, assured the US that no such transfer would take place.

In September 2010, the PLAAF deployed six H-6 bombers escorted by two J-10 fighters to Kazakhstan during the Shanghai Cooperation Organisations (SCO) Peace Mission 2010 exercise. In October 2010, the PLAAF sent four J-11 (Chinese version of the Su-27) supported by one Il-76 aircraft to Konya in Turkey to participate in the Anatolian Eagle 2010, a bilateral exercise. The contingent staged through Iran which provided the required transit facilities. This was the first time that the PLAAF had deployed its air assets at such a distance from the Chinese mainland and engaged in an exercise with a NATO member nation. There were fears in the US about the potential of Transfer of Technology, particularly since Turkey operates F-16 fighters acquired from the US. Turkey, however, assured the US that no such transfer would take place.

All three branches of the PLA have carried out numerous exercises in the last two decades. It was in the 1990s that the PLAAF was, for the first time, accorded the authority to “coordinate a joint exercise opposite the Taiwan Strait” signalling the intent of the PLA to play a dominant role. Most of the exercises conducted inside China involved joint operations, para-drop, strategic lift and operations from satellite airfields. The strategic lift exercise, Stride 2009 involved the movement by air and surface transport of a division plus strength of troops from the East to the far end of the country in the West. In the absence of detailed information, it is difficult to accurately assess the actual offensive potential of the PLAAF but emphasis on Rapid Reaction Units, education, joint and Special Forces operations, computer education, increasing reliance on space-based systems and synergy with cyber operations show that the China is serious about transforming its air force to enhance its reach and firepower.

Undoubtedly, the PLAAF has come a long way since the 1970s when it possessed some 5,000 aircraft, a mix of different types. However, only a few of those were really airworthy or posed any threat to China’s neighbours. When the PRC sent a Chinese Volunteer Army consisting of some six corps to fight in the Korean War, only a few pilots in the PLAAF were able to fly the Soviet MiG-15 against the American F-84, and later the F-86 Sabre fighters.

Aviation Industry in China

The threat of an American attack by nuclear weapons forced Mao Zedong to redouble China’s effort to develop nuclear deterrent capability with the necessary delivery systems. Although Russia helped China build a vast defence industry fashioned on the Soviet model, the PLAAF continued to suffer from ‘short legs’ or limited range and armament. During the 1950s and 1960s, operating in concert with Taiwanese forces, the US aircraft and warships regularly violated Chinese airspace and territorial waters. The PLAAF was too weak to retaliate. The focus of the PLAAF was air defence for which, despite their limited range, the Soviet-designed MiG-15, MiG-17 and later MiG-19 served the purpose. First generation Surface-to-Air Missiles, SAM II Guideline even shot down a few USAF U-2 spy planes. The PLAAF also manufactured the Il-28 light bomber and obtained the design of the Tu-16 long-range bomber but by then, relations between the two countries soured and almost all cooperation with the Soviet Union in the defence sector came to a halt.

Efforts were made to design and develop indigenous aircraft but due to China’s inability to manufacture suitable aero-engines, projects languished for years. However, it goes to the credit of Chinese engineers that despite the constraints, they succeeded in cloning the MiG-21 designated as the J-7/F-7 and also developed the J-8, a twin-engine variant of the MiG-19. In fact by 1984, China had already exported this highly agile and easy-to-maintain Chinese version of the MiG-21 to Iraq and other friendly countries.

Efforts were made to design and develop indigenous aircraft but due to China’s inability to manufacture suitable aero-engines, projects languished for years. However, it goes to the credit of Chinese engineers that despite the constraints, they succeeded in cloning the MiG-21 designated as the J-7/F-7 and also developed the J-8, a twin-engine variant of the MiG-19. In fact by 1984, China had already exported this highly agile and easy-to-maintain Chinese version of the MiG-21 to Iraq and other friendly countries.

The 1991 Gulf War came as a wake-up call to China. Her leadership suddenly realised that a nuclear deterrent alone was not enough when pitched against a modern air force that could blunt the capability to retaliate. What followed was the doctrine of ‘active defence’ that implicitly allowed even a pre-emptive strike and a renewed search for modern aircraft and weapons.

The PLAAF has some 1,687 combat capable aircraft up from 1,653 the previous year.Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia was in serious economic difficulties. With her economy already booming, China immediately cashed in on the opportunity and signed a major deal for the purchase of 24 Su-27, roughly in the US F-15 class with the provision for the local manufacture of another 200 aircraft. China also purchased large numbers of Rolls Royce Spey-200 engines from the UK for the locally developed JH-7/FB-7 fighter bomber, accessed high technology from Israel and also purchased Russian aero-engines the RD-93 and Al-31 F to kick-start two other local fighter programmes. What emerged was the JF-17 Thunder co-produced with Pakistan and the J-10 based on the Lavi, an Israeli-designed fighter of the F-16 class. The Lavi programme had been abandoned by Israel supposedly under pressure from the US. Pakistan, incidentally, had allegedly supplied a crashed F-16 and a dud American Tomahawk Air Launched Cruise Missile to China to facilitate reverse engineering.

In less than two decades, the PLAAF has ‘leap-frogged’ two generations to reach a level significantly higher than where it was in the 1980s. Belying Western forecasts, China had deftly utilised her economic and diplomatic clout to transform the PLAAF into a modern air arm.

Not only did China focus on fighter aircraft but also developed, built, and wherever possible, blatantly copied the numerous designs of air-launched weapons and missiles, transport aircraft, helicopters and UAV/UCAV that were obtained from Russia and other countries. Flush with funds, China could get whatever she wanted from Russia. However, attempts to locally manufacture a cloned version of the Al-31F turbo-fan engine that powers the Su-30 have not as yet succeeded. Most China watchers believe that this feat could be achieved in the next few years. China would then have joined the elite club of nations with the capability to manufacture modern jet engines.

The venerable An-12 (Y-8) has been successfully modified into an AEW&C version with more powerful engines, new propellers and modern avionics. The WZ-10 is a locally produced armed/attack helicopter. Some 100 H-6, the Chinese version of the 1950s vintage Tu-16 bomber, modified, with more powerful Russian D-30KP engines, are still operational. This old bomber is now employed for roles such as flight refuelling, electronic surveillance and to deliver anti-ship cruise missiles while remaining out of harm’s way.

The Chinese have also test flown the J-20, their fifth-generation stealth fighter and are confident of inducting it into service by the end of the decade.