Public opinion in China rarely witnesses apprehensions regarding key projects launched by the central leadership. However, over the past few months, Chinese experts – including academics and former diplomats – have expressed concerns regarding the slow progress and challenges faced by the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Some have even questioned the very rationale of implementing the CPEC. Meanwhile, curiously, Pakistan’s Lt General Aamir Riaz called on India to join the CPEC, in December 2016.

Public opinion in China rarely witnesses apprehensions regarding key projects launched by the central leadership. However, over the past few months, Chinese experts – including academics and former diplomats – have expressed concerns regarding the slow progress and challenges faced by the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Some have even questioned the very rationale of implementing the CPEC. Meanwhile, curiously, Pakistan’s Lt General Aamir Riaz called on India to join the CPEC, in December 2016.

What are the various concerns that have found a voice in Chinese public opinion? What do they indicate?

Third Party Dilemma

The CPEC, billed as the flagship project of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has been at the core of Beijing-Islamabad relations since its 2015 launch.

On 21 December 2016, Lt General Aamir Riaz, Corps Commander, Southern Command, Pakistan Army, made a ‘surprising’ statement, calling on India to “shun enmity” and join the CPEC. Lt Gen Riaz invited India to “share the fruits of future development by shelving the anti-Pakistan activities and subversion.” The statement is significant because it comes from the person in charge of security in Balochistan, where, Pakistan alleges, India aids subversive activities to support Baloch separatists.

Beijing’s response to Lt Gen Riaz’s statement was calculated. On 23 December 2016, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying, in her regular press conference, said “I have seen these reports. I wonder whether the Indian side takes this offer made by the Pakistani general as a goodwill gesture….China would like to discuss the possibility of introducing a third party on the basis of consensus with the Pakistani side through consultation.”

Hua’s comments have two aspects that warrant attention: First, it extends support to Pakistan’s offer to India as a “goodwill gesture.” Second, it lays emphasis on reaching consensus through consultation with regard to the inclusion of “third parties.” This indicates that that even China was taken by surprise: her statement shows that China prefers to introduce a third party on the basis of consensus and not unilateral action. It also appears that Lt Gen Riaz’s ‘invitation’ had not been discussed with China.

As expected, media in both countries focused on the ‘support’ aspect. However, one report stood out in its interpretation of Lt Gen Riaz’s statement: an op ed, published on 22 December 2016 in China’s state-run Global Times, titled ‘Pakistan’s CPEC proposal to India sends an important gesture’, written by Liu Zongyi, senior fellow at the Shanghai Institute for International Studies. It appears to tone down the ‘invitation’ by arguing that “the invitation which came as a surprise to New Delhi, was mainly intended as a gesture.” Liu highlights the conditionality laid on India and says that “Pakistanis themselves do not want India to be part of the CPEC, or they believe, if India hopes to join, it must try to improve bilateral ties first. China believes that India should be part of the project and actively persuade Pakistan to accept it.” Liu further argues that “the CPEC runs through Pakistan-controlled Kashmir which is also claimed by India as its territory. It is almost suicidal for Indian politicians to make concessions over the issue. However, this is only an excuse. The fundamental reason why India is against the project is that it fears China could get access to the gate of the Indian Ocean through the corridor and Pakistan’s strength will be enhanced.”

CPEC: Cracks in the Corridor

Key challenges still exist vis-à-vis the CPEC’s implementation in Pakistan.

I

It would be natural to assume that before inviting a bid from a third party – one who is mutually perceived to be a challenger to their rise – China and Pakistan would make efforts to cement the cracks that are appearing in the corridor even before its completion.

As the CPEC enters the implementation phase, voices of concern in Chinese public opinion regarding its feasibility, pace of progress, and security can be observed. On 20 December 2016, the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies of People’s (Renmin) University of China and Caijing Magazine released a ‘Joint Research Report on CPEC’. According to accounts published in the Chinese media, the report, which was compiled after two weeks of field research:

- Concedes that despite successes, the work of building the CPEC has also been plagued with difficulties

- Argues that Chinese investment has become something to be squabbled over among different parties and region-based factions in Pakistan

- States that neither China nor Pakistan can afford a failed CPEC and that if the chaos continues, the flagship project will be delayed, and the CPEC will become China’s burden, with potential for immense negative impact on Beijing’s BRI

- Recommends Chinese companies to seek help from domestic (Chinese) security companies to cope with the security situation in Pakistan.

II

Mao Siwei, China’s former consul-general in Kolkata and a South Asia expert – who had recently ruffled the Chinese establishment’s feathers by arguing in his blog for a course correction by China on the Masood Azhar issue – even crossed the so-called line by questioning the fundamental objectives of implementing the CPEC.

In his blog, titled ‘Three Misgivings on the China Pakistan Economic Corridor’, published on 10 December 2016, Mao discusses what he characterises as China’s three main ‘misgivings’ regarding the CPEC, and argues that:

- The so called “Malacca dilemma” is a false proposition, stating that only the US has the ability to block China’s sea route. He says that in an event of a conflict, if the US chooses to block the Malacca Strait, it would be easier for the US to block Gwadar. In the event of a more serious situation, Chinese tankers can still navigate from a longer route by passing further south of Sumatra.

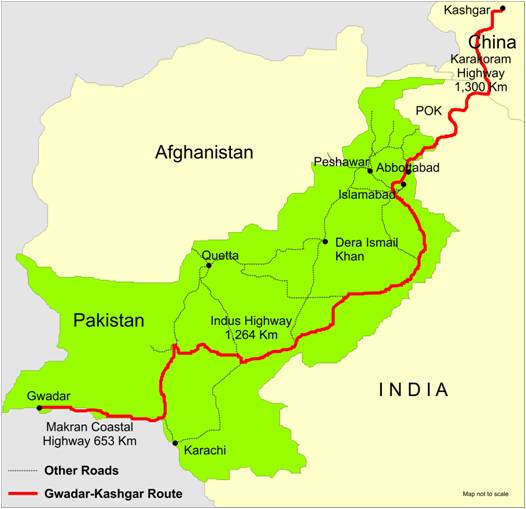

- Regarding access to the Indian Ocean and cross-border connectivity, he points out that although the cargo trial from Kashgar to Gwadar had been completed successfully, the route will take time to become a sustainable business channel. He adds that this route passes through Pakistan’s Balochistan Province, which is currently experiencing severe ethnic separatism, and frequent incidents of religious violence, due to which the security of this route cannot be guaranteed over an extended period of time.

- More importantly, on the issue of Gwadar Port defending China’s legitimate rights in the Indian Ocean, Mao argues that maintaining a certain degree of military presence in the Indian Ocean is necessary, reasonable, and legitimate, but that since the shipping lanes in the Indian Ocean run very close to the Indian coastline, it is essential to maintain friendly relations with India. He argues that if China builds a naval base in Gwadar, it has to come in the form of a treaty or a security alliance, which would indicate that in the event of a conflict between India and Pakistan, China would be bound to stand by Pakistan. However, for decades, Chinese oil tankers and merchant shipping routes in the Indian Ocean have not encountered any security problems, and if China and Pakistan form a military alliance in the Indian Ocean, it will unnecessarily complicate the security of these sea routes.

III

Looking Ahead

China, Pakistan, and the CPEC

Challenges faced by Chinese enterprises engaged in the development of the CPEC in Pakistan are increasing. There are concerns regarding the slow progress on various projects even as Pakistan pushes to pick the “early harvest” (fast-tracked projects on energy and infrastructure). Most projects under the CPEC are commercial in nature, and there are already instances of disputes in contracts and technical specifications. Chinese scholars are increasingly vocal in cautioning Chinese enterprises that the CPEC should not be treated as a political task or be hurried.

CPEC and India

Chinese scholars, including Liu, may be aware that India has repeatedly told China to be “sensitive” to Indian strategic concern that the corridor runs via Gilgit-Baltistan, which is originally a part of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. What they often fail to highlight is the flaw in making India’s entry into the CPEC conditional. It is illogical to ask India for a compromise that would make it eligible to join a corridor that New Delhi is not even keen on. India is unlikely to consider the proposition to join the CPEC unless its interests are addressed, which remains unlikely at the moment.

Moreover, would Islamabad and Beijing be ready to accommodate India’s participation in this corridor, which connects Xinjiang and Balochistan, two restive regions in China and Pakistan, respectively? Even if the ‘invitation’ was a “goodwill gesture,” as Hua termed it, it remains to be seen how accommodating China and Pakistan would be vis-à-vis India becoming a stakeholder in infrastructure projects along the corridor.

Or, was Lt Gen Riaz’s invitation only a wild attempt to gain legitimacy by linking a few roads from western India to Lahore?

Courtesy: http://www.ipcs.org/article/india/cpec-third-party-dilemma-and-cracks-in-the-corridor-5229.html