A constabulary role and coordination between the civil agencies lie wholly outside the scope and capability of the Indian Navy. The IN should not even consider venturing into those domains as it is already overstretched by the enhanced expectations from the developing scenario in the Indian Ocean Region and the South China Sea. Dealing with sea piracy is yet another pressing issue. The inability of the entire international maritime community to suppress the piracy menace originating from Somalia in spite of all its resources is a pointer to the dilemma.

After the serial blasts in Mumbai in 1993, post 26/11 attacks in Mumbai and the incidents of beaching of MVs Wisdom and Pavit on Juhu beach as well as the sinking of MV Rak off the coast of Mumbai – there was public outrage after each of the major tragic incidents.

On each occasion, public perception pointed a finger at the Indian Navy (IN). Notwithstanding the clear jurisdictional demarcation of responsibilities, the media also held the Navy guilty of dereliction of duty. Conveniently, the government also did not make any attempt to correct this flare-impression.

As an attempt is made to take stock of the coastal security architecture for a reality check, the vastness of the domain involved must be appreciated. Seeking a rogue ship or craft in the middle of an ocean is nothing less than looking for a needle in a hay stack. To keep abreast of the situation in a defined area of interest in, say Iraq or Afghanistan, the US had to deploy an array of surveillance satellites. Even then, 24×7 coverage was an impossible task. In addition, Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) aircraft, carrier-based surveillance aircraft and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) were also extensively used along with Special Forces (SF) troops on the ground.

The vast Indian coastline of over 7,500 kilometres is spread along nine coastal states and four union territories. Security at the twelve major ports and almost two hundred minor ports in the country is of concern. The conventional security of the major ports is the responsibility of the Central Industrial Security Force (CISF), the minor ports being the responsibility of the State Maritime Board/State Government. Additionally, the twelve major ports, fifty three minor ports and five shipyards conform to the International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPFS) requirements.

The traditional peacetime jurisdictional responsibility between the IN and the Indian Coast Guard (ICG) was simple. The ICG is responsible for the security of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ); beyond that, extends the security responsibility of the Navy. The port authorities, the DG Light House (DGLH), customs, police, immigration, Intelligence Bureau and narcotics control agencies had their respective roles cut out for them along the coast, ports and harbour regions. Demarcation of responsibility in respect of the sea front security of coastal, industrial, military, DAE and off-shore establishments, was also clearly stipulated.

The truth of the matter is that none of the above incidents need have happened, had the institutions, designated for each task and zones, been geared up, alert and net-worked. The serious lacuna that existed at the time of 26/11 would be clear from the fact that since then over approvals with Rs 2,000 crore have been accorded by the Cabinet Committee on National Security for capital expenditure towards creating/upgrading infrastructure dedicated for coastal security. The systemic inter-departmental coordination inadequacies were crippling. These would take over a decade to overcome, provided the establishment has the will and determination to evolve and implement an out-of-the-box solution.

Many agencies including the Central Government Ministries/Departments, the respective State Governments and linked local administrative/law enforcement/intelligence agencies are deeply involved in affairs of coastal security. The Navy should focus on its primary role and only be expected to provide overall guidance and maritime expertise in creating the necessary infrastructure, including coastal Command, Control, Communication, Intelligence and Surveillance (C3IS) network and provide training skills in preparing the personnel concerned for working in a maritime environment. Also, the coastal information network should be closely integrated into the networks of the IN and ICG’s C4ISR – so that an integrated scenario is always available. To the extent of maintaining a network capable of receiving inputs from the multifarious sensors/sources. Facilitating access to such information on real time basis to the concerned agencies is a responsibility the Navy could take on.

A constabulary role and coordination between the civil agencies lie wholly outside the scope and capability of the IN. The IN should not even consider venturing into those domains as it is already overstretched by the enhanced expectations from the developing scenario in the Indian Ocean Region and the South China Sea. Dealing with sea piracy is yet another pressing issue. The inability of the entire international maritime community to suppress the piracy menace originating from Somalia in spite of all its resources, is a pointer to the dilemma. Having said that, an overview of the measures taken by the government since the Mumbai serial blasts in 1993, on coastal security is discussed briefly in the succeeding paragraphs.

Following the serial blasts in Mumbai, Operation Swan was launched with the limited objective of preventing the landing of contraband and infiltration along the Maharashtra–Gujarat coast. Among other measures, the Government authorised the ICG an expenditure of over Rs 340 crore for acquisition of fifteen fast interceptor boats and setting up of three ICG Stations at Dhanu, Murad Janjune and Verawal. In 2000, the issue of coastal security was once again highlighted by the Task Force on Border Management as a part of the Kargil Review Committee recommendations. The recommendations included:

Following the serial blasts in Mumbai, Operation Swan was launched with the limited objective of preventing the landing of contraband and infiltration along the Maharashtra–Gujarat coast. Among other measures, the Government authorised the ICG an expenditure of over Rs 340 crore for acquisition of fifteen fast interceptor boats and setting up of three ICG Stations at Dhanu, Murad Janjune and Verawal. In 2000, the issue of coastal security was once again highlighted by the Task Force on Border Management as a part of the Kargil Review Committee recommendations. The recommendations included:

- Setting up of a specialised marine police force in the form of coastal police stations

- Augmentation of the strength of the ICG

- Formation of fishermen watch groups

- Establishment of an apex body for the management of maritime affairs.

An apex body, the National Committee on Strengthening Maritime and Coastal Security (NCSMCS) against threats from the sea was constituted. The body is chaired by the Cabinet Secretary and its members are all stakeholders such as the Indian Navy, the Indian Coast Guard, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA)/Fisheries/Shipping/Surface Transport/Agriculture, DG Light House/Ships and Chief Secretaries of Coastal States. The first meeting was held on September 04, 2009.The NCSMCS, unlike many other such bodies, meets quite regularly.

An apex body, the National Committee on Strengthening Maritime and Coastal Security (NCSMCS) against threats from the sea was constituted. The body is chaired by the Cabinet Secretary and its members are all stakeholders such as the Indian Navy, the Indian Coast Guard, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA)/Fisheries/Shipping/Surface Transport/Agriculture, DG Light House/Ships and Chief Secretaries of Coastal States. The first meeting was held on September 04, 2009.The NCSMCS, unlike many other such bodies, meets quite regularly.

The present status of the assets of the ICG could be summarised as below:

- Platform holdings – ninety-three surface craft and forty-six aircraft.

- Future plans include two hundred ships/small craft and ninety aircraft.

- Thirty per cent increase in manpower has already been approved.

- By the end of present Eleventh Plan period the ICG will have forty-two ICG Stations.

- Four Regional/ Joint Operations Centres (ROC) have been set-up and networked to customs & IB at Mumbai, Vizag, Kochi and Port Blair.

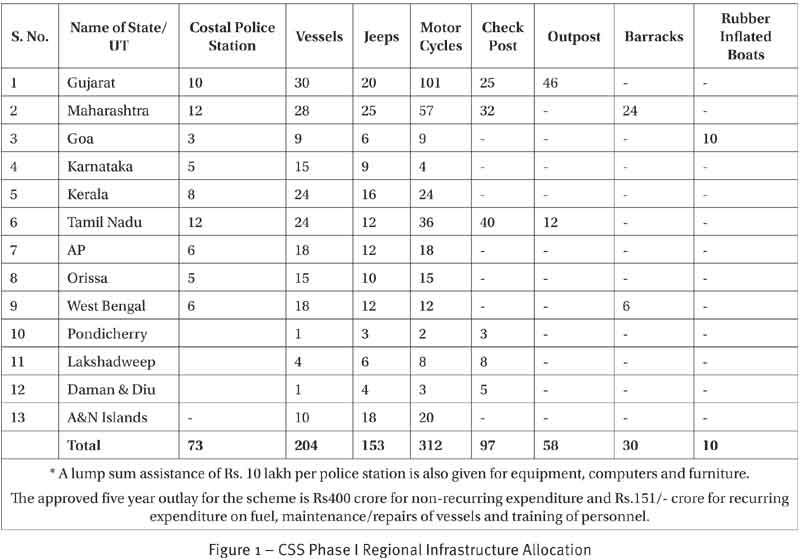

In 2005, the Coastal Security Scheme 2005 (CSS2005) was sanctioned by the CCS. CSS2005 introduced the concept of a three-layered coastal patrol system between the IN, the ICG and the Coastal Police. The CSS2005 provided for a comprehensive five-year plan with an allocation of Rs 400 crore for non-recurring and Rs 150 crore as annual recurring expenditure for Phase I.

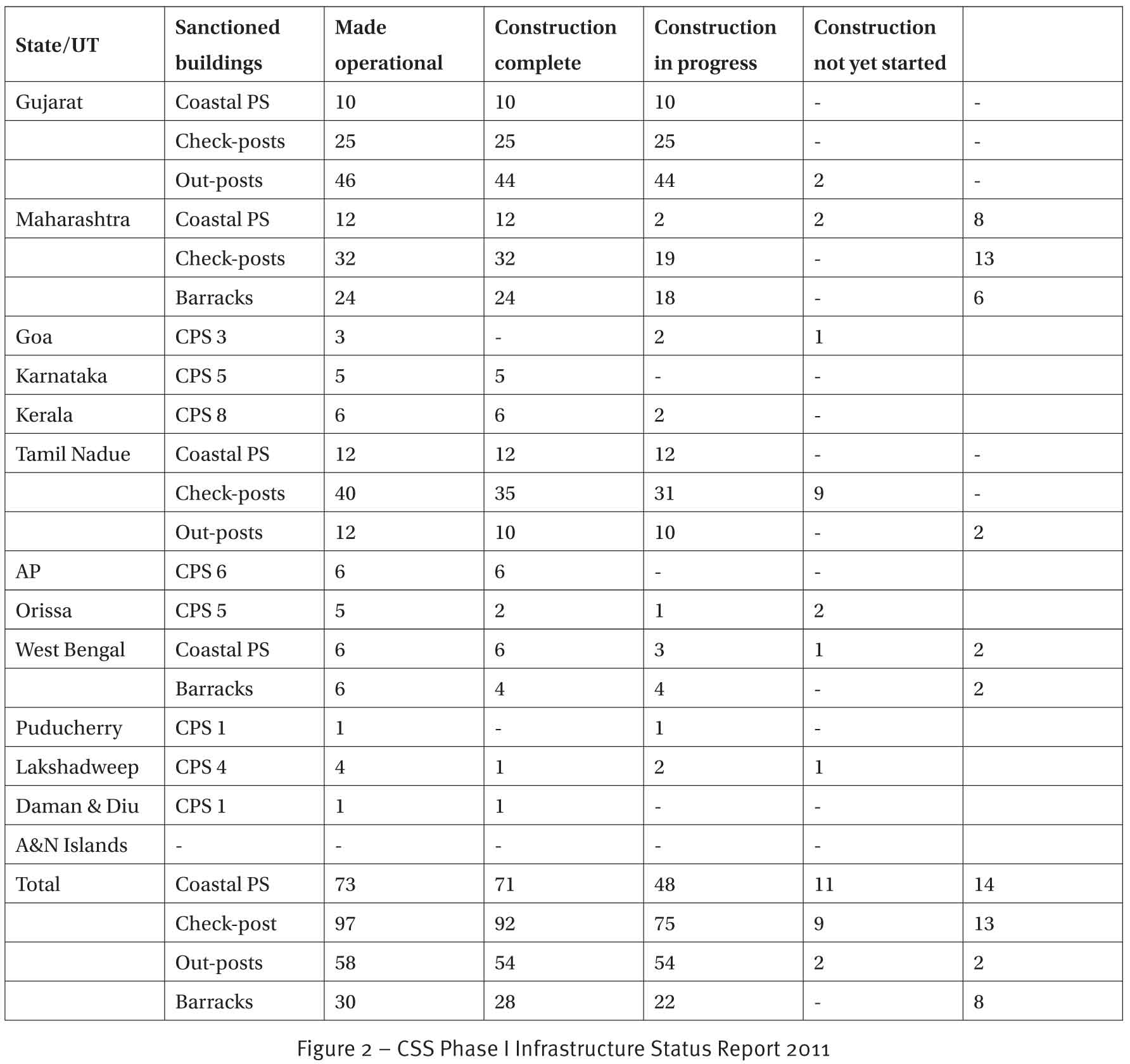

The breakdown of the type of infrastructure sanctioned against CSS Phase I is listed at Figure 1. The status of the infrastructure sanctioned, as of early 2011, is indicated at Figure 2. The MHA report for 2010–2011, accordingly claims that on all India basis – over 92 per cent of the 73 Coastal Police Stations (CPS) sanctioned for the Phase I had been made operational by January 2011. In Maharashtra, it also indicates that, of the twelve CPS sanctioned no construction work had commenced on eight of them.

In mid-2011, when several incidents of ships drifting on to Mumbai beach took place, media reports indicated that the CPSs in Mumbai were no where near ready. There were reports of boats tied up alongside, unable to undertake any patrolling due to lack of fuel supply and inadequate technical manpower. In spite of all the public outrage at the time of the series of episodes, when considered along with the MHA report above, it clearly illustrates the apathy displayed by the state authorities.

The present demarcation of zonal responsibility is as follows:

- Marine Police : up to 12 Nautical miles

- Indian Coast Guard : from 12 to 200 NM

- Indian Navy : beyond 200 NM

Activities in respect of the following are also well underway:

- Arrangement for issue of ID Cards / Universal Identity Cards (UID)

- Introduction of Automatic Identification System (AIS), Electronic Tracking Device (ETD) and compulsory registration of vessels

- Eighty-four AIS stations have been contracted for in September 2011 at a cost of Rs 132 crore

- Fitment of AIS on fishing vessels above twenty metres in length has already been made compulsory

- Distribution and status of Sensor Stations in Phase I are as follows:

- The ICG in high threat areas has forty-six electro–optical sensor Stations

- Twelve Remote Operation Sensors/Station (ROS) are fed into one of four Regional Operations Centres (ROC) at Mumbai, Kochi, Chennai and Vishakhapatnam.

- All will be fed, on real time basis, to the Apex Control Centre at Gurgaon, NC3I complex and inter-linked to the Navy’s Combat Management Centre.

- The BEL Project cost for developing software for CSS is estimated to be about Rs 700 crore.

- The ROS will have the means to remotely manipulate coastal radars and cameras through a Camera Management System. Integral health monitoring and alarm system has also been catered for.

- Infra-red (IR) cameras are being procured from Israel; daylight cameras from Canada and coastal surveillance radars from Denmark.

- The DG Light House has, at a cost of 12.2 million Euros, contracted with SAAB for an integrated coastal surveillance system. The system comprises seventy-four sensor stations linked to six Regional Control (RCC) Centres and three National Control Centres (NCC) which are to be connected through broadband satellite links.

- Coastal Radar chain plan comprises forty-six Coastal Radars. This was contracted in September 2011 for Rs 601.77 crore with BEL. Deliveries are planned to materialise within the year. It is reported that the existing Light Houses with the DGLH will be responsible for operations/maintenance of the Radar and Electro Optics Sensors. Thirteen towers will be set up ashore in Phase I and thirty seven more in Phase II.

The Concept of Maritime Domain Awareness

In April 2010, the NCSMCS approved the concept of National Maritime Domain Awareness (NMDA) for an integrated information grid for sea-farers. Basically, this revolves around Navy’s National Command, Control, Communication & Intelligence (NC3IN) system at the centre of the hub. This will generate a ‘Common Operational Picture’ (COP) through an institutionalised mechanism of collection, fusing and analysing information, involving:

- Coastal surveillance network by radar

- Space-based automatic identification system

- Vessel Traffic Management System (VTSM)

- Registration of fishing vessels

- Creation of a biometric identity database for fishermen.

The concept of MDA is not new to the Navy. In its traditional domain, whether in the strategic, operational or tactical roles, the Navy has been in this business all along. This is part of its SOP in all four domains – sea, sub-sea, air and cyberspace. Since 26/11, this concept is now required to be carried forward to the National level and stretched to include coastal security and strategic maritime concerns, in a holistic manner.

The MDA is only one element of the coastal security architecture which receives, collates, analyses and makes the information accessible to all stakeholders for action. To that extent, the Navy as a facilitator can be nominated as the situational head in the form of the Nodal Agency. Each domain stakeholder must be held responsible for converting this domain awareness capability empowerment into pre-emptive/proactive/reactive actions.

The MDA architecture must provide for networked inputs from and outputs to all stakeholders including the National Intelligence Agencies, on real time basis. The Regional and National Maritime Operations Centres must be manned by professionals with domain knowledge and the capability to sift out actionable information from raw intelligence inputs from multifarious technical and human sources and create a realistic comprehensive Common Operational Picture. To assist in handling this task speedily and efficiently, computerised data integration and automated algorithms to assist in handling such vast and disparate data stream would be essential. Embedding of an intelligence agency element here on reciprocal basis, would enrich and enhance the effectiveness of the system

It would be seen from the MHA’s reports that in terms of hardware, considerable stress has been laid on putting in place technological wherewithal to meet the requirements of surveillance. The HUMINT capability with respective stakeholders is at present very weak. Sufficient attention has not been paid in evolving an overall C2 mechanism down to grassroots level. Having an apex-body at the national level is not sufficient. C2 structure at all levels must be formulated, promulgated and implemented. Situational Heads for each domain must be identified and notified so that accountability is not in doubt.

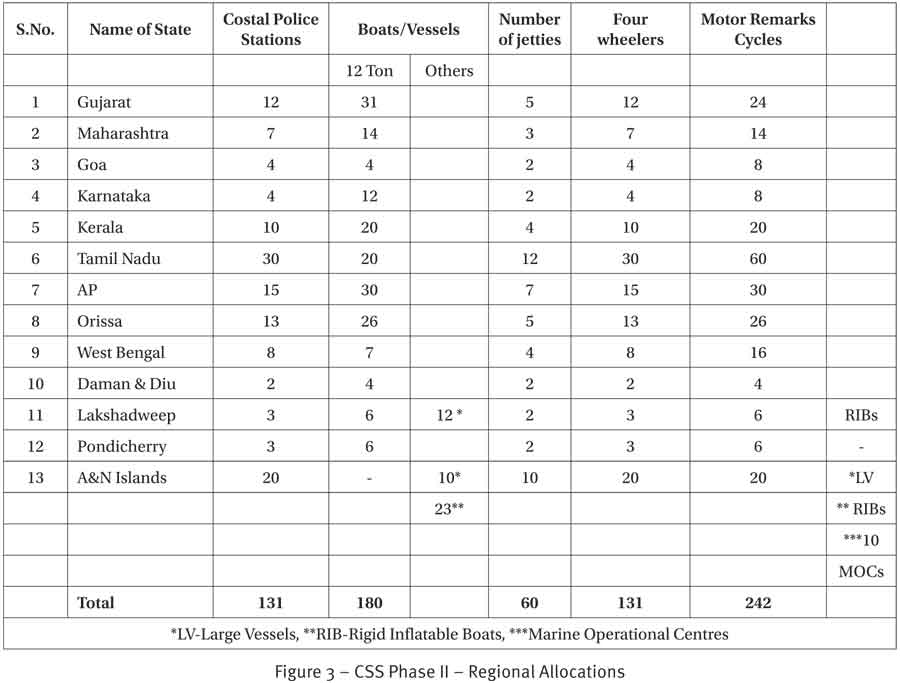

In Sept 2010, the Cabinet Committee on National Security approved the CSS Phase II with an outlay of Rs 1,100 crore for the five years (2011–2015). The CSS Phase II regional allocation is tabulated in Figure 3.

The Navy has also been authorised a thousand strong dedicated specialised force, called the Sagar Prahari Bal, whose role is to provide security protection to all naval assets and bases on the East and West coasts and the island territories.

The Navy has also been authorised a thousand strong dedicated specialised force, called the Sagar Prahari Bal, whose role is to provide security protection to all naval assets and bases on the East and West coasts and the island territories.

The proposal of creating a National Maritime Advisory Board with a Maritime Adviser is presently on hold and the Navy seems to have reconciled itself to the idea that the NCSMCS with the CNS as a member adequately meets the need. However, the issue of lack of coordination between various agencies involved in coastal security still persists and most of the governments in the coastal states continue to remain indifferent to coastal security.

The Coastal Police Force

The main issue remains unresolved. No amount of technical surveillance hardware can compensate for the lack of human intelligence capability and efficient intelligence coordination, investigation and constabulary capabilities. A dedicated coastal agency that will be responsible for intelligence coordination, analysis and empowered to act is essential. They need to work closely with the respective state civil administration.

The recruitment policy for the Coastal Police Force (CPF) needs to be reviewed. The scheme of inducting volunteers from the local police has not worked out. Since there are only few volunteers most of the undesirables have been palmed off to CPF. Most are land lubbers, prone to sea sickness and disgruntled. It appears that the grant of an incentive of fifty per cent of the basic pay as additional allowance is inadequate. Unless there are enough motivated, dedicated and capable boots on the ground as beat constables both ashore and afloat, this scheme is unlikely to work out.

The Maritime Police Force needs to be an elite force – hand-picked, with specific expertise for each category of personnel. They must be duly trained and well compensated to attract the best human resources. Those on the beat and in the police stations must not only be competent but also sensitised enough in order to have the confidence of the local population. Those manning the patrol vessels should be drawn from the local sea-faring population and retired naval personnel.

As discussed earlier, the National Coastal Security System is a complex, multi-agency organisational set up which is still in its infancy. The CSS structure is based on a hub-and-spoke principle. The set-up has five basic levels and each spoke works in its own stovepipe. The CPF and the Coastal Force Police Stations (CFPS) are at the first echelon in one of the stovepipes. The raw information/intelligence and data collected at the grassroots, both from the HUMINT and TECHINT sources are transmitted to the Area Coastal Security Operation Centres (ACSOC) at the second echelon level. After sifting through the inputs from all sources, the relevant ones are forwarded to the State Coastal Security Operations Centres (SCSOC). The SCSOCs are collocated at CG District HQs. This is the third echelon. The next level is at the Regional Operations Centres (ROC), which are collocated at the CGROCs. The next echelon is at the four Joint Operations Centres (JOC) at Mumbai, Visakhapatnam, Kochi and Port Blair. This provides an integrated picture at all the Naval Commands. Finally, a Combined Operational Picture (COP) is generated at the national level at the National Maritime Operations Centre (NMOC).

The DGLH, Customs and IB operate independently in their respective stovepipes and feed the inputs generated within their domain, in a similar manner, to the ROC and then on to the respective JOC and finally, to the NMOC to create an overall Maritime Domain Awareness picture.

Action within the domain of each entity is to be taken at the respective zonal level. The ICG’s assistance can be sought at the discretion of CFPS to deal with any situation outside its capacity. Similarly, when called upon, the Commander-in-Chiefs of the respective Naval Commands would provide assistance to the ICG. The onus of responsibility for action in the respective zones would squarely rest with the designated zonal agency.

Unfortunately, the system being created in the twenty-first century is still geared to work in stovepipes. Each sub-set is working independently and is only responsible to its own hierarchy. There is no structured single entity in place that is responsible and has the authority to oversee the functioning of all the stovepipes at each level in the entire system.

The system logic is that each agency in the stovepipe is expected to effectively fulfil its respective designated role. That is considered sufficient, for appropriate action to be taken by the Operations Centres at the hub. Periodic coordination meetings between the stakeholders and regular structured exercises are considered adequate to ensure performance.

Each of the agencies identified here is venturing into unchartered waters where they have little or no experience or expertise. The Navy, the ICG and the Original Equipment Manufacturers responsible for providing the sensors and the integrated network systems are being called upon to train their personnel. It seems that the Indian ethos does not permit the concept of situational heads (with overall domain expertise) being given authority and responsibility over the whole network.

| Editor’s Pick |

In the circumstances, designating the Navy as a nodal agency and DGCG as the Commander of the Coastal Command seems a futile exercise. Firstly, there is no such entity as a Coastal Command. Also, in this context the questions that beg answers to are:

- What is expected of the IN as a nodal Agency?

- Is the Navy expected to play the role of a whistle-blower?

- If so, does that entail bearing sole responsibility for providing actionable information to all the CSS Operations Centres?

- With the Navy having little or no say over how, when and what type of information each agency has to focus on, is that a realistic expectation, particularly in the present dynamic situation?

- Is it restricted to the management of the integrated MDA communication network only?

- As a service provider to the stakeholders in the CSS, is the Navy just a recipient or a custodian of the inputs received from the designated sources, with the responsibility as a facilitator to the subscribers, to make the means of access available to them, on demand – on line, on real time basis?

- Is the Navy expected to be responsible for the entire CS system?

If results are to be expected from this initiative, it would be more appropriate to give the DGCG additional charge of the over all coastal security arrangement and formally designate him as the situational head for the entire coastal security system, duly empowered. In that capacity and as the Commander Coastal Command, he must be given full operational charge of all the stovepipes. The technical and administrative control can be retained by the respective departments. In the dynamic situation of today, for prompt action, an institutional mechanism must be put in place permitting oversight, coordination and operational control with one authority.

On the question of mind-set block and turf considerations coming in the way of progressive reforms, one needs to take a good look at the post-9/11 scenario in the USA, especially at the salutary changes brought about in the US intelligence structure. Suffice it to draw attention here to the way CIA has accepted the idea of embedding its operatives under the Special Forces with the US Central Command in Iraq and Afghanistan, and how the entire US Intelligence setup has been revamped to:

- Amalgamate all analytical talents residing in CIA, FBI, and DIA into a conglomerate and

- Emulate the military in separating the organisation, training and equipping function from operational deployment functions.

Notes

- “National intel grid to thwart maritime threat from Jan?” TOI 06 Dec 2010.

- http://www/icc.org/piracy-reporting-centre/request-piracy-report - International Chamber of Commerce – International Maritime Bureau - “Piracy & Armed robbery against ships”.

- http://ajaishukla.blogspot.com/search?q=coastal.

- http://www.sanctuaryasia.com/resources/environlaw/crz.doc.

- Maritime Domain Awareness www.globalsecurity.org/intell/system/mda-htm.

- PK Gosh “Coastal Security arrangement in Maharashtra: An Assessment. IDSA.

- PK Gosh “India’s Coastal Security – Challenges and Policy Recommendations” www.orfonline.org.

- Ranjit Pandit “3yrs after 26/11. Govt OKs coastal radar chain” TOI 12 Sept 2011.

- www.brahmand.com/news/india-to-set-up-National-MDA-grid-for-coastal-security/5687/3/13html.

- www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/x.

- www.idsa.in/idsacomments/WitherCoastalSecurity_pdas_261109.

- www.marinebuzz.com/2010/03/31/india-coastal-security-scheme-update.

- www.mha.nic.in/pdfs/AR(E)1011.pdf./ Annual report MHA 2010-2011.

- www.observerindia.com/cms/or/online/modules/issuebrief/attachment/Ib_22_1283150948708.pdf.

- www.security-risk.com/security-trends-south-asia/india-defence/india’s-coastal-secirity-profile-the officialview.