Akhaura

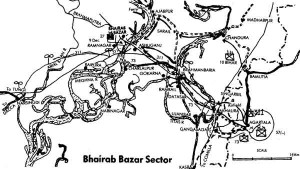

Pakistan’s 27 Brigade held the Akhaura-Brahmanbaria area. Akhaura, just across the border from Agartala, was an important rail-junction. For that reason the Pakistanis had paid considerable attention to its defences. These were mainly based on the Titas River, which ran West of the town, and some bils in the area. Six kilometres South of Akhaura was Gangasagar (see Fig. 13.6). The defences at the two places were manned by about one battalion strength of regular infantry, a good number of paramilitary personnel, a few PT-76 tanks and some artillery. The Agartala airfield was close to the border and had been under fire.

To ensure its security, defensive action was ordered by General Sagat Singh towards the end of November. Brigadier Tuli was to neutralize Gangasagar while Misra was to tackle Akhaura.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

It was during the battle for Gangasagar that the only PVR awarded during the Bangladesh campaign, was won by Lance Naik Albert Ekka of 14 Guards. As part of the operation by 73 Brigade, this battalion put in a silent attack on the first objective, the town’s railway station, in the early hours of 3 December. The enemy was well entrenched in concrete bunkers. While assaulting one of these, Albert Ekka was wounded but succeeded in capturing a light machine gun and bayoneting two of the enemy. After the battalion had cleared most of the enemy from the railway station area, a medium machine gun in the second storey of a building held up further advance.

According to Pakistani sources, the Indian move towards Ashuganj was no surprise to them and they expected it.

Ekka again displayed outstanding courage; he crawled up to the building and threw a grenade through a loophole, killing one of the enemy. Then, with complete disregard for personal safety, he climbed a side-wall, entered the top bunker and bayoneted the machine-gun crew. This led to a quick fall of the position. The battalion captured a large quantity of arms and six prisoners. Their own casualties were 10 killed and 53 wounded, including one officer and three JCOs.

Akhaura proved a tougher nut to crack. The battalions under Brigadier Misra struggled against its defences for three days before they were finally reduced on the morning of 5 December, 18 Rajput providing the coup de grâce. One of the battalions, 4 Guards, managed to infiltrate West of the Titas and discover that the double-track railway running to Brahmanbaria had been converted into a rail-cum-road track by removing the rails from one of the tracks. It was also found that the bridge over the Titas was almost intact and lightly held. These discoveries led to a change in the division’s task. Instead of going South it was now ordered to advance North-West to Ashuganj by way of Brahmanbaria. The change was to lead to a rapid strike by 4 Corps across the Meghna.

After the battalion had cleared most of the enemy from the railway station area, a medium machine gun in the second storey of a building held up further advance.

On 5 December the forward elements of 311 Brigade began to advance towards Brahmanbaria. The next day 73 Brigade also commenced its advance. A Mukti Bahini force had been operating under Gonsalves in the Akhaura area, That day he ordered this force, together with 10 Bihar, to make an outflanking move by way of Chandura and Sarail to the Ajabpur ferry on the Meghna. Brahmanbaria was about 14 kilometres North-West of Akhaura and lay in a loop of the Titas. This situation gave it a good defensive potential and the Pakistanis had developed it into a strongpoint. After the fall of Akhaura its garrison had withdrawn there.

According to Pakistani sources, the Indian move towards Ashuganj was no surprise to them and they expected it. However, while they waited for a frontal assault on Brahmanbaria, 73 Brigade pushed out two prongs: one to the town’s South and another to its West. Reacting to this manoeuvre they abandoned the town on the night of 7/8 December, and made for Ashuganj, 13 kilometres to the North-West.

On the morning of 8 December, Gonsalves ordered 311 Brigade to take up the pursuit; he wanted to capture the bridge at Ashuganj before the enemy had settled down. However, the build-up of his division at Brahmanbaria had not been quick enough. Besides, the enemy had damaged the bridge there. Even the bridge West of Akhaura was not yet fit for heavy vehicles and it was not possible to bring forward bridging equipment. This meant that 311 Brigade would have no artillery support in its advance to Ashuganj. The easy fall of Brahmanbaria had, however, given the impression that the enemy was disorganized; hence the decision to risk a pursuit without artillery. The PT – 76 tanks were expected to give enough support.

The Pakistanis, however, had had the time to sort themselves out. They were well-dug in at Ashuganj by the time the leading elements of 311 Brigade (18 Rajput) got there on 9 December. The brigade had not met any serious opposition after Brahmanbaria and did not expect any at Ashuganj. As at Kushtia, the Pakistanis let the Indians come into the built-up areas and then opened up. The brigade lost 120 men and 4 tanks.18 About this time 10 Bihar also arrived from the North and both battalions had to fall back.At this stage the Pakistani divisional commander ordered the blowing-up of the Ashuganj bridge. This left his 27 Brigade on the East bank of the Meghna but it managed to cross over and reach Bhairab Bazar.

By this time the river-ports of Daudkandi and Chandpur had been abandoned by the enemy as a result of the operations of 23 Division. Between Ashuganj and Dacca the enemy had only the Razakars and the EPCAF. They had no artillery support and Dacca itself had only one regular battalion of infantry, which was holding the home-bank of the Lakhya River. Accordingly, Sagat Singh decided to cross the Meghna straightaway, using the helicopters placed at his disposal. A landing zone was chosen near Raipura, about 15 kilometres South-West of Bhairab Bazar. Thence, the two brigades under Gonsalves were to move along the rail-track to Narsingdi, which was to be developed as an advanced base for the attack on Dacca. The heliborne crossing was to be supplemented by ferrying troops and equipment, using local resources.

| Editor’s Pick |

Brahmanbaria was the base for the heli-lift which began during the afternoon of 9 December; it continued during the night till the moon set. On the following day troops were flown direct to Narsingdi while 311 Brigade was mostly lifted by air, 73 Brigade used river-craft for the crossing. The Pakistanis at Bhairab Bazar were kept in check by the deployment of two infantry battalions South of the town and by aerial action.

The build-up at Narsingdi was however, slow as only about ten helicopters were available. Ferrying of artillery and tanks across the Meghna also posed serious difficulties. However, by 14 December both brigades had crossed it and the first artillery shell was fired on Dacca that day. The ground attack could begin only two days later and the cease-fire intervened before the operation could develop.

Comilla

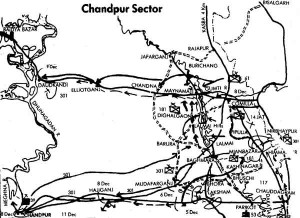

Pakistan’s 39 (ad hoc) Division, under Major General Mohammad Rahim Khan, was deployed in the Comilla-Laksham-Chandpur-Daudkandi area. (see Fig. 13.7). Its 117 Brigade was holding the border from the North of Comilla to Chauddagram, while its 53 Brigade was responsible for the area further South up to Feni. Major General Hira’s operations in the Belonia bulge had led the Pakistanis to believe that 4 Corps’ thrust was likely to be towards Feni and Chittagong. However, they had not neglected the defences of Laksham and Comilla, which stood on the route to Dacca. Between Comilla, the main city in the region, and Laksham, was a string of hillocks called the Lalmai Hills.

“¦they had not neglected the defences of Laksham and Comilla, which stood on the route to Dacca. Between Comilla, the main city in the region, and Laksham, was a string of hillocks called the Lalmai Hills.

They dominated Laksham and the Pakistanis had fortified them. On the Northern tip of the Lalmai Hills stood the cantonment of Maynamati. Both Laksham and Maynamati had been turned into fortresses and it would have been costly to reduce them and then advance to Chandpur, the main objective of 23 Division. Infiltration between the Lalmai Hills and Laksham was therefore decided upon.

The force selected for this task was 301 Mountain Brigade under Brigadier Harinder Singh Sodhi which had a squadron of PT-76 tanks under command. Simultaneously, 83 Mountain Brigade; commanded by Brigadier B.S. Sandhu, was to isolate Laksham from the South, while 181 Mountain Brigade under Brigadier Y.C. Bakshi, was to follow 301 Brigade and cut off Laksham from the North and West. While these moves were afoot, 61 Brigade led by Brigadier pande, was to keep the Pakistanis at Maynamati occupied and also make a bid for Daudkandi.

Led by 14 Jat, 301 Brigade began to move in soon after dusk on 3 December. The brigade made good progress. In fact, during this initial operation it received the first large surrender of the campaign. Two companies of 25 Frontier Force were holding the Mian Bazar area, South of Comilla. After Sodhi had cleared Mian Bazar on 4 December, they began to pull back to their layback positions further West. To their dismay they discovered that 1/11 Gorkha Rifles had already occupied them. Trapped, they were forced to surrender. The bag included the battalion commander, five of his officers, eight JCOs and 202 other ranks.

By first light on 5 December, 181 Brigade had cut the road and railway-line between Laksham and Lalmai and blocked Laksham from the West. This helped Sodhi and in a surprise move, he took Mudafarganj the next day, with the bridge over the Dakatia intact. His 1/11 Gorkhas had infiltrated during the previous night, moving manpack, each person carrying between 30 and 35 kilograms of equipment.The enemy was sensitive about Mudafarganj. About ten kilometres North-West of Laksham, the town lay on the main route to Chandpur. General Khan decided to recapture it. He had come to know of the loss accidentally. On the afternoon of 6 December he was on his way from Chandpur to personally organize the defence of Laksham. When his party neared Mudafarganj it came under fire; the Gorkhas seized the pilot jeep, though his own vehicle managed to turn and escape.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

By this time the enemy 53 Brigade had withdrawn to Laksham after a mauling by Sandhu’s 83 Brigade. Two Pakistani columns set out from Laksham on 7 December to retake Mudafarganj. Each had two to three companies of infantry under a lieutenant colonel who were to attack their objective from different directions. Around 2300 hours that night one of the columns (15 Baluch) reached Mudafarganj. By then only two companies of 1/11 Gorkha Rifles were left there, as Sodhi had set out for Hajiganj during the evening with their remaining companies and 3 Kumaon.

The enemy was sensitive about Mudafarganj. About ten kilometres North-West of Laksham, the town lay on the main route to Chandpur.

The Gorkhas at Mudafarganj had no mines or wire for their defences but they battled with the Pakistanis for four hours and succeeded in repelling them. The second column (two companies of 23 Punjab [Pakistan] and one company of Azad Kashmir troops) failed to show up—it had got embroiled with the Mukti Bahini on the way.

After the action at Mudafarganj the Baluch companies were called back to Laksham while the second column was ordered to Hajiganj. The two colonels were now with that column and they decided to move cross-country and hit Hajiganj from a flank, not realizing that 301 Brigade would get there earlier, moving by road. Sodhi entered Hajiganj on 8 December, his troop getting a rousing welcome from its people. The town had been taken during the morning by 3 Kumaon after a brisk action. The Pakistani column reached the town that night and was dispersed easily. Chandpur was also evacuated that night.

Meanwhile 14 Jat had taken Comilla. Responding to the pressure against Maynamati, the Pakistanis had mostly cleared out of the city, except for paramilitary personnel. The Jats happened to be in the Majlispur area, South-East of the Lalmai Hills on the morning of 7 December and General Hira ordered them to go and capture Comilla. They marched 30 kilometres to launch the attack. Begun at last light the operation was over by dawn on 8 December.A column of 61 Brigade, led initially by 2 Jat and later by 12 Kumaon, had been launched towards Daudkandi on 6 December. It had a troop of tanks in support but hardly any transport. Mules, porters and rickshaws were pressed into service and the column was able to take Chandna, 17 kilometres West of Comilla, the next day. After a sharp action at Elliotganj, the leading elements reached Daudkandi on the evening of 9 December. While this operation was under way, the rest of the brigade kept Maynamati engaged.

Most of them were keen to give themselves up, but not to the Mukti Bahini as they were very scared of it.

The Lalmai defences were seized on 8 December by a battalion of 181 Brigade. By then Laksham had been surrounded and was subjected to heavy-duty doses of shelling and air-strikes. The garrison became nervous and reacted to Indian jitter parties as if they were major attacks, firing wildly and wasting ammunition. On 9 December a rumour was set afloat that a full-scale attack on Laksham would be launched that night. At the same time the civil population of the villages to the North of the town was told to clear out. This touched off an exodus. The garrison split into columns and made for Maynamati during the night, taking only their personal arms along. A portion managed to reach their destination, but a large column, more than a thousand-strong, was rounded up three days later after it had tried to fight its way to Maynamati.

This cantonment now had two Pakistani brigadiers and a garrison numbering about 4,000, with a battery of guns and four tanks. After an attack by 7 Rajputana Rifles (61 Brigade) had established a foothold on the defences, 61 and 181 Brigades were ordered to capture the cantonment. However, Maynamati defied capture till the general surrender of 16 December.

When the first group jumped into the water, they found it six feet deep. The group happened to be Gorkhas and two of them were drowned. The operation was thereafter halted.

After reaching Chandpur, 301 Brigade was busy rounding up Pakistani stragglers. About 700 were brought in. They were bedraggled, hungry and badly shaken. Most of them were keen to give themselves up, but not to the Mukti Bahini as they were very scared of it. A party of 60, under a subedar-major, surrendered to two unarmed jawans who had gone to the riverside for a stroll. The party had been in hiding, waiting for an opportunity to surrender. There were some encounters with Pakistanis attempting to flee towards Dacca in launches and steamers. Many of these attempts were foiled.

On 11 December, Brigadier Sodhi was told that his brigade should move to Daudkandi, cross the Meghna, secure Baidya Bazar and then cross the Lakhya River South-East of Dacca. Chandpur was not linked to Daudkandi by road. 301 Brigade had, therefore, to go back the way it had come and take the Comilla-Daudkandi road. It was ferried across the Meghna partly by river-craft and partly by helicopters. The advance to the Lakhya on 15 December was virtually unopposed. However, the enemy was present in some strength in the built-up area opposite Narayanganj and 14 Jat suffered heavy casualties in clearing it. By the time Sodhi heard the news of the surrender, 1/11 Gorkha Rifles had crossed the Lakhya. Two brigades of 57 Division were also poised for an attack on Dacca from the North-East at this time.

After the fall of Laksham, 83 Brigade was ordered to join Kilo force, then advancing on Chittagong. The terrain was difficult and opposition quite stiff. The combined force was still fighting near Sitakund when Dacca fell.

A seaborne landing was launched against Cox’s Bazar on 12 December after reports had reached Army Headquarters that some Pakistani troops were escaping into Burma that way. The Task Force consisted of the Headquarters of 2 Corps Artillery Brigade, a battalion and a half of infantry and some supporting troops. It embarked at Calcutta and arrived at its rendezvous with the Eastern Fleet during the night of 13/14 December. There it was transferred to landing craft with some difficulty.

| Editor’s Pick |

The tide conditions being unfavourable, the troops stayed in the landing craft till 0130 hours on 15 December when they finally moved towards the coast. However, the craft could not beach due to sandbars and unsuitable beaches. The troops were then ordered to wade ashore when about a hundred metres or so from land. When the first group jumped into the water, they found it six feet deep. The group happened to be Gorkhas and two of them were drowned. The operation was thereafter halted.

In the morning some country boats arrived on the scene with the news that there were no Pakistanis in the area. The troops were now ferried across in these very boats, a process that took two days. By then the war was over.

Central Sector and the fall of Dacca

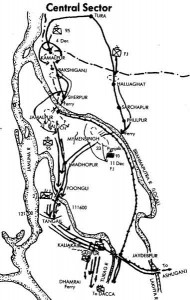

Like the Indians, the Pakistanis had also given the least importance to the Mymensingh-Tangail area. Only their 93 Brigade (with two regular battalions) held it. Even this force was withdrawn at a crucial moment, leaving the way clear for forces initially under Headquarters 101 Communications Zone to reach Dacca before 4 Corps.

The Pakistanis had a stronger delaying position South of Kamalpur, at Bakshiganj. But they withdrew from it without giving much of a fight.

From India the approach into this sector was through Meghalaya; Kamalpur and Haluaghat being the two entry points. The route by way of the former led to Jamalpur, while the latter took one to Mymensingh (see Fig. 13.8). Both Jamalpur and Mymensingh were connected to Dacca by rail and lay on the Southern bank of an off-flow of the Brahmaputra. In its lower reaches this branch of the river is known as the Lakhya. Jamalpur was held by 31 Baluch while Mymensingh had 33 Punjab and Headquarters 93 Independent Infantry Brigade. Both battalions had detachments guarding border posts.

Major General Gill decided to launch his 95 Mountain Brigade under Brigadier H.S. Kler, on the Kamalpur-Jamalpur axis, and FJ Force led by Brigadier Sant Singh, mvc, on the Haluaghat-Mymensingh route. Towards the end of November several attempts had been made to neutralize Kamalpur but its Baluchi garrison had stood firm. Though surrounded it refused to surrender. On 4 December, Kamalpur was subjected to repeated air-strikes. After one such raid, Gill sent a message through a Mukti Bahini volunteer advising the position comrnander to surrender. The latter did not reply as he expected help from his battalion. However, when none came, he surrendered during the evening.

The Pakistanis had a stronger delaying position South of Kamalpur, at Bakshiganj. But they withdrew from it without giving much of a fight. On the morning of 5 December, General Gill went forward to Bakshiganj in a jeep driven by Kler. Unfortunately, the jeep struck a mine and Gill was wounded and evacuated. The same day Major General G.C. Nagra came over from 2 Mountain Division to assume command. He brought with him some of his senior staff, engineer and signal resources from his division.Nagra decided to take Jamalpur with an outflanking move from the West while holding the enemy frontally. Two battalions – 1 Maratha LI and 13 Guards – were to do the outflanking and establish a block South of Jamalpur. They moved manpack, bullock-carts carrying their equipment and guns. The river was crossed about eight kilometres West of Jamalpur.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

However, the slow movement of the bullock-carts led to delay and the leading battalion could hit the Jamalpur-Tangail road only by first light on 9 December. Nagra felt the need for one more infantry battalion to complete the ring round Jamalpur before attacking it. At this stage, Eastern Command came to his help and placed 167 Mountain Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Irani, under him. From this formation 6 Sikh LI joined the two battalions South of Jamalpur in the early hours of 10 December.

Dacca was by this time under threat from the advanced elements of 4 Corps, and Niazi was scraping the barrel for troops to defend it.

The Jamalpur garrison had been under heavy air-strikes and artillery concentrations since 7 December. On 9 December, Kler sent a message through a courier to Lieutenant Colonel Sultan, the commanding officer of the Baluchis, asking him to surrender. In reply he received a bullet together with a note advising him to fight it out instead of writing letters. Kler’s attack on Jamalpur was scheduled for the night of 10 December. Unknown to him the Baluchis were planning to break out that night.

Dacca was by this time under threat from the advanced elements of 4 Corps, and Niazi was scraping the barrel for troops to defend it. Failing to get any from other sectors, he had ordered 93 Brigade to withdraw to Kaliakair, North-West of Dacca. The Brigade Commander, Brigadier Qadir reluctantly passed on this order to his battalions.

With 95 Brigade poised for the attack and the Pakistanis preparing to pull out, a piquant situation developed. Sultan underestimated the strength facing him and in repeated attempts to breakout during the night, his troops suffered heavily. Only small parties managed to get away. More than 380 prisoners were rounded up in the morning. The Pakistani garrison at Mymensingh was able to withdraw unmolested and FJ Force occupied the town on 11 December.

On the afternoon of 11 December, 2 (Para) Battalion Group was dropped about eight kilometres North-East of Tangail. The main task of this group was to cut off the retreat of the Pakistani 93 Brigade by seizing a five-span concrete bridge on the Mymensingh-Tangail road. This was the first major airborne operation by the Past-Independence Indian Army. Several parachute operations had been planned for the Bangladesh campaign but the ground operations went off so well that the other airborne missions were given up.The war in Bangladesh might have ended a few days earlier than it did if this battalion group had landed nearer Dacca and then linked up with the troops of 4 Corps, which were already in Narsingdi. As it was, Tangail was a hundred kilometres from Dacca. When it became obvious that things were moving fast, Major General I.S. Gill, Director of Military Operations at Army Headquarters, did make the suggestion that the venue of the drop be shifted to Kurmitola. The Air Force, however, refused to consider it as the venture was considered too risky. Even the drop at Tangail was scheduled for the night of 11 December and the timing was only later advanced to 1600 hours.

The war in Bangladesh might have ended a few days earlier than it did if this battalion group had landed nearer Dacca and then linked up with the troops of 4 Corps, which were already in Narsingdi.

2 (Para) Group was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel (later Brigadier) Kulwant Singh Pannu and included a Para Field battery, an Engineer platoon and Signal and Medical detachments from 50 (Para) Brigade, as also their equipment and guns. A sharp wind had arisen over Tangail during the afternoon and this spread out the drop. Some of the equipment landed in ponds and one Dakota discharged its load 17 kilometres away from the dropping zone. However, the Group was able to concentrate quickly enough after the drop. The local population was very helpful in retrieving and carrying their stores and equipment.

By the time the para-drop took place, most of Brigadier Qadir’s garrison from Mymensingh had reached Tangail, or gone further down the road to Dacca. He observed the drop from the Circuit House at Tangail, where he was resting at the time, and sent off the nearest company to deal with the paratroopers. The company commander, however, returned after half an hour with the report that it was the Chinese who had landed.The locals had told him this.

About this time Pakistani commanders had been led by their superiors in Islamabad to believe that help was expected from China and the USA. A cryptic message had been passed down saying: ‘friends from the North and friends from the South’ were soon going to intetvene. Though the thought that the paratroopers might be Chinese cheered up Qadir and his companions for a few moments, a little reflection was enough to dispel the misconception. The Brigadier now had two options. He could either take on the paratroopers, very vulnerable at the time of landing, or withdraw to Kaliakair in accordance with his orders. He chose to obey his orders.

| Editor’s Pick |

Unfortunately for him, a stray mine-explosion had occurred a little earlier on the Tangail-Dacca road, a few kilometres South of Tangail. On reaching the scene and hearing some shots, he and the officers and troops accompanying him abandoned their vehicles, split into groups and set out on a cross-country march to Kaliakair.

Meanwhile the paratroopers had captured their bridge and were lying in wait for the enemy. The first to appear was a Pakistani light battery (mortars) around 2030 hours. Its leading vehicle received a direct hit from an anti-tank rocket. Thereafter a larger force made an attempt to dislodge the paratroopers but was driven back with heavy losses. That night and till 1300 hours the next day, the enemy mounted several attacks but they were unco-ordinated actions which cost the enemy dearly. They lost 344 men, killed, wounded and taken prisoner. 2 (Para) Battalion Group’s own losses were light. After 1300 hours on 12 December the Pakistanis began to give the paratroopers a wide berth and took to cross-country paths. At 1700 hours 1 Maratha LI, the leading battalion of 95 Brigade, linked up with the paratroopers.

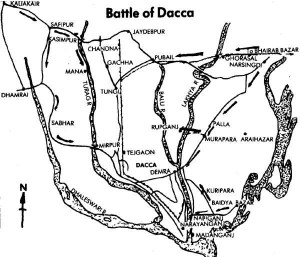

On arrival at Tangail, Nagra decided to push on to Dacca, though he had little transport, except what he had captured and what he could lay hands on locally. The advance began the next morning, 13 December, with 6 Sikh LI in the lead. Kaliakair was cleared around 2200 hours. According to the map with Nagra, two routes now led to Dacca. He could either cross the Turag River and then move by way of Chandna and Tungi, or go by way of Dhamrai and Mirpur (see Fig. 13.9). As the latter route involved the crossing of two rivers, Dhaleswari and the Burhi Ganga, Nagra chose the former. 6 Sikh LI continued their advance throughout the night and came up against the defences on the Turag the next morning. Here the enemy had tanks and advance was held up.

An engineer patrol was now sent to reconnoitre the bridge over the Dhaleswari. It brought the welcome news that a tarmac road, not marked on the Indian map, linked Safipur, South-East of Kaliakair, with the Mirpur Bridge, which lay on the outskirts of Dacca. The patrol also came upon Brigadier Qadir and nine of his officers in a clump of trees. They had taken three days to reach the place. Hungry and exhausted, they surrendered without any fuss.

While keeping the enemy on the Turag fully engaged, Nagra now ordered the rest of his troops in Tangail, including Sant Singh’s force, to join him. While 167 Brigade reinforced 95 Brigade on the Turag, he sent Sant Singh with 13 Guards and a mountain battery on the newly discovered route. 2 (Para) Battalion also advanced from Tangail on 15 December and by the evening they had joined Sant Singh.

At 2200 hours that night the paratroopers took up the advance, reached the vicinity of the Mirpur Bridge around 0200 hours on 16 December and sent out a patrol. When it was halfway across the bridge the Pakistanis on the far end opened up and two of the patrol’s jeeps were shot up. The rest of the patrol returned to the near end of the bridge.

At 2200 hours that night the paratroopers took up the advance, reached the vicinity of the Mirpur Bridge around 0200 hours on 16 December and sent out a patrol. When it was halfway across the bridge the Pakistanis on the far end opened up and two of the patrol’s jeeps were shot up. The rest of the patrol returned to the near end of the bridge.

THE SURRENDER

By this time orders had already gone out from Niazi’s Headquarters to his subordinate commanders to cease fire and surrender. But these orders took time to reach the troops. According to Pakistani evidence, Niazi had lost heart within a few days of the commencement of the war. He is said to have broken down completely when he went to meet Governor Malik on 7 December.19 After the meeting Malik sent a message to President Yahya Khan to arrange a cease-fire but there was no response from Islamabad.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

Niazi’s despondency was shared by some of his commanders and senior advisers. Another communication was sent to Yahya Khan three days later, suggesting a political settlement and cease-fire. In reply the President delegated the authority for further action to the Governor. The latter got in touch with Paul Mark Henry, Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations, who happened to be in Dacca at the time, and handed him a note. It called upon the UN to arrange, among other things, an immediate cease-fire, transfer of power to elected representatives of the people of East Pakistan and repatriation with honour of Pakistani Armed Forces to West Pakistan. When this note reached New York its contents received wide publicity. This upset Z.A. Bhutto, who was at the time pleading Pakistan’s case at the UN. He hoped to obtain better terms and this prompted the Pakistani Government to disown Malik’s note.

It called upon the UN to arrange, among other things, an immediate cease-fire, transfer of power to elected representatives of the people of East Pakistan and repatriation with honour of Pakistani Armed Forces to West Pakistan.

It was about this time that the rumour about intervention by friends from the North and friends from the South’ was spread. We have seen its effect at Tangail. It did bolster the flagging spirits of the Pakistani troops for a day or two. But in retrospect, it would seem to be a very questionable way of boosting morale. The subsequent disillusionment must have hurt the prestige and credibility of Pakistani commanders.20

According to Niazi’s original plan, Dacca was to have a double line of defences: an outer line and an inner line. These defences were to be manned by formations falling back from various sectors. When none of them managed to do so, all available men in uniform were mustered for the task. Only about 1,500 regular soldiers, including services personnel, could be got together. In addition, about 3,500 police and paramilitary personnel were available. Surplus staff officers and others pulled out from offices and depots were sent to command the groups and detachments into which these men were divided. To support this last-ditch stand were a few mortars and recoilless guns, a squadron of tanks, two six-pounder anti-tank guns and some light machine guns. However patriotic and brave they might be, this motley collection of men and arms could not have kept the Indian divisions out of Dacca for long.

These men were not given much of a chance either. Niazi’s senior staff officers and the Governor’s chief advisers had lost the will to fight. On 12 December, another urgent message had gone to the President of Pakistan to save ‘innocent’ lives. There was no reply from him till 14 December. That day, a high-level meeting was scheduled at the Government House in Dacca, at which Dr Malik was to preside. A radio intercept alerted the Indian authorities and while the meeting was on, the Government House was raided by Indian aircraft. The roof of its main hall collapsed and Dr Malik rushed to the air-raid shelter and wrote out his resignation. Soon after, the Governor, his cabinet and senior civil servants, including West Pakistanis, moved to the neutral zone, which had been created by the International Red Cross at the Hotel Intercontinental.

Niazi also received a message that day from Yahya Khan to end the hostilities. However, when he requested the US Consul-General in Dacca to negotiate a cease-fire, that official refused to undertake the mission, but agreed to send Niazi’s message. Addressed to General Manekshaw, the message asked for an immediate cease-fire. It reached New Delhi via Washington.

This upset Z.A. Bhutto, who was at the time pleading Pakistans case at the UN. He hoped to obtain better terms and this prompted the Pakistani Government to disown Maliks note.

Manekshaw was himself keen to end the hostilities. He had been making repeated calls in broadcasts to Pakistani forces in East Pakistan to surrender. Leaflets in Urdu, Pushtu and Bengali were also dropped. His reply to Niazi was, however, quite firm. It stated that cease-fire would be acceptable provided the Pakistani Armed Forces in Bangladesh surrendered to the advancing Indian troops by 0900 hours on 16 December. He also gave the radio frequencies on which the Pakistani GOC-in-C could contact General Aurora’s Headquarters to co-ordinate the surrender. As a token of good faith he made it known that all action over Dacca would cease from 1700 hours on 15 December. At Niazi’s request the deadline for the surrender was later extended to 1500 hours on 16 December. His Headquarters sent out a signal around midnight (15/16 December) to lower formations to contact their Indian counterparts and arrange the cease-fire.

Returning to the Mirpur Bridge on the morning of 16 December, we find the paratroopers still on its Western end. Kler’s Headquarters had picked up Niazi’s radio signal to his commanders and he told Nagra of it when the two met that morning. It was good news and the exhilaration of victory that suffused Indian commanders and troops was very natural. But in their enthusiasm to set foot in Dacca without loss of time, some of them overlooked the fact that the two armies had been fighting an all-out war; unless precautions were taken casualties could arise. Pakistani and Indian troops had not been briefed as yet regarding the modalities of surrender.

Around 0830 hours Nagra sent his ADC and some officers from 2 Para with a message for Niazi, asking him to surrender. Their jeep was flying a white flag. When the jeep reached the Pakistani defended post at the Eastern end of the Mirpur Bridge, the post commander took Nagra’s message and sent it on to Niazi’s Headquarters. While the Indian officers waited for a reply the Pakistanis served them tea. A short while later, Major General Jamshed, Area Commander of the Dacca area, arrived for a meeting with Nagra.

| Editor’s Pick |

The Indian jeep now led Jamshed’s car to the other side of the bridge. While halfway across, the paratroopers accidentally opened fire on the jeep. Some of them had moved to a flank of the bridge after the jeep carrying Nagra’s message had gone across. The white flag on the jeep had been removed while the party was with the Pakistanis on the other side. The firing resulted in the wounding of one Indian and one Pakistani officer. Later during the day there were other incidents of this nature, some more serious. In fact, fighting around Dacca continued till late in the afternoon.

The surrender ceremony at Dacca took place during the afternoon. There was hardly anything “˜military about it, except the guard of honour provided by 2 Para and a small Pakistani contingent.

Nagra drove to Niazi’s Headquarters around 1100 hours. About the same time 2 Para, followed later by units of 95 Brigade, entered Dacca. Jubilant crowds welcomed them with garlands and shouts of Joi Bangla and Indira Gandhi Ki Jai. Major General (later Lieutenant General) J.F.R. Jacob, Aurora’s chief of Staff, flew into Dacca at 1300 hours with the draft instrument of surrender. It covered all of Pakistan’s Armed Forces in Bangladesh, including her Navy and Air Force, and Paramilitary personnel. It also guaranteed the rights of prisoners under the Geneva Convention, as also the protection of foreign nationals, ethnic minorities and people of West Pakistani origin.

The surrender ceremony at Dacca took place during the afternoon. There was hardly anything ‘military’ about it, except the guard of honour provided by 2 Para and a small Pakistani contingent. A million Bangladeshis, jostling and shouting slogans, watched as Lieutenant General Aurora21 inspected the two guards of honour. When Niazi and Aurora sat down to put their signatures to the instrument of surrender, an Indian Air Marshal, a Vice Admiral and Corps Commanders stood in a huddle behind them, with sundry civilians looking over their shoulders.

After he had put his signature to the surrender document Niazi took out his revolver and handed it over to Aurora. Pakistani troops were not, however, disarmed straightaway. They were allowed to retain their weapons for their own protection till Indian troops were available in sufficient numbers to take control. In other sectors, surrenders took place under local arrangements and continued for a few days after the cease-fire. Of a total of 91,000 prisoners, 56,694 belonged to the armed forces, 12,192 were paramilitary personnel and the rest civilians. During the last hours of the shooting war an aviation squadron (helicopters) of the Pakistan Army had flown out about two dozen families, Major General Rahim Khan and some others to Akyab, in Burma. Thence they travelled to Karachi. Indian casualties in the campaign totalled 5,586: 1,525 killed 4,061 wounded.22

After he had put his signature to the surrender document Niazi took out his revolver and handed it over to Aurora. Pakistani troops were not, however, disarmed straightaway. They were allowed to retain their weapons for their own protection till Indian troops were available in sufficient numbers to take control. In other sectors, surrenders took place under local arrangements and continued for a few days after the cease-fire. Of a total of 91,000 prisoners, 56,694 belonged to the armed forces, 12,192 were paramilitary personnel and the rest civilians. During the last hours of the shooting war an aviation squadron (helicopters) of the Pakistan Army had flown out about two dozen families, Major General Rahim Khan and some others to Akyab, in Burma. Thence they travelled to Karachi. Indian casualties in the campaign totalled 5,586: 1,525 killed 4,061 wounded.22

NOTES

- The account of the meeting as given here is based on the author’s interview with Field Marshal Manekshaw in January 1979.

- Interview with author.

- Witness to Surrender, by Lieutenant Colonel S. Salik, p. 118.

- Ibid p. 116.

- Ibid, p. 116.

- The Liberation of Bangladesh, by Major General Sukhwant Singh, p. 72.

- The commanding officer of 14 Punjab and the squadron commander of 45 Cavalry, who supported the battalion, were awarded the Maha Vir Chakra.

- Pakistan Cut to Size, by D.R. Mankekar, p. 40.

- The battalion won three Maha Vir Chakras during the two battles.

- 50 Independent (Para) Brigade (less a battalion group) was later flown out to the Western theatre.

- India’s Sword Strikes in East Pakistan, by Major General Lachhman Singh. p. 53.

- Victory in Bangladesh, by Major General Lachhman Singh, pp. 76-8.

- The commanding officer of the Guards’ battalion and one of his platoon commanders were awarded the MahaVir Chakra for gallantry in this action.

- Witness to Surrender, by Lieutenant Colonel Salik, p. 153. The author writes of Charkai as Ghirai.

- Some days earlier 20 Mountain Division had been ordered to part with 63 Cavalry and 340 Brigade; the former was to move to the Western theatre and the latter to Dacca along with a squadron of 69 Armoured Regiment. However, the move could not take place in the absence of ferry facilities over the Brahmaputra.

- It is of interest that among the Indian generals who fought in Bangladesh, there were four paratroopers: Lieutenant General J.S. Aurora, Lieutenant General Sagat Singh, Lieutenant General T.N. Raina, Major General B.F. Gonsalves. Major General I.S. Gill, Director of Military Operations at Army Headquarters, was also a paratrooper.

- This rifleman won the Maha Vir Chakra, besides which the battalion won two Vir Chakras and one Sena Medal in this action.

- These figures are from Victory in Bangladesh, by Major General Lachhman Singh. According to Lieutenant Colonel Salik (Witness to Surrender) 311 Brigade abandoned seven tanks in running condition.

- Witness to Surrender, by Lieutenant Colonel Salik, p. 194.

- A task force from the Seventh Fleet of the United States did enter the Bay of Bengal on 14 December. The US Government declared at the time that it was meant for an ‘evacuation contingency’ to rescue American citizens in Bangladesh. However, Henry Kissinger, special assistant to the US President, later gave out that the move of the task force was a part of gunboat diplomacy to exert pressure on India. The aim, according to him, ‘was to stop India from destroying West Pakistan’.(White House Years, by Henry Kissinger)

- Lieutenant General Aurora came to Dacca accompanied by Mrs Aurora. This was perhaps the only instance in military history of a victorious commander taking his wife to witness a surrender.

- Figures from ‘The Fall of Dacca’, an article by Lieutenant General J.S. Aurora in The Illustrated Weekly of India, dated 23 December 1973.