The attack came a few minutes after midnight. The Kumaonis stuck to their positions, their mortars taking a heavy toll of the enemy. Around 0300 hours the fighting ceased. ‘The silence all round gave the impression that the Chinese had withdrawn. But they hadn’t. Under cover of the dark, they silently infiltrated on the flanks and the rear of the Indian positions. At first light they attacked again’. The fighting now became intense. However, as it was not possible to reinforce Mohan Ridge, the troops there and at Dichu were ordered to fall back on Kibithu, a village lying three kilometres South of the McMahon Line.The intermixing of companies made little sense to anyone, especially the fighting troops. No commander made the necessary readjustments both to the defensive layout as well as to the command and control set-up. The brigades’ dispositions were essentially linear with no depth.

The attack came a few minutes after midnight. The Kumaonis stuck to their positions, their mortars taking a heavy toll of the enemy. Around 0300 hours the fighting ceased. ‘The silence all round gave the impression that the Chinese had withdrawn. But they hadn’t. Under cover of the dark, they silently infiltrated on the flanks and the rear of the Indian positions. At first light they attacked again’. The fighting now became intense. However, as it was not possible to reinforce Mohan Ridge, the troops there and at Dichu were ordered to fall back on Kibithu, a village lying three kilometres South of the McMahon Line.The intermixing of companies made little sense to anyone, especially the fighting troops. No commander made the necessary readjustments both to the defensive layout as well as to the command and control set-up. The brigades’ dispositions were essentially linear with no depth.

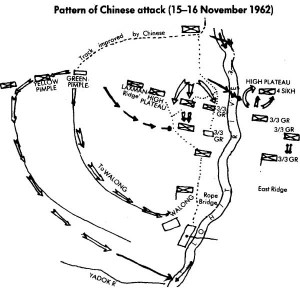

The Chinese held two features, Green Pimple and Yellow Pimple, facing the Kumaonis’ forward locality in the far West. During the lull, they had built a track to these positions under cover of the intermittent shelling that marked the period. From observation posts on these hills, they were able to bring down accurate fire on Indian defences from their mortars and artillery. To deprive the enemy of this advantage, Rawlley ordered 6 Kumaon to capture Green Pimple. However, the Kumaonis’ assault, put in on 6 November, did not succeed.

The Chinese had attacked the Ladders on the morning of 15 November, but suffered heavily in a frontal assault.

The Pimples’ area was obviously the base for the Chinese attack by infiltration on the Western flank. Rawlley, therefore, ordered another attack, again on Green Pimple. Again the task was given to the Kumaonis, with the Sikhs making a diversionary manoeuvre. The attack went in on 14 November. Despite heavy opposition, the Kumaonis were able to reach within 50 metres of their objective. However, the enemy held them there; he had bunkers near the top of the hill. Around 1700 hours, Rawlley ordered the battalion to stand firm in its positions.

Shortly before midnight, the enemy counter-attacked. The Kumaonis’ assault companies were encircled and they could break out only after bitter fighting. The remnants reorganized at a feature called Trijunction, which had been the base for this operation. This position also came under attack soon after but the Kumaonis held their ground. On the morning of 15 November, the Chinese attacked Trijunction a second time but were again repulsed.

The previous day, 4 Dogra had begun to arrive at Walong. A company of this battalion and the men collected from other Kumaoni localities (which the Dogras had taken over) were rushed to Trijunction on the night of 15/16 November. Thus reinforced, Trijunction repulsed two more attacks. The fate of Walong, however, was by then sealed.

Around 0300 hours on 16 November the Chinese began a series of co-ordinated attacks on both sides of the Lohit River. Combined with the frontal attacks was an enveloping move from the West. Their aim was to reach the air-strip and the junction of the Lohit with the Yepak River, both South of Walong, so as to cut off the Indians’ retreat. Indian troops fought with determination but superior numbers and better weapons carried the day.

| Editor’s Pick |

At their company localities, 4 Sikh withstood enemy attacks with great courage. Regardless of the odds, they fought on; in some cases whole platoons were wiped out but did not surrender. The Gorkhas fought their hardest action at the Ladders’ position. This locality on the Kibithu-Walong track, which ran along the West bank of the Lohit, got its name from the steps cut into a vertical rock-face. The Gorkhas’ bunkers in this position were virtually rock-caves, impervious to artillery fire from the West bank. Indian Para field guns and mortars and medium machine guns, placed East of the Lohit, supported this position. As long as the Indian defence East of the river held out, the Ladders’ position was safe.

The Chinese had attacked the Ladders on the morning of 15 November, but suffered heavily in a frontal assault. Thereafter, they began to blast the Gorkhas’ bunkers with bazooka fire. They attacked Ladders again that night but were beaten back. The company commander now asked 4 Sikh for reinforcements as the company was under command of that battalion. However, the Sikhs were themselves hard-pressed and could not spare any men.

The withdrawal order did not reach them and most of them were taken prisoner.

On the morning of 16 November, the Gorkhas at the Ladders could watch the attack develop on the Sikhs’ position East of the river. The Chinese crossed over for the attack in large numbers from the West bank in their rubber dinghies. By 0800 hours they had overrun the Sikhs’ company position. Then they placed their direct fire support weapons on the East bank and began to shell Ladders. One by one, the Gorkhas’ bunkers were knocked out but the survivors stayed put. The withdrawal order did not reach them and most of them were taken prisoner.

Due to the manner in which the Indian positions were sited, an orderly withdrawal was out of the question. The battle ended with the Gunners of 17 (Para) Field Regiment firing off their remaining ammunition from their gun-positions on both sides of the Lohit. The Heavy Mortar Battery had earlier abandoned its pieces when the Chinese advanced towards its positions since it had run out of ammunition completely (see Fig.). The withdrawal order was given by Rawlley at 1100 hours on 16 November.

Brigadier Rawlley intended to make a stand on the Yepak but the Chinese forestalled him.

Brigadier Rawlley intended to make a stand on the Yepak but the Chinese forestalled him.

“They were already there and ambushed the withdrawing troops. It was here that the Chinese took most of their prisoners; units broke up into small parties and the long trek to Teju began. The leading troops arrived there on 24 November. When a count of heads was carried out at Teju on November 27, a total of 1,843 all ranks were present with 11 Brigade”.30

The trek from Walong was arduous. Many of the men had to go without food for several days. Stragglers continued to join their units for some days. The Chinese ended their pursuit of the withdrawing troops short of Hayuliang.

As for the remaining two frontier divisions of NEFA, the Chinese entered the Siang Divisions on 16 November and took Gelling, Tuting, Machuka and some other posts in its Northern portion. In the Subansiri Division, they overran the Indian posts at Asafila, Tasking and Limeking.31

LADAKH

It is refreshing to turn to Ladakh from the unrelieved litany of disasters in NEFA. Here too the Chinese took what lay within their claim-line. But good leadership ensured that men were not ordered to shed their blood in defence of territory that was of no tactical importance. At the same time, the enemy was made to pay heavily for his gains. The Indian Army is justly proud of the gallantry shown by the officers and men of 114 Brigade at the Battle of Chushul.

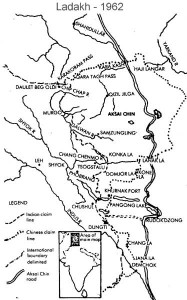

We have earlier noted how Western Command had asked for an infantry division with four brigades and supporting arms to meet the Chinese on equal terms. However, till the end of September 1962, Ladakh had only 114 Infantry Brigade with two regular battalions – 1/8 Gorkha Rifles and 5 Jat. These two battalions and the Jammu & Kashmir Militia were strung out on posts and picquets throughout Ladakh, from Daulet Beg Oldi in the North to Demchok in the South (see Fig. 9.5). Most of these posts were there only to show possession of territory. In case of hostilities, all they could do was to serve as warning posts. Brigadier T.N. Raina (later General Raina, mvc) took over command of 114 Brigade in the third week of September.

According to the Indian Government’s estimate, the Chinese were not expected to react strongly in Ladakh to Operation ‘Leghorn’. Hence the lack of promptness in reinforcing this sector. The first indication of this was the arrival of 13 Kumaon at Leh on 2 October, together with a platoon of 1 Mahar (machine guns). Even at this stage, there was no inkling of Chinese designs and 13 Kumaon was told that it might move to Chushul in March 1963.When the Chinese struck in the early hours of 20 October, Indian troops at the higher posts had already begun their annual thinning out for the winter. The attacks came simultaneously against many of the forward posts. In the North, the posts on the Chip Chap River, East of Daulet Beg Oldi, were among the first to be attacked. The Jammu & Kashmir Militia, who were manning them, fought stubbornly. But the Chinese had brought up enough strength to overwhelm them and they were ordered to withdraw to Daulet Beg Oldi. Two days later, when the Chinese threatened to encircle Daulet Beg Oldi, the garrison there was told to withdraw along the Chip Chap and Shyok Rivers to lay back positions at Thoise, North of Leh.

According to the Indian Government’s estimate, the Chinese were not expected to react strongly in Ladakh to Operation ‘Leghorn’. Hence the lack of promptness in reinforcing this sector. The first indication of this was the arrival of 13 Kumaon at Leh on 2 October, together with a platoon of 1 Mahar (machine guns). Even at this stage, there was no inkling of Chinese designs and 13 Kumaon was told that it might move to Chushul in March 1963.When the Chinese struck in the early hours of 20 October, Indian troops at the higher posts had already begun their annual thinning out for the winter. The attacks came simultaneously against many of the forward posts. In the North, the posts on the Chip Chap River, East of Daulet Beg Oldi, were among the first to be attacked. The Jammu & Kashmir Militia, who were manning them, fought stubbornly. But the Chinese had brought up enough strength to overwhelm them and they were ordered to withdraw to Daulet Beg Oldi. Two days later, when the Chinese threatened to encircle Daulet Beg Oldi, the garrison there was told to withdraw along the Chip Chap and Shyok Rivers to lay back positions at Thoise, North of Leh.

On the Northern shore of the Pangong Lake, India had two posts at Sirijap. They formed the first line of defence of Chushul from the North and were thus of vital importance. Held by a company of 1/8 Gorkha Rifles under Major Dhan Singh Thapa, Sirijap came under fierce attacks from the Chinese on 21 October. The Gorkhas threw back the first attack which was launched after heavy shelling. Though the enemy suffered heavily, it came back in larger numbers after more shelling. The Gorkhas beat back this attack as well.By then casualties had greatly depleted the Gorkha company. The men under Dhan Singh Thapa were, however, a determined lot. When the Chinese attacked once again, they continued to give battle as long as any of them remained on their feet. When the position was finally overrun, Dhan Singh Thapa got out of his trench and killed several of the enemy before he was overpowered and taken prisoner. His courage and exemplary leadership won Dhan Singh Thapa India’s highest award for gallantry. This was the first award of the PVC in Ladakh. Only seven men came back from Sirijap.

On the Northern shore of the Pangong Lake, India had two posts at Sirijap. They formed the first line of defence of Chushul from the North and were thus of vital importance. Held by a company of 1/8 Gorkha Rifles under Major Dhan Singh Thapa, Sirijap came under fierce attacks from the Chinese on 21 October. The Gorkhas threw back the first attack which was launched after heavy shelling. Though the enemy suffered heavily, it came back in larger numbers after more shelling. The Gorkhas beat back this attack as well.By then casualties had greatly depleted the Gorkha company. The men under Dhan Singh Thapa were, however, a determined lot. When the Chinese attacked once again, they continued to give battle as long as any of them remained on their feet. When the position was finally overrun, Dhan Singh Thapa got out of his trench and killed several of the enemy before he was overpowered and taken prisoner. His courage and exemplary leadership won Dhan Singh Thapa India’s highest award for gallantry. This was the first award of the PVC in Ladakh. Only seven men came back from Sirijap.

The Galwan Post had been taken over by 5 Jat in the first week of October. The Chinese had wiped out this post. Kongka, which had been in the news in 1959, suffered the same fate. The Hot Springs Post was withdrawn, and Demchok also fell.

Prior to the invasion, the airfield at Chushul seldom received more than one aircraft a day. It had now to cope daily”¦

After the fall of Sirijap, it was decided that the troops North of the Pangong Lake should withdraw. Two storm boats of 36 Field Company assisted the withdrawal. Under enemy fire, they ferried the troops at night across the lake. Unfortunately, one of the boats sank after being hit.

At this stage, Lieutenant General Daulet Singh appreciated that Chushul would be the next enemy objective. It had an all-weather airfield and lay on the route to Rudok, a hundred kilometres to the East as the crow flies. The Chushul Valley is a narrow sandy tract at an altitude of 4,337 metres. At its Northern end is the beautiful Pangong Tso (Lake). On its East and West, the valley is flanked by lofty ranges that rise up to 5,790 metres. There is a parting in the mountains in the East: the Spanggur Gap. Over it runs the route to Rudok, skirting another gorgeous lake, the Spanggur Tso. The Chinese, in their pre-invasion activity, had improved the track right up to the Spanggur Gap. It could even take tanks, The Chushul airfield was near the Southern end of the valley not far from the mouth of the Gap.

When,,,, photo of Brigadier Hoshiar Singh shown to one of the pow after his sacrifice,,, the chinese officer asked …. do you know this officer ?… he is now …no more…

face of indian Jwan got SHOCKED,,,

oh !!! u know this man…tell me about him…

…he replied… his wardi shows …..

he is an indian officer …we salute and proud of him.

jai hind….

to immediate officer of this jawan… who really remembers his great hero till now. .

I visited NEFA IN 1987 after a gap of 25 years of operations and had carried out recovery operations of equipment after declaration of ceasefire by Chinese.

When I was visiting Rupa few people stationed there showed the place where Brigadier Hoshair Singh was tied behind a Chinese Jeep and dragged till he passed away.

While reading one of the accounts it said that he was shot dead.

What is the truth ?