Chinese counter-action, which Kaul had foreseen, came on 10 October. That day at dawn, Kaul was shaving outside his bunker and his batman was boiling water for tea, when the calm of the Namka Chu Valley was shattered all of a sudden. The Punjabis at Tseng-jong were under attack.

It was the Punjabis’ routine morning patrol that was first engaged by the Chinese. Later, around 0800 hours, a full battalion tried to overwhelm the isolated locality. Only 56 of the Punjabis were holding the area, but they fought back the attack. An hour later, the Chinese re-formed for a second attack. By then, the Punjabis’ section on the spur of Karpo La II had moved close to the flank of the Chinese forming-up place. While the latter were bunched together this section let them have it. The Chinese suffered heavy casualties and reacted by opening up with heavy mortars.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

When the first shots rang out, the Rajputs were strung along the South bank of the Namka Chu. They were on their way to the crossing place whence they would climb to Yumtso La. Their forward company was approaching Temporary Bridge and the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel (later Brigadier) Maha Singh Rikh, was following the second company. When he reached Bridge IV, he saw Kaul. With him were Niranjan Prasad, Dalvi, Brigadier (later Lieutenant General) K.K. Singh,12 Brigadier (later Major General) M.R. Rajwade,13 and some other members of Kaul’s staff. Kaul called Rikh over to him and ordered him not to advance further.

“¦ the Chinese had not been idle. Their preparations for a showdown were in evidence all along the McMahon Line and in Ladakh.

He said that the situation had changed and the Chinese had reacted more violently than he had anticipated. He then told Rikh that his battalion would hold the South bank with one company each at Bridges III and IV and Temporary Bridge. When Rikh pointed out that these positions were dominated by the Chinese and would be impossible to hold in case of attack, Kaul told him that the Chinese would not attack if the Indian troops remained on the South bank. He then added that in any case, after a few days, the Indian offensive would be resumed.

Having given these orders, Kaul turned to Dalvi. “It is your battle” he told him. Having exercised personal command on the front since his arrival on 6 October, he was handing back the brigade to its commander. He had decided, he said, to go to Delhi and place before the COAS and the Government ‘a first-hand account of the situation’. Senior commanders have been known to assume personal command of operations in a crisis. For example, Auchinleck after Sidi Rezegh. Here Kaul was relinquishing personal command in a crisis. Also, field commanders do not have to rush from the battlefield to give first-hand accounts to the Government. He could have sent a report through a courier; after all his chief staff officer was with him on the spot. But he chose to go himself.

Kaul and his party, including Niranjan Prasad, left around 1000 hours. They went by the Hathung La route; dalvi had, therefore, to pull out a company of the Gorkhas to escort them part of the way. By dusk, the party was at the foot of Hathung La. Kaul spent the night there in great pain; he had developed pulmonary oedema. It was the result of disregarding the basic precautions of acclimatizing himself before venturing on to high altitude areas. He had to be carried across Hathung La next day and by the time he left Tezpur, he was running a temperature.

At Tseng-jong, the Chinese attacked again at noon. Major M.S. Chowdhary, the company commander, had been asking for mortar and machine-gun fire support but Dalvi decided against such a course. He felt that such fire would escalate the skirmish into a full-scale battle and imperil the Rajputs on the river. He, therefore, ordered Chowdhary to disengage and withdraw. By then, the Chinese were into the locality and hand-to-hand fighting had begun. Chowdhary was wounded but he displayed remarkable courage and leadership in extricating the remnants of his two platoons. Man for man, the Punjabis gave a good account of themselves. One of them brought back a Chinese rifle. The skirmish cost them 22 killed, wounded and missing. Peking radio admitted to a 100 casualties.

Soon after the outbreak of firing on Tseng-jong, Dalvi had recommended to Kaul and Niranjan Prasad to take a realistic view of the situation and withdraw the brigade to a more defensible position”¦

The Indian Press and Government spokesmen highlighted the skirmish. No doubt Indian troops made a good showing but it was not something to crow over. In fact, the Chinese had held their hand. They could have cut the Punjabis’ route of withdrawal but they allowed them to pull out and take back their wounded. Obviously they wanted to give the impression that they did not want war. Later that day, the Chinese buried the Indian dead with full military honours. Indian troops on the South bank could watch the scene; they were impressed, though it was all done as part of Chinese propaganda.

Soon after the outbreak of firing on Tseng-jong, Dalvi had recommended to Kaul and Niranjan Prasad to take a realistic view of the situation and withdraw the brigade to a more defensible position, leaving flag-posts on the Namka Chu. However, Kaul told him before leaving that Operation ‘Leghorn’ was to be held in abeyance but there was to be no withdrawal from the positions already held.

On arrival in Delhi, Kaul attended a meeting on the night of 11 October at the Prime Minister’s house. Present at the meeting, besides Nehru, were Menon, the Secretaries of the Cabinet, External Affairs and Defence, the COAS, the Air Chief and Sen. After Kaul had made his report, various courses of action were discussed. According to Kaul, the decision that was finally taken was to cancel the eviction order but stick to the positions held at the time.14 Kaul returned on 13 October to Tezpur and conveyed the decision to all concerned.

Meanwhile, events had taken a curious turn. On the morning of 12 October, Nehru left for Colombo to attend a conference. At the airport, newsmen asked him about India’s future course of action with regard to the Chinese occupation of Thag La. The Prinie Minister’s reply was a guarded statement on the situation but the key words said to have been spoken by him, “our instructions are to free our territory”, were reported by some papers as ‘the armed forces have been ordered to throw the Chinese aggressors out of NEFA’. All India Radio too broadcast Nehru’s statement on 12 October. In some quarters, the Prime Minister’s words were construed as a declaration of war.

| Editor’s Pick |

The statement at the airport astonished those who had attended the Prime Minister’s meeting the previous night. Kaul was later to say: “I wonder if Nehru’s statement did not precipitate their [Chinese] attack”.15 It certainly riled the Chinese. Later, during his captivity in China, Dalvi was confronted with questions like ‘How can Indians talk of throwing out the Chinese People’s Army when even a mighty power like the United States had not been able to do that?’

Looking back, it seems there was substance in what the Prime Minister had said. Indications soon came that the Government did want the eviction operation to be put through. On 16 October, 4 Corps received fresh instructions. According to these, the locality at Tsangle was to be built up to a battalion, aggressive patrolling was to be undertaken and the requirements for the eviction operation were to be submitted. Dalvi has stated that the Defence Minister specified 1 November as the ‘last date acceptable to the Cabinet’ for the operation.16 Apparently, either the situation on the Namka Chu was not sufficiently clear to the political leadership, or the country was being put on a suicidal course by someone who worked behind the scenes.

For their part, the Chinese had not been idle. Their preparations for a showdown were in evidence all along the McMahon Line and in Ladakh. However, for the moment, we shall confine ourselves to events in the Kameng sector. The Chinese had occupied Tseng-jong and a feature East of Tsangle in strength. Mules were bringing their mortars and machine guns right up to the river and they were strengthening their positions with wire and panjis (bamboo stakes sharpened at one end). On the night of 15/16 October, they began to probe the Indian positions at Tsangle and Bridge V. Two nights later (17/18 October), they brought them under heavy fire for 90 minutes.

On 19 October, there were unmistakable signs that an attack was imminent. Large numbers of mules were seen coming across Thag La to the North bank of the Namka Chu, carrying stores and equipment. An observation post of the Rajputs counted about 2,000 Chinese coming down and concentrating below Tseng-jong. Their marking parties could be seen at work, preparing for night attacks.

By then, much had happened South of the Namka Chu also. 4 Grenadiers, which had earlier arrived at Towang, was placed under the command of 7 Brigade. It had come as poorly equipped as the others and was the least acclimatized unit. Dalvi had established his Headquarters at Rong La, less than a kilometre from the Assam Rifles’ post at Che Dong.Tactical Headquarters 4 Division had moved to Ziminthang and the Signals had completed the laying of telephone lines connecting Tsangdhar with most of the positions on the river. Between 13 and 16 October, about 450 pioneers from the Border Roads Organization arrived. To Dalvi, they proved more of a headache than a help. They came without snow-clothing and had to be provided essential items by withdrawing these from the troops. This was naturally resented by the latter. Within a few days, 50 per cent of the pioneers were on the sick-list.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

The 9 Punjab company at Tsangle was a big drain on Dalvi’s slender resources. He had repeatedly sought permission to withdraw it as he thought that it would be the first objective of the Chinese if they attacked; also, they could easily cut it off. Kaul knew these difficulties, and had represented against the order from Army Headquarters for deploying another battalion at Tsangle. He had, in fact, recommended the withdrawal of the company there to the South bank. This had brought Menon to Tezpur on the morning of 17 October. With him were Thapar and Sen. Kaul tried to convince the Defence Minister that it would be impossible to maintain Tsangle during the winter. Menon overruled him, saying that ‘it was politically important’ to hold Tsangle as it was situated near the point where the borders of Bhutan, Tibet and India met.17

It has been estimated that the Chinese employed two infantry divisions and a specially trained formation in Kameng of this force, they used one division against 7 Brigade.

That evening, after he had seen off Menon and his party, Kaul was taken ill. He was evacuated to Delhi the next day. The departure of the corps commander at this juncture was unfortunate. But the mishap had even more serious consequences when, on arrival in Delhi, he did not go into hospital but went straight to his residence, whence he continued to exercise command over 4 Corps. According to Army rules, when a commander becomes a casualty and is evacuated, as Kaul was, his functions devolve upon the next senior. But in the Army of 1962, a person with Kaul’s connections could get away with anything.

Dalvi had been faithfully reporting Chinese preparations to Niranjan Prasad. On 17 October, he requested that he be allowed to withdraw, brigade from the Namka Chu quickly as he could not maintain his troops there. Niranjan Prasad promised to speak to the corps commander but the latter had meanwhile been evacuated. The next day, Dalvi received an order to immediately send a company from 1/9 Gorkha Rifles to Tsangle. The rest of the battalion would follow. This was in compliance with Menon’s instructions; for Dalvi, it was the proverbial last straw on the camel’s back. He urged against the move. The protest was relayed to Kaul in Delhi; the reply was that any officer who failed to obey orders would be court-martialled.

On 19 October, when he could see the Chinese giving the final touches to their preparations for an attack, Dalvi made a last bid to save his troops from massacre. He urged Prasad to permit a tactical redeployment of 7 Brigade to meet the expected attack. He told the GOC that rather than stand and watch the slaughter of his men, he was prepared to resign his commission. However, all Niranjan Prasad could do was to convey Dalvi’s request to 4 Corps. Brigadier K.K. Singh told him that he had no authority to sanction the change that Dalvi wanted but would get in touch with the corps commander in Delhi for orders. When Niranjan Prasad conveyed this information to Dalvi, the latter asked to be relieved of his command immediately as he was not prepared to continue in a situation in which the actions of his superiors had placed his troops. According to Dalvi, Niranjan Prasad was so overwhelmed with emotion at this that he broke down and promised to be with him the next morning ‘to share the fate of the brigade’.18

Fortunately for him, Niranjan Prasad did not visit the Namka Chu on 20 October, otherwise he might have shared Dalvi’s fate and given a chance to the Chinese to have an Indian general as a prisoner of war. Dalvi’s forecast regarding the attack proved correct. It came at 0500 hours with 150 guns and heavy mortars roaring in unison to announce it. The previous night, the Chinese had gone into their forming-up places on commanding ground. They made no attempt to hide their positions from the Indians facing them across the narrow stream, which was now fordable. They even lit fires to keep themselves warm.

“¦the Chinese chose to effect a breakthrough in its centre with outflanking attacks by infiltration against Tsangdhar and Hathung La.

It has been estimated that the Chinese employed two infantry divisions and a specially trained formation in Kameng of this force, they used one division against 7 Brigade. Its mission was to advance on Towang after finishing off the brigade. At Towang, it was to link up with a division advancing from Bum La. For dealing with 7 Brigade, the Chinese chose to effect a breakthrough in its centre with outflanking attacks by infiltration against Tsangdhar and Hathung La. With these key features in their hands, the rest of the troops on the Namka Chu could be dealt with at leisure.

At Rong La, the Headquarters, besides the usual ancillaries, Dalvi had 100 Field Company and a company of 1/9 Gorkha Rifles. On his right, at Bridge I, he had the Grenadiers, less two companies. The battalion had a company each at Drokung Samba and on the lines of communication at Serkhim. The Punjabis, less their company at Tsangle, held Bridge II. The remaining bridges, except for Bridge V, were held by the Rajputs. The Gorkhas were deployed astride the Tsangdhar-Che Dong track with a company (less a platoon) at Tsangdhar. A platoon of this company was on its way to Tsangle in compliance with the order that required a company from this battalion to be sent there. The medium machine guns were split into detachments. Heavy mortars and the two field guns were at Tsangdhar. The former still had no ammunition; the latter had about 400 rounds between them.

The Chinese appear to have used a regiment against the Rajputs.

Some days earlier, a reorganization of sectors put the Nyamjang Chu Valley sector directly under Command Headquarters 4 Division. It was therefore ‘commanding’ widely dispersed sub-units echeloned back from the Namka Chu junction as well as the Hathung La track from Ziminthang. Whatever the Indians tried the Chinese had forestalled them.

Dalvi had correctly forecast D-day but he did not foresee the speed and the strength of the attack. In a telephone conversation earlier, he had told Niranjan Prasad that the Chinese would take about three days to finish his brigade. In the event, they took just that many hours. The shelling, which lasted an hour, was followed by well-coordinated infantry assaults. The telephone lines within the brigade were cut, either by shelling or by Chinese infiltrating groups.

Thus, from the moment the battle began, Dalvi could not communicate with his battalion commanders. Unit radio operators closed down their sets as they had to man the defences when the Chinese began to attack their Headquarters. However, Dalvi was able to maintain radio contact with Divisional Headquarters and 1/9 Gorkha Rifles till about 0800 hours.

| Editor’s Pick |

The senior artillery officer at brigade Headquarters could not get in touch with the guns at Tsangdhar as the Chinese had jammed the radio frequency used by the Gunners. The guns did not fire a single round. The brigade had no layback positions, and no orders on how and where to withdraw.

The Chinese appear to have used a regiment against the Rajputs. They had infiltrated a part of this force between Bridges IV and V on the night of 19/20 October and on the morning of 20 October, struck the Rajputs from the South as well as the North. It is likely that they used another regiment against the Gorkhas and infiltrated a portion of this force under cover of the heavy firing on Tsangle on the night of 18/19 October. On the morning of 20 October, the Chinese appeared all over Tsangdhar; they did not, however, attack Tsangle itself. They used their third regiment on the Khinzemane approach. A part of it seized Hathung La, cutting off the Grenadiers and the Punjabis from Lumpu. A column advancing down the Nyamjang Chu threatened the Headquarters of 4 Division at Ziminthang.

Of the units on the Namka Chu, the Rajputs suffered the most. They lived up to the highest traditions of their regiment, facing overwhelming odds with courage. Their companies were widely dispersed and each fought its own battle, taking on wave after wave of the enemy as long as men remained standing. In many cases, entire platoons were wiped out.

After most of the defended localities had been overrun, the battalion’s Second-in-Command, Major Gurdial Singh, rallied the remnants and led them in a final charge. Most of these men died fighting, or fell wounded; Gurdial Singh was overpowered and captured. The battalion’s command post was the last to be overrun. The commanding officer was taken prisoner after he was wounded.The ferocity of the battle can be judged from the fact that of a total of 513 all ranks on the battalion’s strength that morning 282 were killed; the wounded whom the Chinese captured numbered 81; the unwounded whom the Chinese took prisoner numbered 90. Only 60 of the battalion survived and they were mostly from detachments at Tsangdhar, Lumpu and Towang.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

The Gorkhas on the Northern slopes of Tsangdhar must have felt more secure than the troops on the river. They were, therefore, surprised when they were attacked suddenly from the flanks and later from the rear. They fought back as best as they could but by 0715 hours, the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel (later Major General) Balwant Singh Ahluwalia, ordered a withdrawal to the Tsangdhar Ridge, where the battalion had a company (less a platoon) guarding the dropping zone.

The Chinese were prepared for a very swift victory and were not going to give the adversary any quarter.

In the prevailing conditions, however, the withdrawal was confused, a party making for Rong La. Those who reached the ridge included Ahluwalia, who had been severely wounded. They discovered that the dropping zone was already under attack and took shelter in a hideout below the ridge. Subsequently, this party split up and withdrew through Bhutan by way of Dum Dum La (5,570 metres). Ahluwalia could not accompany his men and was taken prisoner.

The trek through Bhutan was extremely arduous. There were many cases of frostbite and the seriously affected had to be left behind in villages, to be evacuated later on ponies. The battalion’s casualties totalled 226. Of these, 80 had been killed, or were presumed to have died, 44 were wounded and 102 captured. Though outmanoeuvred and outnumbered, the Gorkhas fought well and won several awards for gallantry, including two MVCs.

By 1230 hours, the Chinese had captured the Tsangdhar Ridge. The attack started at 0900 hours from the West, where the Gorkhas had been in position. After overrunning them, they turned to the Gunners. The Para Gunners took on the Chinese with small-arms fire. When the Chinese called out to them to surrender, they took no notice, and fought on until one-third had been killed or wounded and their light machine gun knocked out. The rest were captured.

By 0800 hours Brigade Headquarters had come under small-arms fire. His front and left flank having already collapsed, Dalvi decided to pull back to Tsangdhar, where he hoped to re-form and give battle. He got the necessary permission from Niranjan Prasad and through him informed the Punjabis and the Grenadiers of his decision. Apparently, the kind of campaign that the Chinese had unleashed was beyond the ken of Dalvi and those above him. The Chinese were prepared for a very swift victory and were not going to give the adversary any quarter.

The Indian Army of 1962 had no emergency rations, although during the Second World War officers and troops in all theatres carried this item in their haversacks.

Dalvi, his Headquarters, the Field Company and others who had joined him, left Rong La in two batches. It did not take long for him to realize that the fate of Tsangdhar was sealed and he decided to make for Serkhim, where he hoped to join the Grenadiers. On the following day, Dalvi’s party split up as some of the officers and men could not keep up due to sickness or exhaustion. Without any map to help him, Dalvi lost his way several times. But he and his small band kept going, though they had not had any food since their last meal on 19 October.

The Indian Army of 1962 had no emergency rations, although during the Second World War officers and troops in all theatres carried this item in their haversacks. It was a chocolate-based energy food, packed in a sealed tin, which was meant to last 24 hours. During the First World War and in the Frontier operations, Indian troops had carried parched gram and jaggery as emergency rations. It was humble fare but sustained the men when their normal rations could not reach them. However, during the 1962 compaign many men perished due to starvation and hundreds suffered extreme exhaustion due to the lack of food while trekking through the wilderess of NEFA.

On the morning of 22 October, Dalvi saw a Chinese column moving towards Lumpu. He, therefore, decided to turn East and join the Divisional Headquarters at Ziminthang, not knowing that Niranjan Prasad was at this time trekking back to Towang. Dalvi’s wanderings ended a little later that day when he ran into a company of the Chinese and was taken prisoner along with his companions. The second party from Rong La was more lucky; it reached Darranga on 31 October. A reception camp had been set up at this place, near the Bhutan border.

The Punjabis had not been shelled on the morning of 20 October. Around 1100 hours, Niranjan Prasad ordered them to pull back to Hathung La. However, when the withdrawal began, the Chinese brought down mortar and small-arms fire on their position and followed up with an assault. Heavy fighting ensued but the Punjabis managed to break contact and withdraw. The Chinese had, however, reached Hathung La before the Punjabis could get there. Lumpu, their next choice, was also found to be in enemy hands. The battalion, therefore, withdrew through Bhutan, its company at Tsangle also taking the same route.

| Editor’s Pick |

During the actions on 10 and 20 October, the Punjabis fought with great skill and courage, many of the officers and men winning awards for gallantry. These included three MVC.

The Grenadiers’ company at Drokung Samba was attacked by a Chinese battalion on the morning of 20 October. The enemy had blown up the bridge on the Nyamjang Chu. With the bridge gone, there was no prospect of this company joining their battalion and, under their young commander, Second lieutenant G.V.P. Rao, they fought with their backs to the wall. He and a score of his men were killed, many more were wounded or captured but a few managed to reach Ziminthang.

The main body of the Grenadiers had received the withdrawal order at the same time as the Punjabis. Like them, they withdrew through Bhutan.

This was the end of 7 Brigade. Within hours, the Chinese had smashed it into bits and pieces. The only formed body of this once-famous brigade that was visible on 20 October was the long line of prisoners being led into captivity across Thag La. But let it be said: no man flinched or ran. As an organized formation 7 Brigade ceased to exist by 1200 hours on 20 October, but this cannot be placed on the head of the individual fighting man. There were simply too many negatives working against it.

Without any map to help him, Dalvi lost his way several times. But he and his small band kept going, though they had not had any food since their last meal on 19 October.

The tactical Headquarters of 4 Division withdrew from Ziminthang on the morning of 21 October when it was closely threatened. A company of 4 Garhwal Rifles, which was covering this Headquarters, also fell back. While Niranjan Prasad was trekking back to Towang, he received a message appointing him corps commander in officiating capacity. Had he been given the appointment four days earlier, he might have authorized 7 Brigade to move to more defensible positions.

Having reached the Serkhim-Lumpu area, the Chinese commander sent the main body of his troops on to Towang, keeping some behind to clear the captured areas. By the morning of 23 October, the Chinese reached Lum La, South-West of Towang. In the early hours of that morning, they launched their main attack against Towang from the North, bringing up a fresh division for the task.

Even the swift rout of 7 Brigade did not bring home to those in authority the gravity of the situation, and they merely contented themselves by issuing text-book appreciations and orders, the kind practised during annual manoeuvres. An instance of this was a report that 4 Corps sent around 2300 hours on 20 October to Eastern Command and Army Headquarters. The report said that the Corps’ intention was to keep the enemy out of heavy mortar range of the dropping zone at Lumpu. Then, during the night of 21/22 October, the same Headquarters sent an order to 4 Division Artillery Brigade to occupy a compact and mutually supporting defended sector for the defence of Towang, as though the Chinese, advancing with two divisions would wait while the meagre garrison of this monastery town got ready for battle. Had a realistic appraisal of the situation been made and a bold decision taken to withdraw quickly to Bomdi La, the heavy losses that the Indian Army suffered at Towang and Se La would have been avoided. The loss was the greater in self-esteem, morale and a complete lack of confidence in the higher commanders.

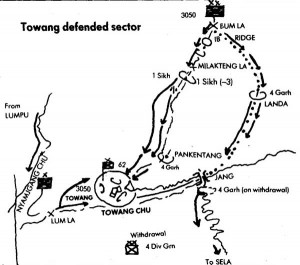

I have earlier noted the last-minute efforts to reinforce NEFA. Kaul had asked for 11 Infantry Brigade, but Sen could not pull out this formation as it was committed around Manipur in a counter-insurgency role. He, however, told Kaul to make use of the Headquarters of 62 Infantry Brigade, which had been kicking its heels since its arrival from Ramgarh. He would give him the infantry element for it as battalions became available. The first unit to join 62 Brigade was 13 Dogra (from 11 Brigade). Two companies of the battalion arrived at Towang on the night of 21 October together with the Brigade Headquarters.Of the infantry units already at Towang, 1 Sikh held the forward-most positions on the Bum La approach. One of its platoons was on the IB Ridge, two kilometres South of the border; the Battalion Headquarters was at Milakteng La together with one company, while the remaining companies held features dominating the tracks that led to Towang. 4 Garhwal Rifles, which had arrived a fortnight earlier, had its Headquarters and one company at Towang, another company at Landa, on the track that led from Bum La to Jang and the third company at Pankentang, North of Towang (see Fig).

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

The eight guns of 97 Field Battery were a short distance from Towang, at a spot where the road in the direction of Bum La ended. The two mountain batteries – 7 (Bengal) and 2 (Derajat) – were deployed in support of the two infantry battalions; a troop of heavy mortars was in position West of Milakteng La. Detachments of the Assam Rifles held border posts, including the one at Bum La. This pass was out of range of Indian artillery, as positioned. Soon after their arrival, therefore, the two companies of the Dogras had been sent out to hold the Western approach to Towang.

The Chinese made a three-pronged advance on Towang from the North. One of their columns came down the Bum La- Tongpeng La route. Another went South-East in the direction of Jang. The third prong consisted of a part of their Khinzemane column; it advanced by way of Samatso. The column advancing on Tongpeng La overran the Assam Rifles’ post at Bum La around 0430 hours on 23 October. Soon after, the Sikhs’ platoon on the IB Ridge came under attack from a company of the enemy. The platoon commander was a doughty JCO, Subedar Joginder Singh, a veteran of the Second World War. He was ready for the Chinese and his platoon mowed down a good number from the first wave.Half an hour later came a second attack. Again, the Sikhs held their ground. Joginder Singh was wounded but retained command. At 0600 hours a third attack came. By then, casualties had reduced his platoon to half. Joginder Singh himself took up a light machine gun but the Chinese kept advancing despite heavy losses. In desperation, this dauntless Sikh ordered his men to fix bayonets and charged the oncoming enemy, killing many. Only four men of this platoon later managed to reach their main company position. Joginder Singh was taken prisoner and died of his wounds in captivity. His gallantry was of the highest order and the Government recognized it with an award of the PVC.

The decision to evacuate Towang was taken by Sen. He had arrived there the previous day (22 October) and the orders and counter-orders that he issued “˜turned the fluid situation then prevailing into utter confusion.

By 0730 hours, the Chinese reached 1 Sikh company’s delaying position at Tongpeng La. Here, too, the Sikhs fought with determination against heavy odds. They held the position till 1100 hours, when they received orders to pull out. Bengal Mountain Battery gave good support to the Sikhs at this position. The field guns of 97 Field Battery engaged Chinese concentrations within their reach, each piece firing off about 300 rounds per gun.

The decision to evacuate Towang was taken by Sen. He had arrived there the previous day (22 October) and the orders and counter-orders that he issued ‘turned the fluid situation then prevailing into utter confusion’. First he ordered that Towang would be held at all costs; he was going to induct two more brigades to reinforce the garrison, he gave out. He stayed that night at Towang and met Niranjan Prasad, who got there around 1800 hours from Ziminthang, making good time. However, the swift Chinese advance on the morning of 23 October made him change his mind. The Chinese column advancing on the Landa-Jang axis had brought the Garhwal Company on that route under heavy fire. The enemy was evidently making a bid to cut off 4 Division by capturing the bridge over the Towang Chu at Jang.

Sen’s orders, which he issued before flying back from Towang, were that the forward troops should break contact; thereafter they, together with the garrison in Towang, should fall laterally back on Jang. In case Jang was already in enemy hands, the troops were to make for Bomdi La, where he intended to position 65 Infantry Brigade. This formation, under Brigadier Sayeed, was then on the move from Secunderabad.

These orders were, however, changed that night. The changed orders, issued by 4 Corps, required 62 Brigade to hold Se La with 1 Sikh and 4 Sikh LI. The latter, from 48 Infantry Brigade, was being flown from Punjab. Jang was to be held by Headquarters 4 Artillery Brigade with some troops which were already there and 4 Garhwal Rifles. The decision to hold Se La had a profound effect on the campaign.

| Editor’s Pick |

Holding Se La was tempting in many ways. ‘Holding it would mean loss of less territory; an important consideration politically. . . ’. Many people thought Se La was impregnable due to its height, 4,180 metres. There was a steep climb to the pass from the Towang Chu Valley and the road was dominated by the pass and the peaks on its flanks. All these factors made Se La a strong position. But it was not impregnable and there were tracks that by passed it. The Chinese were not road-bound like the Indian Army and could isolate Se La. They had already proved that their speed of movement in organized fighting bodies upto regimental strength was remarkable. The main disadvantage of holding it, except as a delaying position, was its distance from Indian bases. Its very height was another disadvantage; its garrison would have to operate at high altitudes. Also, the long line of communication from Bomdi La would need protection. In the event, the Chinese succeeded in cutting the road before they attacked Se La itself. The decision to hold Se La has been attributed to a visit by Thapar to Headquarters 4 Corps on 23 October. He was accompanied by Palit, his Director of Military Operations.

“˜Chinese expectations that defeat would soften Indias attitude to the border question were belied by the reaction in India.

Towang had not been prepared for evacuation. The precipitate withdrawal created chaos. ‘Streaming down with the troops were pioneers, Assam Rifles personnel and hundreds of civilians, including lamas from the monastery’. The task of covering the withdrawal had been given to 4 Garhwal; thereafter, the battalion was to hold Jang, together with the Engineers already there. The battalion had only two jeeps in the way of transport, which meant marching manpack and destroying all that could not be so carried. The Sikhs too lost a good deal of equipment during the withdrawal. The Artillery were the worst sufferers; every field gun and mortar had to be abandoned. Sizeable stocks of supplies, clothing and ammunition had been built up at Towang during the preceding weeks. Most of these fell into Chinese hands.

By 24 October, the tactical Headquarters of 4 Division had been set up at Dirang Dzong, 64 kilometres South-East of Se La. 4 Garhwal had deployed one company on the bridge at Jang and the rest of the battalion (less a company) was occupying positions on the Jang-Se La axis. Towards evening, when the Chinese began to engage the Garhwalis holding the bridge, it was blown up and the battalion withdrew to occupy a screen position before Se La.

Important changes in command took place on 24 October. Lieutenant General Harbakhsh Singh took over 4 Corps and Niranjan Prasad was replaced by Major General A.S. Pathania. A well-decorated soldier, Pathania had won the Military Cross in the Second World War and the MVC after Independence. Before taking over 4 Division he had been the Director General of the National Cadet Corps.

A lull descended over NEFA after the Chinese occupied Towang. They needed a pause before embarking on the second phase of their operations. They had to improve their lines of communication, build up supply bases and regroup their force. They decided to use the pause for diplomatic overtures. On 24 October, while the dust of battle was still settling down over Towang, the Chinese Premier wrote to Nehru, suggesting a meeting. But the basis that he proposed was a formula that had been rejected by India earlier. Nehru turned down the proposal.

‘Chinese expectations that defeat would soften India’s attitude to the border question were belied by the reaction in India. After the initial shock wore off, Nehru found the whole country lined up solidly behind him, resolved to fight the invader’. The invasion had brought a new sense of unity among the people. Chinese efforts to follow up with an explanation of their proposals failed to impress India, though these had some propaganda value in international circles.Menon could not, however, escape severe criticism for the unpreparedness of the Army. Reluctantly, Nehru relieved him, and himself took over the Defence portfolio.19 The need of the moment forced him to ask friendly nations for military aid. The first loads of arms aid arrived from the United Kingdom. Early in November, American planes began to arrive in Calcutta with semi-automatic rifles, radio sets, mortars, recoilless guns and other items. Canada, France, Australia, New Zealand and many other countries also responded generously.

‘Chinese expectations that defeat would soften India’s attitude to the border question were belied by the reaction in India. After the initial shock wore off, Nehru found the whole country lined up solidly behind him, resolved to fight the invader’. The invasion had brought a new sense of unity among the people. Chinese efforts to follow up with an explanation of their proposals failed to impress India, though these had some propaganda value in international circles.Menon could not, however, escape severe criticism for the unpreparedness of the Army. Reluctantly, Nehru relieved him, and himself took over the Defence portfolio.19 The need of the moment forced him to ask friendly nations for military aid. The first loads of arms aid arrived from the United Kingdom. Early in November, American planes began to arrive in Calcutta with semi-automatic rifles, radio sets, mortars, recoilless guns and other items. Canada, France, Australia, New Zealand and many other countries also responded generously.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

During the interlude, Kaul decided to return to 4 Corps; Harbakhsh Singh left exactly five days after he had taken over. Kaul had not yet fully recovered from his sickness but returned as staying back ‘would smack of either a punishment or evasive action’.20 After assuming command of 4 Division, Pathania made an estimate of his requirements for defending the Se La-Dirang Dzong-Bomdi La area and informed 4 Corps that he needed 17 Infantry battalions for the task.

Kauls request for new airfields and foreign aircraft with pilots was unrealistic. Other nation could not be expected to rush their air forces to India unless she had a prior arrangement or treaty for such aid.

For his part, Kaul asked for two more infantry divisions. To boost his logistics support, he suggested that friendly countries should be requested to provide aircraft with pilots and maintenance facilities. He also suggested the widening of the existing airfields and construction of new ones.

Kaul’s request for new airfields and foreign aircraft with pilots was unrealistic. Other nation could not be expected to rush their air forces to India unless she had a prior arrangement or treaty for such aid. In any case, the Chinese did not give India much time before commencing the second phase of the invasion. It must, however, be mentioned that at the time a belief had grown that the Chinese were not likely to continue their offensive in NEFA. One of the reasons adduced was that they were already well beyond the disputed Thag La region. Apparently, the Chinese maps which showed the boundary at the foothills of NEFA were forgotten. Another reason put forward was that they would not be able to complete the Bum La—Towang road before the winter set in. These may be some of the reasons for the slow build-up of 4 Corps during the lull.

Slowly, new units began to arrive in the theatre. They did not come properly equipped. Coming from various parts of India, they did not even bring their first-line transport. Except for pouch ammunition and personal arms, they hardly brought anything else. There was an extreme paucity of defence stores and digging tools; without them effective defence was not possible. The airlift made available to 4 Division was 50 tons a day against a requirement of 250 tons.

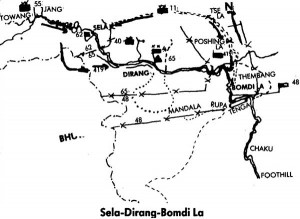

By the second week of November, 62 Brigade had established itself at Se La (see Fig.). It now had five infantry battalions under command. Three of them – 1 Sikh, 2 Sikh LI and 4 Sikh LI – were holding positions on Se La or features around the pass. The Garhwalis still held the screen position North-West of Se La which they had occupied after evacuating Jang.

Brigade Headquarters was South of Se La and the fifth battalion – 13 Dogra – was at Senge, further South, guarding the dropping zone. The brigade’s artillery element comprised three batteries of field guns (two from 5 Field Regiment, one from 6 Field Regiment), 2 (Derajat) Mountain Battery, 116 Heavy Mortar Battery and a troop of 34 Heavy Mortar Battery. Located near the Brigade Headquarters was 19 Field Company and 2 Sikh LI had a platoon of Mahar machine-gunners under command.The Headquarters of 65 Brigade was at Ewang, a short distance North of Headquarters 4 Division at Dirang Dzong. Of its two infantry battalions, 19 Maratha LI was deployed in and around Ewang and 4 Rajput was holding a bridge on the Senge-Dirang Dzong road with other companies widely dispersed. The artillery with the brigade consisted of the Headquarters of 6 Field Regiment, one of its batteries and a section of mountain guns. A platoon of 7 Mahar (machine guns) was also under the brigade.

Straightaway after the fall of Towang, they began work on it and before the second week of November was out, the road was more or less ready.

At Bomdi La, 48 Brigade was in position with three infantry battalions 5 Guards, 1 Sikh LI, 1 Madras. Besides a platoon of 7 Mahar machine-gunners, it had a battery from 6 Field Regiment, one mountain battery and two tanks from 7 Light Cavalry. This armoured regiment (less a Squadron) had moved from Varanasi in the last week of October. On arrival at Misamari it was ordered to send forward one squadron. of this squadron, one troop was to be deployed at Bomdi La, another (with Squadron Headquarters) at Dirang Dzong, and the third at Se La. Due to the bad road conditions and the steep climbs, the squadron made Bomdi La only on 5 November after losing two tanks and some men on the way. When the remaining tanks arrived at Dirang Dzong, it was discovered that the climb to Se La was beyond their capacity.

As they settled down in their new positions, the troops undertook a certain amount of aggressive patrolling. Morale was gradually building up. A party of Press reporters visited Se La in the second week of November and brought back a good impression of the troops. There was an air of optimism at the front and in the rest of the country. It was felt that the worst was over. The belief in the invincibility of Se La was reflected in the new name given to the operational plan: ‘Olympus’. A consignment of 7.62 semi-automatic rifles and 81-mm mortars had been received by 4 Division. These weapons were, however, not put into the hands of troops; possibly, their ammunition had not arrived. Most of the crates containing the new weapons later fell into Chinese hands, unopened.

The Chinese had catered for the building of the Bum La—Towang road before they began their second phase. Straightaway after the fall of Towang, they began work on it and before the second week of November was out, the road was more or less ready. Thereafter, they began to improve the Towang-Jang section; by the morning of 17 November, the bridge at Jang was in commission and the infiltration began.21

| Editor’s Pick |

In an appreciation, Kaul had vaguely referred to the likelihood of enveloping moves from the East and West of the main axis to outflank Se La. However, he took no steps to meet such a contingency. The Bomdi La-Se La sector had ten infantry battalions against the 17 which Pathania had asked for. But even with these meagre resources it should have been possible to form a mobile reserve. Kaul and Pathania, however, contented themselves with static defence, with many of the battalions being split up into companies to hold isolated hilltops.

Like the Japanese in Burma, the Chinese chose a very difficult route to outflank 4 Division from the East. They used the Bailey Trail. In 1913, Captain F.M. Bailey had accompanied the Survey team whose findings enabled McMahon to draw the boundary between India and Tibet, East of Bhutan. On their return journey from Tibet, Bailey and his party used the Tulung La-Tse La22-Poshing La-Thembang route. In his report, Bailey had described parts of the route as very bad. It was assumed by Pathania that it would not be possible for the Chinese to bring up a sizeable force using the Bailey Trail; a company was the maximum they could bring, he thought. In this assumption he was supported by Army Headquarters and the Intelligence Bureau. The lessons of the Burma Campaign were forgotten, as also the fact that nothing is too difficult for determined troops. In the event, the Chinese brought up about 1,500 of their troops by this route.

The Se La defences were outflanked from the West also by a sub-detachment of a special grouping called 419 detachment. The conventional break-in at Se La was delivered by 54 Division followed up by 11 Division of the Chinese. This frontal assault combined with the cutting of 4 Division’s lines of communication North-West of Dirang Dzong and Bomdi La and posing a threat to the denuded Bomdi La brigade defended sector completely unhinged the defences echeloned linearly along the lines of communication.

The Assam Rifles had a platoon post at Poshing La (4,170 metres). On 6 November, Pathania sent a platoon from 5 Guards (ex 48 Brigade) to reinforce it. On the third night out, the porters and ponies accompanying the platoon deserted. This was possibly the work of Chinese agents. Captain Amarjit Singh, who was in command of the platoon, sent a radio signal to his battalion for replacements.Meanwhile, patrols from units at Se La and beyond had reported that the Chinese were sending large numbers of troops towards Poshing La in small parties, using tracks North of the Towang Chu and the Mago Chu. Some of the patrols had even clashed with the Chinese. At first the divisional Headquarters refused to believe these reports but when they persisted, Pathania ordered 48 Brigade on 11 November to get 5 Guards to build up the post at Poshing La to a company.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

Amarjit Singh established his platoon at Poshing La by 13 November. On the following day, he set out with 22 of his men to reconnoitre the route beyond. Around 0900 hours on 15 November, his party was ambushed. Amarjit Singh and his men fought gallantly but were overwhelmed by superior numbers. He was killed, and only four men from this party came back.

The presence of the enemy on the Dirang Dzong-Bomdi La road caused shock and dismay at Pathanias Headquarters.

Poshing La was attacked that afternoon. By then, the resupply column sent by 5 Guards had reached the post. The Guardsmen fought back for an hour; thereafter, the remnants fell back on Chhang La. The Chinese followed close on their heels and drove them further South to Lagam, where they joined the Headquarters of their company and two platoons which had been despatched from Bomdi La. The Guardsmen thereafter tried to hold a hill North of Lagam but the attempt proved futile. The Chinese were already there.

When a report of the ambush of Amarjit Singh’s party reached divisional Headquarters, Pathania ordered another company from 5 Guards to proceed to Poshing La. This company could leave Bomdi La only on the morning of 16 November. When it had moved about nine kilometres, Brigadier Gurbux Singh, Commander 48 Brigade, came up and ordered it to establish a firm base for its battalion at Thembang. Pathania had by then ordered that the remainder of 5 Guards should move there. The mission given to the battalion was to retake Poshing La.

The Guards arrived at Thembang on the morning of 17 November; by the afternoon, they had established themselves on the high ground East of the village. The Chinese were not far away. They soon brought the battalion under mortar and machine-gun fire. The Guards’ mortars opened up in answer but the mountain guns supporting them could not fire as the radio set with the forward observation officer refused to work. Soon after, about 500 of the enemy were seen forming up for attack. The Guards’ mortars took them on but the Chinese began to rush across regardless of casualties. Thereafter came probes against the Guards’ flanks. At the same time, a large concentration of the Chinese was seen in a nulla South of the village.

Extensive patrolling had been undertaken to build up morale and to reconnoitre the likely approach routes of the enemy.

The coup de grace was delivered by a force that was estimated at about 1,500. The Guards fixed bayonets and took a heavy toll of the enemy. However, their mortar and light machine-gun ammunition having almost finished, they could not hope to hold the position much longer. The brigade commander authorized a withdrawal but, in the ensuing nightfall the battalion disintegrated. The Chinese suffered an estimated three to four hundred casualties in this action. The Guards’ casualties totalled 162, including 95 missing.

By the time the Guards began their withdrawal from Thembang, the Chinese had cut the Dirang Dzong road about nine kilometres North of Bomdi La; the rest of 5 Guards reached the Tenga Valley and Charduar in small parties.

The presence of the enemy on the Dirang Dzong-Bomdi La road caused shock and dismay at Pathania’s Headquarters. The Walong defences had crumbled on 16 November and Kaul had spent most of that day flying over various parts of the sector, organizing a new defence line. That night he sent a long radio signal on the situation to Eastern Command and Army Headquarters. In this communication, he urged that in strength as well as equipment, the Government should get such armed forces from outside as were willing to come to India’s aid. The idea of getting help from foreign armies had been in Kaul’s mind for some time. While he was in Delhi during his sickness, he had given to Khera, the Cabinet Secretary, a paper recommending that India should seek such assistance.23

| Editor’s Pick |

Kaul spent most of 17 November also in the Lohit sector, looking for the survivors from Walong, arranging food for them and organizing a new defence line. By the time he turned his attention to 4 Division, the situation was already beyond control. In the night, he ordered 48 Brigade to send a mobile column of two infantry companies and two tanks to open the Dirang Dzong road. This order was cancelled after an hour or so when it was explained to him that 48 Brigade now had only six infantry companies at Bomdi La. Of the two battalions there, one company of 1 Sikh LI was on detached duty at Phutang to cover the Western flank of 48 Brigade. A company from the other battalion — 1 Madras — had gone to Dirang Dzong the previous night on Pathania’s orders. He wanted to reinforce the troops guarding his Headquarters.

The next day Bomdi La itself came under attack. Before recounting this attack however, let us take a look at the happenings at Se La and in the Dirang Valley.

Brigadier Hoshiar Singh was in command of 62 Brigade at Se La. He had come over from the National Defence Academy and taken over on 29 October. Hoshiar Singh was a soldier with combat experience. He had won the Indian Distinguished Service Medal, the Indian Order of Merit and the Croix de Guerre. He had commanded a battalion of the Rajputana Rifles and knew how to inspire confidence in his men. Though there were large shortages of equipment in 62 Brigade, he had managed to establish it fairly well. Extensive patrolling had been undertaken to build up morale and to reconnoitre the likely approach routes of the enemy. The Chinese too had been probing the brigade’s defences.

The Chinese threw in more and more men and, after fierce fighting, were able to gain some ground.

The most serious patrol encounter took place in the early hours of 16 November. The previous day, Hoshiar Singh had sent a three-company-strong fighting patrol to reconnoitre the area North-East of Se La. Its two forward companies, from 2 Sikh LI, were surrounded in their night harbour and lost one officer and 60 men killed and missing. Another ominous happening of 16 November was the sighting of a Chinese column, about a thousand-strong, moving South along the India-Bhutan border. Two companies of 4 Sikh LI, deployed in the Twin-Lakes area North-West of Se La, observed the movement and all guns of 5 Field Regiment engaged the column. But it soon disappeared into a nulla and was lost to view. This meant that Se La had been bypassed on both flanks.

The Chinese launched their attack on Se La from the North around 0500 hours on 17 November. Their advance guard was led by men in Monpa dress.24 The Garhwalis holding the screen position fought back valiantly. They were able to blunt three enemy attacks and inflict heavy casualties. However, the Chinese threw in more and more men and, after fierce fighting, were able to gain some ground. By 1600 hours the battalion’s telephone line was cut and it was also out of radio contact with Brigade Headquarters.

Around 1700 hours, Hoshiar Singh sent two liaison officers to the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel B.M. Bhattacharjea; they carried orders for the withdrawal of the battalion during the night. Two of its companies were to be deployed in the Brigade Headquarters area and the rest of the battalion was to take up positions on the pass so as to give more depth to the defences held by 1 Sikh. At the same time, the two companies of 4 Sikh LI in the Twin-Lakes area were ordered to withdraw to the main Se La positions.

Hoshiar Singh’s intention was to hold Se La as a fortress. He had enough supplies for a week. Unfortunately, he received no support from Pathania and the withdrawal from Se La, which took place later, was the sorriest episode of the 1962 debacle.

Pathania’s first reaction to the road-block on the Bomdi La-Dirang Dzong road was to ring up and tell 62 Brigade to withdraw to Dirang Dzong. Hoshiar Singh protested that he was prepared to remain at Se La and fight provided he was assured of air supply. This happened around 1700 hours on 17 November. A little later, Pathania rang up again. He told the brigade commander that air supply could not be guaranteed and that he must withdraw that night. His plan for 62 Brigade was that it should join 65 Brigade and Divisional Headquarters, after which the combined force would fight its way to Bomdi La. Hoshiar Singh explained that a withdrawal that night would cause panic and that the earliest he could pull out was on the following night. Pathania approved the latter course. He was however worried about the security of his own Headquarters and told Hoshiar Singh to send two companies of infantry to Dirang Dzong quickly. The task fell to 13 Dogra.

Pathania had been in touch with 4 Corps to get approval for abandoning Se La. Kaul had not yet returned from the Lohit sector and when Pathania rang up Brigadier K.K. Singh, the latter asked him to speak to Sen. The reverse at Walong had brought Thapar as well as Sen to Tezpur but both refused to take a decision. Pathania was told to wait for the corps commander’s return. Both were fully in the picture regarding the situation and the proper course would have been for them to take a decision and convey it to Pathania straightaway. But they chose to shirk responsibility.

Pathania had been in touch with 4 Corps to get approval for abandoning Se La. Kaul had not yet returned from the Lohit sector and when Pathania rang up Brigadier K.K. Singh, the latter asked him to speak to Sen. The reverse at Walong had brought Thapar as well as Sen to Tezpur but both refused to take a decision. Pathania was told to wait for the corps commander’s return. Both were fully in the picture regarding the situation and the proper course would have been for them to take a decision and convey it to Pathania straightaway. But they chose to shirk responsibility.