The Chinese reaction to the setting up of a post by India at Che Dong was a calculated move. By this time, China appears to have decided on a full-scale campaign to assert her territorial claims. According to independent observers, the Chinese would have sought provocations elsewhere if no trouble had taken place at Che Dong.l Brigadier J.P. Dalvi, who was taken prisoner during the hostilities, also arrives at the same conclusion. While he was in their custody, he saw the elaborate arrangements that the Chinese had made for 3,000 prisoners.

Che Dong was no prominent landmark, or a feature of tactical importance. It was merely a cluster of herders’ huts built by Monpa tribesmen of the region. The huts lay a short distance from the spot where the boundaries of India, Bhutan and Tibet meet. In fact 33 Corps had ordered that the post should be set up at the trijunction itself. However, the Assam Rifles’ detachment that went to establish it found the site unsuitable owing to its altitude and inaccessibility and selected Che Dong instead. The place lay on the lower slopes of a range called Tsangdhar, which runs Eastwards from the knot of mountains that form the trijunction. The post faced the Thag La Ridge. Between Thag La and Tsangdhar is a mountain stream, called the Namka Chu, which flows from West to East.

Click to buy: Indian Army After Independence

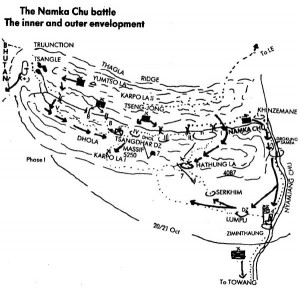

Here, a word about the Namka Chu. Its source lay North-West of Che Dong among a group of lakes near Tsangle, at an altitude of 4,590 metres. About 26 kilometres in length and 6 to 16 metres in width, it ran in a deep, boulder-strewn bed with banks six to ten metres high. By the time it joined the Nyamjang Chu near Khinzemane, it dropped some 2,620 metres. Though fast-flowing, it was fordable, except during and immediately after the monsoon and when the snows melted. The river valley was thickly wooded; movement was difficult, except on the tracks, and fields of fire were limited.

How did Thag La come to be treated as Indian territory when it was shown North of the McMahon Line on the Survey of India maps? The answer is to be found in the Simla Convention of 1914.

Local herders had thrown wooden bridges across the Namka Chu for use when it was unfordable. These consisted merely of logs tied together and slung across the stream. There were five of these bridges and they came to be numbered from East to West as I, II, III, IV and V. Following the Hathung La route to Dhola Post, the track hit Bridge I. Across it, the track forked. Going Eastwards one reached Khinzemane; going North-West along the river and recrossing to the South at Bridge II, one reached Dhola Post opposite Bridge III. A short distance from the post was Bridge IV, and close to Tsangle was Bridge V. Between Bridges IV and V were two more bridges: Temporary Bridge and Log Bridge. The bridges, of no use to man or beast when the river was not in spate, became vital points to be defended to the utmost. In October one could walk across the river without using the bridges.

Thag La is higher than Tsangdhar and runs almost parallel to it. Thus, the Che Dong Post was overlooked by Thag La as also the Tsangdhar range itself. Sited thus, it served no purpose. In case the Army wanted to set up a post in the region, it should have been sited either upon Thag La or atop Tsangdhar.

The Assam Rifles were responsible for setting up border posts. However, as the latter were under the Army’s operational control, it helped in their establishment. While this particular post was being set up, the officer entrusted with the task was questioned over the radio by the General Officer Commanding 4 Infantry Division, Major General Niranjan Prasad, as to why a site shown North of the McMahon Line on the map was selected. In reply he was told that according to the Intelligence Bureau representative with the party, even the Thag La Ridge was Indian territory. In most contemporary records, the post is incorrectly mentioned as the Dhola Post. The Dhola feature, in fact, lay a few kilometres South of the McMahon Line but the man on the spot somehow gave this name to the post at Che Dong and it stuck.

Prasad was unhappy about this post. From the middle of July 1962, he made several representations to the effect that it should either be withdrawn or moved forward to a tactically sound position on the Thag La Ridge, in case that ridge was Indian territory. His objections were conveyed to higher authorities, right up to Army Headquarters and the Defence Ministry but no reply was received till 12 September, when he was told that Thag La was indeed Indian territory and the Army must exercise the country’s rights over it. The decision came too late; by then, the Chinese were already on Thag La in strength, with regular People’s Liberation Army first-line troops.

| Editor’s Pick |

How did Thag La come to be treated as Indian territory when it was shown North of the McMahon Line on the Survey of India maps? The answer is to be found in the Simla Convention of 1914. At this Convention, Sir Henry McMahon had generally taken the Himalayan watershed as the frontier. In fact, one of the objectives of the Indian Government at this convention was to secure a strategic watershed boundary between the two countries. Where the boundary terminated in the West, ‘there was no watershed to be followed, and McMahon drew his line along what his maps showed as outstanding ridge features’.2 However, after Independence when the Indian authorities began to take a closer look at the country’s Northern borders, it was found that on transposing the McMahon Line to the ground from its map coordinates, the line would not run along the highest ridge in the area. The Thag La Ridge, lying four to five kilometres North of the map-marked McMahon Line, was the highest feature and India decided to treat the crest of this ridge as the boundary.

The Army authorities, from Army Headquarters down to brigade Headquarters, were apparently guided by this decision when the post at Che Dong was set up. Had they known that Thag La was Indian territory, the story of the 1962 hostilities might have been different.

The Indian Government thus knew of the Chinese stand on Thag La and it might have been more expedient to let sleeping dogs lie than to set up a post at Che Dong

As it was, Thag La was important for the Chinese too. On its Northern slopes was Le, a large Tibetan village, which was the obvious site for a Chinese forward base for any operations against India in this sector. Besides, there had been trouble over the ridge earlier.

In August 1959, the Assam Rifles set up a checkpost at Khinzemane, on the South-Eastern tip of the Thag La Ridge where the Namka Chu joins the Nyamjang Chu, a river that flows from Tibet into NEFA. The Chinese reacted sharply. About 200 of them appeared on the scene and pushed the Assam Rifles’ men to the bridge on the Nyamjang Chu at Drokung Samba, a few kilometres to the South which they claimed was the boundary according to the McMahon Line. Thereafter, the Chinese withdrew. A couple of days later, the Assam Rifles returned to Khinzemane. The Chinese again tried to push them out but this time the Assam Rifles made it clear that they would resist. The Chinese made no further attempt to remove the Khinzemane post but protest notes began to fly between the two Governments. A stalemate followed after India proposed discussions on the exact alignment of the boundary at Khinzemane and other disputed points.

The Indian Government thus knew of the Chinese stand on Thag La and it might have been more expedient to let sleeping dogs lie than to set up a post at Che Dong, a place that was nothing but a death-trap for the men guarding it.

Let us now take a look at the military situation in the sector as on 9 September 1962, the day Defence Minister Krishna Menon ordered the eviction of the Chinese facing the Assam Rifles’ post at Che Dong.

It was almost three years since 4 Division had been made responsible for the defence of NEFA. During this period, there had been no increase in the strength of the division or in its striking capacity. The Divisional Headquarters was still at Tezpur and the Headquarters of 7 Brigade was at Towang. Major General Niranjan Prasad had taken over command of the division in May 1962. Brigadier John Parashram Dalvi had assumed command of 7 Brigade a few months earlier. He had just finished a stint at 15 Corps Headquarters as Brigadier-in-Charge Administration. Earlier, he had commanded a Guards’ battalion.

The Border Roads Organization, set up in 1960, made commendable efforts after they took over the task of road-building in this sector. But it was impossible for this organization to complete in two years a task that would normally take twelve. By September 1962, a one-ton road was built upto Towang. As it had to be laid across the grain of the Southern Himalayas, it would take many years to settle down and was at the time only fit as a fair-weather road. Monsoon rains had damaged it extensively, large chunks having been washed away.Taking a look at the terrain that this road traverses, one becomes aware of the tremendous difficulties the Army engineers faced in building it. From the foothills of the Himalayas, Nordi of Misamari, it climbs 2,743 metres above sea-level to reach a place called Eagle’s Nest; a further climb of about 200 metres takes one to Bomdi La. Thereafter, there is a drop to Dirang Dzong, situated at 1,676 metres. Then begins the ascent to Se La, perched at 4,180 metres followed by a steep drop to Jang (1,524 metres), and finally the climb to Towang (3,048 metres).

The Border Roads Organization, set up in 1960, made commendable efforts after they took over the task of road-building in this sector. But it was impossible for this organization to complete in two years a task that would normally take twelve. By September 1962, a one-ton road was built upto Towang. As it had to be laid across the grain of the Southern Himalayas, it would take many years to settle down and was at the time only fit as a fair-weather road. Monsoon rains had damaged it extensively, large chunks having been washed away.Taking a look at the terrain that this road traverses, one becomes aware of the tremendous difficulties the Army engineers faced in building it. From the foothills of the Himalayas, Nordi of Misamari, it climbs 2,743 metres above sea-level to reach a place called Eagle’s Nest; a further climb of about 200 metres takes one to Bomdi La. Thereafter, there is a drop to Dirang Dzong, situated at 1,676 metres. Then begins the ascent to Se La, perched at 4,180 metres followed by a steep drop to Jang (1,524 metres), and finally the climb to Towang (3,048 metres).

The total distance from the foothills is only about 291 kilometres but it takes several days to cover. Considering the necessity for acclimatization of troops inducted from the plains, quick reinforcement of the theatre was impracticable. Also, till then, no staging facilities had been provided on the route and there were no replenishment dumps. In fact, a journey to Towang was a nightmare.

Considering that the McMahon Line in Kameng stretched for about 150 kilometres, this solitary brigade was woefully inadequate for these tasks.

Beyond Towang, ponies, mules and porters were the only mode of transport. Two main routes led from here into Tibet. One led North, by way of Pankentang, Tongpeng La and Bum La to Tsona Dzong. Its subsidiary also reached Bum La direct from Jang, bypassing Towang. The other route followed the Nyamjang Chu most of the way. Lum La, about 35 kilometres West of Towang, was the first important valley to reach Shakti, another 28 kilometres upstream. Keeping along the river for another 36 kilometres, one reached Khinzemane. From there a track over the Thag La Ridge led to Le.

To reach the Assam Rifles’ post at Che Dong, one had to leave the Shakti-Khinzemane route about 5 kilometres short of the point where the Namka Chu meets the Nyamjang Chu, go West to Lumpu (3,048 metres), whence a path led North across Hathung La (4,396 metres) to Che Dong (see Fig. 9.1). The last leg of this route ran along the North bank of the Namka Chu, right under the Chinese positions on Thag La. Indian troops had, therefore, to use an alternative route later on. This was longer and more difficult. It led Westward from Lumpu by way of Karpo La I (5,250 metres,) on to the Tsangdhar range and thereafter descended steeply to the Namka Chu. From the Tsangdhar Northern face another faint track of sorts led towards the trijunction.

Besides the main routes mentioned above, there were several tracks in India and Tibet that joined them either laterally or longitudinally at different points over little known passes and alignments. Also, there were many footpaths in the region that traversed the India-Bhutan boundary. For the Chinese, access to the Namka Chu Valley was comparatively easy. From Thag La, their forward base at Le was only a three-hour march away. During their offensive, they extended their motor road from Tsona Dzong to Towang over Bum La.

The tasks given to 7 Brigade bore no relationship to its capability. Its primary task was spelt out as the defence of Towang. Preventing any penetration of the McMahon Line, setting up of and assistance to the Assam Rifles’ posts, were its other tasks. Considering that the McMahon Line in Kameng stretched for about 150 kilometres, this solitary brigade was woefully inadequate for these tasks. As it was at the time of the Che Dong incident, it had only two infantry battalions: 9 Punjab and 1 Sikh, both at Towang. Its third battalion – 1/9 Gorkha Rifles – was at Misamari. This battalion had completed its three-year tenure in NEFA and was under move to Yol, where the men’s families were. The battalion earmarked to replace the Gorkhas – 4 Grenadiers – had not yet arrived.The training of 7 Brigade had been neglected. It had done no collective training since its arrival in NEFA. Its men had been employed on tasks unconnected with the brigade’s role. Large numbers were employed for building a helipad at Towang and for the construction of shelters for themselves. The two battalions now with the brigade had a strength of only about 400 men each.

The tasks given to 7 Brigade bore no relationship to its capability. Its primary task was spelt out as the defence of Towang. Preventing any penetration of the McMahon Line, setting up of and assistance to the Assam Rifles’ posts, were its other tasks. Considering that the McMahon Line in Kameng stretched for about 150 kilometres, this solitary brigade was woefully inadequate for these tasks. As it was at the time of the Che Dong incident, it had only two infantry battalions: 9 Punjab and 1 Sikh, both at Towang. Its third battalion – 1/9 Gorkha Rifles – was at Misamari. This battalion had completed its three-year tenure in NEFA and was under move to Yol, where the men’s families were. The battalion earmarked to replace the Gorkhas – 4 Grenadiers – had not yet arrived.The training of 7 Brigade had been neglected. It had done no collective training since its arrival in NEFA. Its men had been employed on tasks unconnected with the brigade’s role. Large numbers were employed for building a helipad at Towang and for the construction of shelters for themselves. The two battalions now with the brigade had a strength of only about 400 men each.

| Editor’s Pick |

Several factors were responsible for this. Both had rear dumps at Misamari and men had to be kept there to look after the battalion equipment and stores. Many men were away on courses and leave and, like other units in the Army at the time, these battalions had been ‘milked’ for new raisings. Then there was the question of maintenance and supply. All troops at Towang and beyond were on air-supply. This restricted the number that could be maintained there.

Lack of intelligence about Chinese intentions and their preparations was a major deficiency on the Indian side. In the Indian Army’s plans, it was assumed that the Chinese would not be able to deploy more than a regiment (brigade) against Kameng.3 Apparently, the assumption was tailored to suit the Indian capability at the time. In the event, the Chinese brought up more than two divisions into Kameng. At best, Indian assessments were guesswork.

As an example, one might quote the briefing given by Brigadier (later Major General) D.K. Palit, Director of Military Operations at Army Headquarters, when he paid a visit to 4 Division in August 1962, barely two months before the invasion. He is said to have stated that for the next few years there was no question of a hot war with the Chinese as they were incapable of mounting a serious offensive till the completion of their rail-link with Lhasa some time in 1964,

Lack of intelligence about Chinese intentions and their preparations was a major deficiency on the Indian side.

Surprisingly, in this guessing game, General Kaul hit the bull’s eye. In his autobiography, he mentions a meeting in March 1962 with Chester Bowles, Special Representative of President Kennedy of the United States, at which he expressed the view that ‘the Chinese were likely to provoke a clash with us in the summer or autumn of 1962’.4 The General’s prophecy proved correct. Evidently, he had kept his side (Palit) in the dark, otherwise he would not have gone around telling people not to expect a Chinese offensive till 1964. Curiously enough, Kaul himself was on vacation at the time of the crisis that he had so correctly forecast.

The Chinese had undertaken a close study of Japan’s victorious campaigns in the Second World War. They employed Japanese tactics to good effect in Korea against UN forces; they were now to use them against the Indian Army. They moved a general who had proved himself in Korea to command their troops in Tibet. Many officers of the Indian Army had fought the Japanese during the Second World War. Also, a study of their campaigns in Malaya, Singapore and Burma formed a part of the syllabus for several examinations for Army officers. But those who were at the helm in October-November 1962 made little use of this knowledge.

The Chinese planned their campaign with meticulous care. They established their forward dumps and stocked them well. They had an assured system of supply to forward troops. For this, they recruited thousands of Tibetan porters and organized them into labour battalions. They also had hundreds of ponies. In mountain and jungle warfare, it is necessary to guard against a breakdown of communications between formations and units. The Chinese insured against such breakdowns by providing their units with powerful radio sets. The Signals set-up of the Indian Army was as outdated as its weapons and woefully inefficient.

Chinese intelligence was no guesswork. They had an effective spy network in India both at strategic and operational levels. In Kameng, they had begun their spying activity two years earlier. Agents were planted among road-gangs, porters and muleteers. These agents were later to guide Chinese columns through NEFA. At Chaku, halfway between Misamari and Bomdi La, a high-ranking Chinese agent had been working at a roadside teashop that had two Monpa belles as an added attraction. It was later discovered that even junior Chinese commanders, disguised as Tibetans, had reconnoitred the area of their future operations. The Chinese knew a good deal about the weapons and tactical concepts of the Indian Army – the Indians had laid on a demonstration for them! On the other hand, the publication of a pamphlet on the Chinese Army had been banned by the Indian Government.Surprise and deception play an important role in war. The Chinese did not show their hand till the last moment. At the political level, they kept up the stance of friendliness and their willingness to negotiate. Militarily, they reacted lightly to moves by Indian troops, so as to draw them into deeper waters. A few weeks before the Che Dong incident, Defence Minister Krishna Menon had a chance meeting at Geneva with the Chinese Foreign Minister, Marshal Chenyi.

Chinese intelligence was no guesswork. They had an effective spy network in India both at strategic and operational levels. In Kameng, they had begun their spying activity two years earlier. Agents were planted among road-gangs, porters and muleteers. These agents were later to guide Chinese columns through NEFA. At Chaku, halfway between Misamari and Bomdi La, a high-ranking Chinese agent had been working at a roadside teashop that had two Monpa belles as an added attraction. It was later discovered that even junior Chinese commanders, disguised as Tibetans, had reconnoitred the area of their future operations. The Chinese knew a good deal about the weapons and tactical concepts of the Indian Army – the Indians had laid on a demonstration for them! On the other hand, the publication of a pamphlet on the Chinese Army had been banned by the Indian Government.Surprise and deception play an important role in war. The Chinese did not show their hand till the last moment. At the political level, they kept up the stance of friendliness and their willingness to negotiate. Militarily, they reacted lightly to moves by Indian troops, so as to draw them into deeper waters. A few weeks before the Che Dong incident, Defence Minister Krishna Menon had a chance meeting at Geneva with the Chinese Foreign Minister, Marshal Chenyi.

The latter is said to have given Menon an assurance ‘that China wanted a peaceful settlement of the border dispute and. . . whatever happened China would never resort to war to settle this issue’.5 The Chinese kept up their diplomatic correspondence till the end, urging the Indian Government to resume negotiations, though they were not prepared to quit Indian territory occupied by them in Ladakh. The Galwan incident was also a part of the deception. It succeeded in conveying the impression that Chinese reactions to the occupation of disputed territory might result in confrontation, but not war.

But there was nothing to stop those in authority from following the normal procedure for undertaking a military operation

At Che Dong, the Chinese move conformed to the pattern of their action at Galwan. They surrounded the Indian post on three sides. After a few days, the post commander admitted that in his first report he had inflated the number of Chinese troops facing him in order to get help quickly and that there were only 60 or so of them, not 600. However, the first report of 600 Chinese debouching across Thag La appears to have conveyed to the Indian authorities the impression that this was the implementation of China’s oft-repeated threat of moving across the McMahon Line in case India’s forward moves into Chinese-claimed territory in Ladakh did not cease. That perhaps accounted for the different line of action in the case of this incident. In Ladakh, in such situations, Indian troops had merely been told to hold their ground. In this case, the orders were to evict the Chinese. The aim, perhaps, was to deter further intrusions.

Let us now take a look at the reactions of Indian field commanders to the message from the Che Dong Post. On 8 September, Brigadier Dalvi was at Tezpur. He had been granted his annual leave and was to catch the next morning’s flight homeward. He was in a holiday mood. Having played a round of golf with Niranjan Prasad in the evening, he was in his bath when the telephone rang to inform him of the incident. He realized that this was the end of his leave.

At Divisional Headquarters, there was the usual weekend atmosphere, 8 September being a Saturday. Niranjan Prasad had to be summoned from the Planters’ Club at Thakurbari, 32 kilometres away. It took some time to collect the concerned staff officers and a conference was eventually held, at which certain immediate measures were decided upon. A helicopter took Dalvi back to Towang the next morning. At this time, one company of 9 Punjab was at Shakti and another company was under move to Lumpu. Dalvi now ordered the whole battalion to move to Lumpu and send out reconnaissance patrols to the Namka Chu. The Assam Rifles had a wing at Lum La. He told them to send a platoon to reinforce the Che Dong Post. The post commander had already been ordered to hold his ground. The other battalion at Towang, 1 Sikh, had a company forward, at Pankentang. Dalvi ordered the battalion to send a company forward to Milakteng La.

| Editor’s Pick |

On 10 September, Niranjan Prasad arrived at Towang. He had with him a radio signal from Eastern Command, which had been sent as a result of the meeting in the Defence Minister’s office the previous day. The message ordered the immediate move of 9 Punjab to the Che Dong area; the rest of the brigade was to get ready to join the battalion within 48 hours. The message said that all troops should go prepared for battle and, if possible, an attempt was to be made to encircle the Chinese investing Dhola Post. The operation was given the code name ‘Leghorn’.

Besides bringing him these orders, Prasad told Dalvi that his brigade was to be reinforced. For this purpose, 2 Rajput had been placed under him and ordered to move up straightaway. This battalion had done a three-year tenure in the Walong sector and had been at Charduar the last few months, awaiting a move to a family station. It had already handed over its radio sets, entrenching tools and other equipment to the relieving unit at Walong. Another addition to the brigade would be its old battalion, 1/9 Gorkha Rifles, which was still at Misamari. It must have been quite a shock to the men of these two battalions when their dreams of rejoining their families were thus shattered.

A great deal of the confusion that took place in the implementation of the Government’s order was due to lack of knowledge of the terrain on the part of higher commanders. They sent orders which were impracticable. When moves were ordered to build up 7 Brigade, no thought was given to the problems of movement in the mountains, or to the logistic support of the troops inducted. It does not seem to have been realized that in the mountains it might take a whole day for a body of troops to cover a distance that is marked as 10 or 12 kilometres on the map. General Sen did not even consider it worthwhile to familiarize himself with the area in which 7 Brigade was to operate. Between 8 and 19 September, the period during which he ordered many crucial moves, he paid several visits to Delhi but none to the Namka Chu. Ignorance of the conditions in the theatre of operations led him to make rash promises. At a conference in the Defence Minister’s room on 11 September, he stated that to neutralize the Chinese, at that time reported to be about 600, he would need a brigade and that he had ordered the move of the brigade, which would concentrate in ten days.6 In the event, the brigade had not concentrated even by 5 October, when Kaul reached the scene.

Important decisions were taken on 11 September. Among these was the warning order to 62 Infantry Brigade, then at Ramgarh (Bihar), for move to NEFA. Another decision was that in the operations against the Chinese close air support would not be permitted. Fear of reprisals was responsible for this decision.

At Che Dong, the Chinese move conformed to the pattern of their action at Galwan. They surrounded the Indian post on three sides.

Unquestioned compliance with the wishes of political leaders marked the actions of the Army Headquarters at this time. They did not consult the field commanders before making promises to the Government. Apologists might take shelter behind the principle of civil supremacy. But there was nothing to stop those in authority from following the normal procedure for undertaking a military operation; and in case an appreciation by the field commander showed that it had no chance of success, the civil authority should have been told. It would then have been the Government’s business to think of other means to deal with the situation.

The first man to stand up and argue was Lieutenant General Umrao Singh. He did this when he met Sen and Niranjan Prasad at Tezpur on 12 September. He told Sen that he felt strongly about 7 Brigade being hustled into the impossible venture of evicting the Chinese from Thag La. He pointed out that the troops were on restricted rations as bad weather had been interfering with air-drops and that they had no reserves. They would have to operate at altitudes up to 5,250 metres; winter was approaching and they would need heavy clothing and tents. The sensible course, he suggested, was to withdraw the Che Dong Post to the map-marked boundary and in case this was unacceptable for political reasons, to commit only two battalions, which should be deployed South of the map-marked McMahon Line, to meet any further advance by the Chinese. However, Umrao Singh’s arguments and suggestions fell on deaf ears; Sen merely reaffirned his earlier orders.

Relations between Sen and Umrao Singh were known to be strained. But, in marshalling his reasons against Operation ‘Leghorn’, the latter was not bringing in his personal feelings. After Sen’s refusal to heed his advice, he followed up with a formal letter reiterating his views.

Meanwhile, 9 Punjab was on its way to the Namka Chu under its commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel R.N. Misra. The battalion had established a base at Lumpu, which had a helipad and a dropping zone.

Mid-September was harvesting time in these parts. No ponies or porters were available and 9 Punjab had to carry everything manpack. The men moved with one blanket, a hundred rounds of ammunition, two grenades, three days’ rations and their share of light machine-gun magazines. The total load per man was 30 to 35 kilograms. The battalion took the Hathung La route from Lumpu and after a day’s forced march, reached Bridge I late in the evening on 14 September. There they bivouacked for the night. The next morning, after dropping one company at Bridge I, Misra took the rest of the battalion to Bridge II, where a company of Chinese troops was in position on both sides of the Namka Chu. The bridge had been damaged, but could still be used by one or two men at a time. The Chinese had a civilian official with them.

On seeing the Punjabis’ column, the Chinese South of the river began to shout in Hindi that the Indians should withdraw from the Kachilang (their name for the Namka Chu) area, as it was Chinese territory. They said that there was ‘unbreakable’ friendship between the Indian and Chinese people, which should not be marred by petty incidents. They claimed to be frontier guards and asked why India had moved regular troops. Finally, they asked the Punjabis to send the local Indian civil official to discuss the exact location of the boundary so as to reach an amicable settlement and prevent firing and bloodshed. Misra conveyed the Chinese request to the brigade; thereafter it was relayed up the command ladder right up to Delhi.7Misra’s orders were to fire only in self-defence and to sit in front of the Chinese if they refused to vacate Indian territory. He, therefore, left two of his companies about 50 metres South of the Chinese position at Bridge II and led the remaining company to Che Dong, which was reached at 1400 hours. Misra found that the logs on Bridge III had been destroyed and a Chinese detachment, about 50 in strength, was holding a position North of the river, facing the Assam Rifles. He learnt that they had occupied this position after the Assam Rifles had reinforced their post on 13 September from the Lum La wing. Misra deployed his company on the South bank, facing the Chinese. Three days later, he sent a detachment from this company to occupy a position on Tsangdhar, which overlooked both Bridges III and IV.

On seeing the Punjabis’ column, the Chinese South of the river began to shout in Hindi that the Indians should withdraw from the Kachilang (their name for the Namka Chu) area, as it was Chinese territory. They said that there was ‘unbreakable’ friendship between the Indian and Chinese people, which should not be marred by petty incidents. They claimed to be frontier guards and asked why India had moved regular troops. Finally, they asked the Punjabis to send the local Indian civil official to discuss the exact location of the boundary so as to reach an amicable settlement and prevent firing and bloodshed. Misra conveyed the Chinese request to the brigade; thereafter it was relayed up the command ladder right up to Delhi.7Misra’s orders were to fire only in self-defence and to sit in front of the Chinese if they refused to vacate Indian territory. He, therefore, left two of his companies about 50 metres South of the Chinese position at Bridge II and led the remaining company to Che Dong, which was reached at 1400 hours. Misra found that the logs on Bridge III had been destroyed and a Chinese detachment, about 50 in strength, was holding a position North of the river, facing the Assam Rifles. He learnt that they had occupied this position after the Assam Rifles had reinforced their post on 13 September from the Lum La wing. Misra deployed his company on the South bank, facing the Chinese. Three days later, he sent a detachment from this company to occupy a position on Tsangdhar, which overlooked both Bridges III and IV.

That night (15 September), 9 Punjab at Bridge II carried out a clever manoeuvre. They crept closer to the bridge. The Chinese started shouting but withdrew to the North bank, leaving two sentries on the South bank.

The close proximity in which Indian and Chinese troops were placed along the river was bound to lead to trouble sooner or later.

During these early days of the confrontation, the Chinese showed keenness to fraternize with the Indians. They would offer cigarettes and make over some of the parachuted supplies landing in their lines. They would announce over loudspeakers in Hindi that the two Governments would soon begin talks to settle the boundary question and advised caution so that firing should not spoil the chances of peace. But they did not neglect their preparations and continued to strengthen their defences by building bunkers and clearing lines of fire. They were well equipped for the purpose and had mechanically operated saws to cut logs. while Indian troops had to depend on dahs, even shovels, for this purpose.

On 19 September, the Punjabis received an intriguing radio signal. It was from Army Headquarters and addressed to everyone in the chain of command down to the battalion. Sent on 15 September, it had taken four days to reach 9 Punjab. It ordered the battalion to capture, as soon as possible after arrival on the Namka Chu, the Chinese position 900 metres North-East of Che Dong, contain the Chinese South of Thag La and, if possible, establish two posts atop the Thag La Ridge (height over 5,250 metres).

This message is clear proof that the Indian high command did not understand the Chinese, the situation at hand or have any idea of their capability. It had been issued after a report had reached the Government that the Chinese facing Che Dong numbered 60 and not 600. Those in authority should have, by this time, realized that the Chinese seldom made any move without due preparation and that the 60 on the river could soon be reinforced to many times that number. In fact, by the time the Punjabis had reached the Namka Chu, the Chinese already had two companies between the river and the Thag La Ridge. On 16 September, a third company arrived and local intelligence reports put another infantry battalion at Le. Under the circumstances, execution of the order from Army Headquarters would have meant annihilation of the attacking force.

| Editor’s Pick |

When this order reached 9 Punjab, Dalvi was on an inspection tour of the battalion. He told Misra to take no notice of it, and informed Niranjan Prasad of his action. The latter protested to 33 Corps regarding the propriety of this order being given direct to one of the units under him. Umrao Singh, in his turn, asked Eastern Command to have the order cancelled. 9 Punjab were at this time living on rice and salt; they did not even have sugar for their tea. Perhaps this did not interest those who issued the order.

The close proximity in which Indian and Chinese troops were placed along the river was bound to lead to trouble sooner or later. The night of 20 September8 saw the first outbreak of firing. Around 2230 hours, a Chinese sentry on Bridge II lobbed a grenade into one of the Punjabis’ bunkers. Thereupon the latter opened fire, killing one Chinese soldier on the South bank and another across the bridge. Intermittent firing continued throughout the night. The Punjabis suffered four casualties as wounded.

Headquarters 7 Brigade moved to Lumpu by the time Dalvi finished going round the 9 Punjab positions. There were other moves too. Tactical Headquarters 4 Division started moving to Towang and 7 Brigade was relieved of the responsibility for the Bum La -Towang axis. Its defence was entrusted to Headquarters 4 Division Artillery Brigade under Brigadier (later Major General) Kalyan Singh. It began moving to Towang, and 1 Sikh was placed under it. Another change was the removal of 5 Brigade from the operational control of 4 Division; henceforth it was to be directly under Headquarters 33 Corps and 4 Division was made solely responsible for Kameng. Effectively, when this shuffling took place Headquarters 4 Division had only 7 Brigade under it. Other formations were to join piecemeal later.

The outbreak of firing on the Namka Chu and reports of the Chinese build-up induced General Thapar to ask the Government to reconsider its decision regarding Operation ‘Leghorn’. Nehru and Menon were both abroad at this time and Thapar presented his case at a meeting that was held under the aegis of the Deputy Defence Minister, K. Raghuramaiah, on 22 September. The Army Chief stated that the Chinese could react to Indian moves on the Namka Chu by sending more reinforcements against that position; they could also commence operations elsewhere in NEFA or in Ladakh. The Foreign Secretary, who was present, explained the Prime Minister’s instructions on the subject and stated the Government’s view that no infringement of the border in NEFA was to be accepted. He was of the opinion that the Army must build up in the Namka Chu area and evict the Chinese from Indian territory there even at the cost of Chinese reaction in Ladakh. He stated that the Chinese would not react strongly in Ladakh but might only try and capture a post or two.

“¦the operation was to be a probe in strength to gauge Chinese reaction. The plan catered neither for a further Chinese build-up nor for their counter-action.

His advice having been overruled, Thapar asked for written orders from the Government. As a result, he received a note signed by a Joint Secretary, to the effect that there was no change in the Government’s previous stand in the matter, and that the COAS should take action for the eviction of the Chinese in the Kameng Frontier Division of NEFA as soon as he was ready. Thapar repeated the Government’s orders to Sen, with the injunction that arrangements be made for the eviction of the Chinese at ‘top speed’. At the same time, he warned Western Command of the possibility of Chinese reaction in Ladakh and ordered that Indian posts there should be strengthened.

The responsibility of preparing a plan for Operation ‘Leghorn’ fell on Brigadier Dalvi. As he later wrote, the task of evicting the Chinese was militarily impossible and the modest plan that he evolved ‘under duress from the Chief’ was in the nature of a police action. He did not envisage a set-piece attack to capture the Chinese positions on Thagla; the operation was to be a probe in strength to gauge Chinese reaction. The plan catered neither for a further Chinese build-up nor for their counter-action.9

The Thag La Ridge sloped from West to East and its Southern face was steep. This ruled out an approach from the East as also a frontal attack across the river. The only practical approach was from Tsangle in the extreme West of the valley. Dalvi’s plan, therefore, envisaged an out flanking move from Bridge V to capture Tseng-jong, a small feature on the Thag La slopes. After its capture, the assault force would roll down to the Chinese positions on the Namka Chu. The move of this force from Lumpu was to be carried out in stages and he allowed ten days for the approach march. While working out the logistics for this plan, Dalvi asked for the stockpiling of 30 days’ rations, three first line scales of ammunition, snow-clothing and other equipment, provision of artillery, helicopters for evacuation of casualties and porters for the loads from Tsangdhar onwards. Winter was approaching and he made it clear that unless the logistic base was ready within a fortnight, there would be no scope for operations before April next.

On 25 September, Niranjan Prasad arrived at Dalvi’s Headquarters at Lumpu. He studied the plan and made some alterations. The next day, Umrao Singh helicoptered to Lumpu and discussed it in detail with both of them. He wanted more fire-power and a higher administrative build-up to be catered for and objected to the laying down of firm dates. He insisted upon a line of action that would have a chance of success, even if the execution had to wait for six months. The plan was then modified in, the light of his advice and he took it with him. Before leaving, he ordered that there was to be no concentration of troops ahead of Lumpu till essential stores and equipment were in position at Tsangdhar.

Umrao Singh took Dalvi’s plan, as modified to Lucknow on 29 September. Sen refused to accept the requirements stipulated for the operation; it would have been impossible to meet them before the onset of winter. His views about the situation having been rejected for a second time, Umrao Singh went back to his Headquarters and despatched a written protest. A few days earlier, he had received a radio signal from Sen telling him to send a company-strength patrol to Tsangle with a view to establishing a post there. This ordering of companies and platoons by Sen was seen by the Corps Commander as interference in his command and he protested about this too.Sen brought Umrao Singh’s objections and protests to the notice of the COAS. Both Sen and Thapar were now in a quandary of their own creation; they had earlier assured the Government that the eviction was feasible. The Government had also taken an unwise step in leaking out the eviction order and reports had appeared in the foreign and Indian Press regarding the impending military action. The Chinese move against the Che Dong Post had earlier been reported in the Press. The shooting incidents that occurred thereafter made the Indian public impatient for action.

Umrao Singh took Dalvi’s plan, as modified to Lucknow on 29 September. Sen refused to accept the requirements stipulated for the operation; it would have been impossible to meet them before the onset of winter. His views about the situation having been rejected for a second time, Umrao Singh went back to his Headquarters and despatched a written protest. A few days earlier, he had received a radio signal from Sen telling him to send a company-strength patrol to Tsangle with a view to establishing a post there. This ordering of companies and platoons by Sen was seen by the Corps Commander as interference in his command and he protested about this too.Sen brought Umrao Singh’s objections and protests to the notice of the COAS. Both Sen and Thapar were now in a quandary of their own creation; they had earlier assured the Government that the eviction was feasible. The Government had also taken an unwise step in leaking out the eviction order and reports had appeared in the foreign and Indian Press regarding the impending military action. The Chinese move against the Che Dong Post had earlier been reported in the Press. The shooting incidents that occurred thereafter made the Indian public impatient for action.

Prisoners of their own commitments, Thapar and Sen had now to find a way out of the impasse created by Umrao Singh’s stand. The easiest way out was to replace him by a more pliant Corps Commander and this course is said to have been suggested to Menon after he returned to Delhi on 30 September. However, on Nehru’s return from abroad two days later, it was decided to form 4 Corps to handle Operation ‘Leghorn’. Umrao Singh was to be left in command of 33 Corps, the only change being that NEFA would no longer be under his jurisdiction.

The Government had also taken an unwise step in leaking out the eviction order and reports had appeared in the foreign and Indian Press regarding the impending military action.

During the Second World War, 4 Corps had been largely responsible for throwing the Japanese out of India. Now, the newly raised 4 Corps was to throw the Chinese out of NEFA. The Government entrusted its command to Kaul, who had been recalled from leave on 3 October. It is unusual for an officer holding a senior appointment like the CGS to step down and take charge of a job of lower status. But 4 Corps was no ordinary corps. It was to carry out a task dubbed impossible by another corps commander. It was perhaps a unique instance in military history that a newly formed corps-level formation had to plunge into operations straightaway. Significantly, no fresh appointment of CGS was made after Kaul left to command 4 Corps and the post was kept vacant at a time when crucial operations were about to be undertaken. The expectation perhaps was that Kaul would soon be back in Delhi after chasing the Chinese across Thag La. According to some sources, Kaul volunteered for the command of 4 Corps.

On 4 October, Kaul flew to Tezpur to take up his new appointment. His corps would have its Headquarters there. He took with him a few key officers to function as his staff. The previous night he had gone to meet the Prime Minister at the latter’s residence. At this meeting, Nehru told him the reasons that had led him to order the action at Che Dong. These were substantially the same as given by the Foreign Secretary to Thapar on 22 September. According to Kaul, Nehru said that a stage had come when India ‘must take – or appear to take – a strong stand irrespective of consequences’. In Nehru’s view, the Chinese, by their action on the Namka Chu, were establishing their claim on NEFA, which must be contested. He considered that if the Government failed to act it would forfeit public confidence.10 The fact that the disputed place did not lie in Indian territory on India’s own maps was evidently forgotten.

When Kaul landed at Tezpur, he was received by Sen and Umrao Singh. It was unusual for an Army Commander to go and receive a Corps Commander under his command. But Kaul was no ordinary Corps Commander. He was the Supremo, armed with special powers to report directly to the Prime Minister. Newspapers had announced his appointment in big headlines, though the creation of a new operational formation and the name of its commander should have been kept secret in accordance with normal practice. The Press reports said that Kaul had been specially assigned the task of forcing the Chinese back over the Thag La Ridge.

The main reason was the shortage of porters to move the air-dropped supplies from Lumpu.

Let us take a look at the situation in Kameng on 4 October. The two infantry battalions (2 Rajput and 1/9 Gorkha Rifles) ordered to join 7 Brigade had reached Lumpu. Both units were in cotton uniforms and without essential equipment, many of the men even without boots. They had moved from the plains in heavy rains when the Foot Hills-Towang road had become slushy and unfit for vehicular traffic. They marched most of the way, spending the nights in the open under improvised shelters. Neither unit was fit for war. 4 Grenadiers, earlier earmarked to replace 1/9 Gorkha Rifles, had arrived at Towang towards the end of September.

The build-up at Tsangdhar was slow. The main reason was the shortage of porters to move the air-dropped supplies from Lumpu. Tsangdhar had a small flat area that could be used for drops in an emergency. Towards the end of September, it was brought into use to hasten the build-up. But due to the limitations of the dropping zone there were heavy losses. The parachutes landed in ravines from which it was difficult to retrieve the stores. Unfortunately, the drops were also not planned properly. While the troops needed items like ammunition and snow-clothing, they were getting tent-pegs; kerosene oil was being dropped in large 200-litre barrels, weighing over 200 kilograms each. No thought was given to the fact that the men would have to roll them up and down steep slopes. When Packets (C-119) were pressed into service, the losses mounted, as much as 80 per cent being lost on one day. The comparatively high speed of the Packet reduced its suitability for drops at Tsangdhar. Bad weather also began to interfere with dropping operations and Tsangdhar had its first snowfall on 1 October.

| Editor’s Pick |

The Chinese had by then deployed a regiment (brigade) in the Thag La area. They were also active in front of Khinzemane and Bum La. Intermittent exchange of fire in the Bridge II area had continued till 30 September. Both sides suffered casualties but 9 Punjab had an edge over the Chinese in these exchanges. Against the advice given by Dalvi, who was supported in this by Prasad and Umrao Singh, Sen had been insisting on the occupation of Tsangle. Ultimately, Dalvi had to give in, and the Punjabis set up a company locality there.

In the way of support weapons, two platoons of medium machine guns from 6 Mahar were available to 7 Brigade. Also 34 Heavy Mortar Battery, less a troop, had reached Lumpu; but it had no ammunition. After some Chinese wheeled guns were spotted on Thag La, a troop of 75-mm guns from 17 Parachute Field Regiment was flown from Agra to Tezpur; the guns were later to be dropped at Tsangdhar.

From Ramgarh, 62 Brigade had moved with its three infantry battalions 4 Garhwal, 2/8 Gorkha Rifles and 4 Sikh. En route, the Sikhs and the Gorkhas had been diverted to the Walong sector. The Headquarters of 62 Brigade and 4 Garhwal had reached Charduar and were awaiting further orders.

Before leaving, he (Gen Kaul) sent off a message to Army Headquarters to alert the Air Force for the use of fighter aircraft to combat the Chinese Air Force if such a contingency arose.

Around 0930 hours on 4 October, Niranjan Prasad arrived at Lumpu. After breaking the news of the formation of the new corps, he told Dalvi to move with his reconnaissance group to Tsangdhar immediately. Dalvi was taken aback and pointed out that he had received no operation order that would necessitate his move to Tsangdhar; also that by making a start at that hour, there would be no chance of completing a day’s march. But Niranjan Prasad seemed to be under great compulsion. According to Dalvi, the general ‘begged’ him to leave at once, ‘and take shelter in the nearest herder’s hut; all that mattered was that he [Prasad] should be in a position to say that the commander had gone “forward”’. This left no choice for Dalvi and shortly before noon he set out for Tsangdhar by way of Karpo La I. With him were the commanding officers of 2 Rajput and 1/9 Gorkha Rifles. About three kilometres from Lumpu, the party camped at a herder’s hut and reached Tsangdhar around midday on 6 October. No tents were available there and they used parachutes for shelter.

Coming back to General Kaul at Tezpur on 4 October, we find him being briefed by Sen and Umrao Singh. After the briefing, he plunged into the task he had taken on. To get over the shortage of porters, he ‘commandeered’ about a thousand of them from the Border Roads Organization and informed Delhi of his action. He was determined to get 7 Brigade to the Namka Chu in time for the eviction operation. In the Dalvi Plan, as sent up by Lieutenant General Umrao Singh, 10 October had been specified as the date by which Operation ‘Leghorn’ would have to commence if the logistics base was ready. Kaul decided to treat this date as a deadline, regardless of logistics. With this in view, he ordered the two battalions at Lumpu to move to Tsangdhar the next day, although they had not yet been equipped and the build-up of supplies and ammunition was woefully low. He also ordered 4 Garhwal to Towang to reinforce the garrison there. Headquarters 62 Brigade was left at Charduar, doing nothing.

On the morning of 5 October, Kaul set out for the front after telling his staff that he would not return till Operation ‘Leghorn’ was over. He was seen off at the airport by Sen and Umrao Singh. Before leaving, he sent off a message to Army Headquarters to alert the Air Force for the use of fighter aircraft to combat the Chinese Air Force if such a contingency arose. The message also requested consideration of close air support should it be necessary for carrying out the eviction operation.Kaul knew that the Government had decided against close air support. Apparently, after the briefing by Umrao Singh, his outlook on the feasibility of Operation ‘Leghorn’ had changed. It was to change further when his helicopter landed at Ziminthang, a short distance from Lumpu and he met an intelligence agent. The latter told him that the Chinese had at least a regiment at Thag La, with artillery, heavy mortars and recoilless guns.11 Straightaway, he sent off another radio signal to Eastern Command and Army Headquarters.

On the morning of 5 October, Kaul set out for the front after telling his staff that he would not return till Operation ‘Leghorn’ was over. He was seen off at the airport by Sen and Umrao Singh. Before leaving, he sent off a message to Army Headquarters to alert the Air Force for the use of fighter aircraft to combat the Chinese Air Force if such a contingency arose. The message also requested consideration of close air support should it be necessary for carrying out the eviction operation.Kaul knew that the Government had decided against close air support. Apparently, after the briefing by Umrao Singh, his outlook on the feasibility of Operation ‘Leghorn’ had changed. It was to change further when his helicopter landed at Ziminthang, a short distance from Lumpu and he met an intelligence agent. The latter told him that the Chinese had at least a regiment at Thag La, with artillery, heavy mortars and recoilless guns.11 Straightaway, he sent off another radio signal to Eastern Command and Army Headquarters.

This message stated that in view of Chinese superiority in resources, he could not rule out the possibility of the Indian force being overwhelmed; and that unless the situation was ‘retrieved’ there might be a ‘national disaster’. As a precautionary measure, he again recommended that offensive air support be positioned.

It forecast heavy casualties in the initial stages and asked for evacuation arrangements.

Having sent this signal Kaul flew into Lumpu, where he arrived at about 1500 hours. When he found that the two battalions there had not yet moved to Tsangdhar, he was very annoyed and ordered an immediate start. The brigade major (the brigade operational staff officer) pointed out that the distance covered at night in that terrain would be negligible and that Tsangdhar still needed to be stocked with rations, ammunition, blankets, snow-clothing and other necessaries. He also said that no porters were available; the men would have to move on hard scales and the sick rate would go up if the troops were sent without adequate clothing. Kaul overruled the brigade major and ordered that the brigade must concentrate at Tsangdhar by the evening of 7 October. He, however, promised that he would hasten the despatch of their equipment and stores.

A staging-post had been established at Serkhim, on the Lumpu-Hathung La route. On 6 October, Kaul flew to Serkhim; a helipad had been constructed there overnight by 100 Field Company. Thence Kaul and his party, which included Niranjan Prasad, made for the Namka Chu. The journey included a three-and-a-half-hour climb to Hathung La. It was arduous even for acclimatized troops; but Kaul was in a hurry and had himself carried pick-a-back part of the way by a porter. Seeing their Corps Commander carried in this fashion could not have been an inspiring sight for the troops.

Reaching Bridge I that evening, Kaul spent 7 October going round Indian positions. He could now see for himself that the troops were in a death trap; their positions were dominated by the Chinese all along. He met Dalvi in the afternoon, when the latter briefed him on the serious shortages of his brigade, as also the progress of 1/9 Gorkha Rifles and 2 Rajput.

He (Gen Kaul) then pointed out that even if initial success was gained, the Chinese were bound to counter-attack and throw the Indians from positions they might capture.

These two battalions, 34 Heavy Mortar Battery (less a troop), a company of 6 Mahar (machine guns), less the platoon already at Che Dong and most of 7 Brigade Headquarters reached Tsangdhar around 1700 hours that day. Only a few porters were available and all equipment in any case had to be carried manpack. These units had travelled via Karpo La I (5,250 metres) and on arrival at Tsangdhar (4,790 metres), the men had bivouacked in the open in freezing cold, with groups of three sleeping under two ground-sheets. The two battalions were still in cotton uniforms and the exposure brought on a good deal of sickness: chilblains, frostbite and pulmonary disorders. Two men of 1/9 Gorkha Rifles died of pulmonary oedema the next day.

Kaul sent three radio signals on 7 October to Lucknow and Delhi. The state of communications had not improved and the first message reached Delhi after three days. It forecast heavy casualties in the initial stages and asked for evacuation arrangements. The subsequent messages portrayed the difficult nature of the terrain, the precarious situation of Indian troops, assessment of Chinese strength and the unsatisfactory position of supplies and equipment. After recounting the difficulties of the situation, Kaul went on to say that despite these he was taking every step to carry out the orders he had received from the COAS and the Government. He then pointed out that even if initial success was gained, the Chinese were bound to counter-attack and throw the Indians from positions they might capture. To counter this, he recommended the marshalling ‘of all military [sic] and air resources’ for ‘restoration of the position in our favour’.

If Kaul had studied the reports sent by Dalvi and the recommendations of Umrao Singh before setting out from Delhi, he need not have come all the way to the Namka Chu to convey to the COAS and the Government the difficulties in the way of Operation ‘Leghorn’. Even at this stage, there was nothing to stop Kaul from recommending that the operation be called off for the time being. It was perhaps the Prime Minister’s injunction that came in the way.

On 8 October, Kaul held a conference near Bridge IV. It was meant to be an operational conference but turned out to be a rambling discussion of possible moves, interspersed with anecdotes. At one stage, a burst from a Chinese weapon from across the river broke up the conference, with everyone taking cover. After a lengthy pow-wow, Kaul’s final decision was that due to the physical impossibility of evicting the Chinese from their strong positions, he would make a ‘positional warfare manoeuvre’ and occupy Yumtso La, a feature the Chinese had not yet occupied. It lay West of Thag La and Kaul nominated 2 Rajput for the task.

| Editor’s Pick |

Kaul’s announcement astonished his audience: the mission was suicidal. It involved the move of a battalion in cotton uniforms from the floor of the Namka Chu Valley to a mountain that was about 5,250 metres above sea-level. The move would take place under the very noses of the Chinese and without artillery support. They could massacre the battalion en route; even if they allowed the move to take place, the men would freeze to death on Yumtso La. The Chinese could also starve the Rajputs after they were in position by merely cutting off their lines of communication.

When these possibilities were pointed out to Kaul, he brushed them aside. But he accepted Dalvi’s suggestion that as a first step a patrol from 9 Punjab should be sent. The battalion knew the area and the patrol’s task would be to find a suitable crossing-place for the Rajputs and occupy Tseng-jong, a small feature on Thag La slopes, from which the Rajputs’ move could be covered. The Rajputs, less a company, were to advance at first light on 10 October. One company of this battalion was already deployed at Bridge I.

Even at this stage, there was nothing to stop Kaul from recommending that the operation be called off for the time being.

The Punjabis despatched a platoon to Tseng-jong soon after the decision was taken and occupied the feature without opposition. Before nightfall, two companies of the Rajputs had reached the Bridge IV area; the rest of the battalion (less the company at Bridge I) was deployed in the Dhola Post area. The Gorkhas had taken up positions on the Northern slopes of Tsangdhar, above Bridge III.

That night, Kaul jubilantly reported the occupation of Tseng-jong to Eastern Command and Army Headquarters. At the same time, he asked for the despatch of 11 Brigade to Lumpu to meet the anticipated Chinese reaction. It does not need much imagination to realize that in the conditions then prevailing, it would have taken some weeks for 11 Brigade (then in Nagaland) to reach Lumpu. Perhaps the Chinese were expected to be on their best behaviour till Kaul had his second brigade in position.

On 9 October, 9 Punjab reinforced the position at Tseng-jong with a platoon from their company at Tsangle, a section being sent up to the spur of Karpo La II, West of Yumtso La. The Chinese too were seen to reinforce their positions towards Tseng-jong. Kaul received a message that day from Army Headquarters conveying an intelligence report that about 300 mortars and guns had been seen moving near Tsona Dzong towards the McMahon Line and that their objective might be Towang. The message is an indication of the paralysis that gripped those in authority at this time. Army Headquarters knew that the only guns with 7 Brigade were two 75-mm (Para) field guns from 17 (Para) Field Regiment air-dropped at Tsangdhar and a troop (4 pieces) of 4.2-inch mortars (without ammunition). Sending this message to the Corps Commander without telling him what they intended to do about it was a meaningless exercise on the part of Army Headquarters. At this time Towang had three batteries (two mountain, one field) and a troop of 4.2-inch mortars.

The Para Gunners had come by road from Tezpur and were suffering from the effects of high altitude, like other troops rushed up from the plains without acclimatization. Four of the guns had been dropped at Tsangdhar on 8 October. Of these, it had been possible to retrieve only two. Even the two pieces could give no solace to the men on the Namka Chu as they were outranged by Chinese infantry mortars.

The Para Gunners had come by road from Tezpur and were suffering from the effects of high altitude, like other troops rushed up from the plains without acclimatization. Four of the guns had been dropped at Tsangdhar on 8 October. Of these, it had been possible to retrieve only two. Even the two pieces could give no solace to the men on the Namka Chu as they were outranged by Chinese infantry mortars.