IDR Blog

Pakistan has not Learnt the Lessons of 1971

Reflections on September evoke a host of memories.

Chile in September 1973, when the country’s armed forces in collusion with America’s Central Intelligence Agency ousted the socialist government of President Salvador Allende and pushed Chile into a long Pinochet-era darkness.

Many years later, September 11, 2001 happened. Something snapped in the human imagination. Men and women everywhere were made to feel vulnerable when the twin towers came crashing down in New York. Terrorism revealed its ugly face. Life’s beauty was in retreat.

In September 1973, days after blood flowed on the streets of Chile, the scholar-diplomat-poet Pablo Neruda saw life draining out of him. He had been ailing for some time but it was the brutality of the soldiers and the indignity they subjected on him when they ransacked his home that killed him.

At the very end of September 1965, six generals of the Indonesian army lay dead, supposedly victims of an abortive coup, the blame for which was pinned on the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI), the largest communist party outside the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union. A seventh general, Suharto, survived or so we were led to believe. He set out to restore order in the country. He would end up, over the following 32 years, as the head of Indonesia’s most notorious kleptocratic family.

Reflections on September will be half done if one does not travel down memory lane to the September 1965 war between India and Pakistan. That war, as history has so well documented, was a waste of resources and only exacerbated the bitterness between the two countries.

Back then, those of us in our sixties today were in our pre-teens. We were part of Pakistan. In my school, we were informed by our teachers that India had attacked Pakistan and that we ought to do everything to help our soldiers on the battlefield. We contributed to a defence fund, the money coming from the two annas and four annas our parents gave us for tiffin every morning.

On the first day of the war, we heard the President, Field Marshal Mohammad Ayub Khan, tell us of the bravery with which Pakistan’s soldiers were confronting the enemy. We believed him, not realizing that he was being economical with the truth. We did not know then that the war had been brought about by Pakistan, that Operation Gibraltar was in implementation mode, that it was all a plan concocted by the field marshal and his brash young foreign minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to seize all of Kashmir.

The war went on for seventeen days. Ayub Khan first sent Law Minister S.M. Zafar to speak for the country at the United Nations Security Council. The move did not quite work, so Bhutto was dispatched to New York. He spoke eloquently and forcefully and, because we were so young, we cheered him. The adults around us thought he was doing a marvelous job. He was a hero for Pakistanis. It did not matter that he was abusive toward the Indian delegation, led by the respected Sardar Swaran Singh; that he was being indecent and intemperate in language and behaviour.

And there was, of course, Radio Pakistan, consistently dishing out news of the Pakistan army’s ‘victories’ on the battlefield. The Indians, we were told, were losing their tanks and their men and Pakistan’s soldiers were going deeper into Indian territory. A Muslim soldier, we were informed by people we later recognized as bigots, was equal to ten Hindu soldiers. Pakistan’s soldiers, said the naïve media and propagandists for the regime, would soon put Pakistan’s flag atop Delhi.

All of these were grave untruths, as the passage of time was to reveal. In the sky was the Bengali squadron leader, MM Alam, who downed eleven Indian jet fighters. In school, we learnt that a brave officer, Major Aziz Bhatti, had lost his life defending Lahore against an advancing Indian army. His son was in our school. He was sent off to his family with sympathy and sadness. He did not come back to school.

The perspectives are clearer now 52 years after September 1965, the emotions more sober, the realities truer and history open to more and varied interpretations. Operation Gibraltar was a ploy by Ayub Khan, Bhutto and the Pakistan army to send infiltrators – they were really Pakistani soldiers – into Kashmir in the guise of Kashmiri ‘freedom fighters’ and have Indian forces pinned down in ceaseless battles. The Pakistani establishment had little or no idea of the manner in which the Indians would retaliate. So the Indian army’s assault on Lahore came as a massive surprise to the Ayub regime. After that, it was a battle for survival and an honourable way out of the conflict for Pakistan.

The ceasefire announced on September 23 called a halt to the war. It had been a stalemate. For Pakistan in particular, it was to be the beginning of change in ways inconceivable at that point. The defenceless manner in which East Pakistan found itself during the war only hastened the demand for regional autonomy and eventual sovereignty for Bengalis. The war was a catalyst for Bhutto to expose his naked ambitions, for he would soon begin to peddle the lie of a secret clause reached by Ayub Khan and Lal Bahadur Shastri at Tashkent. The war and its aftermath were the first definitive signs of the decline of Ayub’s authority. From then on, it was downhill for the old soldier.

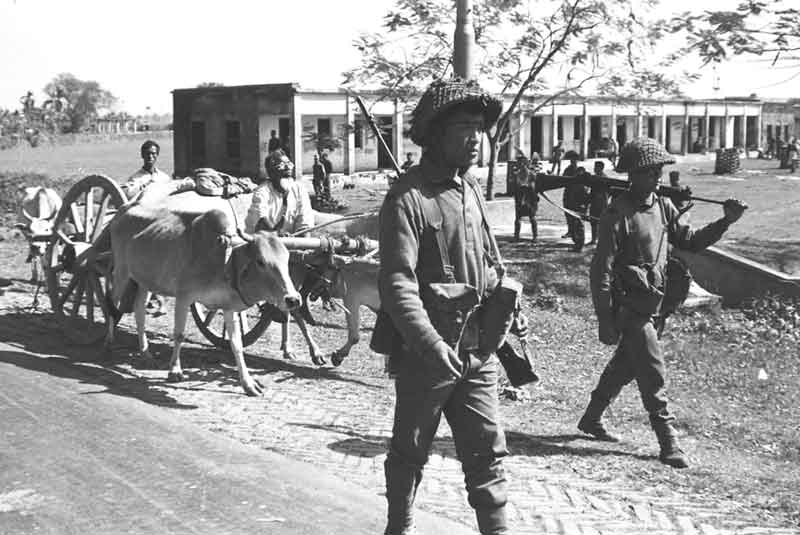

Pakistan recently observed the anniversary of the beginning of that war, September 6, as Defence and Martyrs Day. In all the celebrations of the ‘heroism’ of its soldiers, no one seems to have remembered that it had been a war that placed Pakistan at grave risk. No one has told young Pakistanis that it was a blunder. No one has acknowledged the truth that the political-military establishment in Pakistan did not learn the lessons emanating from that war. It would go on making bigger mistakes — in 1971 in Bangladesh, in 1999 in Kargil.

Ayub Khan has long been dead. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto went to the gallows in 1979. The Pakistan army killed Bengalis in occupied Bangladesh before biting the dust in 1971.

We live with the memories. More importantly, we traverse through history, the better to understand its intricate and often mysterious workings.

Courtesy: http://southasiamonitor.org/news/pakistan-has-not-learnt-the-lessons-of-1971/emerging/25092