Dramatic events in the past one year since the 2006 “April Revolution” in Nepal have been redefining the political landscape of the Himalayan nation in more ways than one. One important change is the visible rise of “marginalized” groups in national politics. The “excluded” groups – cutting across ethnic, religious and language lines – are demanding their due rights.

In the midst of these changes is the rise of the Madhesis.2 This paper attempts to assess the response of the Nepalese government towards the Madhesi uprising, the shaping of the contours of the ethnic problem in the future, and its impact on peace in Nepal up in coming days and weeks and the prospects for peace in the country. The article ends with an assessment on India’s role in Nepal.

The Madhesis

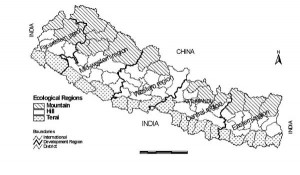

Madhesis3 are an important segment of the population in Nepal.4 They occupy economically the most significant region of the country with 70-80 per cent of the country’s industries being located in the Terai region. It accounts for 65 per cent of Nepal‘s agricultural production. Needless to say, the country’s economy depends heavily on the region. Strategically, the Terai belt constitutes the lifeline of Nepal. All the key transportation routes from India pass through this region, making it the gateway to the landlocked country. Almost all the country’s import and export takes place through this region. Given these factors, any disturbance in the region involving the Madhesis becomes extremely critical as it has the potential to seriously jeopardise the country.

With strikes, bans, and road blockades that continue to mark the unrest in Terai, economic activities have been brought to a virtual halt. Trade has been severely affected with goods worth millions of rupees stranded at border points and many manufacturing industries in Birgunj and Biratnagar shut down owing to crisis of raw materials. A recent report released by Nepal Rastra Bank, indicates that the country’s foreign trade recorded dismal performance during the first nine months of 2006/07, with 2.9 per cent fall in total exports. The report identifies the Terai unrest as one of the major factors for the poor performance of the export sector.

With strikes, bans, and road blockades that continue to mark the unrest in Terai, economic activities have been brought to a virtual halt. Trade has been severely affected with goods worth millions of rupees stranded at border points and many manufacturing industries in Birgunj and Biratnagar shut down owing to crisis of raw materials. A recent report released by Nepal Rastra Bank, indicates that the country’s foreign trade recorded dismal performance during the first nine months of 2006/07, with 2.9 per cent fall in total exports. The report identifies the Terai unrest as one of the major factors for the poor performance of the export sector.

The size of the Madhesis has been a contested issue. According to the Population Census 2001 based on mother tongue for Village Development Committees (VBCs), the Madhesis population was 6781111.5 If one were to go by this figure, the Madhesis formed 29.2 per cent of the total population of Nepal in 2001. However, Madhesi political leaders, scholars, and activists have long questioned these figures. They claim that the Madhesis form 40-50 per cent of the total population of Nepal today. For instance, Jwala Singh, leader of the Janatantrik Mukti Morcha (JTMM-Singh) has claimed that Madhesis population is 14 million.6 While the truth is difficult to establish, one can safely say that the Madhesis constitute a major chunk of Nepal’s demography.

The Unrest in Terai

Two issues need to be highlighted. First, the Madhesi issue is not a communal issue. Secondly, the Madhesi issue has not emerged in January 2007. The Madhesi question is not one of Madhesis (‘people of the plains’) vs Pahadis (‘people of the hills’). This misinterpretation of the Madhesi nomenclature by making it a community-based issue could have grave implications for the country.8 The Madhesi issue in Nepal relates to a movement against the state’s ‘discriminatory’ politics. It is a fight for recognition of rights – political, cultural as well as economic – and a struggle for equal representation and opportunity. 9

During the initial phase of violence in the Terai, the government perhaps failed to respond to the problem effectively. It was busy with other issues at hand, particularly, the peace process and the formation of government.

The current Madhesi protests began to surface in late 2006. The interim constitution became the rallying point, which the Madhesis claim, has failed to address the issues related to their rights. The trouble soon took a different turn when the country’s draft interim constitution came into effect on 15 January. Rapidly, the largely peaceful protests snowballed into widespread violent demonstrations, strikes and bans. Since then, the situation has only deteriorated. Three Madhesi outfits have been leading the agitations. The outfits are:

Madhesi Janadhikar Forum (MJF) or Madhesi Peoples’ Right Forum (MPRF) headed by Upendra Yadav. The outfit has been spearheading the ongoing Madhesi agitation in Terai. MJF’s main demands are: amendments to the interim constitution to include provisions for ethnic and regional autonomy with the right to self-determination and proportional representation based on ethnic population for the elections to Constituent Assembly (CA). Yadav has also been criticised from several quarters for his alleged ties with “palace forces”. The outfit’s student wing, Nepal Madhesi Student Front severed its allegiance in March accusing their leader of working with the “royalist” to subvert the CA elections.10 Interestingly, on April 26, the MJF submitted an application for party registration at the Election Commission and said that it will participate in the CA elections as a political party.

Janatantrik Terai Mukti Morcha (JTMM-Singh faction) led by Nagendra Paswan alias Jwala Singh. JTMM-Singh group is a breakaway faction of the Maoists that has been active mainly in Siraha and Saptari districts of Terai. The group spilt from JTMM led by Jaya Krishna Goit in mid-2006. The JTMM-Singh faction has been demanding for an autonomous and separate independent Terai state; equal participation of Madhesis in government security forces. In fact, on March 30, the outfit declared the Terai region a “Republican Free Terai State.”11 The group has been accused of fueling communal feelings between “people of hill origin” and “people of Terai region”, however, Singh reportedly claimed that his group is against the “system of unitary communal hill state power” and not people of hill origin.12

Janatantrik Terai Mukti Morcha (JTMM-Goit faction) led by Jaya Krishna Goit. Some of the conditions that the group has put forth for talks include declaring Terai an independent state, fresh delimitation of electoral constituencies based on populations, eviction of non-Terai officials and administrators from Terai region, among others. Both the JTMM groups want UN mediation in the talks. The group has been alleged of “divisive” campaign for its demand from industries to remove “people of hill origin” and replace them with Madhesi people or “people of plain origin” in eastern Terai region.13

Another outfit, Madhesi Tigers, a splinter group of the Maoists re-emerged in March after a long period of inaction. Madhesi Tigers is a splinter group of the CPN-Maoist formed a few years ago. Reportedly, its leader was killed in April 2005. According to the news reports, the Madhesi Tigers abducted eleven persons from Haripur area on March 1 but were released few days later.14 The past months have also seen emergence of new outfits. A group calling itself Terai Cobra has emerged in central Terai. Not much is known about this outfit. The first time it came out in public was on May 9, when it called a bandh in Bara, Parsa, and Rautahat districts in central Terai. Normal life was affected as markets and schools remain closed and traffic was disrupted.15 On 14 May, yet another outfit called Terai Army Dal, unheard of before, claimed responsibility of the bomb blast in Rautahat district that injured 14 people.16

Government Response

Has the government mishandled the Madhesi uprising? Arguably yes, if the worsening situation in the Terai is any indication. During the initial phase of violence in the Terai, the government perhaps failed to respond to the problem effectively. It was busy with other issues at hand, particularly, the peace process and the formation of government.17 The government’s indifference was compounded by differences between the government and the CPN-Maoist leadership (the Maoists joined the government in 1 April) over how to approach the problem. On 22 January a meeting of the eight-party alliance was called by Prime Minister GP Koirala to discuss the Terai situation. While the Prime Minister (PM) felt that the issues raised by the Madhesis and other groups can be resolved through dialogue, the CPN-Maoist chairman Prachanda and senior leader Babu Ram Bhattarai ruled out the possibility of dialogue with the Maoist splinter groups claiming that these groups were supported by “royalists elements and fundamental Hindu activists”.18

The situation in Terai remains grim with no signs of improvement. There is nothing to suggest that protests and violence will subside in the near future. Killings, strikes, demonstrations and clashes may continue.

The Prime Minister’s address to the nation on January 31 and February 7, calling upon the agitating groups for dialogue evoked mixed reactions. While the PM’s address received positive response from some groups, it failed to improve the deteriorating situation. Under intense pressure from various quarters, the government formed a committee for talks with the agitators on February 2 under Mahanth Thakur, the Minister of Agriculture. Despite this initiative, the government was increasingly coming under criticism from both within the SPA and other political parties.19 Amid growing pressure from Madhesi and other communities, the government on February 2 decided to amend the two-week old interim constitution and assured the inclusion of all communities in the organs of the state.20 However, differences among the parties delayed the PM’s second address to the February 7. The eight-party alliance voiced its collective support to the PM’s address and signed a commitment paper that they were serious about the movement in Terai and would want to resolve it by addressing the Madhesi people’s demands and aspiration.

Meanwhile, the MJF responded positively to the PM’s second address by suspending their protest programme for ten days. On the other hand, the JTMM-Goit faction criticised the PM’s address. While the JTMM-Singh faction and the MJF initially showed willingness for dialogue, the JTMM-Goit rejected talks offer saying that the government has not created conducive atmosphere for talks. Soon the MJF followed suit and on 19 February, it said it would resume agitation alleging that the government did not show seriousness. The Thakur committee’s invitation for dialogue with the agitating groups never took off. Rather more conditionalities were put before the government to start the government for the dialogue. The interminable unrest in the Terai also pushed the NSP-A to take a tougher position, even threatening to pull out of the SPA if the government did not adopt the proposal to amend the constitution before March 6.

As though the rapidly growing tension and violence was not enough, the Gaur incident, in which a clash between the MJF and the CPN-Maoist aligned Madhesi Mukti Morcha (MMM) took place on March 21, 27 people were killed and many injured, further excerbated the tension.21 Reacting to the incident the eight-party alliance in a press statement said that the government must take stern measures against such acts and safeguard life and property of the people. In the wake of the Gaur incident and in the midst of CPN-Maoists demand to ban the MJF, the government prohibited any MJF programmes.

Efforts to curb the increasing violence remained ineffective as also the invitation for dialogue remained a non-starter. In the face of the deteriorating law and order situation, the government formed the Peace and Reconstruction Ministry and appointed a new three-member committee on April 11 headed by Ram Chandra Poudel entrusted with the task to hold talks with all the protesting groups. By appointing a new ministry and a new team for talk, the government wanted to send a message that it was serious about the issues raised by the agitators. In a significant development, the MJF and the government held their first formal talks on June 1 in Janakpur. It was reported that the two sides agreed on some of the demands raised by the MJF.22 However, a final agreement is yet to be reached.

While the government expressed its concern over the continued incidents of violence and called all agitating groups for talks, the situation in many parts of Terai remained chaotic with killings, extortions and strikes marking the protests. The violence has been taken a new direction with the rise in clashes between Madhesi outfits and Maoist sister organisations. This has further complicated matters.

Prospects and Recommendations

The situation in Terai remains grim with no signs of improvement. There is nothing to suggest that protests and violence will subside in the near future. Killings, strikes, demonstrations and clashes may continue. Even as the government insists on talks with the agitating groups, there has been a reluctance to address the core Madhesi problems and demands.

The present political situation in Nepal provides all ethnic groups the opportunity to resolve their problems amicably.

In the event of any outfit entering into an agreement with the government, the level of violence may be brought down. However, so long as other groups indulge in violent activities, the situation may only worsen in the coming weeks with serious implications, given the explosive nature of the issue. And now with new outfits emerging, the complexities are only growing for the government because even if any outfit enters into dialogue with the government, the possibility of dissidents joining the new groups to carry on their violent activities cannot be ruled out.

It is feared that the situation if allowed to deteriorate further, may result into ethnic riots. However, the recent incidents indicate that the danger seems to have been averted owing to the new dimension that the violence has acquired i.e. – the Madhesi vs the Maoists, which is as dangerous.

The urgent imperative is that all the agitating groups including the Maoists must desist from violence. The first priority of the government should be to seriously address the demands of the protesters. The Madhesi groups should not forget that their real cause is political. The present political situation in Nepal provides all ethnic groups the opportunity to resolve their problems amicably. Therefore, it would be folly on the part of the Madhesis to play the spoiler. The SPA and the CPN-Maoist also need to display more maturity.

India’s Role

India has been playing a constructive role in Nepal’s political transition. On several occasions New Delhi has expressed its desire to see Nepal resolve its internal problems and move towards establishing a stable democracy. On the development front, India has been engaged in education, infrastructure, and health projects in Nepal. Since India’s shares a long porous border with Nepal’s Terai, the trouble in the region is of great concern to it.

Trade between the two countries depends on this region, as all the trading points are located there. Since violence has erupted in the Terai, India has shown serious concern over the volatile situation. Also of major concerns to India is the possiblity of the spill over of violence in Terai into India. The Indian government has been closely watching the developments in the Terai and has constantly been in touch with Nepal’s government.23

Notes:

- The assessments in this essay are based on developments till June 2007.

- Several other “marginalized” groups such as the Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities (NEFIN), am umbrella organisation of 54 indigenous and ethnic groups, the Kirats; the Tharus; the Muslims among other groups have been protesting and demand the government to address the issues of ethnic groups.

- The term Madhesi is derived from the word Madhesh meaning “mid-land” in Nepali and is defined as the lowland plains in the southern slopes of Nepal bordering Indian states of Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal and Uttaranchal. It refers to the Terai region (See Figure I). The foothill of the Chure hill is considered the dividing line between the Pahar (the hills) and the Madhesh (the plains). Hence, the people occupying the Terai belt are called Madhesis. The name is a generic term and also a topographic reference. The Madhesis include different cultural and linguistic groups – Maithili, Bhojpuri, Awadhi, Tharu, Hindi, Urdu, and other local dialects.

- There is currently a debate in the academic discourse on whether all groups in the Terai can be considered Madhesis. I have argued elsewhere that a Madhesi “identity” has came about as a result of long state “discriminatory” politics. See “Constructing Identity: The case of the Madhesis of Nepal Terai” Paper presented at Social Science Baha conference on Nepal Terai: Context and Possibilities in Kathmandu on 10-12 March 2005.

- This figure included all the mother tongues spoken in the Terai – Bhojpuri, Maithili, Awadhi, Tharu, as also Hindi, Urdu, Bangla, Rajbansi, Santhali including Punjabi and Marwari (though their share is marginal).

- See “The Himalayan Times”, January 15, 2007.

- The origin of the movement can be traced back to early 1950s. Several political parties and organisations – the Terai Congress in the 1950s; the Nepal Sadbhavna Council in the 1980s and later the Nepal Sadbhavna Party (NSP) in the 1990s – emerged at different point of time to fight for the Madhesi cause. All these organisations have fought against state’s “discriminatory” laws of citizenship and language as well as recruitment policies to the armed forces and bureaucracy. However, the problems persisted undressed under different regimes for decades. It was in this context that when the “People’s War” of the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist (CPN-Maoist) emerged in the mid-1990s some sections of the Madhesis joined the Maoists, which had promised political, economic and social rights. With this background, an attempt is made to understand the current Madhesi agitations in Nepal.

- K. Yhome, “Madhesis: A Political Force in the Making?,” Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, New Delhi, Article no. 2058, 5 July 2006

- K. Yhome, “The Madhesi Issue in Nepal”, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, New Delhi, Article no. 2228, 2 March 2007

- See “Nepal News”, March 25, 2007, http://www.nepalnews.com

- See “The Himalayan Times”, March 31, 2007.

- See “The Himalayan Times”, January 15, 2007

- See “Nepal News”, January 19, 2007, http://www.nepalnews.com

- See “Kantipur Online”, March 1, 2007, http://www.kantipuronline.com; also see “Nepal News”, March 4, 2007, http://www.nepalnews.com

- See “Nepal News”, May 10, 2007, http://nepalnews.com

- See “Kantipur Online”, May 15, 2007, www.http://www.kantipuronline.com

- A source close to the government told this author in March that the government had initially “underestimated the potential of the Madhesi uprising.” For political reasons the name of the source is keep undisclosed.

- See “Kantipur Online”, January 24, 2007, http://kantipuronline.com; also see “Nepal News”, January 23, 2007, http://www.nepalnews.com

- NSP-A on February 2 announced that it would participate only in those meetings that discuss Madhesi issues. The traditionally “royalist” party, Rashtriya Prajatankri Party (RPP) accused the government of not been serious toward the real issue of the Madhesis and that the attitude has been fueling more crises in the country. See “Nepal News”, February 3, 2007, http://www.nepalnews.com

- On February 5, top leaders of five political parties, namely the Nepali Congress (NC), CPN-Maoist, Communist Party of Nepal-United Marxist Leninist (CPN-UML), Nepali Congress-Democratic (NC-D) and NSP-A agreed on three major political issues: the interim constitution would be amended with firm commitment to a federal structure of governance in future; the election constituencies will be delineated in proportion to the population with special provision for sparely populated districts in the hill region; and to express commitment for representation of people from all castes and creed in state organ. See “Kantipur Online”, February 3 & 5, 2007, http://www.kantipuronline.com

- See “Kantipur Online”, March 21, 2007, http://www.kantipuronline.com

- See. “Nepal News”, June 2 2007. http://www.nepalnews.com

- A Nepali delegation met India’s Prime Minister and External Affairs Minister in New Delhi on January 30 where both the Indian leaders expressed their concern over the violence in Terai. Again, India’s External Affairs Minister reiterated India’s concern to a delegation of Nepali politicians when the latter called on him in New Delhi on January 31, 2007. See “The Himalayan Times”, January 31 and February 1, 2007. A Nepali delegation comprising senior leaders of the eight-political parties came to New Delhi on May 31 to held talks with Indian leaders, see http://www.nepalnews.com May 31, 2007.