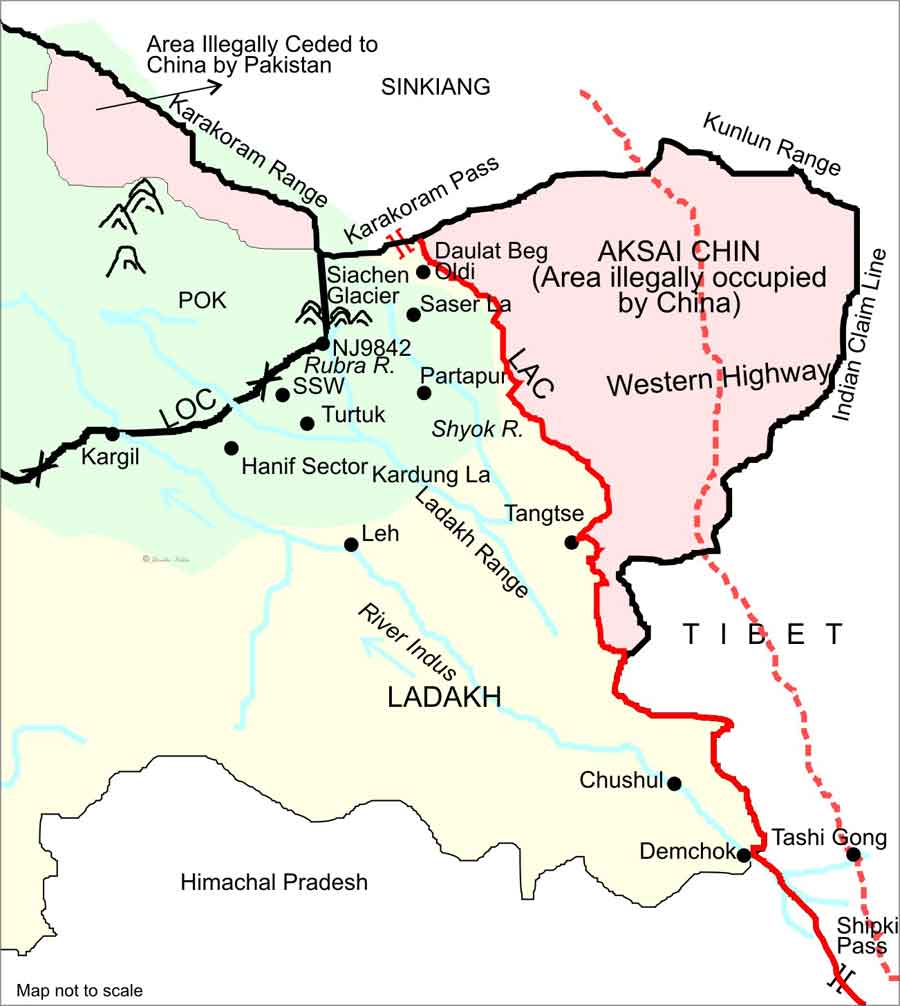

The incidents in the Depsang Plain, near the Karakoram Pass in April or more recently, in Chumar in South Ladakh, are the continuance of Nehru’s blind spot for China. There is today a huge difference of ‘perception’ on the location of the Line of Actual Control which over the years has been moving towards the South and the West. The 1959 LAC was indeed far more advantageous for India than the present LAC.

The Aksai Chin was definitely Indian territory though the area was “very remote and uninhabited”.

At the end of August 1959, a serious border incident occurred in the Subansiri sector of the then NEFA. According to a Note sent by the Indian government to its Chinese counterpart, “On August 25, 1959, a strong Chinese detachment crossed into Indian territory (in Lonju) south of Migyitun on the NEFA border and fired without notice on an Indian forward picket. They arrested the entire picket which was twelve strong but eight Indian personnel somehow managed to escape.”1

A few days later, the issue came to the Parliament. As the Migyitun/Longju skirmish was being discussed, Nehru’s Government was also asked about a road supposedly cutting through Aksai Chin in Ladakh. For the first time, Nehru conceded that China had built a road. However, he explained that although Indian maps showed the area within India’s territory, the boundary in Ladakh was not ‘defined’. He stated, “Nobody had marked it.” The Prime Minister added that Delhi was prepared to discuss specific areas ‘in dispute or as yet unsettled’, though not the ‘considerable regions’ claimed by Chinese maps.

The Aksai Chin was definitely Indian territory though the area was “Very remote and uninhabited”, said the Prime Minister who, on March 22 that year, had written to Premier Zhou En-lai on the subject. Nehru could not escape and remain vague as he had done in the past. He had to make a detailed statement; he even agreed to release a White Paper on the border issue. Nehru admitted that the boundary in Ladakh was not sufficiently defined and that Aksai Chin was a “barren uninhabited region without a vestige of grass”. He further confessed the road was, “an important connection” for the Chinese though in any case, in comparison with the NEFA, the dispute over Aksai Chin was a “minor” thing. India was, however, prepared to discuss the issue on the basis of treaties, maps, usage and geography.

Nehru admitted that the boundary in Ladakh was not sufficiently defined…

It was a real bombshell for India. The cat was out of the bag!

The New Roads

It is necessary to go back eight years since the border incident. Soon after the PLA entered Lhasa in September 1951, the Chinese decided to improve communications on The Roof of the World and built new roads on a war-footing.2 The only way to consolidate and ‘unify’ the Empire was to construct a large network of roads. The work began immediately after the arrival of the first Chinese soldiers in Lhasa. Priority was given to motorable roads – the Chamdo-Lhasa3, the Qinghai-Lhasa4 and the Tibet-Xinjiang Highway (later known as the Aksai Chin) linking Western Tibet to former Eastern Turkestan. For the latter, the first surveys were done in 1952 and construction commenced soon after5.

The official report of the 1962 China War prepared by the Indian Ministry of Defence6 gives a few examples showing that the construction of the road cutting across Indian soil on the Aksai Chin plateau of Ladakh was known to the Indian Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of External Affairs long before it was made public.

The Report quotes B.N Mullick, the then Director of the Intelligence Bureau, who claimed that he had been reporting about the road building activity of the Chinese in the area as early as November 1952. According to Mullick, the Indian Trade Agent in Gartok also reported about it in July and September 1955 as well as in August 1957.7 The different incidents which occurred in the early 1950s should have awakened the Government of India from its soporific ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai’ illusion. Alas! It was not to be so.

The different incidents occurring in the early 1950s should have awakened the Government of India from its soporific ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai’ illusion…

Instead of alarming Nehru, these disturbing reports reinforced his determination to bolster friendship with China. The first of these incidents was the harassment of the Indian Trade Agent posted in Gartok in Western Tibet. Although Nehru wrote to Zhou Enlai about it8, no follow-up action was taken and no proper analysis of Chinese motivations was made. Nehru barely brought the matter to Zhou’s notice.9

The problem of the Indian Trade Agent in Gartok, Western Tibet was without doubt linked to the work which had started on the Tibet-Xinjiang highway. Rudok, located midway between Lhasa and Kashgar, is the last small Tibetan town before entering the Aksai Chin. The presence of an Indian official nearby was embarrassing for the Chinese as they had started building a road on Indian soil. Did Nehru realize the implications of the incident over the Trade Agent or did he still believe in Chinese goodwill? It is difficult to say.

The Official report also mentions S.S Khera, the Cabinet Secretary who wrote “Information about activities of the Chinese on the Indo-Tibetan border particularly in the Aksai Chin area had begun to come in by 1952 or earlier.”10 But that was not all.

Closure of the Consulate in Kashgar

If the Indian government had been willing to read beyond the Chinese rhetoric and Zhou’s assurance of friendship, it would have seen many ominous signs. One of them was the closure of the Indian Consulate in Kashgar.

Nehru justified the Chinese actions without taking any retaliatory measures or even protesting….

Here again, as in several other cases, Nehru justified the Chinese actions without taking any retaliatory measures or even protesting. India’s interests were lost to the ‘revolutionary changes’ happening in China. He declared in the Parliament, “Some major changes have taken place there. Kashgar is important to us as a trade route. The trade went over the Karakoram, passed though Ladakh and Leh on to Kashmir. Various factors, including developments in Kashmir led to the stoppage of that trade… The result was, our Consul remained there for some time, till recently… but there is now no work to be done. So we advised him to come away and he did come away.”11

India had been trading with Central Asia and more particularly Kashgar and Yarkand for millennia. Just because ‘revolutionary changes’ had occurred in Xinjiang, the Government of India accepted the closure of its trade with Central Asia as a fait accompli. The reference to Kashmir is totally irrelevant. Since the winter of 1948, India controlled the Zoji-la Pass12 as well as Ladakh. At that time, the Karakoram Pass was still open to the caravans.

More Reports Come in

Another indication came during the negotiations for the Panchsheel Agreement. Instead of the planned three or four weeks, the talks went on for four months. One of the objections by the Chinese was the mention of Demchok as the border pass for traders between Ladakh and Western Tibet. Very cleverly, Chen, the main Chinese negotiator ‘privately’ told T.N. Kaul, his Indian counterpart, that he was objecting because they were not keen to mention the name ‘Kashmir’ as they did not wish to take sides between India and Pakistan. This argument is very odd and though Kaul could see through the game, the Indian side gave in once again.

The fact that the border post was not specified was indeed a great victory for Beijing while they were building the road in the Aksai Chin. It seems as though the Indian side was just not aware of the reality on the ground.

Chinese workers who were building the road did not have proper visas issued by Delhi on their travel documents!

Several other authors have mentioned the building of the Aksai Chin road and the fact that it was known during the mid-fifties to the Ministries of Defence and External Affairs. In his book, The Saga of Ladakh,13 Maj. Gen. Jagjit Singh said that in 1956, the Indian Military Attaché in Beijing, Brigadier S.S Mallik received information that China had started building a highway through Indian territory in the Aksai Chin area. Mallik reported the matter to Army Headquarters in New Delhi and a similar report was sent by the Indian Embassy to the Foreign Ministry.

D.R Mankekar14 provided similar information. He said that Brig. Mallik made a first reference to the road-building activities of the Chinese in a routine report to the Government as early as November 1955. Five months later, in a special report to Delhi, the Military Attaché drew pointed attention to the construction of the strategic highway through Indian territory in Aksai Chin. He also sent a copy of the report to the Army HQ.

The Official Report of the 1962 War states, “The Preliminary survey work on the planned Tibet-Sinkiang road having been completed by the mid-1950s, China started constructing a motorable road in the summer of 1955. The highway ran over 160 km across the Aksai Chin region of North-East Ladakh. It was completed in the second half of 1957. Arterial roads connecting the highway with Tibet were also laid.”

It was, therefore, known that China was building a road in the area but the government chose ‘not to upset’ Beijing.