Inter-group rivalry has a multi-dimensional impact both at strategic and tactical levels. These groups rewrite state boundaries as they attempt to control areas under different states, thus necessarily erasing physical boundaries at the strategic level. On the other hand, competition among these groups would force them to deliberately resort to criminal measures which could place a huge burden on the already existing policing mechanism. Competing priorities, escalating violence and extortion economy are the key drivers for this splinter phenomenon. A majority tribal population has also facilitated this growth which might have far reaching impact on other states with similar demographics. This would lead to a prognosis that ideological splinters among the Maoists are an archaic phenomenon replaced by splinters driven by caste and resources. Thus, the ideals once the Maoists stood for are fast relegated to the second place and into oblivion by a more powerful motivation known as money.

There are at least 16 to 18 breakaway groups operating in Jharkhand at present…

India’s Naxalite movement has always fascinated scholars and researchers alike. The Naxalite movement, that began in the 1960s under the charismatic Charu Majumdar, has been marred by internecine conflicts and fratricidal killings over a period of thirty years, with some groups integrating themselves into political mainstream while others disintegrating further, eventually forcing them to become a unified entity under the banner of Communist Party of India (Maoist) or CPI (M) in 2004.1

However, this unified entity has been again mired in splits, especially in Jharkhand. The mutations among the Maoists which is a recent phenomenon, has seldom been studied. Most of the current literature on the contemporary Maoist movement in India has been focussed on state-wise Maoist activities.2 While a body of current literature by some experts,3 has focussed more on the strategies and tactics used by the Maoists. Others have focussed on the counter measures to negate them.4

The splinters in the Naxalite movement and in the current Maoist movement in states like Jharkhand have not been studied in detail. To be able to understand the full complexity of this splinter phenomenon in the current Maoists movement, it would be necessary to have a glimpse of the splinter groups in the Naxalite movement at different points in time and draw a comparison with the various splinters in the current Maoist movement.

Splinters and Mergers

The initial chrysalis and further growth of the Naxalite movement can be segmented into three distinct phases of splits and disintegration, followed by two stages of consolidation and unification which have been listed below.5

The most prominent among the above Maoists progenies are the PLFI and the TPC…

First Phase of Splintering (1968-1973)

The seeds of the current Maoist movement were sowed by its predecessor known as “Naxalbari movement.” This was when Naxalism took shape in a village called Naxalbari in West Bengal. This movement was characterised by a collective farmers’ uprising against oppressive landlords. This popular uprising led to the formation of All India Coordination Committee of Communist Revolutionaries (AICCCR) in 1968. The principle tenets of this group were boycotting elections and waging armed struggle.

However, differences cropped up within this group concerning the concept of “annihilating of class enemies.” One group led by Kanhai Chatterjee believed that the annihilation process should be preceded by a mass agitation stage, while the majority of others in AICCCR preferred an armed revolution without mass support. This was the first fissure in the movement, and it led to the formation of Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) or CPI (ML) in May 1969, which elected Charu Majumdar as its General Secretary in 1970.

The other group, headed by Kanhai Chatterjee, started Dakshin Desh or the Maoist Communist Centre (MCC) in 1975. During this period, CPI (ML) assumed a pan-India presence which was only ephemeral. A government crackdown along with the death of Charu Majumdar in 1972 led to the disintegration of the CPI (ML).

Second Phase of Splintering (1974-1979)

This stage witnessed the creation of new entities and further splits within the Maoists. A group led by Jauhar, alias Subrata Dutt, formed the CPI (ML) Liberation in 1974, which was termed as a “course correction.” This organisation stressed on mass agitations by agrarian proletariat to encompass Marxism, Leninism and Maoism locally along with armed struggle. Organisational re-structuring and expansion began to take shape during this phase. CPI (ML) Liberation spread to Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Bihar. However, ideological differences led to further splits in this group, forming CPI (ML) (unity organisation) headed by N Prasad and CPI (ML) Peoples War Group (PWG) led by Kondapalli Seetharamiah in 1980.

The TPC was formed primarily by non-Yadavs in CPI (M) to end the dominance of the Yadavs in the Maoists…

Third Phase of Splintering (1980-1990)

The third stage is characterised by further splits due to rectification campaigns undertaken to correct past errors. Most significant among these was the embracing of mainstream politics by CPI (ML) Liberation in 1982, which registered its first electoral victory in 1989 from Arrah constituency, Bihar. This reflects a clear shift from their earlier stand against the electoral process. This created deep schisms inside CPI (ML) Liberation. During this period, the first signs of the unification process started to appear, though it was still in its infancy. An organisation known as the CPI (ML) Party Unity (PU) came into existence as the result of a merger between CPI (ML) (unity organisation) and the remnants of Charu Majumdar’s CPI (ML).

At the end of this period, the Naxalite (Maoist) movement was spearheaded by three different organisations in India. While the PWG focused on Andhra Pradesh, the CPI (ML) PU focused its activities on Bihar. However, these organisations strived to gain footholds in other regions, which forced them to reconsider bringing all the groups under a single umbrella. It was estimated that there were around 30 smaller communist groups in existence during that time.

First Phase of Unification (1990-2000)

The first phase of the unification process began in the late 1990s. Although this process was initiated as early as in 1993 between CPI (ML) PW and CPI (ML) PU, ideological differences between the two groups served to delay the process. This unified party was known as CPI (M-L) PW. Post-merger, this movement operated with its combined strength in Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and in Central India.

Second Phase of Unification (2000- till date)

The second phase was marked by the formation of CPI (Maoists) [CPI (M)] (henceforth referred to as Maoists) in 2004 by merging the MCC and the CPI (ML) PW. The formation was based on ideologies propagated by Marxists, Leninists and Maoists. This unified entity was against feudalism, imperialism and capitalism. Rejecting the earlier principle of following agrarian revolution alone, the new outfit advocated a mass revolution by the proletariat, farmers, tribals, adivasis and the backward communities in India. The most important objective of the CPI (M) was to seize political power through a protracted people’s war.

The TPC and PLFI have a hardened anti-Maoist agenda…

The Maoists started expanding their base mainly to Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh which have a sizeable tribal and adivasi population. The Maoists operated in Bihar, West Bengal, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. However, due to severe setbacks in Andhra Pradesh, the Maoists retreated into the mineral-rich states of Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, which lacked effective policing and enforcement machinery.

Firstly, this movement is certainly due to the depletion of its resources, which forced them to migrate to areas with high potential for contributing to their cause, in terms of men and money. Secondly, lack of law enforcement mechanisms in these new states also suited the Maoists. However, the Maoists movement in Jharkhand, though initially buoyant was later riddled with splits since early 2000s, leading to the emergence of progenies which started to upstage the Maoists as they grew.

Maoists Progenies in Jharkhand

There are at least 16 to 18 breakaway groups operating in Jharkhand at present. Some of the larger groups are People’s Liberation Front of India (PLFI) and Tritiya Prastuti Committee (TPC) or the Third Preparatory Committee, Jharkhand Janmukti Parishad (JJM), Bharatiya Communist Party (BCP), Jharkhand–Chhattisgarh Simanta Committee (JCSC), Jharkhand Jan Mukti Parishad (JJMP), Jharkhand Prastuti Committee (JPC), Jharkhand Sangharsha Jan Mukti Morcha (JSJMM) and Jharkhand Regional Committee (JRC).6

Inter-group clashes have also increased which has compounded the deteriorating law and order situation in Jharkhand…

The most prominent among the above Maoists progenies are the PLFI and the TPC.7 Both these have been very active in Jharkhand, acting against their parent entity as well as each other. This has led to spiralling violence levels and chaos in Jharkhand. The organisational profiles of TPC and PLFI have been briefly discussed below.

Tritiya Prastuti Committee

The TPC was formed in 2002 from MCC which later merged with CPI (ML) PW in 2004. The TPC was primarily borne out of differences among Maoists members on caste lines. Members from Bhokta, Mahto, Kherwar, Turi, Badai, Oraon, and Ghanju castes rebelled against the dominance and interference of Yadavs in the decision making process of the Maoists in Jharkhand.8

According to South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP), the TPC which initially had its stronghold in Latehar, Chatra and Palamu districts of Jharkhand gradually expanded its control in other districts of Jharkhand namely Ramgarh, West Singhbhum, Lohardagga, Simdega as well as in Gaya and Aurangabad districts in Bihar. It has presence in neighbouring West Bengal in Kolkata, Howrah and Hooghly districts. The arrest of district in-charge Rabindranath Dasgupta of TPC Kolkata, Howrah and Hooghly from Changrabandha in Mekhliganj of Cooch Behar district in West Bengal stands testimony to its presence.

It is presently headed by Brajesh Ghanju. The TPC’s organisational structure is highly hierarchical and mimics the Maoists with Zonal commands, Sub-Zonal commands and District commands at the lower end. Many open source reports estimate the current strength to be somewhere at 500 to 1500 including its ancillary members.9 Its primary source of finance is extortion and taxation from miners, contractors with an estimated annual collection of Rs 15 crore.10

The PLFI targets development projects, contractors, businessmen and industries…

People’s Liberation Front of India

Unlike the TPC, the PLFI is not a direct descendant of the Maoists. The foundation of the PLFI was laid by sibling criminals, Suresh Gope and Dinesh Gope. Suresh was killed in a shootout with the Jharkhand police during an extortion drive in 2003. However, his brother who managed to survive, wrested control of the group and named it Jharkhand Liberation Tigers (JLT) and expanded its operations, winning considerable support from the tribal populace.

However, this group was re-positioned as a Maoist splinter group after a renegade Maoist Masi Charan Purty with his followers joined the JLT, later renamed as PLFI to give a revolutionary colour to the group. Purty reorganised the PLFI on the lines of the Maoists in terms of the organisational structure. Though Purty was arrested shortly, Dinesh Gope went on to expand the network into a formidable one.

The PLFI has been wreaking havoc in Jharkhand’s Ranchi, Khunti, Simdega, Gumla, Latehar, Chatra and Palamu, although the group claims to have extended its activities and influence all over the State.11 The PLFI has its presence in some parts of Odisha and Chhattisgarh as well. The PLFI is structurally similar to the TPC with Zonal, Sub-Zonal commands and down to District commands. A 2013 survey by the Jharkhand police estimated the PLFI present strength across Jharkhand at 264 – 82 (Ranchi), 55 (Khunti), 44 (Simdega), 44 (Chatra), 17 (Gumla), 14 (Palamu), 5 (Lohardaga) and 3 (Latehar) districts.12 Though, the strength mentioned above may not appear formidable, the fact that it has managed to make an impact with such a skeletal structure, reveals that they have been intentionally ignored by the police authorities, in order to nullify the Maoists.

Discussions and Conclusion

Each of these groups has sought to establish control over vast swathes of territory in Jharkhand. This in turn has escalated the turf wars between the splinters throwing the State and the region as a whole into turmoil.

The PLFI has suffered lower casualty in police action at the same time caused higher civilian deaths…

The current phase of splintering appears to be unique and different from the earlier ones in the Naxalite movement. Throughout the history of the Maoist movement, discords among members have resulted in formation of new entities. However, the causal factors driving the current split and the objectives of the resultant off-springs seem to vary drastically from its predecessors. The third phase witnessed splinters due to political integration of CPI (ML) liberation which was a splinter group of the Charu Majumdar led CPI (ML). On the other hand, splinter groups such as Dakshin Desh (first phase) and CPI (ML) (unity organisation), CPI (ML) Peoples War Group (PWG) (second phase) of the Naxalite movement, evolved primarily due to the ideological differences with the parent entity on how to carry on the armed struggle.

As opposed to the above, the current splintering phenomenon in Jharkhand appears to be driven more by the caste factor rather than by ideological differences. The TPC which was formed primarily by non-Yadavs in CPI (M) to end the dominance of the Yadavs in the Maoists is a classic example for this. The PLFI, on the other hand, though is not influenced by caste; it appears to be controlled by criminals who are non-Maoists with the active support from renegade Maoists. The PLFI also has the support of tribals. Hence, causal factors for the splintering phenomenon in the Maoist movement in Jharkhand is more of localised issue compared to the earlier splinters which were caused by much larger and a holistic cause. This is a direct reflection of the existing social imbalance in the Jharkhand society between the backward and the non-backward classes. This existing feud has translated into creating exclusive groups among the Maoists. Given such exclusive social dimensions to the splintering phenomenon, co-existence of multiple interest groups in the same domain has increased the intensity of intra-group conflicts thus causing permanent divisions and in turn, escalating violence levels in Jharkhand.

Traditionally, splinter groups have been observed to adopt a more extreme or an incompatible position from that of its parent entity.13 A leader of splinter faction has to address this extreme cause which would appeal to the extreme thinking populace within the group and outside. In all likelihood, this would push the parent body to adopt an even more extreme modulation to thwart any breakup of its constituents. Thus, this vicious cycle of competing primacies, will eventually lead to increasing violence.

Dependence on a predatory revenue model attracts more members with criminal backgrounds, thus reducing the PLFI to nothing more than a criminal gang…

The TPC and PLFI have a hardened anti-Maoist agenda. Both the TPC and PLFI have identified the Maoists as their “principal enemy”.14 However, the violence is constituted by two variants, inter-group violence and collective violence against the common man. Non-availability of granular data with respect to the variants of violence in Jharkhand further impedes a comprehensive understanding. However, think-tanks like SATP and Institute for Conflict Management (ICM) have compiled partial data from open source reports which are helpful to this study.

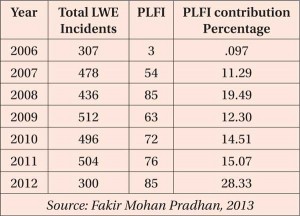

According to the Jharkhand Police, the number of violent incidents perpetrated by the Maoists and the splinter groups has been gradually rising from 2007 to 2012 (Table 1).15 However, an alarming and an increasing trend in this violence level is the contribution of the PLFI which has been growing steadily from 11 per cent in 2007 to 28 per cent in 2012 upstaging the Maoists and this trend is only growing. For instance, in the first half of 2013 alone, there were 181 incidents of LWE violence reported in Jharkhand in which 52 per cent were related to the CPI-Maoists, 29 per cent to the PLFI and 15 per cent to the TPC.16

However, the Maoists were overtaken by other factions later. Another report states that 60 per cent of the total 383 incidents in 2013 pertain to the 20-odd splinter factions.17 In 2014, the PLFI has clocked 36 per cent against the Maoists score of 34 per cent in the incidents graph. The combined violence levels of the TPC and the PLFI are gradually catching up with the Maoist levels.

On the other hand, inter-group clashes have also increased which has compounded the deteriorating law and order situation in Jharkhand. According to the ICM, from 2007 to 2013, there were at least 39 incidents of factional clashes between these groups, resulting in 74 fatalities in Jharkhand.19 These escalating levels of violence have been driven by the desire to control two key aspects i.e. territory and resources.

Most of these groups including the Maoists derive their financial resources from levies – a euphemism for “extortion”. Unlike the Maoists, the other two groups, the TPC and the PLFI, are not backed by any ideology which is the basic ingredient to be defined as a terrorist or an insurgent group. Among these two groups, the PLFI stands out as being an organisation driven purely by commercial interests.

Competing priorities, escalating violence and extortion economy are the key drivers for this splinter phenomenon.

According to Tehelka, the PLFI’s total levy extorted in 2012 is pegged at around Rs 170 crore.20 The PLFI targets development projects, contractors, businessmen and industries. According to Tehelka, a police raid on a PLFI hide-out revealed that the group procures information about upcoming projects vide Right to Information (RTIs) and uses the information to decide on the quantum of extortion from the prospective investor. The fear of extortion by these groups acts as a deterrent for new investments and projects in the state thereby directly affecting its economic development.

According to Jharkhand police, “The PLFI is purely a money minting gang with no ideology or fundamentals.”21 The actions of the PLFI stand testimony to this. In the first half of 2013, while the CPI-Maoist has been responsible for 44 fatalities (20 civilians and 24 security forces), the PLFI caused 14 fatalities (all civilians). On the other hand, the PLFI lost only one cadre against 21 Maoists cadres in police action. The PLFI has suffered lower casualty in police action at the same time caused higher civilian deaths, denoting that they have deliberately stayed away from confronting the police and combative roles but caused civilian fatalities through extortion and intimidation. Its first attempt to confront the police occurred on March 25, 2014, when it chose to attack a police party in Khunti district, surprisingly almost eight years after its inception which resulted in injuries to three policemen.

This dependence on a predatory revenue model attracts more members with criminal background, thus reducing the PLFI to nothing more than a criminal gang from the originally projected revolutionary organisation. Hence, the PLFI’s financing mode and its deliberate avoidance of confrontation with security forces prompted the Jharkhand government to mull over de-notifying the PLFI and other similar groups as criminal gangs from extremist groups. The rationale behind such a move was to project a realistic violence level which the government felt was exaggerated as it included the actions of these criminally driven splinter groups.

The current policing apparatus in India which requires a major revamp would not be able to match these groups in the long term…

While the Jharkhand government has conveniently attempted to exclude these groups from the extremist list to trim the violence levels, this may not augur well for the state. Unlike members of notified extremist group, members of criminal gangs can be prosecuted under Indian Penal Code and possibly not under counter terrorism provisions of Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA). Non application of the UAPA would render the punishment less severe. If we are to weigh this against the most of the members of these splinters groups who are hardcore former Maoists, treating them as criminals would allow them to integrate again with society which may impact the law and order situation in Jharkhand.

By de-notifying, the government would be able to show a lesser number of Left Wing related incidents. However, prudence would dictate that these are not appropriate tactics. This way, the Jharkhand government may only manage the violence levels, technically through a mere Management Information Systems (MIS). For instance, hypothetically, if the same rationale of de-notifying Maoist splinter groups is applied to insurgent groups in India’s North East, it would have disastrous consequences with policing replacing counter insurgency operations. The current policing apparatus in India which requires a major revamp would not be able to match these groups in the long term, allowing them to revive and resurrect.

Inter-group rivalry has a multi-dimensional impact both at strategic and tactical levels. These groups redefine state boundaries as they attempt to control areas under different states, thus necessarily erasing physical boundaries at the strategic level. On the other hand, competition among these groups would force them to deliberately resort to criminal measures which could place a huge burden on the already existing policing mechanism. Competing priorities, escalating violence and extortion economy are the key drivers for this splinter phenomenon. A majority tribal population has also facilitated this growth which might have far reaching impact on other states with similar demographics. This would lead to a prognosis that ideological splinters among the Maoists are an archaic phenomenon replaced by splinters driven by caste and resources.

Thus, the ideals once the Maoists stood for are fast relegated to the second place and into oblivion by a more powerful motivation known as money.

Notes

- Kujur, Rajat Kumar. “Naxal Movement of India: A Profile.” Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, 2008, accessed September 25, 2014. www.ipcs.org/pdf_file/issue/848082154RP15-Kujur-Naxal.pdf.

- E.N., Rammohan. “The Naxalite Maoist Insurgency.” Agni – Studies in International Strategic Issues, 2013, and Kujur, Rajat Kumar. “Left Extremism in India: Naxal Movement in Chhattisgarh and Orissa.”Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, 2006, accessed September 25, 2014 www.ipcs.org/pdf_file/issue/576885354IPCS-Special-Report-25.pdf.

- V.K., Ahluwalia. “Strategy and Tactics of the Indian Maoists: An Analysis.” Strategic Analysis, 36, no. 5 (2012):723-34, and Katoch, Dhruv C. “Tackling Left Wing Extremism: Current Trends and Road Map for Conflict Resolution.” CLAWS Journal, 2014.

- S.V., Raghavan, and Balasubramaniyan, V. “Containing Maoist Insurgency: An Organisational Approach.” Aakrosh – Asian Journal on Terrorism and Internal Conflicts 17, no. 63 (2014).

- V. Balasubramaniyan. “The Origins of Maoists movement in India.” Geopoliticalmonitor.com. 2013, accessed September 25, 2014http://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/the-origins-of-the-maoist-movement-in-india-4871/.

- Das, Mrinal Kanta. “The Revolution Devours Her Children.” The Outlook, August 19, 2013.

- The two of the most prominent groups which have individually upstaged the Maoists, have been discussed alone in this paper.

- Tritiya Prastuti Committee, South Asia Terrorism Portal & Nayak, Deepak Kumar. “Naxal Violence: The LWE Redux in Jharkhand.” Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies, 2013, accessed September 25, 2014, http://www.ipcs.org/article/india/naxal-violence-the-lwe-redux-in-jharkhand-3886.html.

- Nayak. “Naxal Violence: The LWE Redux in Jharkhand” & G. Vishnu. “Adivasi Warlord Kundan Pahan and Jharkhand’s Maoist Mess.” The Tehelka, December 09, 2012.

- G Vishnu. “Adivasi Warlord Kundan Pahan and Jharkhand’s Maoist Mess”

- Nayak, Deepak Kumar. “Naxal Violence: The Peoples’ Liberation Front of India (PLFI) in Jharkhand.” Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies. 2013.

- Das, no. 6

- De Mesquita, Ethan Bueno. “Terrorist Factions.”Quarterly Journal of Political Science, no. 3 (2008): 399–418.

- Das, no. 6

- Pradhan, Fakir Mohan. “Jharkhand: Rise of New Maoist Front.” The Real Politik, May, 2012, 10.

- Das, no. 6

- Edmond, Deepu Sebastian. “Shifting Balance between Maoists and Splinter Groups.” The Indian Express, April 18, 2014. Accessed September 26, 2014. http://indianexpress.com/article/india/politics/shifting-balance-between-maoists-and-splinter-groups/.

- There is no record or data for incidents related to TPC available in the open domain.

- Das. No. 6, partial data compiled by ICM.

- Majumdar,Ushinor. “Extortion in the name of Maoism.” The Tehelka, October 12, 2013.41

- Das. No. 6