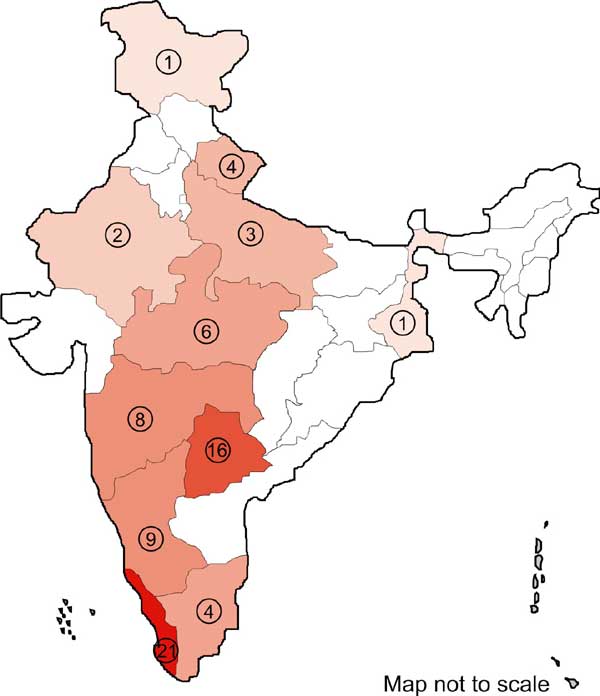

Of the 75 persons arrested, 21 were arrested from Kerala, 16 from Telangana, 9 from Karnataka, 8 from Maharashtra, 6 from Madhya Pradesh, 4 from Uttarakhand, 3 from Uttar Pradesh, 2 from Rajasthan, 4 from Tamil Nadu and one each from Jammu and Kashmir and West Bengal.

On 08 January 2020, two alleged terrorists inspired by the Islamic State1, Abdul Shameem and Y Thowfeek, shot and killed Wilson, a Special Sub Inspector of Tamil Nadu Police at Kaliyakavalai, Kanyakumari near the Kerala border. The victim was killed in an ‘execution’ style attack, shot and stabbed multiple times. Security agencies soon realized that this attack was part of a larger conspiracy to revive terrorist activities in Tamil Nadu under the Islamic State banner. Initial investigations revealed that Abdul Shameem and Y Thowfeek were part of a larger module consisting of at least 17 individuals from Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

This self-styled Islamic State module was headed by an individual named Khaja Mohideen who has been involved in several cases linked to Jihadist modules in Tamil Nadu. So were some other members of the group, who are accused in other Jihadist cases such as murder and attempt to murder of Hindu leaders in Tamil Nadu. Subsequently, some of the important members of this module namely Khaja Mohideen, Abdul Shameem, Y Thowfeek, Abdul Samad, Syed Ali Navas, Ghani alias Pitchai Ghani, Sheikh Dawood (all from Tamil Nadu) and Mehboob Pasha, Ijas Pasha (from Bangalore) were arrested by the National Investigation Agency (NIA).

The unraveling of this module appears to be the tip of the iceberg in Tamil Nadu Jihadist landscape, as closer scrutiny indicates possible merger or integration of smaller modules. Different individuals from different groups uniting under a new banner, appears to be a first of its kind in India. And more importantly, the discovery of this module also buttresses the theory of high recidivism rate among Jihadists in Tamil Nadu directly pointing fingers at the ineffective de-radicalisation programme run by the state apparatus. Studying this module briefly, would be germane to understand as to how these individuals came in touch with each other and why they would take to terrorism again.

The answers to this would enlighten us as to when and how the seeds of regrouping and possible revival of the Jihadist activities in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka were sown. Though these individuals are from different parts of Tamil Nadu and usually do not know each other well, there appears to be only two important parameters which are common that appear to have facilitated integration of these individuals into a single cohesive unit – the first one is Khaja Mohideen and the second one – prisons which has acted as the ‘think tanks’.

Prison – Incarceration or Indoctrination Facility?

The leader of the group, Khaja Mohideen, under whom, this module functioned has been involved in Jihadist activities in Tamil Nadu since 2004. Khaja Mohideen is known to be involved in Nellikuppam conversion and weapons training case in Cuddalore in 2004. He is the main accused in the murder of Hindu leader Padi Suresh in 2014 for his speech against Prophet Mohammed. Khaja Mohideen is believed to have financed and planned this murder to the last detail. Abdul Shameem and Syed Ali Navas who were accused in the SSI Wilson murder case, were also part of the module which killed Padi Suresh and were undergoing jail sentences with Khaja Mohideen.

Jail hardened Khaja Mohideen, who came out on bail in 2015, is believed to have assembled a small coterie of Muslim youngsters for performing Hijrah (religious migration) to Syria and join the Islamic State. Khaja Mohideen is one of the main accused in this case along with eight others including two returnees from Turkey who were stopped just before entering Syria. Khaja Mohideen was directly in touch with Haja Fakruddin from Parangipettai, Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu who migrated (Hijrah) to Syria from Singapore. However, before Khaja Mohideen could move any further, NIA arrested him along with some of his associates and lodged him in Puzhal jail, Chennai

The leadership of Khaja Mohideen has been instrumental in bringing together despairing members of other smaller groups under one single umbrella of the Islamic State. Khaja Mohideen, Syed Ali Navas and Abdul Shameem are accused in 2014 Padi Suresh murder case and knew each other well. The other accused in the SSI Wilson case, Y Thowfeek is accused and was in prison for the attempted murder of Tailor Murugan in Kolachal, Kanyakumari, Tamil Nadu in 2015. Thowfeek was also part of another module which had planned to kill another Hindu activist, Muthuraman in Ervadi, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu in 2016. Similarly, another accused Abdul Samad, is an accused in the Islamic State case in Chennai, where Khaja Mohideen played a key role. Another member of Khaja Mohideen group, Sheikh Dawood was part of a module called “Shahadat is our Goal” in Ramanathapuram which collected funds for facilitating the escape of Khaja Mohideen from prison.

Additionally, most of the accused appear to have been further indoctrinated only inside prisons, which have acted as ‘think tanks’ and indoctrination centres. Khaja Mohideen, who was in prison for Padi Suresh’s murder, is believed to have indoctrinated Syed Ali Navas and Abdul Shameem further into extremist ideology when they were housed inside Puzhal prison, Chennai. Another accused Y Thowfeek is believed to have been introduced to Khaja Mohideen through Syed Ali Navas when he came in touch with Syed Ali Navas and Abdul Shameem inside Nagercoil prison while they were in transit remand. Similarly, Abdul Samad came in touch with Khaja Mohideen possibly through Kuthbudeen while visiting him in prison. Kuthbudeen is also from Parangipettai, Cuddalore, Tamil Nadu which is the native place of Abdul Samad and is one of the accused in Padi Suresh murder case, closely linked to Khaja Mohideen.

Concerns and Challenges

The above highlights some major concerns and challenges for the security planners. One, there in an increase in the recidivism rates among newer members in Tamil Nadu, wherein first time Jihadi offenders have taken to terrorist activity again2. Second, groups or members of different groups appear to integrate with each other for an unjust cause under an inspiring leader such as Khaja Mohideen which has not been observed by authorities in Tamil Nadu or elsewhere in South India. Third, it also exposes chinks in the de-radicalisation, disengagement and reintegration programmes in the state.

Firstly, there has been an increased recidivism among members of Jihadist groups in Tamil Nadu where first-time offenders tend to take to terrorist activity once they are out on bail or released. Out of the 17 members who have been charge-sheeted in the SSI Wilson case, seven are from Tamil Nadu while the rest ten are from Karnataka. Out of the seven members from Tamil Nadu, Khaja Mohideen alone has hardcore extremist background, the rest were all first-time offenders who were jailed for aiding and abetting murder or attempt to murder of Hindu leaders. Additionally, almost all members of the Khaja Mohideen group, have taken to terrorist activity despite being jailed for their earlier offences. Contrary to the Tamil Nadu module, all ten members of the Karnataka module do not have any criminal antecedents nor have they been involved in terror activities before. This varied background of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka members indicate the worsening situation in Tamil Nadu.

It is evident that the prisons have become an ideal and fertile ground for recruiting/ indoctrination and brainwashing for terror groups in Tamil Nadu, where older members become enablers or leaders, while newer members who are ideologically motivated to join terrorist groups, become foot soldiers. These foot soldiers become hardcore as they are prison hardened. Given the proximity of first-time offenders with hardcore Jihadis inside prisons, it is no surprise that more and more youngsters are motivated and drawn into the Jihadi network. This transition from a sympathiser or a softcore supporter role to that of a hardcore Jihadi is facilitated by the prison ecosystem. Interestingly, if the same pattern holds good, all the ten members of the Bangalore module, make possibly take to terrorist activity in the future.

Secondly, a new phenomenon appears to have emerged from this incident wherein erstwhile members of autonomous modules appear to gravitate towards a common cause and form a new group. Members of earlier groups such as Al Ummah3 in Tamil Nadu have largely remained loyal to their group despite being banned and disbanded. Out of 200-odd Al Ummah members who were accused in the 1998 Coimbatore blasts, some 50 hardcore members alone remain in incarceration, the rest have been released. Yet, seldom there has been an instance where former Al Ummah members have joined other Jihadi outfits in Tamil Nadu. This sudden suppleness observed among present members of different groups despite ideological differences poses a security challenge as this may act as a force multiplier where members of smaller nodes easily switch sides, increasing the strength and reach of the groups. Compared to earlier Jihadist groups such as Al Ummah which was highly hierarchical, the current module appears to be more flat and less hierarchical.

Thirdly, the above two factors expose the failure of de-radicalisation, disengagement and re-integration programmes in Tamil Nadu. The high recidivism rate among the members of Jihadist groups leads one to question the efficacy of the de-radicalisation programmes. Tamil Nadu as such does not appear to have a full-fledged de-radicalisation programme for incarcerated Jihadis nor is there any clarity as to how the programme for potential Jihadis is being conducted. Available inputs indicate that the de-radicalisation programme (until recent times) for individuals who have been identified as prospective Jihadist sympathisers or followers, is conducted in a single day in Tamil Nadu and as far as Jihadis who are lodged inside various prisons are concerned, there is no programme to reform nor educate such hardcore Jihadis. Additionally, rehabilitation and reintegration programmes where hard-core members are cajoled back into the political mainstream appear to be absent.

In light of the above, some hard measures are required to be implemented to address these challenges.

Firstly, there has to be a comprehensive reformation or a de-radicalisation programme for first time offenders, both inside and outside the prisons. According to some of the first time Jihadis in Tamil Nadu, one possible explanation for them to take to terrorism again is that they do not see any future for them, once they are accused of terror-related charges. This fear is exploited and gradually moth-balled into hatred against the system and the government by recruiters inside prisons. It is believed that almost all of the new recruits from Tamil Nadu who are part of the Khaja Mohideen module, were believed to have been in distress about their future when they were in prison.

Secondly, to coerce someone to unlearn something which has been imbibed in his belief, needs time and this cannot be done overnight. The de-radicalisation process has to be a continuous one and should address the concerns on a long-term basis, both during the prison tenure and also after their release or on bail. The de-radicalisation process has to be organised to address ideological, psychological, monetary and political concerns of the members.

Thirdly, reformation or de-radicalisation programmes alone will not work till they are supported with a rehabilitation package. Since the first time offenders appear to believe that they do not have any future once they have been incarcerated for terror related charges, the onus is on the policy planners to provide a rehabilitation package so that they do not take to terrorism again. Strangely and for reasons unknown to the erudite, members of Islamic extremist groups have not been offered any rehabilitation package in India while some of the reformed members of insurgent groups such as the Maoists and North East groups have been rehabilitated.4

Fourthly, prisons have to be more segregated when housing members of terror groups. As has been brought out above, most of the indoctrination and recruitment occurs inside prisons where the senior hardcore Jihadis brainwash new Jihadi entrants and play on their fears and emotions. One possible step could be to house first-time offenders separately and not allow them to meet with hardcore leaders who act as enablers.

Lastly, prisons that act as fertile recruitment grounds for the Jihadist groups are not being monitored religiously. Mounting 24-hour surveillance on the members may help identify threats on a real time basis. Even in the case of Khaja Mohideen module, if is believed that all the members jumped bail and switched off their mobile phones. Red flags were raised when their absence was observed only when they missed their stipulated signature visits to the police stations and courts. It was too late by that time and lot of water had flowed under the bridge. Had they been kept under a 24-hour surveillance, their absence may have been noted at an earlier stage.

To conclude, the current structural and organisational changes among Jihadi groups is a new phenomenon in South India’s Jihadi landscape. These evolutions could act as a foundation for newer and meaner groups to emerge in the future which could be difficult to interdict. The counter terrorism policies that are in place, appear to have failed in either mitigating the emerging threat nor in identifying the players behind the emerging threat at the right time, despite awareness about the antecedents of the perpetrators. High recidivism rate among Jihadi groups in Tamil Nadu is cause for concern for the policy planners. Surprisingly, there is no data or study that has been commissioned to understand the reasons behind first time offenders taking to terrorism again. This lacuna has failed to address and stop the radicalisation of first-time offenders, directly being responsible for the loss of innocent lives.

Endnotes

- The members of this module have not given Bayath to the Islamic State leader in Syria. However, some unconfirmed reports suggest that the leader of the module was in touch with a key Islamic State operative. This attack was also not claimed by official mouth piece of the Islamic State Amaq News Agency, possibly indicating that this was an inspired module.

- Recidivism refers to the tendency of a criminal or a terrorist to reoffend. Almost all the members of this module, were first time offenders before this case, except Khaja Mohideen.

- Al Ummah was involved in the 1998 serial blasts at Coimbatore in which 200 members of the group have been convicted.

- There are rehabilitation schemes for surrendered members of Islamic extremist and terrorist groups in Jammu & Kashmir, but not in the other states of India.