Any General tasked to lead an expeditionary force to subjugate Afghanistan would not like to be reminded of the fate that befell the British in a similar attempt in the 19th century. Lady Elizabeth Butler’s iconic painting ‘Remnants of an Army’ depicting a half dead rider atop a struggling pony eloquently sums up the British experience. The man riding the pony was the sole survivor out of a contingent of some 4500 British troops and 12000 odd camp followers despatched by Lord Elphinston to bring the Afghans to heel. In more recent times Soviets tried it with their up-to-date weaponry.

A decade later, the empire was gone – the Afghan misadventure having contributed some final fatal blows. So history tells us that Afghanistan is not easily tamed. On the other hand as 9/11 brought home so stunningly, confluence of forces is such that Afghanistan cannot be ignored either. With an almost inexhaustible source of Jihadis incubating in the various Madrassas, and the spreading stain of Taliban control, Afghanistan could become a very deep black hole with the potential of sucking the whole world into unending chaos. So, despite the daunting prospects, and the likelihood of enormous costs in blood and treasure Afghanistan has to be rescued from going down the drain.

“¦some NATO countries may already be exploring bilateral arrangements with Iran. While big ifs undoubtedly remain in the US”“Iranian equation, given a favorable turn of events, the idea could well come alive sometimes in the foreseeable future.

Candidate Obama knew it and as President it now figures right on top of his ‘to do’ list. So as the drawdown in Iraq progresses, he plans to despatch an additional 17000 troops to Afghanistan to join the 38000 Americans already there. The hope is that an Iraq style surge would produce similar results in Afghanistan. Generals of course want more. Middle of last year, ISAF commander McNeill had indicated that instead of 60000 odd troops present in Afghanistan, NATO requires some 400000 to do the job1. Since then the situation, if anything, has got much worse. So relative to the situation, planned augmentation of forces may not be nearly enough for the mission. Even with this limited augmentation, a severe logistic challenge appears to be shaping up.

Supply Routes

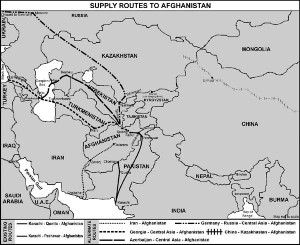

‘Geography’ they say shapes ‘history’. Perhaps nowhere is it more true than in Afghanistan. Afghanistan is a land locked mountainous country with no access to the sea. Pakistani port of Karachi is the sole funnel point for all sea borne cargo amounting to about 90 percent of all supplies destined for Afghanistan. From there the non- lethal cargo viz. food, fuel, and construction supplies, etc. is despatched via two established routes. The first route to Kandhar passes through the city of Quetta in Balochistan, winds its way to the border town of Chaman and then to Spin Boldak in Afghanistan. The second route through which nearly 75–80 percent supplies transit, leads to Peshawar in the North West Frontier Province (NWFP). From Peshawar supply convoys pass through the restive Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) to the famous Khyber Pass towards Jalalabad and Kabul.

The only other significant operational logistic base and supply route is via the Central Asian Republic of Kyrgyzstan in the North. Post 9/11 attacks, US had leased a former Soviet Air base (Manas) just outside the Kyrgyz capital Bishkek. The base serves as a major staging post facilitating transit of some 15000 men and 500 tons of cargo every month. The base is also home to large fleets of tanker aircraft used for supporting missions in Afghanistan.

The Manas arrangement is about to unravel following the failure of negotiations over US payment of lease fees. The base may close down by the middle of 2009.

The Manas arrangement is about to unravel following the failure of negotiations over US payment of lease fees. The base may close down by the middle of 2009.

Expanded Mission in Afghanistan

Depending on the rate of draw down in Iraq, US plans to deploy an additional 17000 troops in Afghanistan bringing the total strength up to 53,000. There are no officially published figures of the logistic backup required to sustain the current force level. However some informed guesses have been made.

Consider the requirement of fuel alone. Pakistan’s refining capacity can meet only half of its own requirements. Therefore, bulk of the fuel and petroleum products required for operations in Afghanistan is imported from the Gulf via Karachi. It is estimated that to meet requirements of augmented forces, some 650 to 700 additional fuel trucks will have to be put on the road. 500 to 600 more trained drivers willing to run the gauntlet in face of increasing insurgent attacks will also have to be recruited. Under normal circumstances, this may not appear like a big deal at all. But circumstances in Pakistan can hardly be called normal. The example merely serves to highlight the nature of challenges exacerbated by the insurgency in Pakistan

Vulnerability of Pakistani Routes

Reliance on just a couple of supply arteries coursing through militant and criminals infested territory naturally rendered them vulnerable and the Taliban were quick to take advantage. In March 08 a Taliban ambush destroyed 25 fuel tankers. In Nov ’08, a dozen trucks carrying ‘Humvees’ were hijacked at the Khyber Pass. Since then, supply convoys and depots in northwest Pakistan – even in Peshawar itself – have increasingly being targeted by the Afghan and Pakistani Taliban. In Feb this year militants forced closure of the road to Khyber by blowing up a 100 foot iron bridge 15 miles NW of Peshawar. The following day, a number of trucks returning from Afghanistan were torched.

Afghanistan is a land locked mountainous country with no access to the sea. Pakistani port of Karachi is the sole funnel point for all sea borne cargo amounting to about 90 percent of all supplies destined for Afghanistan.

While quantum of supplies lost to brigand activity may not be crippling in the overall context, the more serious consequence is the frightening away of contractors and drivers willing to undertake the hazardous ferrying missions. By early March this year, 130 contract drivers had been reportedly killed. In early 2008, 600 to 800 trucks used to wind their way every day from Karachi to Kabul through the Khyber Pass. Insurgent activity has brought them down to 300 to 400.

Alternative Routes

Need for finding alternatives has grown proportionately as Taliban attacks on convoys have intensified. While all neighbors of Afghanistan including Russia, China, Iran, the Central Asian Republics, and even Pakistan have a reason to worry about the consequences of state failure and thus unchecked explosion of Islamic militancy in Afghanistan, politics complicates the search for alternatives.

A cursory look at the map reveals the possible approaches to Afghanistan.

While some access routes appear farfetched at first sight, behind the scenes all options are being kept alive and hence none can be dismissed beyond the realm of possibility.

Iran

With intensification of Taliban activity, the Iran option obviously emerges in the spotlight. With completion of the Indian built strategic Zaranj–Delaram road, Iranian port at Chabahar becomes an attractive point of entry. There is an obvious convergence of US/Iranian interest in taming the Taliban and Al Qaeda, but for political reasons any US–Iranian co-operation has thus far remained a forbidden proposition.

However with President Obama’s conciliatory approach, and possible emergence of a more pragmatic leadership after the forthcoming Iranian elections, a dialogue may well get underway – particularly if some common ground could be found to the vexed issue of Iran’s nuclear programme. Indeed for both sides there are strong reasons to thaw the long frozen relationship. US needs an alternative to Karachi if it is to be in Afghanistan for the long haul. Iran needs to emerge out of its diplomatic isolation. For it to have the US or one of its allies depend on it, could become a major diplomatic asset.

In this regard there are signs that some NATO countries may already be exploring bilateral arrangements with Iran. While big ifs undoubtedly remain in the US–Iranian equation, given a favorable turn of events, the idea could well come alive sometimes in the foreseeable future.

China

The line across China also looks implausible. Yet ahead of the NATO Foreign minister’s meeting in Brussels in Mar ’09, a senior US official did acknowledge that NATO may ask China to help out by opening up a supply link for alliance forces.2

Chinese have a well established East–West railroad link from the Chinese seaboard, stretching all the way West to Xinxiang’s border with Central Asia. From Western China, presently there is just one rail connection from Urmqi into Kazakhstan which feeds into the network leading to the Afghan border. Chinese are also working on two more connectors – one each into Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan – which would enhance connectivity further.

Also read: India’s Foreign Policy: A Muddle for Sixty Two Years

The long overland transit from a Chinese port on the East China Sea to Kazakhstan and limited system capacity particularly on the Central Asian leg severely limits this route’s usefulness. Besides, even though China would like to see Afghanistan stabilize, it remains wary of US intentions in the region. Therefore, contribution of the Chinese route can only be a token – more noteworthy for its political significance than the actual tonnage hauled.

The Northern Routes

Given the difficulties of Southern and Eastern approaches, the remaining options begin at a Baltic or Black Sea port and follow some version of the following broad route outlines:-

China is investing large sums in the regions infrastructure to bring it more tightly in its orbit.

- Route 1A. Black Sea Georgian port of Poti – Baku (Azerbaijan) – transhipment across the Caspian Sea to Turkmenbashi (Turkmenistan) – Mary (Turkmenistan) – South to Afghan border North of Herat in NW Afghanistan.3 Americans are also exploring the possibility of extending this rail road link to Termez in Uzbekistan from where the cargo would be transhipped in trucks across the Amu Darya through the Salang tunnel into Afghanistan4.

- Route 1B. If transit agreements with the reclusive Turkmen regime prove problematic, Americans have an alternative across Caspian from Baku to Aktau and Beyneu in Kazakhstan – and then South East all the way to Termez through Uzbekistan.

- Route B – through Russia. To access Afghanistan from one of the Central Asian Republics to its North without costly transhipment across the Caspian Sea, traversing Russian territory is inevitable. For France and Germany a supply line along the route Germany – Moscow – Tchimkent (Southern Kazakhstan) – Tashkent (Uzbekistan) Termez (Uzbekistan) is already running. A trial run with first shipment of US military non-lethal cargo is also reportedly underway on this link.

Afghanistan has no rail system. Therefore irrespective of which Northern route is chosen, supplies will have to be switched to trucks at the Afghan-Uzbek or Afghan-Turkmen border. Facilities will have to be created to handle the anticipated traffic flow.

Quality of Infrastructure

The Northern route is planned to handle about 20 percent of the ground cargo destined for the US military in Afghanistan. This amounts to about 100 x 20-foot containers a week, compared with about 500 a week which transit through Pakistan.

During the last few years, sky rocketing oil prices had brightened Russias economics considerably. However the global downturn which has cast its shadows on all major economies of the world has not left Russia untouched. Russia needs foreign investment desperately to upgrade its decrepit infrastructure.

The state of Russian railroad system serves to highlight the typical difficulties that may be faced in utilizing the Northern routes. It is estimated that some 60 percent of Russian Railways’ fixed assets and 80 percent of cargo wagons and diesel locomotives are old and worn out. Since the Soviet days, output of freight cars has plummeted drastically. According to the Russian Railway Company’s own estimates, in lieu of 30,000 new wagons needed every year, only 5 to 8 thousand are being procured. Refurbishing the railroads infrastructure requires investment to the tune of some $380bn over the next 20 years or so.5

Similarly, robustness of the Central Asian leg of the rail network to accommodate the increase in traffic is not clear and considerable investments may be necessary to make it work.

Politics of the Northern Route

Russia has long been peeved by US (and in particular the Bush Administration) riding roughshod over its sensitivities. Eastward push of NATO, dismemberment of Serbia, recognition of Kosovo, planned deployment of ABM defences in Central Europe, engineering color revolutions in the erstwhile Soviet Republics had brought such chill in US–Russian relations as to fan speculation that the world could be on the threshold of another Cold War. With change of guard at the White House, there is a sense of thaw and it looks as if the US will pay some heed to Russian concerns.

Russia of 2009 is far more confident and appears determined to protect her vital interests. Reclaiming influence in the Central Asian region that it considers as its backyard, figures amongst its top priorities. To that end it is co-opting regimes bordering Afghanistan in the North, to limit US footprint in the region. Expulsion of American forces first from Uzbekistan and now Kyrgyzstan’s closure of the American air base at Manas are signs of Russia regaining its position of pre-eminence in the region.

During the last few years, sky rocketing oil prices had brightened Russia’s economics considerably. However the global downturn which has cast its shadows on all major economies of the world has not left Russia untouched. Russia needs foreign investment desperately to upgrade its decrepit infrastructure. With President Obama in the White House there is a change in the tenor of US foreign policy. Russia is unlikely to go so far as to shut the door on America. Therefore, while it would allow the transit of non-lethal military cargo through its territory, it will calibrate its responses carefully to leverage maximum possible mileage out of the circumstances – the extent being dependent on the degree of US need

Conclusion

Increasing vulnerability of US supply line through Pakistan is forcing the US to look for alternative routes to Afghanistan. Iran appears to be an attractive choice. However US–Iranian relations have been at such a low ebb and for such a long time that this option is unlikely in the near future. But with Americans feeling more secure in Iraq, a new administration in the White House, the situation could change.

Also read: Strategic relevance of Gilgit and Baltistan

In the absence of a Southern alternative, the US is forced to seek access from the North. One possible option could be across the Chinese Western province of Xinxiang to Kazakhstan and then to Afghanistan. China is investing large sums in the region’s infrastructure to bring it more tightly in its orbit. However as of now the long surface transit, the very difficult terrain and the attached political costs severely limit usefulness of this approach.

The other alternative is through Europe or the Black Sea. Access to Afghanistan would then entail either transhipment of cargo across the Caspian into Turkmenistan/Kazakhstan or traversing Russian territory before cutting across the Central Asian Republics. Americans appear to be exploring both approaches. Transhipment across the Caspian would incur penalty of both time and cost. Attached to the Russian route is the political cost of dependence, which the Americans viscerally abhor. The state of Russian infrastructure also doesn’t inspire confidence. However US needs a supplementary route and Russia is well aware of the American compulsions. Tempered by its need for foreign investment to repair and upgrade its decrepit infrastructure, it would try to leverage its position of advantage to extract concessions over the many thorny issues lying between itself and the Americans.

Americans could use some or several routes from the North depending on the deals that they can strike with the various states en route. However these can at best be secondary sources of supply. If the US is to persist with its Afghan mission until achievement of its objectives, it can not do without an approach from the sea – which explains the crucial centrality of Pakistan in the Afghan affair in more ways than one. This also explains why keeping Pakistan in good humour is so vital for America.

Notes

- Interview to German magazine ‘Spiegel’ reported by APP from Islamabad – Jun 01, 2008.

- NATO may ask China for support in Afghanistan – http://www3.signonsandiego.com/stories/2009/mar/02/eu-nato-afghanistan-030209/?zIndex =60793.

- Washington Post, Mar 06, 2009.

- http://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/12/washington/12military.html?_r=2&hp.

- http://www.russiaprofile.org/resources/business /russiancompanies/rzd.wbp.