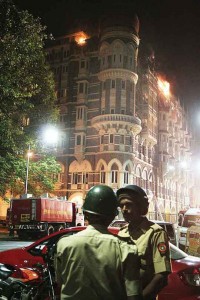

The heritage wing of the Taj Mahal Palace and Tower aflame, November 26. The Mumbai Fire Brigade evacuated hotel guests trapped inside. (Photograph: Uttam Ghosh/rediff.com)

The 2008 Mumbai attacks appear to have been a joint operation between two factions of the Lashkar that had been drifting apart due to policy disagreements. One was a ‘loyalist’ faction led by Sajid Mir; the other was a ‘dissident’ faction led by an ex-Army officer named Abdur Rehman Hashim. The latter wanted to focus on fighting Western forces in Afghanistan and possibly, extending support to Taliban groups fighting the Pakistani state. Mir, on the other hand, was a house-trained jihadist who despite his global Salafi inclinations, was ultimately prepared to defer to the India-centric agenda of his controllers. Between them, the two Lashkar commanders agreed on an operation that would strike at Western interests within the operational framework already laid out by the Lashkar leadership. The Mumbai attacks, it was hoped, would reduce tensions within the group and unite its cadres through a common sense of purpose and accomplishment.

It has been argued that the 26/11 attacks represented the externalisation of domestic militancy within Pakistan, which had drastically escalated following the Lal Masjid crisis of July 2007. During those three days in November 2008, India faced the fallout of a radical movement which it had no role in creating but which it seems destined to continue suffering from due to its geography. The country lies adjacent to a region that has traditionally been a haven for militant religious groups since the colonial era. As Charles Allen chronicles in his book ‘God’s Terrorists’, the borderlands of present-day Pakistan have long been associated with Jihadism.1 Urbanised, genteel Indians are perhaps yet to realise how close they are to this cauldron of extremist violence. Their government, however, has no excuse for underestimating the threat.

Towards A Plan

Initially, the Mumbai 2008 terror attacks were only meant to hit a conference of IT professionals that would be held annually in the Taj Mahal Palace and Tower Hotel. The original attack plan did not envisage a suicidal or fidayeen strike.

According to Charles Allen, the borderlands of present-day Pakistan have long been associated with Jihadism…

The Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT) at this point in time (early 2006) was just looking to replicate its shoot-and-scoot operation at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore carried out on December 28, 2005, by a lone gunman who killed one person before fleeing. Despite the distance between Bangalore and the international border, the gunman safely reached Pakistan within three days due to a network of logistics and support cells that the LeT had created in India over the years.2 Once in Pakistan, he bragged to the Lashkar recruits about the ease with which armed assaults could be carried out in urban India. Among his audience were those who were later on selected for the Mumbai attack. LeT switched to the fidayeen option at the very last moment, after expanding the attack plan and then realising that the gunmen may not have the option to escape from Mumbai.

Immediately after the Bangalore shooting, a Pakistani-American LeT operative named Daood Gilani was tasked to reconnoiter potential targets in India for similar strikes. To avoid arousing suspicion whilst applying for an Indian visa, Gilani legally changed his name to David Headley. Beginning September 2006, he made several trips to India, befriending locals and videotaping public buildings and strategic installations. He later told American and Indian investigators that funding for his trips was provided by a serving Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) officer named Major Iqbal. From his interrogation report, it appears that Headley was a dual-purpose intelligence asset, being jointly run by the ISI and the LeT.3 While the former used him to spy upon locations that were of military significance, the latter was more interested in tactical reconnaissance of soft targets. Interestingly, US court documents suggest that out of US $29,500 provided to Headley between July 2006 and July 2008, as funding for his reconnaissance trips to India, only $1,000 came from the LeT. The remainder was handed over directly by Major Iqbal.4

Ajmal Amir Kasab's blood-spattered shoes were left on the road at Chowpatty, after the police captured him following a shoot-out and a physical scuffle, November 26. Next to the shoes lies a spent bullet. (Photograph: Sanjay Sawant/rediff.com)

Headley’s handler within the LeT was a Pakistani national named Sajid Majeed, better known as Sajid Mir. Born in 1976, to a middle class Punjabi family in Lahore, Mir was unusual within the Lashkar in that he was an Arabised Jihadist. His family maintained business interests in Saudi Arabia and he had often travelled there during childhood. This meant that he had grown exposed to global jihadist debate that had projected the West and Israel as being permanently at war with Islam. For Mir, India was the most proximate enemy but not necessarily the most important one. He also wanted to build a name for himself in the international jihadist movement.5

In 2006, Mir had set upon attacking the annual IT conference at Mumbai’s Taj Hotel, seeing it as a way to bolster his own standing within Lashkar by attacking both Indians and Westerners with one stroke. Unlike most of his counterparts in the LeT organisation, he had no actual combat experience. An attack on Mumbai would therefore, be his coming-of-age party. His personal ambitions received a boost from events that unfolded in Pakistan and India during 2007 – 2008, which convinced the LeT leadership of the need to enlarge the Mumbai operation and strike at multiple targets.

Lal Masjid – A Silent Mutiny

In July 2007, commandos from the Pakistan Army’s Special Services Group stormed the Lal Masjid (Red Mosque) in Islamabad. Radical students based in the complex had long been attacking local businesses and creating a law and order problem in the city. After some Chinese women were abducted by these students, behind-the-scenes pressure from Beijing forced President Pervez Musharraf to order an army assault. In the resulting gunfight, several female students were killed, of whom a large percentage were the daughters of serving army personnel. In the already fraught political climate of Pakistan, the attack was perceived by many as an inexcusable act of repression by an unpopular regime.

It appears that Headley was a dual-purpose intelligence asset, being jointly run by the ISI and the LeT…

The Lal Masjid crisis is relevant to the Mumbai attacks because of its adverse impact on institutional cohesion within the Pakistani military. The deaths of soldiers’ relatives within the mosque grounds had created a groundswell of anger among the ranks. On September 13, 2007, an SSG officer carried out a suicide bombing at a military base, killing 19 of his colleagues.6 At around the same time, jihadist sympathisers in the military began providing intelligence support to Taliban factions that were attacking the Pakistani state. Incidentally, it was this militant-military nexus that UN investigators later suspected of helping to assassinate the pro-West Pakistani leader, Benazir Bhutto.7

Slain Mumbai Anti-Terrorism Squad chief Hemant Karkare's family at the Shivaji Park crematorium, November 29. (Photograph: Sanjay Sawant/rediff.com)

LeT was not immune from this trend toward fratricidal violence since its ranks included many former army personnel. Ex-commandos in particular, had long been regarded as prized assets owing to their combat skills. The LeT’s adoption of fidayeen tactics, in fact, had been driven by an ex-SSG Warrant Officer known as Abu Fahadullah. This former soldier joined the jihadists as a trainer in 1998 and was killed by Indian security forces in 2000. During his two years with the LeT, he revolutionised its operational doctrine. Having served with the SSG’s elite counter-terrorist team, Zarrar Company, he knew how conventionally-deployed military and police units would be trained to react to a terrorist attack.8 Accordingly, he devised an attack technique that left little scope for damage control, since it was focused on causing maximum death and destruction before security forces could respond effectively.

In July 2007, commandos from the Pakistan Army’s Special Services Group stormed the Lal Masjid (Red Mosque) in Islamabad.

Just as elements of the ISI had developed jihadist sympathies during the 1990s, certain ex-SSG personnel too appear to have gone through an ideological transformation. Their involvement at the tactical level of many jihadist operations led to ‘reverse indoctrination’, as strong bonds developed between trainers and their students. By 2007, these bonds had resulted in the formation of a semi-rebellious movement within the mainstream jihadist industry in Pakistan. Spearheaded by former army personnel, the movement included ex-SSG officers such as Ilyas Kashmiri and Captain Khurram. Its adherents had grown particularly disillusioned with the leaders of LeT, believing that they were too loyal to the Pakistani state, which in turn, was beholden to the Americans. A silent mutiny was brewing and this deeply worried the LeT leadership.

Pressure Builds Up

Until April 2008, the LeT had conceived of its Mumbai attack as a limited operation, focussed on a single location. However, another development in that month might have caused it to drastically expand the scope of its plans. On March 26, 2008, Indian police raided a secret meeting of jihadists in the city of Indore. Within hours, they captured many leaders of an indigenous jihadist network, which was carrying out bomb attacks across the country. Being Indian citizens, members of this network were in a position to provide their Pakistani counterparts with much-needed operational support. The arrests in Indore, a triumph of Indian counter-intelligence, suddenly deprived Lashkar of a valuable partner.

Mumbai policemen confer outside the Taj Mahal Palace and Towers, November 26. (Photograph: Uttam Ghosh/rediff.com)

Whether the idea of expanding the scale of the Mumbai attack originated with Sajid Mir, or whether it was passed down by the Lashkar leadership, shall probably never be known. What is certain is that three months after the events in Indore, in late June 2008, Mir asked Headley to conduct reconnaissance of several additional targets in Mumbai. One of these was the Chabad House (better known by its local name of Nariman House).9 The building was specifically included because it would represent an attack on Israel, which was sure to bolster the Lashkar’s standing within the global jihadist movement and bring it recruits from within Pakistan and funds from overseas donors.

Planning for the Mumbai attacks had begun in April 2008, when Headley had identified a possible landing site for the attack team. Between April and July 2008, Headley cased out other locations across Mumbai, entering their coordinates into a Global Positioning System supplied to him by Sajid Mir. He would hand over all the information gathered thus to both, Sajid Mir and Major Iqbal. From Headley’s account of these events, it appears that Major Iqbal was kept fully informed of the planning of the attacks, but apart from issuing general instructions, left the tactical micro-management to Sajid Mir.

A Convergence Of Interests

The 2008 Mumbai attacks appear to have been a joint operation between two factions of the Lashkar that had been drifting apart due to policy disagreements. One was a ‘loyalist’ faction led by Sajid Mir; the other was a ‘dissident’ faction led by an ex-army officer named Abdur Rehman Hashim. The latter wanted to focus on fighting Western forces in Afghanistan and possibly, extending support to Taliban groups fighting the Pakistani state.

The Lal Masjid crisis had had an adverse impact on institutional cohesion within the Pakistani military.

Mir, on the other hand, was a house-trained jihadist who despite his global Salafi inclinations, was ultimately prepared to defer to the India-centric agenda of his controllers. Between them, the two Lashkar commanders agreed on an operation that would strike at Western interests within the operational framework already laid out by the Lashkar leadership. The Mumbai attacks, it was hoped, would reduce tensions within the group and unite its cadres through a common sense of purpose and accomplishment.

The role of the ISI in all this appears murky. Certainly, any proposition that the ISI was ignorant of the attack plan now appears nonsensical, given the evidence subsequently provided to investigators by David Headley. However, prior knowledge of the attack does not necessarily mean that the ISI actively facilitated it at all stages with the important exception of funding Headley’s reconnaissance trips to India.

Thousands and thousands of Mumbai citizens gathered near the Gateway of India, December 1, for a protest rally in the wake of 26/11. A newly re-opened Leopold Cafe is in the background. (Photograph: Sanjay Sawant/rediff.com)

Rather, it would appear that the agency adopted a calibrated policy of ‘observation without interference’, having calculated that a Lashkar attack on India would serve Pakistani security interests admirably, in light of the Lal Masjid crisis. To quote Headley, “The ISI had no ambiguity in understanding the necessity to strike India. It essentially would serve three purposes. They are (a) controlling further split in the Kashmir-based outfits (b) providing them with a sense of achievement and (c) shifting and minimising the theatre of violence from the domestic soil of Pakistan to India.”10

Faced with an exploding security threat within Pakistani borders, the ISI had adopted an age-old counter-insurgency strategy. First identified by the French writer David Galula in his 1964 book ‘Counter-insurgency Warfare’, the strategy aimed to deflate the popular appeal of an insurgency by adopting the insurgents’ own political agenda.11 Galula had originally intended that this concept be applied within the context of the Cold War, where communist insurgents would claim that their rationale for seeking power was to improve living standards of the impoverished classes. He argued that if the government could adopt this rhetoric as its own, it could undermine the popular appeal of an insurgent group. Apparently, some individuals within the Pakistani intelligence establishment made a similar calculation during the tumultuous months following the Lal Masjid crisis.

A National Security Guard commando sprints towards the Taj Mahal Palace and Tower hotel for a better position, November 28. (Photograph: Sanjay Sawant/rediff.com)

Selective Perceptions Of Terrorism

Following the sentencing of the sole surviving Mumbai gunman Mohammad Ajmal Kasab to death in May 2010, many Pakistanis were outraged. They believed, in the words of one of Kasab’s neighbours, that jihadist attacks were not crimes if they were directed against citizens of ‘an infidel country like India’.12 Such views might be extreme but research has suggested that they are not confined only to a lunatic fringe. A 2010 study by American scholars found that many Pakistanis define ‘terrorism’ in terms of the victims’ identity not the methods used. A bomb attack upon other Pakistanis is by definition, a terrorist attack but an attack upon a foreign target might not be. On an average, the study found that popular support for jihadist strikes on Indian civilians is three times higher than support for similar strikes carried out within Pakistan itself.13

The Indore arrests, a triumph of Indian counter-intelligence, suddenly deprived Lashkar of a valuable partner.

Selective views of terrorism are not unique to Pakistan. The United States, long thought to be a ‘natural ally’ of India in the fight against jihadism, has reportedly been compartmentalising its counter-terrorist efforts as a matter of course. According to a top-ranking Indian official, the US did not arrest David Headley in October 2009 because it suddenly became aware of his involvement in the Mumbai conspiracy. Rather, this official insists that the arrest was a form of ‘protective custody’, intended to silence Headley before he fell into the hands of Indian intelligence. Ever since the Mumbai attacks, Indian investigators had been scrutinising international travel records, seeking to identify who had carried out the advance reconnaissance for LeT. They suspected a New York connection and soon narrowed down their search to a handful of individuals. Then, in what is believed to have been a major error of judgment, the Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW) briefed the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) about the progress of its investigation.

The role of the Inter Services Intelligence in all this appears murky…

Realising that the Indians were closing in on Headley, the CIA had him picked up. At the time of his arrest, R&AW was allegedly two months away from definitively identifying Headley as the spy who had cased out the Mumbai 2008 targets. If this account of events is accurate (and it is virtually impossible to obtain independent verification) then the CIA was running Headley as an intelligence asset within the LeT as late as 2008 – 2009.

The Way Forward

India stands alone in its fight against Pakistan-based jihadist groups. International expressions of support in the aftermath of terrorist attacks mean nothing. They are as devoid of substance as the condolences that invariably accompany them. In the final analysis, India has been cast out as ‘a sacrificial lamb’ to quench the bloodlust of a jihadist machine that nobody else has the courage or inclination to extirpate. Indian security experts should accordingly acknowledge that diplomatic initiatives have outlived their usefulness. What is needed is a more proactive stance, to be covertly implemented at the operational level by relevant components of the intelligence community and the military.

Notes

- Charles Allen, God’s Terrorists: The Wahhabi Cult and the Hidden Roots of Modern Jihad (London: Little, Brown, 2007).

- ‘LeT financier confesses to role in Mumbai terror attacks’, Economic Times, 21 December 2008, accessed online at http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2008-12-21/news/28474893_1_mumbai-terror-attacks-sabauddin-iisc-campus, on 16th December 2011.

- Interrogation Report of David Coleman Headley (complied by the National Investigation Agency), p. 58 and p. 66.

- See charge sheet filed by US prosecutors, United States of America versus Ilyas Kashmiri, Abdur Rehman Hashim Syed, Sajid Mir, Abu Qahafa, Mazhar Iqbal, FNU LNU aka Major Iqbal and Tawahhur Hussain Rana (Second Indictment), pp. 5-10, accessed online at http://www.justice.gov/usao/iln/pr/chicago/2011/pr0425_01a.pdf, on 16 December 2011.

- Praveen Swami, ‘Sajid Mir’s War Against the World’, The Hindu, 30th May 2011, accessed online at http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/article2062894.ece, on 16th December 2011.

- B. Raman, ‘Pashtun Army Officer Kills 19 SSG Officers’ International Terrorism Monitor, Paper No. 279, South Asia Analysis Group, accessed online at http://www.saag.org/common/uploaded_files/paper2371.html, on 14 December 2011.

- Report of the United Nations Commission of Inquiry into the facts and circumstances of the assassination of former Pakistani Prime Minister Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto, pp. 50-53, accessed online at http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/Pakistan/UN_Bhutto_Report_15April2010.pdf, on 16 December 2011.

- Syed Saleem Shahzad, Inside Al Qaeda and the Taliban (London: Pluto Press, 2011), pp. 82-83.

- Interrogation Report of David Coleman Headley (complied by the National Investigation Agency), p. 73.

- Ibid, p. 61.

- David Galula, Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice (Wesport, Connecticut: Praeger Security International, 1964).

- Waqar Hussain, ‘Pakistan home village calls for Mumbai suspect’s release’, Hindustan Times, 3rd May 2010, accessed online at http://www.hindustantimes.com/News-Feed/News/Pakistan-home-village-calls-for-Mumbai-suspect-s-release/Article1-538751.aspx, on 16th December 2011.

- Karl Kaltenthaler, William J. Miller, Stephen Ceccoli and Ron Gelleny, ‘The Sources of Pakistani Attitudes toward Religiously Motivated Terrorism’, Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, Vol. 33, No. 9 (2010), p. 823.