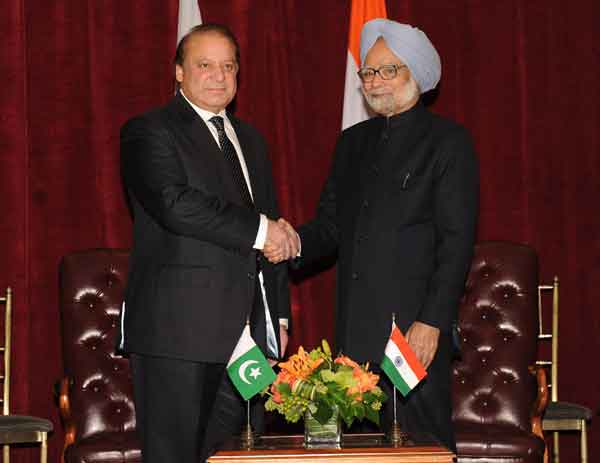

The Prime Minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh in a bilateral meeting with the Prime Minister of Pakistan, Mr. Nawaz Sharif, in New York.

India’s search for a successful neighbourhood policy continues. Sections of our society are anxious about our failure to manage our relations with neighbours properly. We tend to blame ourselves for the unsatisfactory state of relations within South Asia, believing that being by far the biggest country we bear the biggest responsibility.

…India’s neighbourhood policies are faulty because governments have lacked vision about managing the country’s periphery.

I.K. Gujral wanted to craft an approach that would modify India’s image from a regional hegemon to one of an accommodating neighbour acting generously, without expectations of reciprocity. A year after his passing away, one can reflect on the practicality of such a policy. In September, 1996, as foreign minister, Gujral outlined in a speech in London the five basic principles that would govern the neighbourhood policy of the United Front government, of which he was a member: First, with Nepal, Bangladesh, the Maldives and Sri Lanka, India does not ask for reciprocity but gives all that it can in good faith and trust. Second, no South Asian country will allow its territory to be used against the interest of another country of the region. Third, none will interfere in the internal affairs of another. Fourth, all South Asian countries must respect one another’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. And fifth, they will settle all their disputes through peaceful bilateral negotiations. Reiterated by him in another speech in Colombo in January, 1997, these principles came to be described later as the Gujral Doctrine.

How these five principles could be called a doctrine governing Indian policies is unclear, as four are presented as norms of conduct for all South Asian countries, and, given the context, for Pakistan in particular. Besides, respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, non-interference in internal affairs of countries, peaceful settlement of bilateral disputes and not permitting one’s territory for activities against the interests of other states are standard principles governing international relations. The Indian journalist who packaged all these principles as the Gujral Doctrine was indulging in diplomatic excess.

But Gujral’s first principle does constitute a major break with conventional diplomatic thinking. Contrary to the well-accepted principle of reciprocity governing international relations, he talked of non-reciprocal Indian concessions to Nepal, Bangladesh, the Maldives and Sri Lanka. This appeared to be calculated generosity towards select neighbours who, because the relationship with them was not fundamentally adversarial, could be drawn more firmly into the Indian orbit, limiting the scope for unfriendly external powers to manipulate prevailing anti-Indian lobbies there against our interests. A degree of hard thinking behind this proposition of non-reciprocity explains Pakistan’s absence from it. Non-reciprocity with Pakistan in select areas could have been considered, too, as part of efforts to build goodwill with sections of Pakistan’s public in favour of improved relations with India, even if in 1996 Pakistan’s involvement in terrorism was at peak levels.

If India is tough with its smaller neighbours, it opens itself to accusations of hegemony. If it is indulgent, it presents a picture of weakness and indecisiveness that encourages a disregard of its own sensitivities and interests.

If, in spite of the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks and other provocations from Pakistan, lobbies in India can continue to advocate unilateral gestures of goodwill towards Pakistan, whether on trade or visa issues, Gujral could well have included Pakistan — our biggest problem — in his non-reciprocal matrix. But he did not. Gujral has explained in his autobiography that as we had to face two hostile neighbours in the north and the west, we had to be at “total peace” with all other immediate neighbours in order to contain Pakistan’s and China’s influence in the region. Curiously, Bhutan is absent from his list of countries entitled to non-reciprocal gestures by India.

In practical terms the Gujral Doctrine produced little overall, although the 1996 agreement on sharing the Ganga waters was undoubtedly significant. Notwithstanding the exclusion of Pakistan from the non-reciprocal policy framework, India did unilaterally announce, in 1997, some concessions to a category of Pakistani tourists with regard to visa fees and police reporting. India agreed to a composite dialogue with Pakistan in 1997, but that was an exercise in conventional diplomacy rather than a unilateral concession by India. Pakistan violates, till today, four of the five principles of the Gujral Doctrine, and, until recently, Bangladesh too was violating one of them.

The Gujral Doctrine was a product of that incessant search by our political class for the best way to manage our neighbourhood. If non-reciprocity is no longer part of our governmental discourse, even though lobbies continue to propose unilateral concessions to our neighbours, including Pakistan, it is a reminder of the complex challenges India faces in dealing with its periphery with the right mix of policies which preserve the essential interests of all. Enlarging areas of understanding, reducing points of conflict, fortifying mutual trust and confidence, building rapport at the leadership level and earning people’s goodwill would be obvious policy goals. But these are very difficult to achieve practically because huge disparities in size and power, nationalist sentiments, identity issues, religious forces and the role of external powers complicate the search for balanced equations.

If India is tough with its smaller neighbours, it opens itself to accusations of hegemony. If it is indulgent, it presents a picture of weakness and indecisiveness that encourages a disregard of its own sensitivities and interests. There is no mathematical formula for an optimal mix of self-assertion and accommodation that can be applied with success. We may be a big power in relation to our neighbours and believe that we can have our way with them. But our neighbours can reach out to even more powerful countries in the neighbourhood and beyond in order to balance our weight. Just as other big powers do not have a free hand in their neighbourhood, there are limits to what India can do to impose its will on its neighbours. America’s problems with Cuba or Venezuela, those of Russia with the erstwhile constituents of the Soviet Union, and China’s tensions with east and southeast Asian countries should dispel any simplistic analysis about India’s policy failures in its neighbourhood.

The Gujral Doctrine drew from the enduring belief that India’s neighbourhood policies are faulty because governments have lacked vision about managing the country’s periphery. Our policies may be deficient in some respects, with mounting differences between the Centre and the states on foreign policy aggravating matters. But that India has the power to shape its immediate environment with supposedly more enlightened polices and that the principal blame is on us if we have neighbourhood problems are questionable assumptions.

Despite evidence to the contrary, some vocal lobbies still accept the premise that more generosity towards neighbours, especially in the economic domain, would win returns that have escaped us all this while. Beyond all this, there is the over-arching belief that for India to rise globally it must first ensure peace and security in its own neighbourhood. Actually, we need to be less romantic about the rewards of generosity, less guilty about our supposed failings and more self-confident about our capacity to rise even with the burden of our neighbourhood.