Energy security and security of energy conjoined with international trade have become the cornerstone of trade pacts, alliances and military coalitions in the present era. Bilateral agreements, multilateral coalitions, Free Trade Agreements, Most Favoured Nation (MFN) status etc., have become order of the day. The pace at which these deals are either made or broken indicate that the established world order is undergoing radical and swift changes. Aligning and coping with these changes whilst maintaining a strong focus on national interest, foreign policy and diplomacy have become the need of the hour.

The waning of American influence in world affairs and increased economic footprints of China across the globe indicate a perceptible shift in world order. India has so far treaded astutely and marched cautiously in the global conundrum, improving its credentials and say in global affairs. Among the various Indian investments across the globe, few purely economical and few geo-strategic, India’s investments in the Chabahar port of Iran needs introspection.

China, in its attempts to secure Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs) and energy security, has shown foresight in managing its Malacca Dilemma through String of Pearls, by adding firepower to its military and increasing size and endurance of its fleet by modernisation of PLAN.

The Malacca Dilemma

The Malacca Dilemma refers to China’s predicament and fear on security of energy due to the Malacca Straits that it has to traverse. China’s reliance on oil imports from the Gulf to power its growth, which passes through the Indian Ocean has made its dependence on the Malacca Straits more pronounced. China feared that in any conflict it could be choked in the Straits of Malacca in two ways: Firstly, the imported oil and raw materials that passes through the straits could be choked by USA, India and its allies. Secondly, it could be militarily checkmated by India in the Malacca Straits curtailing ‘its interests’ in the Indian Ocean. China with its geo-strategic vision and hegemonic aspiration decided to overcome this dilemma by finding alternate land routes for trade. How China’s Belt and Road Initiative, connecting the huge and populous land masses of Asia, Europe and South East Asian nations would propel its trade is open source and needs no further deliberation.

The growth of China militarily and economically has been astounding in the last two decades. When the world crumbled economically, due to natural calamities and man-made economic disasters of great magnitude, Chinese economy grew and marched ahead. When ‘few nations’ closed their doors for investments, China invested aggressively across the globe. When ‘few nations’ feared and withdrew from China, it moved ahead and made alliances with select others. All that the world could do is wait, with bated breath that somehow, someone, somewhere would pull the chains against China’s march forward.

China grew militarily: first by modernising its military, secondly by adding on to its firepower and thirdly by restructuring its armed forces. The military might and expansion of its fleet led it to venture out into unchartered waters without fear. The dramatic entry of Chinese taskforce, two guided missile destroyers and a supply ship, into the Indian Ocean in Dec 2008 for anti-piracy patrols and the continuous presence of Chinese warships in the IOR have altered the power equations. Today on an average, there are 7-10 Chinese warships and few Research Vessels in the Indian Ocean at any given point of time.

In addition, China has secured its energy lines through various agreements in its near and far neighbourhood. It has astutely invested in ports and port infrastructure across the globe especially in the IOR as part of the 21st century Maritime Silk Route (MSR) under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Its investments in the Kyaukphu port of Myanmar connecting Kyaukphu to the Yunnan province and in the Gwadar port of Pakistan connecting Gwadar to the restive Xinjiang province are strategically planned to reduce dependence on sea routes. It is needless to deliberate on the time, cost and energy saved in transportation of cargo from and across the Indian Ocean to mainland China.

It could be safely presumed that China has acquired the ability to escort its cargo from the Cape of Good Hope and the Gulf of Aden to China through the Malacca, Sunda and Lombok Straits and vice versa. It has also acquired the capacity to transport the cargo to mainland China through any of these ports mentioned.

Would it be appropriate to surmise that China has overcome its Malacca Dilemma decisively? Though one could take consolation in the belief that China doesn’t have power to change the narrative in the Indian Ocean, that it has formidable force levels and tie-ups to escort and operationally turn-around its fleet in the IOR are irrefutable.

India’s Trade with Central Asia

Against this background, it is important to see how India has fared in the last two decades, especially in trade with Central Asia, its immediate neighbourhood. India has also grown military and economically over the years. In its growth, it has risen as a responsible nuclear power, a robust democracy and a net security provider in the IOR capable of providing required assistance to its neighbours. Its growth is considered benign by one and all, apart from its western neighbour. It has fared well in most of the global indices and is seen as a champion particularly in the fight against terrorism and climate change. However, the goodwill it garnered has not translated much into business deals and agreements.

While India’s ‘Look East’ and ‘Act East’ policies have translated the vision into tangible deals, its attempts to engage with Central Asia through ‘Connect Central Asia Policy’ (2012) have been fraught with inconsistencies, inadequacies and has not yielded much results. A cursory look at the major energy-security related projects with Central Asia is essential at this juncture.

Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) Pipeline

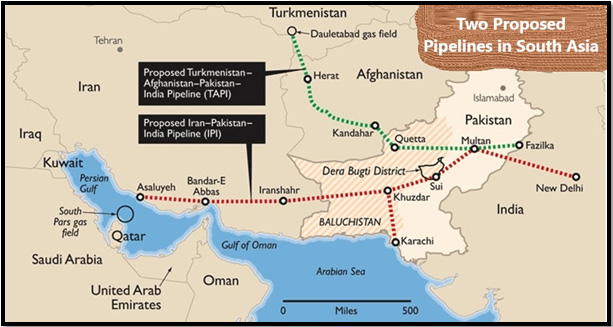

TAPI Pipeline (a 1,814 kms long pipeline running 214 Kms in Turkmenistan, 774 Kms in Afghanistan and 826 Kms in Pakistan) was conceived as a trans-country natural gas pipeline originating from the Galkynysh gas field of Turkmenistan, traversing Afghanistan through Kandhar and Herat, Pakistan through Quetta and Multan and terminating at Fazilka in Punjab, India. The plan for TAPI was conceived as early as 1990s, initially with three countries and India was invited to join in 2003. Despite signing of the Inter-Governmental Agreement in 2010 and bilateral Gas Sale Agreements in 2013 with a target to pump gas by 2019, the project has languished due to various factors ranging from political instability to lack of political will, predominantly in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Asian Development Bank (ADB) has mentioned the Indicative Implementation Period of Phase 1 as Oct 2021 – Sep 2024 and completion in Sep 2024[1]. India’s reluctance in the Project due to the political instability in Afghanistan and inimical Pakistan has been accentuated “with Taliban slated to now become a recognised stakeholder in Afghan politics…..”[2].

Source: http://outlookafghanistan.net/topics.php?post_id=2209 (Edited)

Iran-Pakistan-India Pipeline (IPI)

Another project of significance is the Iran-Pakistan-India (IPI) pipeline. Conceived as a 2,670 kms long pipeline (running 1,115 Kms in Iran, 705 kms in Pakistan and 850 kms in India) with a proposed investment of US $ 7 billion[3] in 2006, the project came under pressure during the negotiations of the US-India Nuclear Deal. The genesis of the pipeline dates back to the 1990s with Pakistan-Iran signing an agreement for a natural gas pipeline in 1995 and Iran-India signing one in 1993.

The project has not fructified even after two decades indicates that the project may not see the light of the day for India. Meanwhile China has been keen to take delivery of gas from Pakistan through the proposed IPI. Iran and Pakistan are in agreement since Iran will sell gas and Pakistan will get its transit fee. Tehran has already built its part of the pipeline linking South Pars gas fields to the Pakistani city of Nawabshah and Beijing started work on the section of the pipeline between Nawabshah and the port of Gwadar as part of CPEC[4].

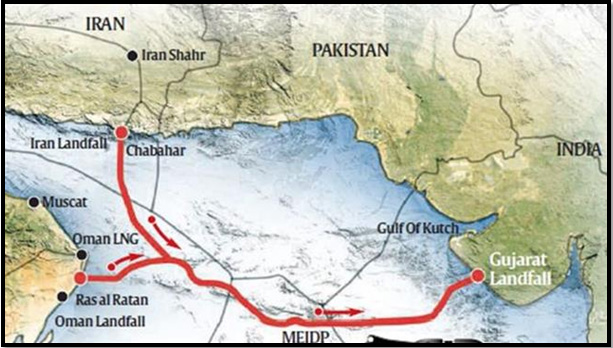

The Middle East to India Deepwater Gas Pipeline (MEIDP)

The lack of progress on offshore pipelines due to various geo-political factors made India look for deepsea options to transfer gas. Discovery of gas deposits at Farzab B in the Farsi block in Iran by a consortium led by Indian ONGC Videsh Ltd (OVL) in 2008 has led to another engagement with Iran for development, extraction and transportation of gas to India[5]. A bilateral agreement with Iran to shift the gas to India via sea through the Oman-Iran-India Pipeline or the Middle East to India Deepwater Natural Gas Pipeline (MEIDP) is on the drawing board. The proposal was to export gas from Ras al Jafan in Oman and Chabahar in Iran to Porbandar in Gujarat and connect it to the national gas grid. The pipeline is proposed at an indicative cost of US $ 5.2 billion and would traverse approximately 1300kms.The technical studies carried out by few companies including Engineers India Ltd (EIL) of India have concluded the project feasible.

Source: https://en.irna.ir/news/82003819/India-set-to-sign-agreement-with-Iran-for-undersea-gas-pipeline#gallery

International North South Transport Corridor (INSTC)

India’s attempts to establish trade links through alternate routes has led to investments in the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) and Chabahar Port. INSTC, spanning over 7,200 kms, is a multi-modal transportation plan established in Sep 2000 at St. Petersburg by Iran, Russia and India for the purpose of promoting transportation cooperation among member states. The corridor connects Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea through Iran and further connects Russia and North Europe. The INSTC was expanded to include eleven more members subsequently.

From Mumbai, the southern hub, INSTC extends through sea to Bandar Abbas (Iran), which occupies a strategic position in the Strait of Hormuz. From there, it extends by road to Bandar-e-Anzali, another Iranian port on the Caspian Sea. Further, the route extends to Astrakhan across the Caspian Sea and then the goods are to be taken to other regions of Russia and Europe by Russian Railways.

Source: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/indias-eurasian-push-bri-versus-international-transport-singh

India’s Investments in the Chabahar Port

The projects involving Iran, either offshore or over land, have been subjected to political vagaries and sanctions that have strangulated Iran. They are also affected by political instability within the transit nations and have not seen the needed traction till date. Afghanistan and Pakistan stood to gain as transit routes (due to transit fee) in the land-based gas pipelines. For India, the only opportunity available is the MEIDP, a project in its nascent stage but seemingly feasible despite technical difficulties.

With connectivity over land for trade towards Central Asia seemingly closed, India’s attempts to gain access to Central Asia through Afghanistan bypassing Pakistan through Chabahar is a bold move. India signed a trilateral agreement with Iran and Afghanistan in May 2016 to develop Chabahar Port connecting India, Iran and Afghanistan. India issued a credit line of $150 million through Exim Bank in 2016. The Government of India took over operations of a part of Shahid Beheshti Port, Chabahar in Dec 2018. With the inauguration of India Ports Global Chabahar Free Zone (IPGCFZ) at Chabahar in Dec 2018 commercial operations began. India’s allocation of Rs 100 crores in the 2020 budget shows India’s interest and commitment in Chabahar.

India’s Chabahar Dilemma

Though Chabahar will help India to increase its trade with Central Asia, it is to be remembered that Chabahar Port is open to investment from all nations. The euphoria of India’s geo-political success has been countered by the news of proposed economic and security-strategic partnership deal between China and Iran in Jul 2020 wherein China intends to invest US$400 billion in Iran. As and when sealed, “the deal will fundamentally change Iran’s relationship with China. It will put Tehran in Beijing’s corner and India could see its influence diminish overtime”[6].

The changing contour merits serious attention and consideration on India’s investment in the Chabahar. No doubts, it opens the trade route to Afghanistan, CAR and Eurasia which is extremely important and has high growth potential. But is India landing in a Chabahar Dilemma similar to that of the Malacca Dilemma of China?

China’s sole aim was to reduce its dependence on sea routes for trade and overcome the threat posed by a maritime chokepoint. It overcame this dilemma by identification and creation of alternate land routes and ports. India’s attempts to reach Chabahar port for trade with Central Asia is fraught with the same dangers at sea, albeit sans a maritime chokepoint.

With China controlling the Gwadar Port in Makaran Coast and firmly based at Djibouti in the Horn of Africa, and its proposed investments in the Chabahar Port in the Persian Gulf, (though one can argue that Gwadar and Chabahar will not be used for military purposes), Chinese military footprint is on the increase. With Gwadar and Kyaphku serving as entry and exit trading ports, Chinese naval footprint is bound to go up manifold in the IOR.

India’s cargo could be monitored and threatened enroute its passage to Chabahar by inimical entities or during war. In a hostile situation, a trade warfare could not be ruled out. With India’s present control over the IO, India has the wherewithal to escort and protect its trade. However, India will have to divert its naval war resources for trade protection.

Increasing investments in Chabahar in search of alternate trade route to Central Asia will certainly entangle India into a ‘Chabahar Dilemma’. The MEIDP, as and when it fructifies would meet India’s need for natural gas. Similar offshore pipelines may meet the requirements of oil. But for trade in commodities with Central Asia, India definitely needs a land route.

India traded with Central Asia and Eurasia through land routes across Afghanistan and Tajikistan. With Pakistan occupying and controlling parts of Kashmir, India could not increase its investment and trade with Central Asia. The Indian landmass occupied by Pakistan is critical and crucial being the only land connectivity to the CAR through Afghanistan.

Location of POK is geo-strategic since it shares borders with three neighbours: Punjab and North-West Frontier Provinces (presently Khyber-Pakhthunkhwa) in the West, Wakhan Corridor of Afghanistan in the North West and Xinjiang province of the People’s Republic of China to the North. China is connected to Pakistan through POK in its BRI land route -the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Without this connectivity through POK, CPEC would cease to exist.

China and Pakistan are equally alarmed by the decisive action of the Govt of India in reorganising the state of J&K into two Union Territories in Oct 2019. Pakistan is concerned about the future of POK and about the Chinese investments. China is concerned about the connectivity to Gwadar through CPEC.

India’s legitimate sovereignty concerns over POK is pending resolution for long. India has to take decisive action on POK since it impinges on India’s sovereignty and impacts its trade, growth and energy security. It is time to take actions to ward off the ‘Chabahar Dilemma’ that India seems to be landing into.

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are the personal views of the author and don’t represent the official policy of the Government of India/ Indian Navy.

—————————-

[1]“Proposed Loan, Grant, Partial Credit Guarantee, and Transaction Technical AssistanceTurkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) Gas Pipeline Project (Phase 1)”, ABD Concept Paper, Project No : 52167-001, Jun 2020, P 6.

[2]SanketSudhir Kulkarni, “US-Taliban Talks and the Fate of TAPI Pipeline”, Raisina Debates, Observer Research Foundation, March 29, 2019.

[3]Abbas Maleki, “Iran-Pakistan-India Pipeline: Is it a Peace Pipeline”, MIT Centre for International Studies, 07-16 Sep 2007.

[4] Guillaume Lavallee,“Iran Deal Fuels Tussle for Gas Pipelines in Pakistan”, AFP, July 23, 2015, accessed on September 10, 2020, https://news.yahoo.com/iran-deal-fuels-tussle-gas-pipelines-pakistan-063355758–finance.html

[5]“The Middle East to India Deepwater Gas Pipeline – A Favourable Situation For All”, The Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India, August 2017, P 7.

[6] “As China Eyes Multi-billion Dollar Iran Deal, India’s Chabahar Port May Lose Relevance”, WION, New Delhi, July 13, 2020, accessed on September 10, 2020, https://www.wionews.com/india-news/as-china-eyes-multi-billion-dollar-iran-deal-indias-chabahar-port-may-lose-relevance-313054

Nice article and explained very well.

?

Nice Article and well drawn conclusions

Interesting Research Article…

Nice article… comprehensive

Well written and great to see the clarity of thought.

Well written & Impartial article seeing after a long time!

Since 1947, India’s foreign policy is “ROLLER COASTER”!

FULL CREDIT GOES TO WRITER!

JAI HIND!

A very informative article.

Great work sir ……

Jai hind

So informative and is in layman’s terms…….great work sir…..

‘India has so far treaded astutely’

Our policy of late has been anything but astute.

That said, the author’s conclusion regarding POK is correct: in fact, I would go much further.

He also deserves praise for highlighting the Chabahar dilemma.

Overall, a good, informative paper.

Thank u sir for this lucid and simple analysis. All aspects were prudently

and deftly covered in short , found it very interseting to read .. need more articles authored by erudite like you.