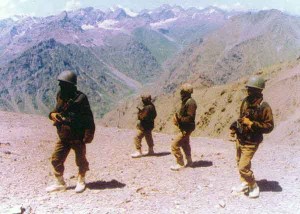

It is only ten years since the Kargil War, and it has already faded from public memory. ‘Tiger Hill’, ‘Tololing”, “Pt 5140”, Mushkoh Valley, and Muntho Dhalo are remembered only in Indian Military institutions still trying to figure out the exact causes and sequence of events that led to India’s last conflict with its western neighbor. To reach the rugged terrain where all the action took place one has to negotiate the mountain ranges of Shivalik, Pir Panjal, Himalayas, Zanskar, Ladakh and Karkoram. It is difficult to envisage now, that a swathe 150 km across this harsh and hostile region resounded with artillery and cannon fire with aircraft and helicopters dropping bombs, firing rocket and guiding PGMs on enemy targets. An exemplary demonstration of initiative and courage by the young officers and soldiers of the Indian Army, assisted by the Indian Air Force uprooted and expelled Pakistani intruders from Indian territory. This war that began during May 1999, ended on July 26, 1999 when India called off all offensive operations.

The enfeebled state of our internal security, and something that directly endangers national security, can be gauged from the fact that a wanted criminal ensconced in Pakistan, continues to run and direct the largest underground network in India.

In the wake of this action at Kargil, the Government of India constituted a high level Kargil Review Committee (KRC) to ascertain the facts leading to the occupation of critically advantageous heights in the sector by Pakistani forces and other related matters. The KRC Report was tabled in the Parliament on 23 February 2000. Some parts of the Report were very candid. To quote:

The KRC findings were highly critical regarding intelligence gathering and dissemination and border management. The need for better communications, improved ‘jointness’ among the three wings of the armed forces, and restructuring of the higher defence organizations were also stressed upon. Based on its findings the KRC made recommendations, some of which were:

The very process that throws up many a politician today is riddled with corruption…it is no secret that many with criminal records enter the Parliament and State Assemblies. These are the people we expect will clean up or change the very system.

“The findings bring out many grave deficiencies in India’s security management system. The framework Lord Ismay formulated and Lord Mountbatten recommended was accepted by a national leadership unfamiliar with the intricacies of national security management. There has been very little change over the past 52 years despite the 1962 debacle, the 1965 stalemate and the 1971 victory, the growing nuclear threat, end of the Cold War, continuance of proxy war in Kashmir for over a decade and the Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA).

The political, bureaucratic, military and intelligence establishments appear to have developed a vested interest in the status quo. National security management recedes into the background in time of peace and is considered too delicate to be tampered with in time of war and proxy war. The Committee strongly feels that the Kargil experience, the continuing proxy war and the prevailing nuclearized security environment justify a thorough review of the national security system in its entirety.

Such a review cannot be undertaken by an over-burdened bureaucracy. An independent body of credible experts, whether a national commission or one or more task forces or otherwise as expedient, is required to conduct such studies which must be undertaken expeditiously. The specific issues that required to be looked into are set out below.”

Following the KRC Report, the Prime Minister set up a ‘Group of Ministers’ (GoM) on 17 April 2000 to “review the national security system in its entirety and in particular to consider the recommendations of the KRC and formulate specific proposals for implementation.” The GoM comprised the Ministers of Home, Defence, External Affairs and Finance. The National Security Advisor was included as a ‘special invitee’. The GoM saw in its mandate ‘a historic opportunity to review all aspects of national security, impinging not only on external threats, but also on internal threats.’ As the scope was very large, the GoM in turn set up four Task Forces to deal with Intelligence Apparatus, Internal Security, Border Management and Management of Defence, each of these headed by eminent and experienced experts. The Task Force Reports came in by 30 September 2000 and the GoM submitted its report in February 2001.

There is no doubt that indigenous weapon systems must get priority over imported ones but these should increase the military’s firepower and not be causes for concern due to poor reliability.

It was rational and logical, for a nation that had undergone the trauma of Kargil, to expect that the government in power, irrespective of their political hue, would get down to business and implement the far-reaching and exhaustive recommendations arrived at after much sweat and deliberations by the GoM. It was rational and logical to expect that in a reasonable period of time, our borders would become less poros, our intelligence agencies would look-out for enemies of the state and not for each other, that our citizens would feel safer in the country as they went about their daily lives and that the armed forces would work jointly in the defence of the nation. But events which followed demonstrated that none of this was likely to happen nor were any serious attempts being made to make our country a safer place to live in.

There are many factors involved in this disease of utter inaction that afflicted the powers that be when it came to implementing tough but vitally essential measures. The very process that throws up many a politician today is riddled with corruption. While the election process has been cleaned up to a large extent, it is no secret that many with criminal records enter the Parliament and State Assemblies. These are the people we expect will clean up or change the very system that has nurtured them. In many cases individual and party interests drive national interests out of reckoning. The situation is exacerbated by the compulsions of coalition politics. The situation has been no different after Kargil.

Visibly, very little or no action was initiated in respect of the interrelated subjects of intelligence agencies, border management or internal security after the GoM report. Whatever was done, only had cosmetic value. If any substantive efforts had been taken to close known loopholes and weaknesses, as also highlighted by the GoM, then an event as catastrophic as the Mumbai terror attacks of 26 November, 2008 could not have taken place. Since the Kargil war and the exhaustive analysis of it, India has had to suffer a large number of terror attacks. These attacks have been across the country and random in nature.

From Chattisinghpura in J&K, through Parliament in New Delhi, American Culture Centre in Kokota, Kalu Chak near Jammu, Akshardham temple in Gujarat, the makeshift Ram temple in Ayodhya, car bombings in South Mumbai, triple blasts in Delhi markets, Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore, the Varanasi explosions, massacre at Doda, the horrific Mumbai train blasts, the Samjhauta Express bombing, Lumbini Park attack in Hyderabad, simultaneous blasts in Lucknow, Varanasi and Faizabad, the Jaipur serial blasts, blasts in Malegaon and Delhi and the unprecedented and audacious strike which crippled Mumbai for more than three days and left an indelible mark in our collective psyche, the terrorists have had a free run across the heart and soul of India. And this after completion of a historic ‘review pertaining to all aspects of national security, impinging not only on external threats but also internal threats’.

The perpetrators of the 26/11 terror attacks still roam free in Pakistan, but USA, supposedly India’s strategic partner, advises India to recommence the stalled dialogue with Pakistan and also thin troops on India’s western border to ‘reassure’ Pakistan.

Jointness among the services remains a chimera. The creation of the Integrated Defence Staff (IDS), but the non-implementation of the Chief of Defence Staff have left the three services where they were earlier on their own. For true jointness, planning and acquisition functions must be integrated. To this day, budget allocation is on time-tested percentage basis resulting in wasteful expenditure and lack of inter-operability. Future wars will be time-critical and real-time communications will be a decisive factor in the outcome of operations. That is why the USA has created a single-backbone C4ISR capability. What this means is that the US army, navy, air force and the marines use the same communications medium during peace and war.

In India, however, each service has opted for different communication systems with the facility of interface. No single back-bone C4ISR has yet been planned.

A single-backbone C4ISR can simultaneously process inputs from disparate sources like satellites, UAVs, AWACS, sigint and humint to present a cohesive and consolidated picture to decision makers without loss of time. In India, however, each service has opted for different communication systems with the facility of interface. No single back-bone C4ISR has yet been planned. The time penalty in such a system could prove fatal, given that we operate in a nuclear environment.

India’s acquisition process is a complex and complicated one. It gives a chance to all and sundry, including those whose bids have been rejected, to cry foul, at which point the entire cycle is gone through again with the resultant time delay in acquiring and operationalizing the concerned product. The Raksha Mantri, on being reappointed to the post after the general elections, said that he would not allow any corrupt practices in the weapon acquisition process and would ensure the guilty are punished. This is an unexceptionable statement, but it is strange that even after so many years, we have been unable to straighten out the system. The damage that delayed acquisitions cause to the national security has to be considered.

The Raksha Mantri said that he would not allow any corrupt practices in the weapon acquisition process and would ensure the guilty are punished…it is strange that even after so many years, we have been unable to straighten out the system.

While India wrestles with various military issues, including the bureaucracy initiated one on pay and perquisites after the 6th Central Pay Commission, our neighbors are spending money and time to improve their respective arsenals. Pakistan, with a fragile democracy which is firmly under army control, with a basket case economy that totters on the brink of collapse and with continuing internal strife which till recently threatened the safety of its nuclear arsenal, has managed to convince the world that it is in the forefront of fight against terror and therefore must be supported by all. And both China, the rising power, and the USA, the only superpower, are providing Pakistan with arms and sophisticated weapon systems. India’s claim that Pakistan is part of the problem is brushed aside and it is told to exercise restraint, even after hundreds of Indian citizens are killed by terrorists trained and nurtured in Pakistan. USA is pumping in billions of dollars into Pakistan to fight terror, but the funds are being misused by Pakistan to acquire weapons that can only be employed against India.

The perpetrators of the 26/11 terror attacks still roam free in Pakistan, but USA, supposedly India’s strategic partner, advises India to recommence the stalled dialogue with Pakistan and also thin troops on India’s western border to ‘reassure’ Pakistan. The latest action by the Pakistan Army is double-edged and the USA knows it but cannot do anything about it. The Pakistan Army is targeting the ‘bad’ Pakistani Taliban, as represented by Baitullah Mehsud who has carried out a series of terror attacks in Pakistan, including the one that killed Benazir Bhutto, but is keeping away from what Pakistan calls the ‘good’ Afghan Taliban, whose cooperation will be required in future to create ‘strategic space’ for Pakistan in an Afghanistan without US and Indian presence. Pakistan has pulled off a diplomatic coup of sorts and Indian diplomacy has failed, but that subject must be addressed elsewhere.

China has been an ‘all-weather’ friend of Pakistan and has time and again lived upto its reputation. During each India–Pakistan war, China has ‘leaned’ on India to try and dilute the forces arrayed against Pakistan. During the Kargil war, satellite images showed weapon shipments from China moving into Pakistan-occupied Kasmir along the Karkoram highway. More than 70 percent of Pakistan’s military hardware, including 1600 MBTs, 400 combat aircraft and 40 naval vessels have been supplied by China. Almost the entire Pakistani military–industrial infrastructure has been established by the Chinese. This includes ‘heavy rebuild factories’ and aircraft manufacturing facilities. Every missile project in Pakistan has been initiated through active Chinese or North Korean assistance. Chinese and North Korean connivance in Pakistan’s nuclear programme has been well documented by international watch agencies. China has trained Pakistani nuclear scientists, provided dual-use technology, built nuclear reactors and provided missile technology to Pakistan.

The China–Pakistan nexus works differently for China. China considers Pakistan as part of its ‘containment through surrogates’ stratagem aimed at India. This stratagem is discernible in China wooing all countries around India. It has helped Sri Lanka, Nepal, Myanmar and Bangladesh economically and militarily. The construction of ports in Gwadar, Myanmar and Sri Lanka allows China to resupply its naval ships in the Indian Ocean. China is conscious that its energy requirements pass through the Indian Ocean and its naval build-up caters to protection of the sea lines of communication that carry this energy. China is actively shoring up its energy security. It has, invested in or partnered with, all oil and natural gas producing nations. Recently China and Iran signed a deal to develop the world’s largest natural gas field, in a deal valued at 4.8 billion USD. The South Paro fields, shared between Iran and Qatar, has an estimated gas reserves of 14 trillion cubic metres – enough to meet Europe’s gas needs for the next 25 years.

The China–Pakistan nexus works differently for China. China considers Pakistan as part of its ‘containment through surrogates’ stratagem aimed at India. This stratagem is discernible in China wooing all countries around India. It has helped Sri Lanka, Nepal, Myanmar and Bangladesh economically and militarily. The construction of ports in Gwadar, Myanmar and Sri Lanka allows China to resupply its naval ships in the Indian Ocean. China is conscious that its energy requirements pass through the Indian Ocean and its naval build-up caters to protection of the sea lines of communication that carry this energy. China is actively shoring up its energy security. It has, invested in or partnered with, all oil and natural gas producing nations. Recently China and Iran signed a deal to develop the world’s largest natural gas field, in a deal valued at 4.8 billion USD. The South Paro fields, shared between Iran and Qatar, has an estimated gas reserves of 14 trillion cubic metres – enough to meet Europe’s gas needs for the next 25 years.

India climbed to great heights during the Kargil war, but thereafter, disappointingly, the journey has been downhill.

Militarily, China has sprinted ahead of India. There was a time when the Indian Navy and IAF were considered superior to their Chinese counterparts, but times have changed – to India’s disadvantage. China has a focussed and time-bound military modernization plan, India’s modernization plan is unwieldy with each service going its own way. The lessons of Kargil on jointness are yet to be learnt. China’s military, the PLA, is pursuing a transformation strategy from a mass army designed for protracted wars of attrition to one capable of fighting short duration high-intensity, high-tech wars in an environment of ‘informatization’ (net-centric warfare). The pace of this transformation has accelerated in recent years with the acquisition of advanced foreign weapon systems (mainly Russian), high levels of investment in its indigenous defence, science and technology sectors and an overhaul of its somewhat archaic military doctrines. China’s ‘strategic reach’ has improved considerably as it focuses on Taiwan and the South-China Sea as potential conflict areas. If these two problems are resolved out, then the only other major territorial issue that China has is with India. China is also developing disruptive technologies for anti-access and area-denial, as well as for nuclear, space and cyber warfare. These will, in future, enable China to project power to ensure access to resources or to enforce claims to disputed territories.

India’s new goverment, with a strengthened mandate, will have to weigh its strategic options. The developing geo-political situation in South Asia holds many pitfalls for India and it will have to play its cards carefully. Some tentative steps like bolstering our troop strength in Arunachal Pradesh and improving the IAF’s strike capability in the eastern sector have attracted sharp remarks from Chinese media, obviously with official backing. India has to fortify its position in the so-called disputed areas to counter any Chinese moves. India has some advantages in the region, especially when it comes to air operations and this should be exploited to the fullest. China will probe our defences and resolve in the near future and the Indian military has to be prepared.

The Kargil war was a warning which we have ignored. The national introspection that followed, gave us the opportunity to overhaul our entire security apparatus, plug the many loopholes, improve internal security, tighten up border and coastal management and modernize our military. But political indifference, diplomatic inefficacy, bureaucratic apathy and military disinterest have brought the country to a situation where its options are being continuously reduced by other players in the international game of geo-politics. The newly elected government has to create strategic opportunities, through positive actions, for the country and steer the ship of the state through the choppy waters to a safer destination. India climbed to great heights during the Kargil war, but thereafter, disappointingly, the journey has been downhill.

Dawood Ibrahim and Shara Pawar are the culprits

Its a four year old article but still looks as of today`s except the referred new Govt has become now four year old. Sometimes I wonder its our general character which reflects in our policies and overall outlook of the Nation. Sir, I must say this is the period 14 years back when our brave officers and jawans had won unbelievable difficult war in Kargil. Some one rightly told in Kargil, a stone thrown from that height was as lethal as a bullet, while our Army faced volley of bullets fired from machine guns and some pica guns of Paki intruders as well other high calibre weapons. I still remember the picture of Shahid Capt. Vikram Batra holding one Pica gun! Yes the new generation doesn`t know about Capt. Batra or Manoj Pandey or those about 450 Shahid Jawans and officers. Its unfortunate that in country of ours there is no value of human life whether that is being lost in accidents, natural or man made calamities, innocent citizens being killed in terror attacks or death of a soldier defending his motherland. Death of air warriors in MIG Crashes, recent petition of right to live by some IAF officer in higher courts have expressed the anguish of the IAF.I am sorry to say but this country will not respect the martyrdom of a soldier till it learn to respect the value of life of its each citizen. It is depressing feeling.