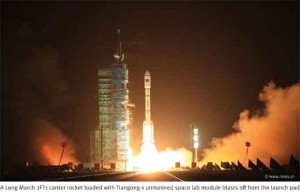

On September 29, 2011, China launched the Tiangong-1 unmanned module from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre in North-West China. The unmanned module was launched by a Long March 2FT1 carrier rocket into a low orbit of about 350kms above the Earth. In Chinese, the word ‘Tiangong’ means a “Heavenly Palace” implying a dream house in the sky, an abode for deities. The Tiangong module, about the size of a railway freight car and weighing nearly eight tonnes, is expected to remain in orbit for the next two years.

The pioneers of the “Space Age” such as American Robert Goddard, German Wernher von Braun the designer of the V2 rocket during World War II and the Apollo project for the US after the War, Russian Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky and China’s Tsien Hsue-shen saw space exploration as a conquest of the moon and journey to distant planets. Their vision was one of adventure and exploration but after six decades of space flight, the race seems to be flagging, now being limited largely to the domination of near space up to a height of 36,000kms above the Earth, where satellites remain in geo-stationary orbit.

The space race was an outgrowth of the development of ballistic missiles and today, the fundamental objection to deep space exploration is its tremendous waste of effort and expense whereas the near-Earth space will remain invaluable as satellites can be employed for a variety of uses ranging from logistics to farming, military surveillance, telecommunications, weather monitoring, TV broadcast and a host of other applications. While the US and Russia will retain their position of pre-eminence in near space till the International Space Station (ISS) remains operational, China hopes to have its space lab in place by 2020, the time when the ISS is to reach the end of its life. China’s Tiangong and Shenzhou space programmes are relentlessly being driven by this objective.

The space race was an outgrowth of the development of ballistic missiles and today, the fundamental objection to deep space exploration is its tremendous waste of effort and expense whereas the near-Earth space will remain invaluable as satellites can be employed for a variety of uses ranging from logistics to farming, military surveillance, telecommunications, weather monitoring, TV broadcast and a host of other applications. While the US and Russia will retain their position of pre-eminence in near space till the International Space Station (ISS) remains operational, China hopes to have its space lab in place by 2020, the time when the ISS is to reach the end of its life. China’s Tiangong and Shenzhou space programmes are relentlessly being driven by this objective.

Palace in Heaven

On September 29, 2011, China launched the Tiangong-1 unmanned module from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre in North-West China. The unmanned module was launched by a Long March 2FT1 carrier rocket into a low orbit of about 350kms above the Earth. In Chinese, the word ‘Tiangong’ means a “Heavenly Palace” implying a dream house in the sky, an abode for deities. With a length of 10.4 metres, the Tiangong module has a maximum diameter of 3.35 metres and is hardly a palace in comparison with the International Space Station. The Tiangong module, about the size of a railway freight car and weighing nearly eight tonnes, is expected to remain in orbit for the next two years. It will be used to validate the operational concepts of docking and undocking and will house Chinese astronauts for long spells in space.

Significantly, the launch date was just prior to China’s National Day on October 01. Since the US Shuttle programme has wound down completely, China’s space lab programme is of special significance. Upon complete assembly, the Chinese space lab will weigh only 66 tonnes when compared to the 431-tonne ISS and the 140-tonne Russian Mir.

Rendezvous in Space

On November 01, 2011, the Shenzou-8 spacecraft was launched from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre and after a two-day orbital chase, latched onto the Tiangong-1 space lab module. Chang Wanquan, the Chief Commander of China’s Manned Space Engineering project, announced the successful achievement of the docking sequence designed to test technologies that China will use to assemble a space station in the coming decade. China has developed the technologies indigenously as dependence on foreign sources would be fraught with constraints.

After lift-off from Inner Mongolia, the initial manoeuvreing was controlled from the ground but after the Shenzou-8 spacecraft came within 50kms of the Tiangong-1 space module, its onboard sensors took over and the spacecraft guided itself towards Tiangong-1 and docked with it successfully 350kms above the Earth. The inter-locked Tiangong-1 module and Shenzou-8 spacecraft orbited the Earth for 12 days and then to prove beyond doubt that China had mastered the technology for docking in space the Shenzou-8 undocked, fell back to a distance of 140 metres and repeated the docking exercise. After disengaging for its journey back to Earth, Shenzou-8 landed safely on November 17 at a site in Inner Mongolia. The Shenzou-8 mission is to be followed by Shenzou-9 which will carry one astronaut and later by Shenzou-10, which will carry two or three astronauts, one of whom may be a woman.

China’s Space Ambitions

The recent pirouette in space by Tiangong-1 and Shenzou-8 is merely a small facet of China’s manned space programme. China had begun the initial planning of its space programme in July 1985 against the backdrop of very active space programmes of the leading space-faring nations. The US was working on the Strategic Defense Initiative and Space Station Freedom. The USSR had the Buran Space Shuttle system, the Mir Space station and its own Star Wars programme. Europe was developing the Hermes manned space plane and Japan, the Hope winged spacecraft. India was also entering the fray.

In 1986, members of the standing committee of the Chinese Academy of Sciences proposed initiatives to accelerate development in the fields of biology, astronautics, information technology, military technology, automation, energy and material sciences. The plans called for a space station and a space transportation system as also to develop on parallel track, a vertical take-off and re-useable shuttle spacecraft. However, in 1989, President Deng Xiaoping had rejected the plans. Three years later, fresh plans were drawn up as Project 921, which proposed a manned flight in the Shenzou spacecraft in 2003 followed by the establishment of a permanent space station. In 1992, a three-phase plan was presented and approved.

In 1986, members of the standing committee of the Chinese Academy of Sciences proposed initiatives to accelerate development in the fields of biology, astronautics, information technology, military technology, automation, energy and material sciences. The plans called for a space station and a space transportation system as also to develop on parallel track, a vertical take-off and re-useable shuttle spacecraft. However, in 1989, President Deng Xiaoping had rejected the plans. Three years later, fresh plans were drawn up as Project 921, which proposed a manned flight in the Shenzou spacecraft in 2003 followed by the establishment of a permanent space station. In 1992, a three-phase plan was presented and approved.

- Phase 1: Launch of unmanned versions of the Shenzou spacecraft followed by a manned flight in 2002.

- Phase 2: This phase would continue for five years and involve a series of space flights to prove the technology, conduct rendezvous and docking in orbit and operate an eight-tonne space lab using basic space technology

- Phase 3: This would involve orbiting a 20-tonne space station by 2015 with crew shuttling between the space lab and the Earth.

The first models of the proposed space station were displayed at Expo 2000 in Hanover, Germany. In the years 2001 and 2002, there were media reports in China of the space lab and thereafter, there was no report of this programme till February 2004, when it was announced that the first space module would be launched only after Shenzou 6, 7 and 8 missions had proven basic rendezvous and docking capabilities.

The Shenzou programme was central to the development of the space lab as it had to establish the operational capabilities of various technologies developed in China. A building-block approach was designed where Shenzou-1 was launched on November 20, 1999, to examine the performance and reliability of launch systems and the technologies related to capsule connection and separation, heat management and telemetry.

| Editor’s Pick |

On January 16, 2001, Shenzou-2, the first formal unmanned spacecraft was launched and China conducted experiments related to space life sciences, space material, micro-gravity and space astronomy. Shenzou-3, launched on April 01, 2002, was the precursor to manned flight, the spacecraft carried a dummy astronaut with human physical monitoring systems and the craft also had escape and emergency rescue functions. Shenzou-4, launched on December 30, 2002, addressed some of the issues with earlier flights. On October 15, 2003, Shenzou-5 lifted off with astronaut Yang Liwei onboard and was China’s first manned space flight remaining in orbit for less than a day.

Thus China became the third nation after the US and Russia to launch a human into space. The next logical step was to increase the number of astronauts in the spacecraft and keep them aloft for longer durations. Shenzou-6 was launched on October 12, 2005, with two astronauts, Fei Junlong and Nie Haisheng, who stayed in space for five days. Astronauts are required to move out of the spacecraft in the initial construction of the space lab and later, for repairs if the need arises. Extra-vehicular mobility is mission-critical for establishing a permanent space lab.

The Technology Race

The Shenzou-7 mission with three astronauts, Zhai Zhigang, Liu Boming and Jing Haipeng was launched on September 25, 2005, and Zhai went out of the cabin for a space walk. With that, China joined the exclusive club of US and Russia as the few nations to have developed this technology. The initial Shenzou missions validated the procedures, processes and technology for basic manned flight but the crucial rendezvous, docking and disengagement technologies essential for setting up a manned space station were yet to be tested. The Tiangong-1 module was used to validate the operational concepts of docking and undocking and the viability of housing Chinese astronauts for long spells in space.

Shenzou-8 closed the loop on this vital facet by docking successfully with Tiangong-1 and the follow-on launches of Shenzou-9 and Shenzou-10 missions will enlarge the scope by shuttling astronauts to the “Heavenly Palace” for extended stay and extra-vehicular activities of greater complexity. By 2015 China plans to launch Tiangong-2 and Tiangong-3 space modules which are to support astronauts for 20 and 40 days respectively.

“The Tiangong-1 mission was a complete success,” said Chang Wanguan, and according to the Chief Designer of the programme, Zhou Jianpeng, “The mission was flawless.” Zhou admitted that despite tremendous progress in this field, China’s aerospace technology was still lagging behind that of the US and Russia. He added that China did not have the rocket thrust motors necessary to lift a 20-tonne payload needed to build the permanent space station but this was under development. Phase 3 of Project 921 involves placing a space station into orbit but its launch hinges on the development of the Long March-5, the next generation heavy-lift launch system currently under development by the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology. The Long March-5 will have the ability to lift a payload of up to 25 tonnes into a low earth orbit or a 14-tonne payload to a geo-stationary transfer orbit. This would put the Long March-5 in a category second only to Boeing’s Delta IV heavy-lift rocket. China hopes that the Long March-5 would be ready for launch by 2014 from the Wenchang Satellite Launch Centre on Hainan Island. Li Hong, Head of the Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology assesses that China would be able to produce 20 to 30 carrier rockets each year configured for different payloads.

China had embarked on indigenous development of its space station after being rebuffed in its attempts to join the ISS programme largely on the objections by the US. China claims that she has spent only 33 billion Yuan (US$ 5.4 billion) on the manned flight programme. In contrast, the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration has an annual budget of around $18 billion. However, data on Chinese Government expenditure is far from transparent and extremely difficult to authenticate. Wang Zhaoyao, Deputy Director of China Manned Space Engineering Office (CMSEO) stated that China welcomed involvement by other countries on the basis of “mutual respect, mutual benefit, transparency and openness”. Teams from CMSEO have visited space facilities in Israel, Europe, Russia and Canada. These visits are significant as Canada developed the space arm fitted on the Shuttle, Russia provided suits for the Chinese astronauts for the extra-vehicular activities and Germany has been closely associated in the biological experiments.

China had embarked on indigenous development of its space station after being rebuffed in its attempts to join the ISS programme largely on the objections by the US. China claims that she has spent only 33 billion Yuan (US$ 5.4 billion) on the manned flight programme. In contrast, the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration has an annual budget of around $18 billion. However, data on Chinese Government expenditure is far from transparent and extremely difficult to authenticate. Wang Zhaoyao, Deputy Director of China Manned Space Engineering Office (CMSEO) stated that China welcomed involvement by other countries on the basis of “mutual respect, mutual benefit, transparency and openness”. Teams from CMSEO have visited space facilities in Israel, Europe, Russia and Canada. These visits are significant as Canada developed the space arm fitted on the Shuttle, Russia provided suits for the Chinese astronauts for the extra-vehicular activities and Germany has been closely associated in the biological experiments.

Although China is developing its space station on its own, it seeks collaboration from other nations in the operation of the permanent space station and further exploration of space. It appears that the Chinese spacecraft design with minor modifications would even be compatible with the docking system of the ISS. China has even acquired a space tracking station in Dongara, a remote region of Western Australia about 350kms from Perth. China views this facility at Dongara as a major step in her quest for global stature in the space arena. The Australian facility was built by Swedish Space Corporation and is on lease to China after approval by Australian authorities. This is the fifth station outside China, the others being in Chile, Kenya, Namibia and Pakistan. Australia now finds itself in a situation where it will have a US Marine base and a Chinese space facility on its territory!

Strategic High Ground

Zhou Jianpeng, Chief Designer of China’s manned space programme proclaims that China’s space programme is peaceful and will help to explore and use space for the good of mankind. However, Western nations and India are wary of China’s space programme ever since she demonstrated the ability to destroy a satellite in space with a kinetic kill. This stunning demonstration of China’s prowess of bringing down a satellite, traveling as fast as an Inter Continental Ballistic Missile re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere, showed China’s ability to weaponise space. The US weapon systems that China wants to blunt are not space-based; they are the US naval and air forces which are dependent on space-borne systems for Command, Control, Communications and Intelligence. China appreciates that it can blunt the operational capability of US forces by targeting American space assets.

Ever since Operation Desert Storm in 1991, Chinese strategists have been grappling with ways to overcome the conventional forces of the US and her allies. Lessons from the Persian Gulf War, Kosovo and Afghanistan have demonstrated America’s dependence on space-based assets. “The ability to neutralise American space systems would permit a weaker Chinese military to deter, delay, degrade or defeat superior American forces and level the playing field in a shooting war,” says Ashley Tellis of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington. He adds that while China may never go to war with the US, she appreciates that America’s dependence on space-based assets constitutes the strategic weakness of US forces. For countries that can never win a war against the US with planes and tanks, attacking the US space system may be an irresistible, viable and tempting option.

China is developing a multi-dimensional programme to improve her capability to limit and prevent the use of space-based assets by adversaries during times of crisis and conflict. Dr Wu Chunsi of the Centre for America Studies at Fudan University offers another perspective that those who dwell on the military component of China’s space programme underestimate its greater strategic significance. The initial development of the space programme was entrusted to the military whose involvement has now reduced.

| Editor’s Pick |

While space applications have dual use, China is focusing on the commercial objectives. She claims that the US is the only nation that has the capacity to exploit space-based assets for military use and wants to maintain the status quo. She adds, “The Chinese government has recognised that its security interests lie in preventing the weaponisation of space and taking precautions against the negative effects of military operations on commercial and civilian activities in space.”

Having initiated its three-stage manned space flight programme in 1992, China is leaping forward on schedule. Chief Designer Zhou says that by 2020, China will offer its space lab as a platform for international co-operation. The assembly of China’s space lab will herald her presence in the ‘big league’ and China will take the strategic high ground in space when its “Heavenly Palace” space lab plays host to the astronauts of the world.

Notes

- The Economist, USA.

- The Straits Times, Singapore.

- Dr Ashley Tellis, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Dr Wu Chunsi, Centre for American Studies, Fudan Univesity.

- Chinese Manned Space Engineering Office.