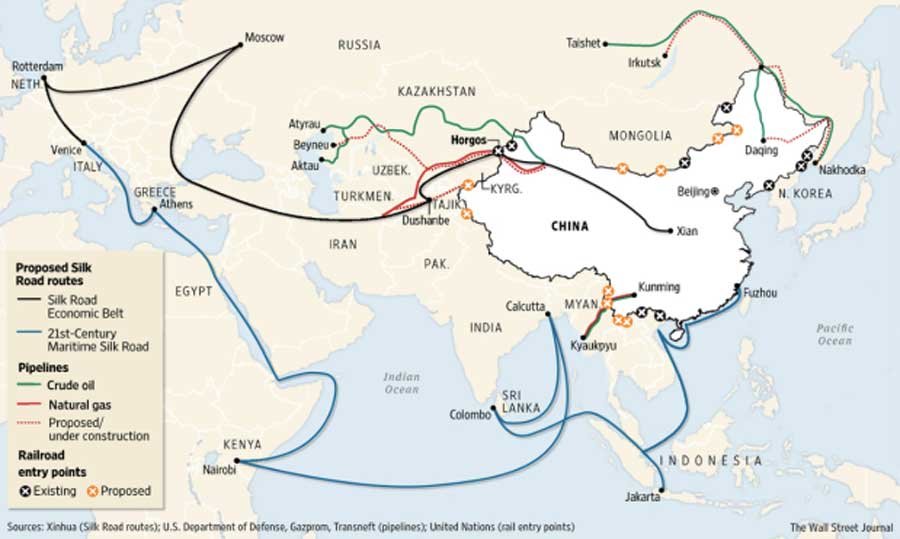

China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI) of which the SREB is one part has generated apprehension in many of its host countries. There is often an extreme lack of transparency in many deals under the BRI framework and strong concerns that China is exporting obsolete and polluting industries outside its borders. The impression has gained ground that BRI projects are more a case of subtle Chinese economic and political coercion than genuine collaboration with host countries. China appears more invested in supply chains onwards to larger markets in Europe and not so much in production or value chains within Central Asia itself. China is, at this point, engaged more in trade than in actual investments in the region.

The primary objective for China is, of course, the maintenance of stability in Xinjiang…

China is deepening its ties with Central Asia through the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) initiative. Cooperation with the Central Asian Republics (CARs) that was already quite intense in the field of trade, especially in the energy sector, is broadening into infrastructure development with an eye on strengthening the region’s role as a transit hub for Chinese products moving to the more prosperous and bigger markets of Europe.

The primary objective for China is, of course, the maintenance of stability in Xinjiang, which is a key Chinese province and actor in the SREB. Despite all the troubles in Xinjiang, however, the province is today considerably better off economically than most of its eight neighbouring countries. Beginning in the 1990s, China-CAR trade through Xinjiang has expanded and today, several companies from the province have a strong presence in Central Asia. For example, the Xinjiang-headquartered Chinese enterprise TBEA that has promoted connectivity in Central Asia by building power transmission lines in Kyrgyhzstan and Tajikistan. It is also noteworthy that there is a flight from Urumqi to every CAR capital and to many other cities as well. Indeed, many of these countries are connected to each other by air not directly, but via the Xinjiang capital.

However, there are several other challenges that the Chinese both face and can potentially run into while implementing the SREB in Central Asia. These include the murmurs of protest and disaffection with regard to Chinese economic activities in the region, the inevitable passing from the scene of the CAR’s long-ruling dictators, the ever-present threat of Islamic radicalism and, of course, India’s own soft power in the region and desire to challenge China’s political dominance. In addition to pursuing economic dominance and stability in its political and security relations, China has, in response, begun efforts also to control and direct historical and political narratives in the region.

The fact is that political opposition in many CARs is being weakened or stifled…

Political Challenges

China’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ (BRI) of which the SREB is one part, has generated apprehension in many of its host countries. There is often an extreme lack of transparency in many deals under the BRI framework and strong concerns that China is exporting obsolete and polluting industries outside its borders. The impression has gained ground that BRI projects are more a case of subtle Chinese economic and political coercion than genuine collaboration with host countries. China appears more invested in supply chains onwards to larger markets in Europe and not so much in production or value chains within Central Asia itself. China is, at this point, engaged more in trade than in actual investments in the region.

The Chinese counter to such concerns is to state in a rather oblique manner, that the fields in which China is cooperating with the CARs, are getting wider and broader. Energy cooperation, for instance, is just one aspect; large-scale infrastructure development projects are increasing under the SREB accordingly and this construction is matched with the development needs of the CARs in terms of industrialisation and modernisation. As a result, Chinese scholars contend that all five CARs actually hold positive attitude towards the SREB.

On the political front, the strongman-centered regimes of the CARs, while at once allowing Chinese SOEs easier access with lesser accountability than in the developed West, also create risks of generating hostility to Chinese activities from disaffected populations as well as potentially unfriendly successors to these strongmen. The fact is that political opposition in many CARs is being weakened or stifled and actually possibly weakens also secular politics in the region and consequently creates a still stronger inclination towards Islamist radicalism.

The security side of the Chinese response to the potential challenges from Islamic radicalism-driven security challenges is well known…

In formal interactions, however, Chinese think-tank scholars appear rather sanguine about these issues. They point out that the CARs had their own culture and political traditions. If after independence, they chose Westernised democratic institutions and if Presidents in these countries got elected by up to or over 90 per cent of the vote, it only meant that the Central Asian people saw their leaders and systems as working for them. At the same time, referring to the experiences of Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan as having followed the ‘colour revolutions’, the Chinese seem to suggest that not all change is a good thing. In noting that the CARs had a history of just over 25 years of independence, they seem to imply that the Central Asia nations had to be given more time to find their feet. From the Chinese point of view, more important than the issue of leadership transition itself was the ability of the successors to the long-time rulers of the CARs to have the ability to maintain stability.

India in the SCO

The security side of the Chinese response to the potential challenges from Islamic radicalism-driven security challenges is well known. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) is a very useful multi-lateral aegis that China helped found under which takes place both regular meetings between security officials and anti-terror exercises. In this context, it is useful to examine more closely the meaning of China’s agreeing to India’s membership of the SCO.

New Delhi has, of course, for long aspired to be a member of the SCO and it is seen as something of a coup for India that it was able to gain entry while keeping the Chinese out of formal membership of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), something which the Chinese too, have long aspired for.

This narrative is perhaps only what the Chinese wish the Indians to believe. Consider the reality. India’s lack of direct geographical access to Central Asia has not changed and does not look like it is about to change either, given India’s strenuous objections to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) on the grounds that it passes through Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir. New Delhi has, in effect, turned down the only possibility for the moment at least, of physical road and trade connectivity with Central Asia. Perhaps, the Chinese anticipated this self-defeating behaviour from India while agreeing to the SCO membership. Pakistan, that also became a member of the SCO along with India is, by contrast, poised to exploit the benefits of the linkages between the CPEC and the SREB.

New Delhi has, of course, for long aspired to be a member of the SCO…

Next consider what India can actually bring to the table in so far as working in the SCO framework is concerned. To questions about how specifically India and China could cooperate in the Central Asian energy sector, a Chinese scholar at a conference in Beijing last year pointed out that capital and technology requirements in Central Asia were quite high and that China, the European Union or the United States could not meet the demand by themselves and so India could well contribute. However, no one can be unaware that neither capital nor technology in this sector is among India’s strengths.

Again, the Chinese highlighting the fact that their interests in the CARs were more security-oriented than economic and that China was willing to help without expectations of profit, only shows up India’s shortcomings. The wide gap in economic resources between the two countries means that such a generous approach is not possible for India beyond a point.

The attempts at setting or directing the narrative for India in the SCO do not end here. Chinese scholars have suggested that the SCO provides a platform for India and Pakistan to help resolve their bilateral problems, as it did for Russia and the CARs to resolve their boundary disputes with the Chinese. The ‘spirit of SCO’ they claim, has helped in resolving difficult problems through ‘equal dialogue and mutual discussion’. In other words, the SCO provided a platform also to help resolve Indo-Pak issues and it was not just the heads-of-government meetings but also commercial and other platforms that could be used for this end.

India’s lack of direct geographical access to Central Asia has not changed and does not look like it is about to change either…

The onus however, always seems to be on India to play a more active and constructive role. Perhaps, this is only fair given its larger size, resources and strengths vis-à-vis Pakistan. But the problem is also that the Chinese narrative on what constitutes terrorism is at variance with India’s as is evident from its repeated blocking of Indian efforts to declare Pakistan-based terrorists on the UN sanctions list. What is more, it is unlikely that New Delhi will have any purchase for its views on terrorism at the SCO especially with Pakistan also as a member.

Thus, if the Chinese statements are to be seen in their totality, then it is evident that despite the rhetoric of an Indian role in Central Asia, the Chinese do not really see India as having the potential to do anything concrete. Their rhetoric, however, is useful diplomatic cover.

‘Fixing’ History

Given the combination of its own problems in Xinjiang and the issues of political stability and potential opposition to the SREB in some form or the other, another major effort by China at controlling the narrative is also underway. The Chinese are increasingly investing in efforts to control discourse, the mind-space as it were, on issues related to culture and history in the region.

Chinese scholars have suggested that the SCO provides a platform for India and Pakistan to help resolve their bilateral problems…

This sort of control is particularly important to China given that its borders with Central Asia are dominated by minority ethnic groups with trans-border ethnic ties. China’s original economy-oriented plans took this into consideration under the belief that a stronger economy in Xinjiang would dampen separatist tendencies or dissatisfaction among ethnic minorities on the Chinese side of the border. To an extent, this has worked. However, increased economic prosperity has not entirely subdued the Uyghur ethnic separatist movement. What is more, it also appears to be picking up a radical Islamist tinge at least in sections of the movement. Other ethnic groups have their own set of dissatisfactions even if these have not erupted into full-blown violence as in the Uyghur case.

As a result, China seems to have come around to the view that political stability within Chinese frontiers requires an understanding and possibly also the reordering and reinterpretation, of core aspects of ethnic history and cultural production across the region. Of course, this has always been a part of Communist China’s efforts in all minority areas. What is different in current efforts is that these efforts appear no longer driven by a communist worldview, but by an older sense of Han dominance on the one side and the historical sway of the imperial Chinese state over its neighbours on the other.

Now, in addition, scholars in Xinjiang are being encouraged through heavy state funding to focus on studying their own culture, traditions and literature as well as of their Central Asian neighbours. In particular, there is a focus on translating and studying the ancient epics common to the various ethnic groups of the region such as the 18th century (and possibly older) Kyrgyz epic Manas, for example, that exists in several versions and is popular also among Uzbeks and Kazakhs among others. However, the focus of scholars in Kashgar is on the epic of Oghuz Khan – whose ambition was to conquer the entire world including India – dated to the 13th or 14th century and possibly originating from Eastern Turkestan which thus makes it older than the Manas and only slightly later in origin than the Gesar, the epic that dominates Tibet and Ladakh.

India must also study the re-examination of Central Asian epics being carried out in Xinjiang and Tibet…

What does the focus on these ancient epics say about the Chinese state? Given that Oghuz Khan is considered the mythological founder of the Turkish people, a Chinese state-dominated narrative and interpretation promoted through the Uyghurs in the Turkic world has several implications. One, as a people belonging to a territory controlled by China, the Chinese state has legitimate access to historical memories and discourses in its extended neighbourhood. Indeed, the legend of Oghuz Khan has already been subjected to modification in the past by Mongol and Islamic rulers in Central Asia. The evil Chinese stepmother and half-brother of legend can be whitewashed. Already in Kashgar, the stories around important local figures of history who acted in opposition to Chinese imperial rule have been rewritten in public spaces to promote Chinese state objectives of ethnic unity.

Two, by trying to promote the Oghuz Khan as something on par with if not seeking precedence over the Manas as appears to be the case, there is also a hierarchical ordering of narratives in the wider region. This is evident from the fact that Uyghur scholars are dating the Oghuz Khan to the 10th century and stating that the Manas borrows from the Uyghur epic in terms of content and structure.

These could well be true but such assertions appear to be made in a vacuum at the moment away from challenge by other non-PRC scholars. For instance, the Uyghur scholars at Kashgar appeared to be working independently without having accessed Uzbek translations of the Oghuz Khan from the Soviet era. It seems obvious that, as in other aspects of Chinese state activity with respect to historical claims and assertions, the wait is only to find material that makes such claims stronger still and/or to complete the other diplomatic or economic efforts to ensure that these claims are not challenged and accepted more easily.

Indian soft power in South-east Asia is of little practical consequence today…

This is buttressed by additional claims of Kashgar having greater influence on Central Asia than vice versa, that the Uyghur oasis was the centre of Central Asian civilisation, once called ‘little Samarkand’ or ‘little Baghdad’. Uyghur madrassas are said to have exercised great influence on neighbouring people with neighbours coming to Kashgar to study. Today, this tradition continues with support from the Chinese state with students from the Central Asian countries studying in large numbers in Kashgar on scholarship. Of course, the references to the ‘one belt, one road’ are never far away with Kashgar seen as a base of both the old Silk Route and the current SREB.

Three, that the objective is essentially to shape future politics is obvious when a Kashgar scholar claims that epic literature is not just history but remains deeply influential among even the Uyghur young today. From here, it is but a simple extrapolation to wider Central Asia.

Ladakh as India’s Trump Card

The connection made in Kasghar between the ancient and the present, between the study of ancient epics and the BRI suggest that such linkages are hardly casual in nature. Given the long-term nature of these Chinese efforts, this is probably the more serious challenge to India. Just as Indian soft power in Southeast Asia is of little practical consequence, what little soft power it enjoys today in the Central Asian region because of present-day Bollywood or past historical connections, are likely to be wiped clean under pressure of both Chinese economic ingress and politicisation of folklore in the region.

New Delhi has constantly brought up the issue of lack of geographical contiguity in the case of its outreach to Central Asia…

New Delhi has constantly brought up the issue of lack of geographical contiguity in the case of its outreach to Central Asia. However, it has ignored the possibilities offered by Ladakh. Even if Ladakh’s geographical connection to the Central Asian Republics is through the narrow India-China international boundary at the Karakoram Pass and through Xinjiang, the Chinese diversion into the mythical and epic literatures of the region should encourage Indian policymakers also to promote examination and rediscovery of local lore and literature in its border areas and Ladakh’s role as a centre of culture and trade on the ancient Silk Road similar to the role that Kashgar and various Xinjiang cities see for themselves.

By converting Lehand Kargil into hubs of culture, literature and historical studies, not only can Ladakh’s own cultural traditions receive a fillip, but a contrast with the Chinese created with India’s role as a place where the Central Asia’s common cultures can be studied, discussed and promoted without prejudice and falsification of history as is the case in China. Dominating the Central Asian mind-space and discourses might be a new way to allow Ladakh to overcome the tyranny of geography. It might also allow India to fashion a new pivot to Central Asia.

As part of this pivot, India must also study the re-examination of Central Asian epics being carried out in Xinjiang and Tibet and find ways of keeping these efforts honest and based on facts as far as possible. This would also be an endeavor to help bolster and maintain the plurality of historical traditions and narratives in Central Asia. One way could be to promote conferences and/or festivals centered around these epics in Ladakh that invites scholars and experts from all across the world and to do so on the same scale as other Indian government efforts such as the various region-specific forums and bilateral and multilateral think-tank forums that the Ministry of External Affairs currently sponsors.

Finely articulated – thank you for an interesting read and material for thought. Whether political thought will rise up to the task at hand remains to be seen.