As Asian Nations work towards integrating familiar areas of mutual interests, defence cooperation by and large, serves as a significant tool that complements diplomatic enterprise. Collaboration in the realm of defence is widely considered a visible manifestation of a strategic relationship thereby fostering bilateral ties including political and economic relations and specific national security interests, crucially counting military capabilities.

Of all the controversies that have surrounded Iran of late, specifically the debate surrounding Tehrans nuclear programme, India has made lucid efforts to project the Iranian case as symbolic of the sovereignty of New Delhis foreign policy orientations. The complexities of Indo-Iranian ties could be attributed to the “˜American angle that looms large over this equation as New Delhi walks a tightrope whilst its ties with the United States (US) burgeon. In addition, fostering a close relationship with Israel also proves to be a litmus test for New Delhi vis-à -vis Tehran.

Iran holds particular importance for India as it provides unique access to Afghanistan and Central Asia, two theaters in which India seeks to project greater influence.1 As New Delhi promulgates a “look-east” policy to develop and sustain a multifaceted presence in the greater Middle East, Iran unquestionably is an instrumental player in this set up.2

Defence and Military-to-Military Collaboration

India and Irans strategic partnership has significantly put in place military and energy deals estimated over $25 billion. The wide-ranging cooperation involving all three military services is quite a turnaround in the existing strategic situation in Southern Asia especially since the last two decades. In fact, the 2005-06 Annual Report of the Ministry of External Affairs in New Delhi claimed that Indo-Iranian cooperation had “acquired a strategic dimension flourishing in the fields of energy, trade and commerce, information technology and transit.”3

The complexities of Indo-Iranian ties could be attributed to the ‘American angle’ that looms large over this equation as New Delhi walks a tightrope.

The establishment of the Indo-Iran Joint Commission in 1983 was instrumental in so far as forging New Delhis defence and military ties with Tehran. As the protracted Iran-Iraq war drew to a close in 1988, Tehran felt the need to rebuild its conventional arsenal and for this purpose initiated the process of purchasing tanks, combat aircraft and ships from Russia and China. Further, Iran reportedly solicited Indian assistance in 1993 to help develop new batteries for three Kilo-class submarines it had purchased from Russia. The submarine batteries provided by the Russians were ill-suited to the warm waters of the Persian Gulf, and India possessed substantial experience operating Kilo-class submarines in warm water.4 In addition, Iran remains inclined to acquire Indian assistance for other upgrades to Russian-supplied military hardware, which includes MiG-29 fighters, warships, subs, and tanks.

Defence ties between India and Iran further evolved post signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on defence cooperation in 2001. It was in the same year that Indias Defence Secretary, Yogendra Narain, met his Iranian counterpart, Ali Shamkani, and supposedly discussed arms sales to Iran including Indian Konkurs anti-tank guided weapons and spare parts.5 India and Iran are hopeful that New Delhi will become a source of conventional military equipment and spare parts for Iran, provide expertise in electronics and telecommunications and hold joint training exercises with Iranian armed forces. Tehran also seeks New Delhi to provide combat training for missile boat crews as well as simulators for ships and submarines and purportedly anticipates that India provide midlife service and upgrades for fighters, warship, and subs in Indian dockyards.6

Bilateral defence and security ties received a boost as Iranian President Hojjatoleslam Seyyed Mohammad Khatami paid a state visit to India in January 2003 where he was the guest of honour at Indias Republic Day. In a landmark accord, the two nations agreed upon future Iranian access to Indian military technology. According to the New Delhi Declaration:

The Republic of India and the Islamic Republic of Iran are resolved to exploit the full potential of the bilateral relationship in the interest of the people of the two countries and of regional peace and stability”¦ with a vision of a strategic partnership for a more stable, secure and prosperous region and for enhanced regional and global cooperation”¦ Explore opportunities for cooperation in defence in agreed areas, including training and exchange of visits.7

Given its timing, the conduct of the exercise signaled to Tehran and Washington alike that Washington will not dictate India’s foreign policy.

The declaration called upon the two states to broaden their strategic collaboration in third countries-a clear reference to Afghanistan. Significantly, the New Delhi Declaration, apart from expressing discomfort with mounting US military presence in Persian Gulf, sought to upgrade defence cooperation between India and Iran specifically in the following areas:

- Sea-lane control and security.

- Indo-Iran joint naval exercises.

- Indian assistance to Tehran in upgrading its Russian made defence systems (yet to fructify).

- Establishment of joint working groups on counter-terrorism and counter-narcotics.

According to reports, India would purportedly be given access to Iranian military bases in the event of a war with Pakistan.8 India reportedly hoped that the 2003 New Delhi Declaration would pave the way for upgrades of Irans Russian-made conventional weapon systems by India. While Indo-Iranian deals along these lines have not yet materialized, Iran has sought Indian advice in operating missile boats, refitting Irans T-72 tanks and armored personnel carriers, and upgrades for MiG-29 fighters.9 Although there was a clear mention of military ties expanding further, the US State Department expressed concern but dismissed any anxiety over the developments stating that New Delhi had reassured Washington that the agreement “doesnt involve military and technical assistance.”10

Two months after President Khatamis visit to India, in March 2003, Tehran and New Delhi conducted their first joint naval maneuvers in the Arabian Sea. Sea-lane control and security, as well as discomfort with the emerging US presence in the Persian Gulf, were partially responsible for this exercise. Another exercise was held in March 2006. Defence cooperation beyond this, however, has been sporadic and low-level.11 The timing of the second naval exercise in March 2006 was crucial as it overlapped with President George Bushs visit to Afghanistan, India and Pakistan. Given its timing, the conduct of the exercise signaled to Tehran and Washington alike that Washington will not dictate Indias foreign policy.12 As a matter of fact the joint naval drill in 2006 prompted US Congressional criticism, but both the Bush Administration and Indian officials insisted the exchange emphasised mutual sport activities rather than military techniques13-in what was an obvious effort to play down the growing spotlight over this development.

According to reports appearing in September 2007, Iran is negotiating with India to purchase advanced radar systems designed for fire control and surveillance of anti-aircraft batteries. Iran is seeking an unspecified number of Upgraded Support Fledermaus radar systems from the Indian state-owned Bharat Electronics Ltd (BEL). The deal could touch a staggering $70 million and mark the first major defence agreement between New Delhi and Tehran. However, New Delhi faces intense pressure from Washington to not to sell the radars to Iran, as it is convinced that the request is part of Irans military effort to protect its nuclear weapons facilities in question. The upgraded Super Fledermaus is a monopulse radar used in 35-mm air defence batteries and designed to detect low-flying objects, such as unmanned air vehicles (UAVs). The digital system contains a built-in simulator as well as a signal jammer. Crucially, BHEL has gone on record and confirmed Irans request for these upgraded radars. Executives at the plant stated that Iran sought the same fire control and surveillance radar that the company upgraded for the Indian Army way back in 2001.

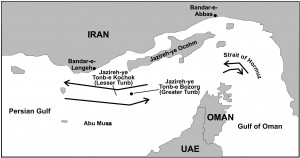

Adding on to the nascent military ties, India has also developed intelligence outposts in Iran, including the Indian consulate in Zahedan and a relatively new consulate in Bandar Abbas, which will permit India to monitor ship movements in the Persian Gulf.14 The two countries have not only undertaken to cooperate in space research but collaborate as well.15 Moreover, India can also offer medium-technology weapons such as medium-range howitzers, and more prominently, jointly train with the Iranian forces.

As India assists Iran to construct railway spurs linking its rail network to that of Central Asia, the process considerably reduces Pakistans strategic leverage over these landlocked states thus providing them alternative corridors to the sea. New Delhi has undertaken vital development of Iranian port facilities along with the construction of road and rail links. Indian engineers have contributed immensely towards the upgradation and development of the Iranian port of Chahbahar. In fact, Indias Ministry of External Affairs has claimed: “New Delhi and Tehran have agreed to “˜join hands in the reconstruction of Afghanistan and to support the development of “˜alternative access routes to that country (bypassing Pakistan) via Irans Chahbahar port.”16 This shall presumably facilitate trade and is part of a larger Indian Ocean to North Sea initiative involving Russia and others, and mainly centered on the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas.

Moreover, India is developing Chahbahar and is laying railway tracks to connect it to Zaranj in Afghanistan, proclaiming that this would be a commercial port. Additionally, India has constructed the 218 kms long Zaranj-Delaram highway that now links Afghanistan to the Iranian port of Chahbahar as part of the Afghan circular road that connects Herat and Kabul via Mazar-e-Sharif in the north and Kandhar in the south- thereby providing easier access to Afghanistan and possibly even further, to Central Asia via Iran.17

Attaining Strategic Congruence through Defence Cooperation

Defence cooperation proves critical in facilitating regional security and further cementing alliances with nations in the extended neighbourhood. Defence cooperation with Iran would go far so as to project Indias role in the regional security structural design. Assessing the opportunities available for military cooperation with Iran, it is evident that Tehran is searching for sustained support in modernisation of its armed forces which have been suffering from lack of access to advanced technology, maintenance and spares support. Developing early stakes in the process would be a major advantage for India. For this purpose, commencing a defence dialogue could be envisaged, which could be progressed based on international and regional developments, providing opportunities for greater cooperation with Iran without necessarily impinging upon Indias relations with other states in the region or with the United States.18 The band of opportunities is not necessarily sequential or time constrained and could be envisaged in the following fields:

India and Iran have a major stake in keeping the Gulf waterways open for trade and energy flows. Towards this end, India and Iran envisaged naval cooperation for sea-lane control and security.

- Assistance in modernisation of defence forces to include supply of arms and equipment as per Indias national policy from time to time

- Defence research and development (R&D) assistance

- Strategic defence dialogue

- Training and exercises

- Courses

- Defence infrastructure development

- ITisation of the armed forces

- Maintenance assistance, supply of spares and ancillaries.19

It would also be evident that there are very limited reverse spin offs that would be accrued to the Indian military. However, defence cooperation would very effectively serve the larger aim of building a strategic relationship with Tehran as and when such an opportunity becomes visible or is envisaged. Being situated on Pakistans western borders, Iran provides significant politico-strategic advantage for India. This provides a strong congruence of Indo-Iranian interests in ensuring a moderate regime in Kabul that is not a client of Pakistan. Afghanistan is critical to Indias security and Iran can provide a major stabilising influence there. Accordingly, engagement of Iran implies an engagement with its armed forces and the need for fostering military-to-military relations. This could translate into sharing of intelligence regarding terrorist groups operating out of Afghanistan and curbing the activities of narcotics smugglers and drug traffickers. India and Iran have a major stake in keeping the Gulf waterways open for trade and energy flows. Towards this end, India and Iran envisaged naval cooperation for sea-lane control and security. Indo-Iranian naval exercises such as the ones held in March 2003 and 2006 need to be resumed in future. Furthermore, bilateral naval exercises could also encompass anti-piracy operations and cooperation.20 As far as Army-to-Army cooperation is concerned, it could entail the following:

- Joint anti-terrorist exercises.

- Provision of course vacancies for Iranian officers at the National Defence College (NDC) and Defence Services Staff College (DSSC).

- Provision of training for UN peacekeeping operations.

- Training in English language and IT skills for Iranian armed forces personnel.

- Offer assistance in training as well as maintenance and repair of key Russian equipment like Kilo submarines and MiG-29 fighters.

- Maintenance and repair and training support for Iranian T-72 Tanks, BMP infantry carrier vehicles [BMP-I and BMP-II] and Russian origin artillery equipment (105 mm, 130 mm and 122 mm towed Artillery Field Guns).

- Provision of spares would be a major component of military ties.

- India could consider selling Advanced Light Helicopters (ALH) and jet trainer aircraft.

Despite these many forms of collaboration, more than a few constraints are likely to curtail the extent to which India might reach out to Iran in defence association. Assistance in these areas would be contingent upon scaling down of Irans hostility levels with the US and Israel. India receives major quantities of cutting edge equipment from Israel and as such cannot be seen as undermining its security by upgrading the perceived threat from Iran. New Delhis camaraderie with Iran especially in the field of defence collaboration incessantly carries a potential risk of putting it at odds with simultaneous improvement in ties with Israel and the US. The field of defence cooperation is subjected to close scrutiny and sensitivity as it comes under the scanner of the US and Israel.

Nevertheless, refuting to view international relations as a zero-sum game, Indias Ministry of External Affairs stated in January 2005: The United States has its relationship with Pakistan, which is separate from our own relationship with them”¦ Our relationship with Iran is peaceful and largely economic. We do not expect it to affect our continuing good relations with the United States.

Closer ties between New Delhi and Tehran especially in the realm of defence cooperation shall be of critical significance to both nations even as it might impact upon the West Asian politico-strategic dynamic.

During an April 2006 Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice was inquired about New Delhis relationship with Tehran. Of immediate interest to some Senators was an American press report on Iranian naval ships visiting Indias Kochi port for “training.” Indian officials downplayed the significance of the port visit, and Secretary Rice challenged the reports authenticity.21 Secretary Rice did however, sent a message across when she stated, “The US has made very clear to India that we have concerns about their relationship with Iran.”22 Furthermore, Israel has also raised concerns vis-Ã -vis New Delhis defence ties with Iran resting upon apprehension that India could divert Israeli military technology to Iran-a nation it describes as the “epicenter of terrorism.” During Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharons visit to India in September 2003, Sharon was reported to have demanded explicit guarantees from India that it would not transfer any technology acquired from Israel to any third country, especially Iran.23

Yet another episode that established Indias autonomous foreign policy approach came in March 2007 when Washington conducted its war games in the Persian Gulf-its largest show of force in the region since the 2003 intervention in Iraq involving USS Eisenhower and USS Stennis. This coincided with the visit of the Iranian Naval Chief to India-a reflection of the importance that Iran attached to its growing defence ties with India.24 Additionally, a naval cadet training ship visited India, and in 2007, the Indian government allowed a limited number of Iranian officers to participate in joint training courses with officers from several other countries.25

Conclusion

India will have to compete for influence in Iran and military-to-military ties would go a long way in cementing relations with Iran. Iran lies at the core of the worlds energy heartland formed by the Middle East and Central Asia. As such, enlightened self-interest demands that India should engage Iran in a constructive manner to safeguard its significant geopolitical and energy security stakes.

As of now, defence cooperation between the two countries appears low and patchy with ample scope for gaining momentum. Closer ties between New Delhi and Tehran especially in the realm of defence cooperation shall be of critical significance to both nations even as it might impact upon the West Asian politico-strategic dynamic. Despite the fact that resisting unvarying US pressure towards keeping its diplomatic and political channels open vis-Ã -vis Tehran, New Delhi should maintain an independent line while strategizing its foreign policy sans any threads binding the same. Thus, in a move that could radically alter the geopolitics of the region, Indian and Iranian defence cooperation could well prove to be an essential tool of foreign policy thereby strengthening mutual trust and enhancing security and stability in the region. It shall further be a significant pointer towards the emerging strategic calculations in the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea.

Notes

- For more on this subject see, Stephen Blank, “Central Asias Deepening East Asian Relations,” Analysis Biweekly Briefing, November 8, 2000.

- Subhash Kapila, “India-Saudi Arabia: The Strategic Significance of the New Delhi Declaration,” South Asia Analysis Group, Paper no. 1734, January 2006.

- Ministry of External Affairs, Annual Report 2005-06, New Delhi.

- Cited in K. Alan Kronstadt and Kenneth Katzman, “India-Iran Relations and US Interests,” Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report for Congress, August 2006, p. 4.

- Calabrese, “Indian-Iranian Relations in Transition”; “India-Iran Military Ties Growing,” Strategic Affairs, June 16, 2001.

- For more details see, Stephen Blank, “Indias Rising Profile in Central Asia,” Comparative Strategy, vol. 22, no. 2, April-June 2003, pp. 139-157.

- For more details see Joint Statement by the Republic of India and the Islamic Republic of Iran, “The New Delhi Declaration,” January 25, 2003, Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi.

- Donald L. Berlin, “India-Iran Relations: A Deepening Entente,” Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies Special Assessment, Honolulu, October 2004, p. 1.

- “Iran-India pact not a security concern-State Department official says,” Inside the Pentagon, February 13, 2003; also see, “India-Iran Military Ties Growing,” Strategic Affairs, June 16, 2001.

- Ibid.

- Ronak D. Desai & Xenia Dormandy, “India-Iran Relations: Key Security Implications,” Report by the Robert and Renée Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, April 2008.

- C. Christine Fair, “India and Iran: New Delhis Balancing Act,” The Washington Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 3, Summer 2007, p. 151; also see, House Committee on International Relations, The US-India Global Partnership, 109th Congress, Second Session, 2006.

- CRS Report, n. 4, p. 5.

- Berlin, n. 8.

- “India, Iran Cooperating on Space Research,” The Times of India, February 1, 2003; also see, Yiftah S. Shapir, “Irans Efforts to Conquer Space,” Strategic Assessments, vol. 8, no. 3, November 2005.

- Indian Ministry of External Affairs, Annual Report 2004-2005, New Delhi; also see, “Iran Sees Good Ties With India Despite India-US Nuclear Deal,” Agence France Presse, March 30, 2006.

- Rizvan Zeb, “Gwadar and Chabahar: Competition or Complimentarity,” Central Asia-Caucasus Institute Analyst, October 22, 2003.

- Monika Chansoria, GD Bakshi and Rahul Bhonsle, “Iran Analysis: A Net Assessment,” Project Study for the Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi, February 2009.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Vivek Raghuvanshi and Gopal Ratnam, “Indian Navy Trains Iranian Sailors,” Defence News, March 27, 2006.

- Transcript, “Senate Foreign Relations Committee Holds Hearing on US-India Atomic Energy Cooperation,” April 5, 2006.

- “Tel Aviv worried about New Delhis Ties with Iran,” The Times of India, September 11, 2003.

- Harsh V Pant, “A Fine Balance: India Walks a Tightrope between Iran and the United States,” Orbis, vol. 51, no. 3, Summer 2007, pp. 498-99.

- As cited in Teresita C Schaffer and Suzanne Fawzi, “India and Iran: Limited Partnership, High Stakes,” South Asia Monitor, Center for Strategic and International Studies, no. 114, December 2007, pp. 2-3.

Aciblefe http://paydayloanse.loan